Valie Export

«The most important issue for me is: how can we live together peacefully?»

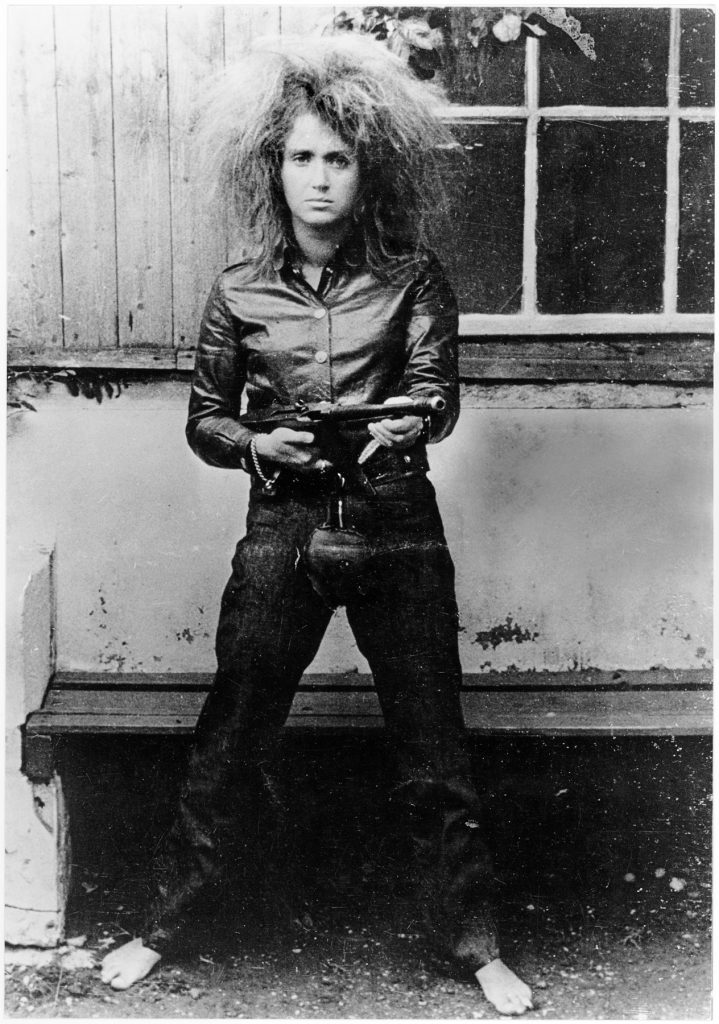

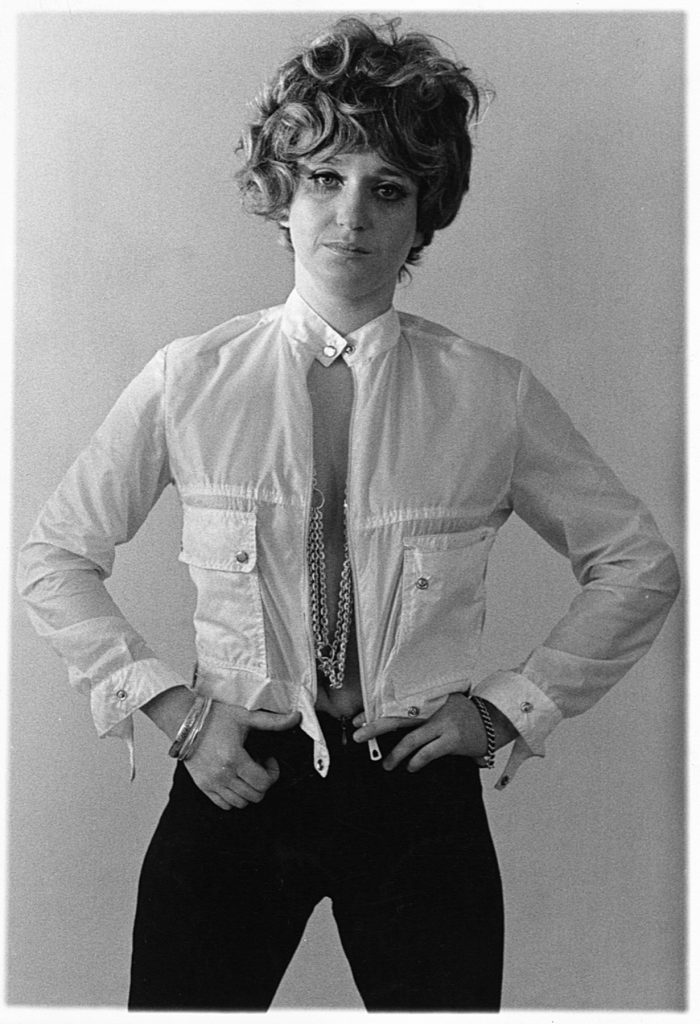

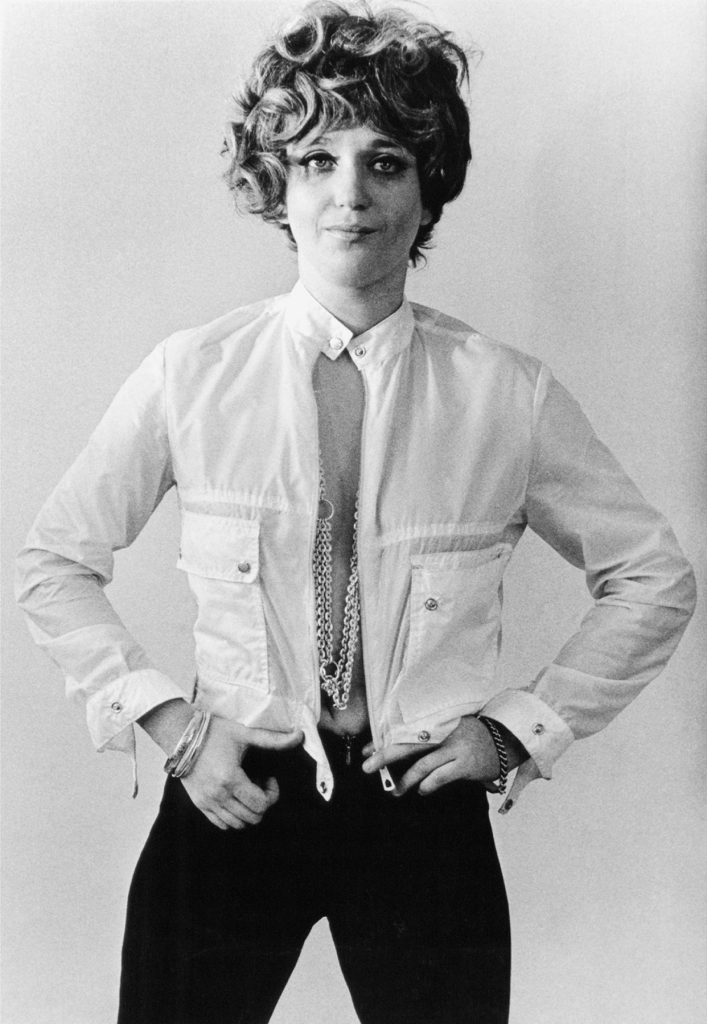

In 1968, the artist VALIE EXPORT walked into a porn film screening at a cinema in Munich, wielding a machine gun and wearing crotchless pants. Forcing the gaze of cinemagoers to meet her bare crotch, VALIE EXPORT sought to demonstrate that women, in film, were merely passive agents – look instead, she demanded, at a real woman, not a depiction of how they are shown to be seen. But only part of that story is true; it wasn’t a porn film screening, and the artist did not have a machine gun. Nonetheless, the tale of VALIE EXPORT’s action has entered the domain of art legend. Part of the myth that surrounds what really happened can be attributed to a series the artist created the following year. In Aktionshose: Genitalpanik (Action Pants: Genital Panic, 1969), VALIE EXPORT is photographed wearing those crotchless pants, her legs wide, as she holds a machine gun across her chest. But if, by entering the cinema in Munich, VALIE EXPORT forced the viewer to confront a ‘real woman’, the Aktionshose series is less clear-cut. Here, the artist adopts a macho abrasiveness – such is the power of a staged photograph to manipulate how gender and identity are represented and viewed. By contrast, the triptych Identitätstransfer (Identity Transfer, 1968) takes a nuanced approach to explore a similar theme. Across three portraits, the artist subtly adapts the way she poses, how her clothing hangs, and the expression on her face. Who’s to say which is more feminine, and which is more masculine?

Part of the Vienna Actionists art group in the 1960s, VALIE EXPORT was an early adopter of using film to confront and subvert representations of gender and identity. As VALIE EXPORT tells NR, Aktionshose is part of her expanded cinema practice, in which the traditional boundaries of film are subverted, and the viewer (unwittingly at times) plays an active role. This is perhaps most obvious with Tapp und Tastkino (Tap and Touch Cinema, 1968) which saw VALIE EXPORT invite members of the public to put their hands in a curtained box, shaped like a television or the stage of a theatre, that the artist wore across her chest. Inside the box, VALIE EXPORT’s, mostly male, participants were able to touch her bare breasts for 33 seconds, whilst directly confronted with the artist’s face in close proximity. It’s impossible to underplay VALIE EXPORT’s contributions to feminist art practice – even down to her name itself. The artist changed her name to VALIE EXPORT in 1967, in reference to both a childhood nickname and a brand of cigarettes, thus removing the patriarchal connotations that her former name (her father’s surname, and later, her husband’s surname) had. In this way, VALIE EXPORT’s work is a negotiation, nay confrontation, of the patriarchal ways through which a woman’s experience is constructed.

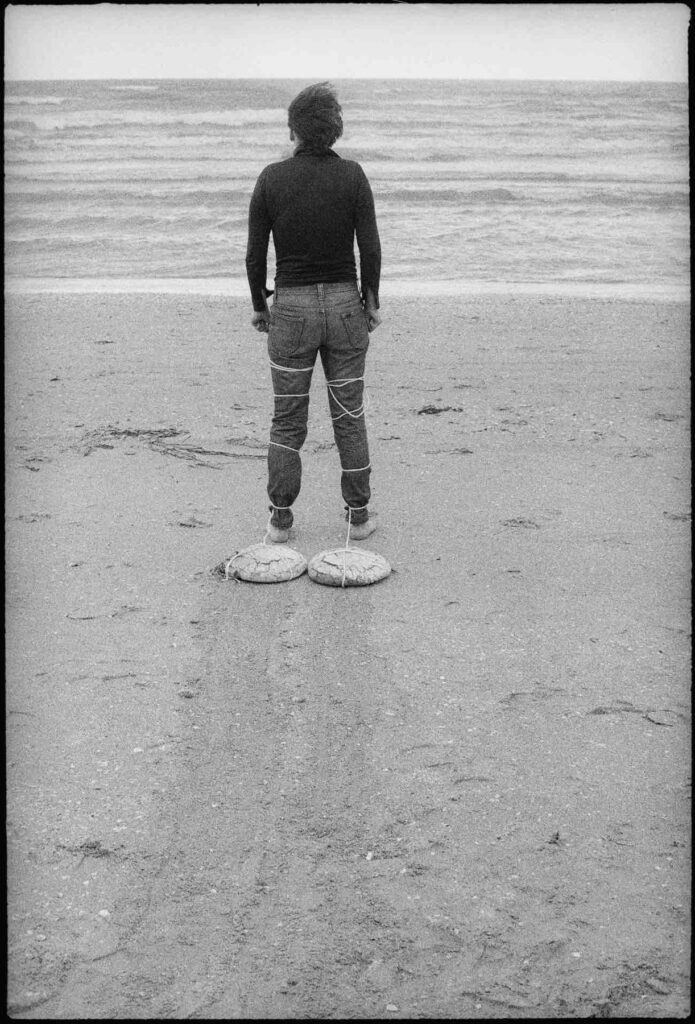

Crucial to this, is the artist’s navigation of space. VALIE EXPORT’s early work came at a time when Austrian society was still deeply conservative. In the series Body Configurations from the 1970s, for example, the artist is photographed contorting and morphing her body to complement the built environment of Vienna. Yet no matter how far VALIE EXPORT adapts her body in sculptural ways, she remains unable to fully replicate the cold, patriarchal surfaces of her architectural surroundings. The series is, nonetheless, a reclamation of space – as is the fact that the screenprints of the Aktionshose series were pasted up in public spaces around the city. Whilst the artist has adapted to using new video technologies over time, and broadened the themes she explores (such as politics and violence), the impact of VALIE EXPORT’s early work, radical as it was at the time, remains important today.

NR: Aktionshose: Genitalpanik and the legendary story about the original action, remain hugely influential; did you anticipate the impact that it would have?

VE: Of course I expected it to have some effect, but not that it would have this kind of impact. Aktionshose: Genitalpanik is an ‘Expanded Cinema’ practice, which was screened for the first time in a Munich art cinema. In this action, I walked through the rows of the theatre wearing the Action Pants. The audience left the theatre, and it emptied quickly. Afterwards, I used the same pants to create a self-staged photo series in and in front of an abandoned movie theatre and made the poster, which has become quite well known. I tried for years to exhibit the photo series and/or the poster, but unfortunately people refused to show them. I only succeeded in exhibiting the works very late in my life.

Do you think an audience’s reaction to your work varies depending on the time period in which they engage with it? Have people’s reactions to your work changed over time?

I have difficulty assessing whether people’s reactions to my work have changed over time.

«I think that the reactions are just as strong today as they were back in the day but might go in a different direction.»

Today, my works are also documents of a time of artistic and political awakening, and represent the breaking away from prevailing rules and opinions that are prescribed by society. With my artistic expression, I try to portray socio-political and cultural-political oppressions and norms through art-political processes and to sharpen the perceptions we have of them.

Have your own reactions/feelings towards your work changed over time? If so, how and why?

My own reactions and sensibilities have not changed. I always perceive my works in the context of the respective time in which they were created.

«I create my artistic expression with a view on the present period of time – and maybe also with a gaze to the future.»

You’ve spoken previously about how your art was made in reaction to the society and culture that it was contemporary to – how much of that moment in time has changed, and how much has remained the same?

I don’t think a lot has changed fundamentally. It requires a vigorous process of awareness to perceive change and to recognise the repetitive. Often the same things are only embedded in a different context.

How has your practice changed over time and have the initial demands of your work given way to new concerns?

The passing of time gives rise to new concerns. But these concerns also always seem to have a common thread.

From your perspective, what conversations should artists be having now – and through which mediums should these be communicated?

I believe conversations should be had about every possible issue and communicated through all kinds of mediums.

«The most important issue for me is: how can we live together peacefully?»

The theme of the magazine’s issue is ‘celebration’; what would you celebrate in relation to the impact that your work has had on the themes you sought to explore/counter?

Oh, I could think of many rituals that would lead to a celebration – but they are mostly determined by rules. I wish for a free celebration.

When you came up with the name VALIE EXPORT, which you stamped on your work and as an identity through which to communicate meaning, did you consider that you were creating yourself as a brand?

I didn’t invent VALIE EXPORT as an alter ego but a trademark. As a trademark with which I export my thoughts, through which I export my ideas, weave them into dynamic networks. For some years now, VALIE EXPORT has become a trademark: VALIE EXPORT®. This is how it should always be spelled, but the capitalisation is mostly ignored. The trademark is an advertisement for VALIE EXPORT rather than myself.

Credits

Images · Valie Export

https://www.valieexport.at/