Deadhungry

“I think you can get so stuck in trying to sell something, that you forget you can have fun and play around with it”

Chef and photographer Alex Paganelli has carved himself a unique position in the industry, operating with ease across the realms of food styling, film direction, menu designing and product development. Uniting the culinary, art and fashion worlds, Paganelli injects a vibrant energy into his creations, and has established himself as one to watch, having already worked on campaigns for brands like Skims and Bottega Veneta – but this is only one level of his flourishing food empire.

Growing up in the French Alps, Paganelli picked up his interest in French cuisine and cultural diversity, which came natural with Italian-British parents. Moving to London at 18, Paganelli took the techniques he learned from home with him to the kitchen and discovered a yearning for a creative process detached from tradition, and began shaping his own signature style, creating things that were stunning to behold, but also wonderful to eat.

Since establishing DeadHungry in 2015 – a studio, kitchen and creative hub for his food ideas, Paganelli has catered for specially-curated events and has built a strong reputation for daring menu design and serving eclectic, modern and experimental dishes.

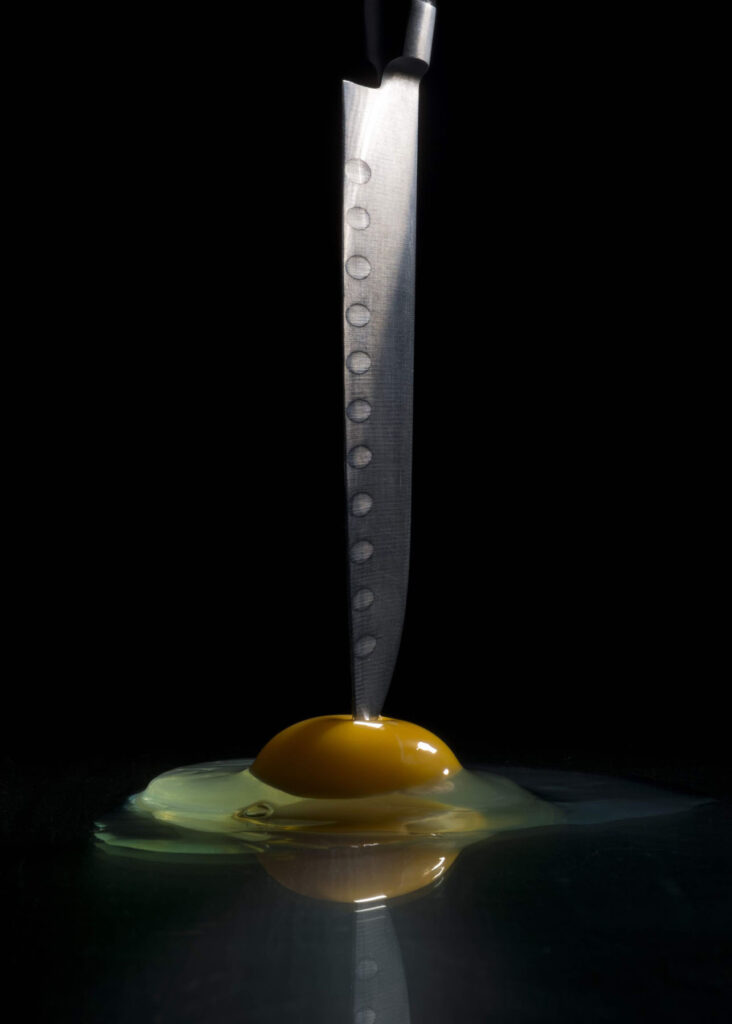

Paganelli continues to subvert the conventions of food photography and conjures up scenes and dishes that are optical feasts, including life-size jelly shoes and handbags, cartoonish pies and mind-bendingly visceral table settings.

NR Magazine touches base with Paganelli in London to learn more about his visual language and creative evolution.

Growing up in France – a culinary capital of the world, how did this influence you when you first started as a chef?

France influenced me a lot. I grew up there and I lived there until I was 18. My mum is from London, so I used to come and spend my summers here with my family. My dad is from Italy, but the whole family moved to France when I was a child and we used to live close to them. They were a typical southern Italian family, so I think I’ve been influenced by all three if that makes sense- my dad’s Italian family, my mum’s British family, and then of course me growing up in France. I think all three really had an impact on my work, what I cook with and what I like to eat.

I grew up more or less with a Mediterranean diet, but then moving to London I discovered so many different types of cuisine. I met and worked with people and chefs from all over the world, so later in life I realised that even if I’m drawn to more traditional food, London has added an element of modern cooking, in a way that I don’t think I experienced growing up in France.

When did you start to shape your own signature style?

It was something that happened over time. I think my style grew after I became a photographer, but that happened a little bit later. At the beginning of my career, I was just focussing on food, but then I started documenting my work and eventually started getting hired as a photographer. Eventually it all melded together and formed what is today my style. It took a little while though. At the start, when I was only working with food and wasn’t really photographing as much, I hadn’t really figured out what my style was, and I didn’t really understand fully what it was that I was trying to do.

Eventually I started using different techniques, like I stopped using animal products and started to create more vegan dishes. That defined it a lot more, and I think that’s what made me grow in a way that was quite unexpected. Up until then I was cooking in a more traditional way, using very traditional ingredients, and when I decided I was going to use more plant-based ingredients, I realised there weren’t really any rules for that because it’s such a new way of cooking. I think that’s what really influenced the way that I cook. I realised that it was this exciting, new territory, where I didn’t have to stick to such a specific and traditional way of doing things. I think that’s when I realised my career was starting to grow in a different direction.

Are you vegan yourself then, or is that just what you happen to cook?

I cook and eat more or less the same stuff. There are a lot of chefs that will cook very differently to how they eat at home, but for me it’s more about blending it together. I don’t really believe in cooking something that I wouldn’t want to eat myself. In London I would consider myself mostly vegan, but if I’m in a place somewhere in the world where it makes sense to eat a certain food, then I can easily be influenced by those local ingredients – I have no problem doing that. I was in Nice for quite a while, and I did eat quite a bit of fish there.

For me, it’s more about blending into the environment you’re in and eating what makes sense in that location.

Yeah, that makes sense. I’ve got a lot of family in Greece, and obviously their cuisine is based a lot around things like cheese and fish, so when you travel there, it’s hard not to eat those things.

Exactly, and I also think the quality is and important part of it. I think eating a packaged piece of cheese from the supermarket is different to eating some that has been made on a really amazing farm. It’s part of the culture there which makes a big difference.

What inspired you to create DeadHungry in 2015?

I’d been working in restaurants for quite a few years, and I realised that the restaurant pace was quite draining. I couldn’t see myself doing that full time for the rest of my life. There was an aspect of photography that I’ve always loved, which started off as a hobby rather than a career. But from the beginning I decided I was going to pursue a career in food and with that and I knew there was an element of creating visuals that I was really drawn to.

I really love creating imagery with cooking, so I found a way of blending the two together. But I never thought I was going to become a photographer – it was never a goal, it just happened.

Your work explores the different textural potential of food and objects, and your film direction, particularly with Bottega Veneta employs similar aesthetics and sensory techniques to ASMR videos. Do you draw inspiration from things like that? It seems like exploring different colours and forms is a key part of your work.

I’m not specifically influenced by things like ASMR. I would say it’s more a case of me liking anything detail oriented. I like anything that focusses on a great depth of colours and textures in general, and I think that’s something that we don’t really see much in food photography, apart from real close-ups of food that I think feel quite commercial.

I was always interested in things that were odd and almost a little bit repulsive. That part of food photography is something that I don’t think a lot of food photographers touch on. That’s become my point of view over time. It’s more about photographing things that we’re not used to seeing, for example I love to photograph things that are rotting, but as a food photographer, that’s not really something that you’re going to focus on, but it’s something that I personally find really visually appealing.

Your work has a very playful feel to it and at times, a darker sense of humour that shows off a different side to food photography. What inspires you to combine the worlds of gastronomy with art and fashion in this way?

Again, that wasn’t something that I specifically thought I wanted to do. Those were just the type of clients that started coming my way, and I realised I had to adapt my work to fit the fashion world and its products in that way.

I think I’m inspired more by fashion photographers than food photographers – like more art photographers and still life photographers. That’s where my references come from. It wasn’t a conscious effort of combining the worlds of food and fashion, but over time, working with a lot of fashion brands and clients, it evolved into that.

I also noticed that some of your photographs are reminiscent of classic still lifes, but with a modern twist. Some of your tables are set in the style of the 60s and 70s, and have a nostalgic feel to them, particularly with the colourful jellies. Do you draw much inspiration from these eras?

I think I’m inspired by those eras for sure. It’s embedded into my work somehow. It’s not necessarily something I’m specifically drawn to, but there’s definitely a nostalgic feel to what I do.

I’m just attracted to anything beautiful, and perhaps a little romantic at times. I think that’s just a product of my taste.

What’s your usual working process – how do you approach developing new ideas?

I approach new ideas in lots of different ways, it just depends on what I’m doing. If I’m thinking of a photoshoot, then it’s more about understanding the product. If I’m working with a brand, I try to understand what their idea is and how I can then integrate that into what I do.

If I’m testing and developing a new dish or certain flavours, then it starts with a couple of ingredients that I want to work with – usually something seasonal that’s just become available. In that case, it’s more a matter of just testing it in my kitchen until I have something that I like.

I follow quite simple guidelines with the way that I shoot – I’m either shooting a beautiful dish as it is, or I photograph the process of it, as sometimes that looks even better than the final product. There are certain things I’ll make that are delicious to eat but that might not necessarily look very good on camera.

In terms of pure photography when it doesn’t have anything to do with a really tasty dish, then it’s more about getting the right elements in the studio on that day and getting my team to do the things they are good at, and honestly just having fun and not overthinking too much.

I think the best ideas come when you have a solid idea in your head, you don’t overthink every shot and you just have an overall idea of what the mood is going to be. The rest just falls into place.

What artists and chefs inspire you at the moment?

There are some pastry chefs that I love like Cédric Grolet in Paris. He’s very famous now but I’ve been following him for quite a while. There’s also this amazing artist called Craig Boagey that I discovered who does these incredible paintings of mushrooms but I’m also a huge fan of Sam Youkilis who does lots of moving images of mountains and stunning landscapes (amongst other things including lots of food) which remind me of home. Things come and go. I get really obsessed with people over a few weeks or a few months at a time and then I’ll move on to something else.

Do you feel like your identity as a chef and as a creative is rooted more in France or London?

I’ve lived in London my whole adult life, so I think everything that I’ve ever created with DeadHungry has been created here, so I’d say that my work is deeply rooted here. In terms of my inspiration, that definitely comes from other places. I grew up in the Alps and spent most of my childhood there, so that’s a very special place for me. Every time I go back, I feel really inspired.

It’s funny though, because I eat very differently when I’m there compared to how I eat here, and I think of food in a completely different way. I think London has this immense pressure – there’s this stress to deliver things that are exciting and different all the time, whereas in other places you don’t think of it like that. Instead, you think of food more as a necessity rather than an artform. I think they’re both very important and they’re both part of how I work. They’re two very different approaches but I don’t think I could do what I do without them both.

What do you find most interesting about the intersections of the culinary and fashion worlds?

When you work for a food client that wants to sell a product and wants to focus on what that food is for a restaurant or a hotel etc, I think you can get so stuck in trying to sell something, that you forget you can have fun and play around with it. What I really love about shooting food for a fashion brand is that it doesn’t really matter what the food is, as long as the overall image looks good or has an energy or an emotion attached to it that is interesting and visually appealing.

If you were just focussing on food clients, all you really want to do is make something look delicious, and that’s not always the best way of taking an amazing image. Sometimes trying to be too realistic takes away from the magic of creating an image. That’s what I really like doing with brands that aren’t necessarily always about food – you can have more fun with them without having to worry about what every element looks like. As soon as you start to do that you lose the sense of a really interesting image, and it just becomes more about the product.

With the theme of this issue being Identity, I thought it would be interesting to hear about your signature dishes or any favourite recipes from your childhood.

Honestly, the thing I love to cook the most is pizza. I know it sounds really basic, but it’s what I love to make the most. It’s so simple and it’s something that everyone loves, but its also something that is a lot more difficult than people think – it took me years to perfect a really good dough.

I also love pastries, and I love to cook with seaweed. I don’t really have a specific recipe that I go back to, but there are certain kinds of food that I seem to always go back to, and then maybe new flavour combinations will come out of that.

I’m really into cooking vegetable skewers at the moment, but things come and go depending on the season. Since I’ve been vegan, I find the versatility of an ingredient like seaweed to be really interesting.

What stands out to you most about the London food scene?

The level of the food industry is really high in London. When I go back to places like France, people always ask me ‘don’t you miss French food and French ingredients?’ and in Italy it’s the same. People say the food is disgusting in London, but I’ve had some of the best food in the world here. There are so many people from all over the world, and so many different communities – you can go east and see the Vietnamese community, you can go a little bit more north and see the Caribbean community, and every community has some stand out places that are incredible.

Something I miss when I go away is that idea that I can have food from all over the world. If you know where you’re going, you can find things that are incredibly special, and I love that.

The downsides are that it’s a very fast-paced city, and a lot of restaurants open and close really quickly, because its very expensive and its not necessarily financially viable to run a restaurant. I think in general, it’s a very hard city to break into. The food industry is one of the most difficult industries to get into. It’s very challenging to own a restaurant and I admire people who can actually run a restaurant 24/7, because it’s so demanding and such hard work. But I think it’s also a very special place for food.

I love it. It’s so diverse, and we have some of the best chefs in the world here. So many chefs come through London just to open a restaurant because they know the clientele is here.

Do you think you would ever live anywhere else?

That’s the question I’m asking myself! I’ve been here for 14 years, and I love it, it’s an exciting city, but I think the older I get, the more I realise I’m ready to live a life that’s a little bit more relaxed.

I think as long as I have a foot in London then that’s fine. I’d still want to be in the city, because it’s an exciting place to be, and I think you learn so much from other people here and get so easily inspired. I don’t think the level of creativity would be the same in a smaller city, and I think I would miss that if I left. But I’m definitely drawn to a more relaxed lifestyle with a bit of sun.

Is sustainability important to you and your work?

Yes, its really important! It wasn’t something I thought was that important when I started working, but now I think every chef in the world has some level of responsibility and should understand that we can’t really be cooking in the same way that we were 50 years ago. I think if we want to move to a more sustainable food chain in general, and we want to really improve our systems, whether that’s the way we farm and fish or the way that we eat – I think it’s a collective effort.

I think chefs have a responsibility to show people options and to make good examples. I take it quite seriously, that’s why I don’t cook with meat and fish anymore. Especially in a big city, you hear lots of people say, ‘what if we all bought meat and fish from sustainable farms?’ and that’s great if you have the money to do that. I don’t disagree with the idea that we should still be eating meat every once in a while, I just don’t think it should be part of our diets in the way that it is now – I think it should be something we do extremely rarely.

The problem is that it’s cheaper to buy a kilo of chicken wings in a supermarket than it is to buy really good quality vegetables. I think that’s where the responsibility for chefs lies, in breaking away from that broken system.

How would you define your visual language?

It’s quite dynamic and has a touch of camp to it. There’s something very raw and vibrant to it as well. The idea of photographing things that are very realistic doesn’t appeal to me. I like things that are a bit surreal. That’s what’s fun with photography – being able to replicate something that you don’t always see with your own eyes. I don’t understand the point of photographing things the way that you see them in real life. Why not have fun with it?

There are amazing photographers that do documentary and journalistic work. Some people are very good at that, but for me, it’s more about being able to capture something that is a little bit surreal.

What’s been the most daring or challenging thing you’ve done in your career so far?

I think generally, opening the studio a couple of years ago – that was very challenging. So far, it’s been trying to establish myself as a chef and a photographer on the same level. That was something that before I had the studio, I was really struggling to do, and my career was moving more towards creating imagery and less towards cooking, so being able to establish that has been very important. It has been challenging but also very rewarding, because I realised how important they both are, and how I couldn’t really be doing one without the other.

I think the most challenging things are yet to come. I’m looking at opening a new studio – something a bit more stable and solid, that could be running a more regularly than what I’m doing now. At the moment my studio is here, but I only open it every once in a while for dinners, so I’m looking to open something that could be a bit more permanent.