Jessamyn Lovell

“we can find power in the choice to engage in public sousveillance (surveillance of ourselves) but it also gives power away”

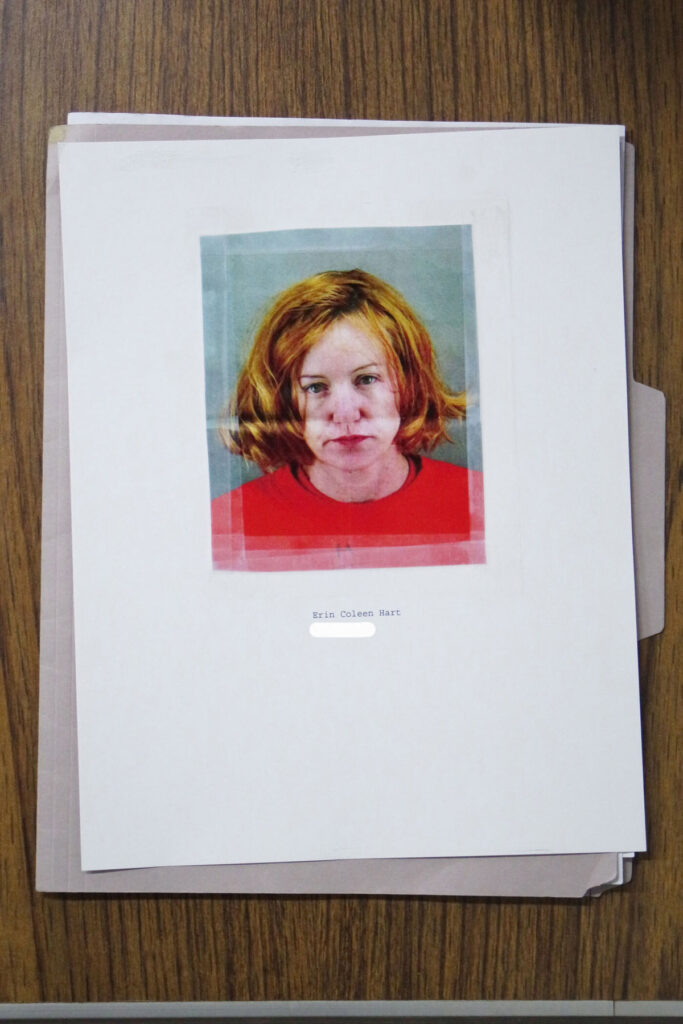

A wallet is stolen from a gallery in San Fransisco, just over a year later a woman receives a summons to appear in court for a petty crime she did not commit. It sounds like the beginning of a movie but for artist Jessamyn Lovell it was reality. She learned that her identity had been stolen by a woman named Erin Hart, who had been using her name to check into hotels, hire cars and to shoplift. As a way to help deal with the trauma of the situation, Lovell began the Dear Erin Hart project where she documented the process of tracking down and surveilling the woman who had stolen her identity.

Unable to find Erin Hart on her own Lovell hired a private detective and soon discovered that Hart was already in jail for a previous misdemeanour. However, upon Hart’s release Lovell and the P.I she had hired followed Hart around the city, photographing her. Lovell decided against contacting Hart directly and instead wrote the other woman a letter explaining the project to her. No reply was ever received. While Dear Erin Hart is perhaps Lovell’s most known work she is no stranger to documenting the lives of herself and others and it forms a central part of her practice. NR Magazine joined the artist in conversation.

What does Identity mean to you as an artist?

I have often used my artistic practice as a way to research and hopefully come closer to understanding the different and fluid aspects of who I am in relation to others. Throughout my life, I have assumed and shed many different identities, which have brought waves of immeasurable grief as well as limitless joy. I see my job as an artist to explore and reflect on these observations and discoveries to those that might see my findings as interesting and/or useful.

Do you think surveillance has become an integral and practically unnoticeable part of our lives given the rise of social media and apps having access to our phones at all times? How do you think this will affect us in the future?

I cannot really speak for other people’s experiences navigating public and private spaces but I certainly notice the mechanisms of oppression in every surveillance camera and security guard watching me. I have come to understand surveillance to be part of my everyday experience while doing what I can to avoid it. I see it as a gaze of sorts coming from systems of oppression. I think we can find power in the choice to engage in public sousveillance (surveillance of ourselves) but it also gives power away, especially for more vulnerable populations like young people who may not be as aware of the implications and lasting impact willingly sharing information might have. As a private investigator, social media is an important research tool in the work I do. As I have learned more and more about how much and what types of information you can learn about people online;

“I have personally pulled away from engaging in sousveillance on social media, which has compelled me to find other ways to artistically process my experiences.”

I think privacy is very rare these days and I only see that becoming more and more the case.

Can you tell me more about your work ‘No Trespassing’ where you documented your estranged father?

The gist of this project was that from 2007-2010 I found, followed and photographed my estranged father as a way to sort out if I could ever reach out to him or be in his life again.

“My father tried to have me kidnapped when I was a little girl after he left our family. I was estranged from him for most of my life by my own choice after that.”

I started following him initially as a way to take my own power back using the long lens of my camera. As the project progressed, I started to see my acts of surveillance as a private performance just for me. I came away learning more about my own identity apart from him as well as the ways in which the abuse I suffered at his hands had, in part, informed who I had become as an adult. I documented the process and shared it as a book and exhibition as a way to interrogate the spaces between fact and fiction in our own histories as well as in storytelling.

You obtained a Private Investigator licence, what are the requirements to gain this license and now that you have it what is the legal extent of what you are able to do when surveilling an individual/s?

In the United States, the license needed to legally practice as a Private Investigator is state by state but the requirements are all pretty similar. In New Mexico, where I live and work, 6,000 hours of investigative work are required as well as passing a jurisprudence exam, paying a licensing fee, and then participating in annual training. Because Private investigators are civilians, not police or military, the same laws apply to execute our jobs. So, for instance, when I conduct surveillance I must obey all laws regarding privacy and distance. I have had to learn a great deal about public and private space as it pertains to paparazzi law in order to navigate what is legal in terms of gathering information.

“I mostly have had to learn by research as I go and through developing relationships with other P.I.s, lawyers and sometimes even law enforcement.”

Has Covid affected how you approach your art practice?

While I have had a pretty substantial increase in private investigation clients during the pandemic, I have found that doing fieldwork to complete my jobs has been very tricky. I have given talks and performances nationally about my work in years past but have not been able to do that during the pandemic. I have had to put a project on hold that I was starting work on in 2019 because it depended on collaborators. I am happy that I have just been able to resume work on it this month. I hope to get back to booking lectures, talks, and performances again soon.

Can you tell me more about your ongoing work ‘D.I.Y. P.I.’?

Do It Yourself Private Investigation (D.I.Y. P.I.) is an ongoing project that began with getting my private investigator’s license in 2017 after putting in the five years of investigative work. I documented that process, shared the work on my Patreon, at an exhibition in Albuquerque, and toured a series of performances and talks. I think that my work comes across the clearest when I am able to present it publicly sharing the stories and adventures of making it. I hope to get back to doing more immersive performances and presentations about the work I do.

Where do you draw inspiration from?

Oh, wow – lots of places! Living my own life and observing how other people move through their lives has provided the most inspiration for me. Facing the systems of oppression in my day to day living and helping others to empower themselves in navigating these systems is what fuels me to keep getting up every day and trying.

“Making art in those spaces of feeling disempowered has literally kept me alive.”

Music and film also inspire me greatly.

‘Dear Erin Hart’ is perhaps your most well-known work, what do you think in particular draws people to this artwork?

Dear Erin Hart, lends itself well to a wider audience for a few reasons. One is that it is about identity theft, which is prevalent in our culture at the moment so it touches on a timely issue. Identity theft strikes at something very vulnerable for most of us. Our identities are all we have that is ours and only ours so when someone uses our name or image to commit acts that we do not ourselves do, it feels like a real violation and loss of control on a deep level. I think that those who read what I did for this project (following the woman who stole my identity) as an act of revenge, they seem to appreciate how I took back my power from this person who wronged me. For others, they see the compassion I found for this woman who is living her life the best way she knows how. Over the time I executed the project and really for the years that have followed, I have come to see it as an act of restorative justice on my part and long to actually know this woman.

What advice do you have for young creatives looking to explore concepts of identity and surveillance?

I encourage young people to explore how surveillance impacts them personally and professionally as well as how it informs their own identity. I will say that it has been very valuable to me to learn as much as they can about the laws around surveillance.

I have found self-reflection about my own identity to be a critical part of how I research and explore it on a larger scale outside of myself. In terms of those wanting to explore identity publicly as their work, I would advise anyone moving into this realm to deeply consider how they present themselves publicly and privately.

“Sharing your story is an act of generosity and trust and sadly, not everyone who has access to our images and stories can be trusted to be respectful.”

Are you working on any other projects at the moment and what plans do you have for the future?

I am currently working on a collaboration called Practiced Disguises where artist and photographer Heather Sparrow is working with me to document the wide array of disguises I have employed in my work as a Private investigator. We are still in the early stages of bringing each disguise to life and I cannot wait to share this in the coming year or so. I am also working with a well known Canadian actor to create a movie or TV series about that part of my life. We are working with a screenwriter on the script now, which is getting pretty exciting. I think it will be really interesting to see how the project unfolds!

Credits

Images · JESSAMYN LOVELL

www.jessamynlovell.com/