Christine Haroutounian

«I’ve always had a desire to go from the unreal to the real»

Founder of the production company Mankazar – a platform to explore independent cinema in Armenia and beyond, filmmaker Christine Haroutounian works between Southern California and Armenia. Her work explores transnational life, ancestral inheritance, and darker layers of humanity.

Attending an Armenian school in Los Angeles’s San Fernando Valley, Harourounian didn’t head down the filmmaking path immediately, as she was first an art school student, then a photographer. Her time studying for an MFA in Directing/Production from the UCLA School of Theater, Film & Television was when she produced both her shorts ‘Fixed Water’ and ‘World’. They have received Official Selection in International Film Festival Rotterdam, Ann Arbor Film Festival, Palm Springs International ShortFest, and more. Mankazar is currently in development with Haroutounian’s first feature film, set in post-Soviet Armenia.

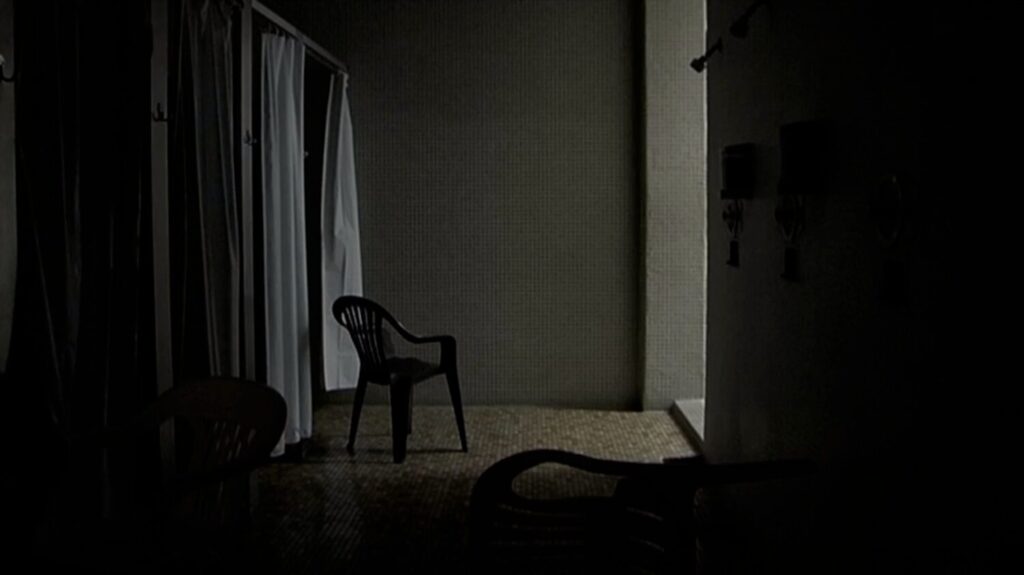

Haroutounian’s first short ‘Fixed Water’ follows the lives of an older Armenian mother and daughter who are seemingly the same yet worlds apart, delving into a difficult family dynamic. Like her first short, Haroutounian’s second film ‘World’ also explores a mother–daughter relationship, this time with a sharp and impolite rendering of end-of-life caretaking. Each film uses different textural approaches to impressionistic slow cinema.

NR Magazine speaks with Haroutounian to gain deeper insights into the cultural ties in her work and her attitude towards the concept of identity in her filmmaking process.

What inspired you to start your production company Mankazar Film?

My directing style is deeply intertwined with the production process, so it was only logical to start a production company. Mankazar is a filmmaking platform for a new Armenian cinema that works independently to the commercial film industry.

You have an MFA in Directing/Production from the UCLA School of Theatre, Film & Television – what did you learn about yourself during this time? Can you pinpoint a specific moment where you started to really shape your creative vision?

I learned all the rules of filmmaking but ultimately, no school can teach you how to look. In order to move away from a story,

«I realised my whole life had to become a work of art, and that starts with observing.»

You’re currently developing your first feature film set in post-Soviet Armenia. What has this process been like?

It’s been a complete act of faith. Psychic, scary, and ecstatic.

The film is titled ‘After Dreaming’ and is described as an odyssey of selfhood, drawing on the mythologies of freedom, family, and motherland. How have these concepts shaped your identity as a filmmaker?

I would say that it has shaped my identity as a filmmaker as throughout my life I’ve always had a desire to go from the unreal to the real.

What has resonated with you the most from working across Los Angeles and Armenia?

I feel spiritually vacant in Los Angeles and very aligned in Armenia. The latter is largely viewed as a corrupt place, where there is no stability or future but plenty of romanticism. I feel like people are deceived into thinking Los Angeles is somehow none of these things. It’s fascinating what stories and projections we choose to believe over others.

‘World’, your second short film, is a sharp and visceral take on end-of-life caretaking, and you’ve mentioned that it questions how one should behave as a caretaker and a daughter in the presence of fear and death. Are these things you’ve had to navigate in your own life? Does this presence of fear ever restrict your creative process?

The film is fiction, but I do grapple with fear and attachment because I love life very hard.

«If fear gets in the way of my creative process, it’s usually because my brain is asking the wrong questions.»

Your first short film ‘Fixed Water’ also explores a mother-daughter relationship and intergenerational tensions. Does the filmmaking process ever take on a cathartic role for you?

I don’t use filmmaking as a psychological exercise, but it is cathartic in that I focus large amounts of energy into something that doesn’t exist until it materialises the exact way I envision it.

What was it like growing up in Los Angeles’s San Fernando Valley?

I always felt that there had been some kind of terrible mistake for me growing up in Los Angeles.

What things help to develop your filmic voice?

Knowing in my heart that cinema is a gift.

You mentioned that Andrei Tarkovsky’s ‘The Mirror’ and Chen Kaige’s ‘Yellow Earth’ were among the films to make an early impact on you. Could you talk a bit about the specifics of these inspirations?

I am almost an amnesiac when it comes to films and mainly just remember the physical feeling I’m left with. I recall feeling crushed by the landscapes and weightless through the rhythm of time, and also how real the classical elements felt through such simplicity. I should probably rewatch these soon.

What would you say your ambitions as a filmmaker are?

Total freedom!

You’ve described your background as being of a very particular ancestral inheritance, and that being exposed to the darker layers of humanity from a very young age has made you very sensitive to the human condition. Could you talk a bit more about this?

To learn Armenian history and to look at the present, are in many ways a collision with the abject. I don’t have the option to unsee these crude existential realities, and some days, it engulfs everything I do. It’s a forced awareness of what people are capable of, for better or worse.

With the theme of this issue being Identity, I’d love to know your thoughts on how you feel you explore your own identity with your work.

I follow my intuition more than any intellectual concept, and I can’t work from a preconceived agenda. Even if I’m going through something or making work that is informed by my cultural ties, I never experience it as ‘identity’. Nobody processes life this directly. It’s inherent. Simply being is more specific and universal than any one identity.

Where do you see your practice heading?

Making more films!

Credits

Images · CHRISTINE HAROUTOUNIAN

www.mankazar.com