Mathias Schmitt

“A photograph says more about you than the objects you capture”

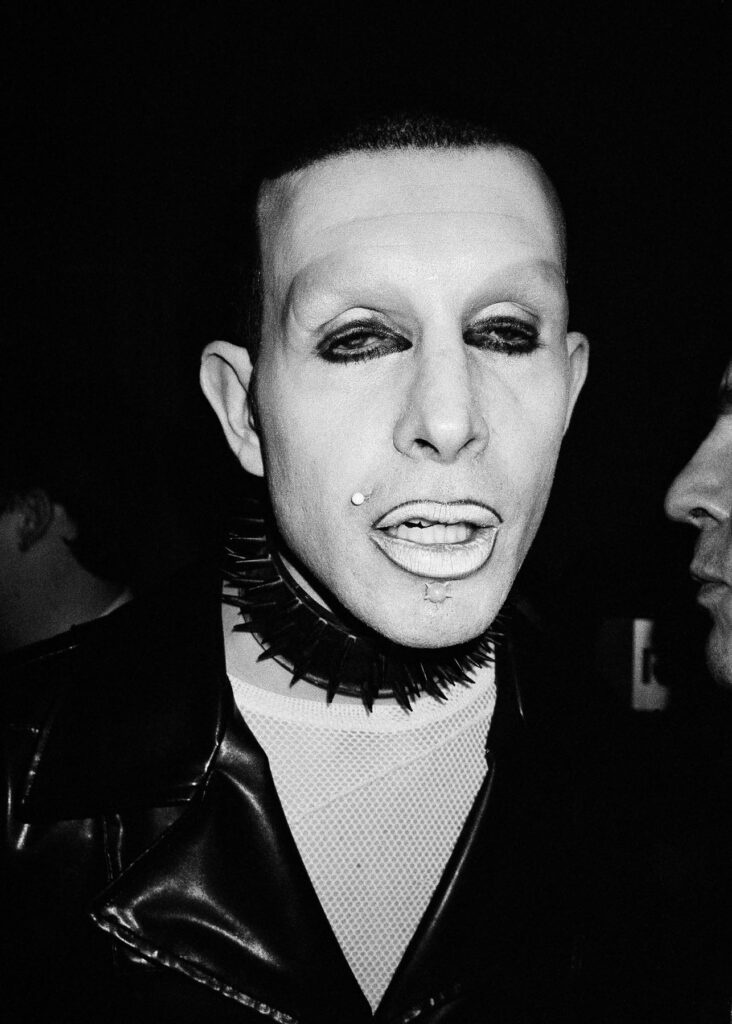

Taking us on a trip through the streets of Detroit, winding through the urban landscape in a Dodge Polara, passing old cafés and nightclubs – Mathias Schmitt tells a refreshing story of inner-city culture with his photography. Looking at his work as a whole, it presents itself as a cinematic mapping of an urban daydream. Capturing candid exchanges with locals and shedding light on the overlooked nooks and crannies of public spaces, Schmitt’s eye is unwavering, and never fails to channel the energy of the places he immerses himself in.

Inspired by the vibrancy and diversity of different subcultures, DIY aesthetics, music, fashion and photography icons such as Wolfgang Tillmans and Jürgen Teller, Schmitt’s work has a youthful spirit and reveals a strong love and appreciation for photography’s social potential and as a medium itself.

Finding inspiration and comfort in the everyday occurrences of city life and fuelled by a sense of inner freedom, Schmitt navigates urban photography with ease, constantly developing a sense of personal awareness.

NR Magazine speaks with the photographer to discuss how city life and the concept of identity has shaped his creative outlook.

You mentioned that Wolfgang Tillman’s book ‘Burg’ was a huge influence for you and your photography. Could you talk a bit more about that? What about this style of photography impacted you the most?

‘Burg’ hit me in 1998 when I was 20. Exploring different subcultures and aesthetics, this book presented me with a completely new world – it felt like a revelation. I didn’t know anything about cultural history, photo-technique or photography and its culture. While I was lightyears away from a full understanding, what affected me most was this certain kind of view, the glimpses, the candid faces, the natural collection of people, moments, and situations. I fell in love with this idea of being able to create images where I could share something with people who feel the same as I do, so I decided to become a photographer instead of continuing my plan of becoming a social worker.

Are there any other aspects of German culture that have influenced your work? And what was the photography scene like when you were growing up in Germany?

I don’t think German culture has specifically influenced me, but subcultures have always fascinated me. I liked the idea of being a part of something, of identifying with something separate from the mainstream. MTV was an issue back then, and magazines like Spex, Jetzt and Musikexpress drove me nuts with their photography. Kira Bunse, Sandra Stein, Wolfgang Tillmans and Jürgen Teller were people that I looked up to as well.

Some of your work shows an affinity for the city of Detroit. What other places do you draw inspiration from?

I can get inspiration from anywhere – a conversation, a person crossing the street, a train ride or just the desire to have a coffee at a specific place.

There’s so much joy in being able to travel to different places.

“An open and curious mind can bring you everything, even without asking for anything.”

Your work explores different aspects of urban life, capturing distinctive flashes of cities and their inhabitants. Are intimate moments or personal connections something you try to capture with your work?

Personal connections can be found in all sorts of things, like music, culture, fashion and food. I’m a huge fan of explorations – those distinctive flashes of cities and their inhabitants, of moments and their participants. Being in someone’s company with or without a camera can be a great gift. Sometimes you don’t know anything about the person in front of you, but it can also feel in some way very intimate when you’re both aware of that situation. I wouldn’t say that I aim to capture intimacy, but it is a very important aspect of taking a portrait.

You have a great interest in cars as well – where does this come from?

I like cars that have something to say. The presentation of a silhouette from a 1973 Dodge Polara or a 1969 Buick GS is fascinating to me. Imagining having a nice car trip for me, feels like a mental holiday.

How do you see yourself as the artist behind the lens? Do you try to influence your shots at all or is it more a case of it being a relaxed and natural process?

It is extremely important for me to be aware of when I can intervene and when I need to take a step back. Some pictures are accompanied by a certain casualness that is deliberate, rather than being something that happens by chance and from inexperience. Of course, I influence the frame, lighting, and shutter speed, but I’m a huge fan of sincerity. I’m not interested in phony smiles.

What aspects and aesthetics of city life stand out the most to you?

Being able to find everything you can imagine behind every corner, finding joy in privacy with strangers when you’re in public places, sitting alone in a café for 8 hours in a city you’ve never been to. Meeting people with different visions, different stories, finding places of joy – that’s exciting to me. I think these are the fascinating aspects of city life.

Has growing up in the countryside affected your attitude towards cities and more urbanised areas? Cities have a different kind of energy and vibrancy to them, but do you feel a particular connection with the rural landscape?

“Growing up in the countryside sharpened my senses for my surroundings.”

The isolation protected me from unwanted influences. Traveling from the countryside to bigger cities always brought about a sense of romance. I’ve always been thankful to come back to a calm place where I can separate my thoughts from what’s unwanted to what’s needed.

Do you find photography brings you a sense of identity and autonomy – particularly when visiting cities?

Identity is shaped by emotions, and photography gives me the opportunity to share these emotions. A photograph says more about you than the objects you capture. When I realised this, I fell in love with that approach, and I freed myself from all competition. I don’t expect everybody to understand or to engage with my work.

When I decided to become a photographer, I wasn’t aware of all the power it has as a medium, but I felt an immense freedom. The people I’ve met abroad and the situations I’ve been in with them has given me a sense of personal awareness.

Your series ‘Mittelkonsolen’ was inspired by the work of Hans Peter Feldmann and has references to the era of cassettes and CDs. You’ve also mentioned that reading music and skate magazines as a teenager had a big impact on you. Do you often try to channel a sense of nostalgia in your work? What is it that appeals to you about those times?

I think that using an analogue camera requires concentration, both for myself and for the participant. I’m a fan of the concept of nostalgia but I don’t particularly try to reference that in my work. We’re in a time of great technical development, but that’s not always enough. Everything must be faster, cheaper, easier – we want everything, and we want it now, no matter what.

‘Mittelkonsolen’ is an ode to a certain state of mind. The fact that you have to think about travelling and your choice of music, the atmosphere of your trip and its limitations – all that appears to me as something very logical and beautiful.

Have you discovered anything about yourself through your photography?

Separate from my images, I noticed a certain reservation in my work. I stopped caring about the specifics of how my work might be seen by others. Inner freedom is very important to me, and photography helps me channel that throughout my life.

Are there any aspects of your own life that you aim to interrogate through your photographs?

Besides photography, music plays a really important role in my life. Both mediums have almost no boundaries and provide me with a kind of shelter, allowing me to express and to address myself. Identity can be both fragile and strong, and I think the same applies to photography.

Credits

www.mathiasschmitt.com

Images · MATHIAS SCHMITT