Joshua Gordon

The underbelly of alt culture

When Joshua Gordon went to Thailand, he followed a gang of teenage bikers and witnessed their fraternity. He saw how the young boys had each other’s backs and would die for one another. He directed the film about this along with the country’s occultism and witchcraft culture that religious people might completely exile in their belief systems, but that other people base their spirituality and faith on. After a while, he wanted to investigate the drag landscape in Cuba. Armed with his lens, he was hoping to capture the tight-knit drag community in a country that might not yet be open to the queer scene. He ended up meeting twin trans sisters and peered into their intimate life.

Joshua’s thirst for fascination also brought him to Japan. Amidst the psychedelic allure and eccentricity of the country, he photographed the locals’ fascination with toys. He saw young punks living and sleeping with their plushies, a lifelike woman giving birth with the baby’s head popping out of her vagina, and lots of latex sex dolls in stores and homes. Somehow, Joshua knows how to excavate the surface of the social infrastructure. He digs hard and deep that midway, his photographs and documentaries have unraveled parts of him that seem to be hidden in plain sight. These visual cues are snippets of the ups and downs he has gone through in life and art, a narrow gateway to who he is and how he became what he is.

Take ‘Transformation,’ where he manipulates photos of himself using artificial intelligence to bring about different versions of himself. He considers the project special to him, but viewers seem to have only noticed and commented about his physique and the size of his penis. The series has become reduced to a visual commodity for public viewing, making Joshua aware and alert to the current relationship between art and the viewers. What Joshua creates gives nothing in-between; either the viewer gets startled by the brashness of his images and films, or they feel for the emotions the visual works evoke. Every publication and project hides a backstory, and in a conversation with NR, Joshua brings them to light.

Matthew Burgos: How did you develop your documentary style in photography, video, and collage? Has this always been your intended style?

Joshua Gordon: Documenting was always the first thing I did. I started using photos as a tool when I began creating pictures at around 13/14 years old, not for any artistic reason or self-expression. Every skate crew needed a filmer and/or photographer, so that’s what I became. And every graffiti crew needed someone with a camera, so I filled that role too. Over time, through graffiti, I learned more about photography and discovered my favorite photographers. After that, I delved more into what might be considered quite traditional documentary photography.

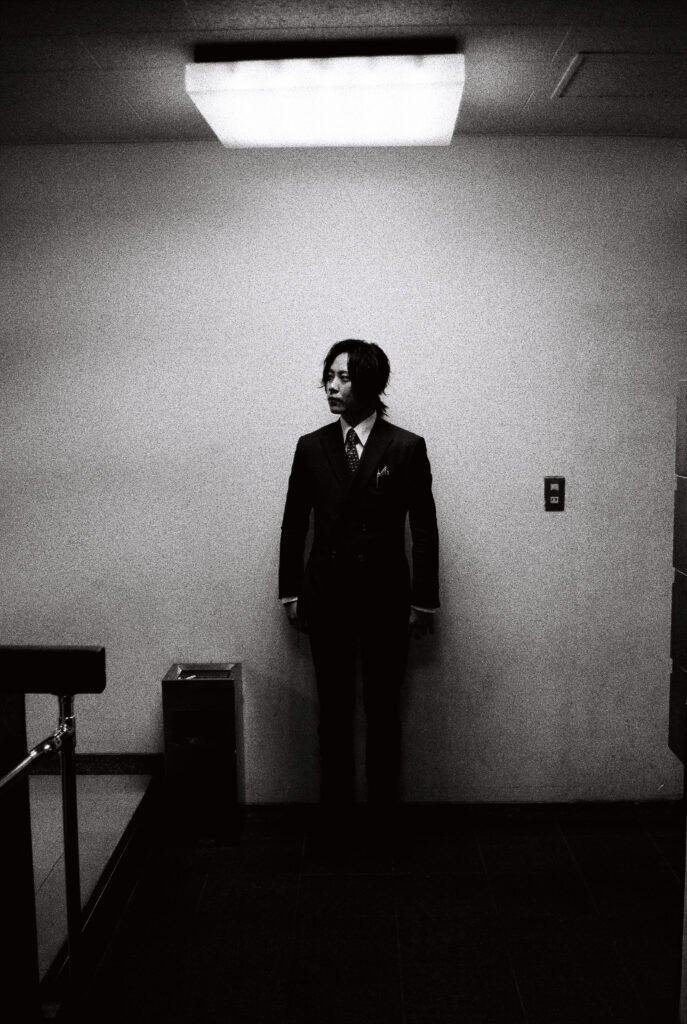

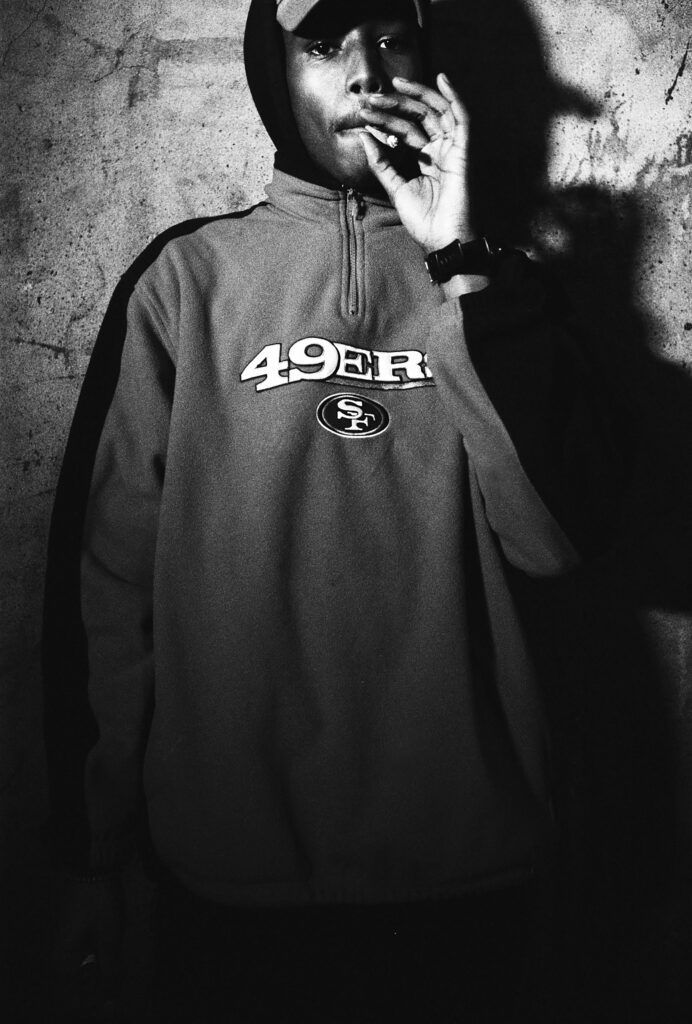

Matthew Burgos: Let’s discuss your zines Diary Part 1 and 1.5 which definitely have the documentary photography style you just mentioned. Do you see the photos in these zines as a reflection of how you saw and painted the world at the time, with the use of dark and gritty imagery?

Joshua Gordon: I think it’s dark and gritty because I was depressed and poor at the time. I was living hand to mouth and didn’t really have a penny to my name. When Diary Part 1 was made, I was working in a warehouse loading trucks and stealing stuff from high-end stores for cash. The other zine was created just after I left.

I think that when I started making pictures for those books, I wanted to shock and be brash. I was surrounded by a lot of misery, staying in moldy bedsits with rats crawling on my ceiling, and I was never able to pay my rent. Shocking isn’t my intention now; I’m more interested in evoking emotions.

Matthew Burgos: Your Butterfly project seems to have a similar style yet a different tone. Can you talk about how you approached this project, and what brought you to explore the nightlife in Havana?

Joshua Gordon: Well, I don’t really plan much; I just go with the flow and feel things out. I’ve always been inspired by 80’s drag, and it’s been a constant source of inspiration for me. I wanted to find some older drag queens and live with them.

Aries offered me the chance to go to Cuba and work on a project of my choice, including creating a book. I was going there to explore and see what I could find. When we arrived, the queer world was small and super intertwined. It ended up being less about drag and more about these two twin sisters I met and their friends. I suppose you could say it was a portrait of them and their community.

Matthew Burgos: You also directed Krahang, following a group of teenage biker gang in Thailand. How did you discover them, and what did you learn about them that wasn’t evident in the film?

Joshua Gordon: There are a lot of interesting things happening in Thailand—hidden customs and alternative perceptions towards topics that might be considered taboo in other parts of the world. What sticks out to me when I spend time in Southeast Asia is the sense of community. The West is obsessed with individualism. Everyone thinks that the world revolves around them and people have the “main character syndrome.” There’s no decency or love among people.

In Thailand, life is hard and fast and vibrant. There’s a strong community spirit. The boys in the gang were best friends and would have died for each other. I was also very interested in Thai witchcraft and occultism, which is something pretty much everyone there is interested in or scared of. I touched on that in the film along with the teen biker gang.

Matthew Burgos: Let’s talk about your investigation into adult toy culture in Japan leading to the book TOY. What specifically drew you to explore this topic in a country known for its eccentric culture?

Joshua Gordon: I love toys; they’ve been important to me my whole life. Objects bring me a sense of comfort and fluffy familiarity when I travel. Everything in Japan is “kawaii:” you see an ambulance speeding down the street and its logo is a smiling drop of blood. Even the police logo Pipo-kun is fucking adorable. Japan is cute but it also has a dark edge. I wanted to show that mix in the book; the duality of cuteness and darkness.

During my time in the Japanese countryside, in a quaint area called Gunma, I found an old toy museum. Inside, I discovered these porcelain sculptures of couples with long robes on. When you turn them upside down, you see the characters’ penises and vaginas with fuzzy pubic hair. A lot of things in Tokyo have a hidden meaning or a secret backside; I wanted to explore that.

Matthew Burgos: How about ‘Transformation’? Is it a visual anthology of the growth you’ve experienced throughout your career?

Joshua Gordon: I was at my lowest when making ‘Transformation.’ I was dealing with a severe eating disorder, hospitalization due to tumors, a difficult breakup, and substance abuse, and I felt like I was going insane on a little beach in Mexico. The photos helped me escape somewhere else. I tried to use artificial intelligence and children’s image manipulation apps to create a fantasy land of my own.

But nobody understood. I received comments about my physique and penis size—just basic interpretations of something that meant a lot to me, a project that acted as sort of a ladder to help me out of my hole. It was devastating. I spent around 7,000 pounds and six months creating the books and artworks. I managed to sell only one book at the exhibition and not a single painting. It was quite upsetting, but the project (still) means a lot to me.