Santiago Sierra

Santiago Sierra (b. Madrid, Spain, 1966) is a contemporary conceptual and performance Spanish artist whose oeuvre continues to be widely recognised and exhibited in major art institutions around the world. Known for his provocative and politically charged artwork that often addresses issues of social and economic inequality, labour exploitation, and human rights. Sierra’s work spans a variety of mediums, including installation, video, performance, and photography, and often involves the use of controversial materials such as blood, human hair, and excrement.

After graduating in Fine Arts at Madrid’s Complutense University, Sierra continued his artistic training in Hamburg. His artistic career began with exhibitions that marked a before and after in his work, such as the Minimal Art from the Panza Collection at the MNCARS in 1988 in Madrid and Zeitlos at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, curated by Harald Szeemann. There, Sierra found minimalism useful due to its syntactic character, which allowed him to incorporate reality into pure forms. In Mexico, Sierra’s work was influenced by the dense reality of the country, and their oeuvre began to weigh more heavily on reality than the history of art itself.

Sierra’s work serves as an outlet for critical thoughts surrounding the forms of violence imposed by the socio-political conditions of our time, engaging with marginalised groups, highlighting their struggles and drawing attention to their plight through his art. Sierra also often pushes the limits of what is considered acceptable, highlighting the presence of societal rules and limits.

He believes that dealing with those unpleasant themes surrounding hierarchies of power and classes and the exploitation of individuals is essential to defining society and the environment His connection with actors in that environment provides a necessary and engaging corridor for exploring these themes.

Indeed, PAC (Contemporary Art Pavilion) in Milan presented in 2017, Santiago Sierra. Mea Culpa, the first extended Italian anthology dedicated to Sierra’s work. It became clear that there is no art without a call for action, an appeal for individual responsibility. The title of the exhibition ‘Mea Culpa’ reminds us of that indelible debt. There is no specific definite answer but various meanings and observations foster a conversation. The mea culpa serves as a conscious push towards not only understanding ‘on paper’ where it went wrong but assessing our responsibility in the way power structures engage with the marginalised. When asked about the future, Sierra expresses distrust of the proposed future, emphasising the importance of the present and the consequence of our actions.

Santiago, it is truly a great pleasure to interview you, thank you for taking the time to participate in this issue of NR.

Could you tell us about your beginnings and your artistic training?

What was the catalyst element that prompted you into making art and diving deep into thematics such as nationalistic fanaticism, intolerance, war and racism?

What marked a before and after between my student exercises and my first works are exhibitions such as the one on the collection of Minimal Art in the Panza di Biumo collection at the MNCARS in 1988 in Madrid, the ‘Zeitlost’ at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, curated by Harald Szeemann (with whom years later I had the pleasure to work), or the ‘Anti-Forma Norteamericana’ in Madrid by José Luis Brea around the same time. That year I went to Hamburg where I spent two years. I found minimalism useful because of its syntactic character, and its lack of references to reality gave me something to do with its pure forms, which was to stain that minimalism with reality. So, for example, I placed a cube on the wall as Donald Judd would do, but the skin of that cube was an old and dirty truck tarpaulin taken from the port of Hamburg. Politically I was also clear about my side in the class struggle, but I would begin to develop that more in Mexico in 1995. In Mexico, it was like starting my artistic career again, but now taking into account a dense reality like the Mexican one, which begins to weigh more in my work than the history of art itself. This is why my work begins twice, first when it is linked to art history and then when the surrounding reality comes to the forefront. So my beginnings are linked to those two journeys, one to the north and the other to the south. We could place a third moment in my career at the beginning of the century when I started to work all over the world. From working in little alternative spaces with great difficulty, I then started to work a lot and with means in environments with a lot of visibility.

“The catalyst is the environment. The work emerges from the environment where it is made and/or where it is exhibited. On the other hand, the work of art is produced in the spectator’s head, so it is the subject matter that the public brings from home that we play with or manipulate.”

It is not the same to exhibit a war veteran in the U.S. as it is to exhibit it in Germany. The audience ends up making sense of a work of art with what they bring in their heads. The environment and the connection with the actors in that environment would be that corridor that leads us to deal with the unpleasant themes that define our society.

You have spent considerable time in Mexico (1995-2006) and Italy (2006-2010). Why those two locations and how did those aliment your work? Is there anywhere else in the world you would like to settle in?

My years in Mexico began with artworks on the street or in alternative spaces. My mission was to develop an artistic work as powerful as the reality I intended to describe. What I came out with, looking back, is a dirty minimalism that some have described as third-world minimalism. The role of the worker in society, or the painful lives of the urban grey masses, took centre stage in my work. From those years come my paid series where the work is activated by the intervention of salaried personnel. Around those years I did a lot of works bordering on vandalism such as GALLERY BURNED WITH GASOLINE [Mexico, November 1997], or OBSTRUCTION OF A FREEWAY WITH A TRUCKS TRAILER [Mexico, November 1998] and other forms of mimesis between my work and the monstrous Mexico City. In Italy, I came more as an artist applying the methods acquired in Mexico to another context, but my work never became centred on the Italian reality alone as it was in Mexico. Italy was a base from which to attend to international projects and a respite after my last year in Mexico spent in Ciudad Juarez making the work SUBMISSION (formerly word of fire) [Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, México, October 2006/ March 2007]. The violent reality of Ciudad Juarez made me long for the calm I would find in Tuscany. It was 2006 when I moved to Italy and that year I had also made 245M3 [Pulheim, Germany, March 2006] in the synagogue of Stommeln, Germany, a work that caused great controversy for the clarity of its statement, with which I was looking for in my place of residence. Also a place of rest and escape from a work whose density caused me considerable uneasiness because of the strong contestation caused by its exhibition. This polemic charge of my work was something that I never thought would be so strong, since at the end of the day, my work dialogues with the history of art as much as with the environment. My work arouses very passionate reactions and I attribute this to the change from alternative spaces where one works with little public and resources, but with great freedom to consecrated art spaces with great visibility and therefore subjected to the scrutiny of my detractors. At the end of the day, this was just the result of showing everyone what I used to show to a few friends and colleagues, and I got used to it.

I could live elsewhere than in Madrid where I now live, and I may have to decide where in a hurry if the European sociopathic politicians do not lower the atomic testosterone they bring with their damned lucrative war. I am not sure where I would go if I left Madrid but I have always loved working in India where I did pieces like 146 WOMEN [Vrindaban, India, 2005], 21 ANTHROPOMETRIC MODULES MADE FROM HUMAN FAECES BY THE PEOPLE OF SULABH INTERNATIONAL, INDIA (India, 2005/2006, London 2007)] or THE THROUGH (PART 2) [Bikaner, India. September 2016]. It is a place I like to frequent.

You’ve mentioned in an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist at the occasion of the opening of your exhibition ‘Dedicated to the Workers and Unemployed’, on show at Lisson Gallery in 2012, that one of your heroes and inspiration is Isidoro Valcárcel Medina, the pioneer of conceptual art in Spain. He’s said before “Art is a personal action that may serve as an example, but can never have an exemplary value”. For him, art only makes sense when it makes us aware of and responsible for our reality. Would you agree?

Do you have other artists or people in mind that have inspired you?

Isidoro has good phrases but the ones you mention seem to me to refer to a posture before the world, beyond art. We could change where it says ‘art’ and put ‘life’ and the phrase would work the same. Sometimes when we artists say art we mean the art we make. Evidently, art is an extensive phenomenon in the history of mankind and therefore it has been given an infinite number of uses. Leni Riefenstahl or any king painter from the Prado Museum is also art. Art also ignores reality as does minimalism for example. Art is diverse as is the human being through time. Perhaps the most obvious generalisation is that art will be owned by those who can pay for it. So the relationship between the work of art and its final owner determines its contents since the origin of human civilization, having been for millennia another instrument of the powerful. Isidoro is one of those people, and nothing links him to the final owner of his work because it is simply not sold as it lacks material existence and because the artist makes a living from something else.

It is easy to see the artists whose work I build mine off because I quote them constantly. For instance, the aforementioned work 245M3, in which long black pipes collected the smoke from car exhausts and introduced it into a disused synagogue, was a tribute to the German post-war artists who have influenced me the most. That work was built from a mixture of J. Beuys’ ‘Honey Bomb’ and Gustav Metzger’s Mobbile. The staging was reminiscent of Wolf Vostel’s decollages, the arrangement of the pipes inside the church was intended as a quotation to Eva Hesse, the documentary photos with pixelated pictures referred to G. Richter and so on. Not only contemporaries. Casta paintings (or mestizo paintings) were an artistic phenomenon that existed in New Spain and the Viceroyalty of Peru in the 18th century and inspired ECONOMICAL STUDY ON THE SKIN OF CARACANS [Caracas, Venezuela. September 2006] or Goya whom I frequently quote for example in THE WALL OF A GALLERY PULLED OUT, INCLINED 60 DEGREES FROM THE GROUND AND SUSTAINED BY 5 PEOPLE [Mexico City, Mexico. April 2000] is a version of an engraving by Goya in which the dead come out of their tombs. In general, I like to walk through places already travelled by others. In NO, GLOBAL TOUR [Various locations, 2009] for example, the NO belongs to everyone, I can’t keep it or attribute its authorship to myself and that’s why I use it because of its lack of originality and in spite of that, a singular work appears. I use asphalt or cement that people see every day, or cars that are ubiquitous icons, or I show people to other people. My work does not pretend originality because I do not believe in it, nor do I believe in creativity, which seems to me a monotheistic category, a quotation to the Creator. In reality, we all build our work on that of our predecessors by re-contextualising it and appropriating it to formulate something different.

Your work shines a light on the limitation of space for freedom. Occupation and definition are two functions in your work, mirroring our reality, juxtaposing freedom and constraint, individualism and community, nature and culture. Could you talk more about these elements and what they mean to you? As an artist, do you feel free to think? Have you ever felt limited?

On February 3 an exhibition of mine closes in Madrid. It has two floors. The exhibition on the ground floor is open to the general public and the one on the second floor is a private exhibition which is by invitation only. This is explained on the room sheet:

‘On the first floor of the gallery — where the exhibition entitled ‘?’ is on display — the right of admission is reserved exclusively to those who have received a personal invitation. The contents of this exhibition will remain hidden until it has ended by means of a non-disclosure agreement aiming to protect it from those who might be offended; gearing it solely to individuals known to be open-minded independent thinkers. In this way, we hope to avoid those who are outraged by anything that has not been curated for them by an algorithm.’

On that floor we exhibited SPANISH NATIONAL FLAG SUBMERGED IN BLOOD [Madrid, Spain, October 12th 2021] and SPANISH NATIONAL COAT OF ARMS STAMPED WITH BLOOD [Madrid, Spain, October 12th 2021], two works that if exhibited to the general public would not only run the risk of having to cancel the exhibition but could attract violent elements to the gallery, putting at risk the integrity of its workers so we proceeded preventively.

We all know that freedom is a word that defines something that does not exist. To be free is an aspiration, not a reality. I like that you ask if I feel free to think, not if I feel free but free when I think. There you hit the nail on the head because it is not so much the freedom of expression that is denied us but the freedom to think. Millions are spent every day to appropriate our thoughts by filling our minds with irrelevant content, garbage or fears and this makes it clear that it is freedom of thought that we should be concerned about. I don’t know if self-diagnosing myself in this regard would have any value, I imagine I have come a long way in my own emancipation and art has helped me in this but being a freethinker is also just an aspiration. We all bring a reactionary inside during the educational processes, during the consumerist leisure or through the mass media and we have to get it out.

I have always felt limited but this is not an anomaly, even in the freest and most egalitarian society it would be because from physical to human laws the world will always have rules and therefore limits. In my work, I often point to those limits by placing myself on the edge of what is acceptable.

I would like to talk about a performance work of yours: Line of 160 cm tattooed on 4 people, Salamanca, Spain, 2000 which saw four prostitutes addicted to heroin, consenting to be tattooed at the price of a dose. Two heroin addicts were shaved with a 10-inch line on their heads in exchange for one dose. I found it to be two very emotionally charged pieces, because to me it says a lot about the state of our society and how far the system has gone into surrendering people to accept certain things. I think it might have been easy at first for the audience to think you were exploiting these four prostitutes or these two heroin addicts, but the intention was to unmask the exploitation that exists outside. Why did you want to tackle these particular thematics?

Has there been a governmental action taken after the making of these artworks? Do you think the situation has evolved in these areas in which heroin was at the time heavily used? Do you think the audience was receptive to these series?

Is Picasso’s Guernica a painting that honours Nazi aviation for its success in the annihilation of the civilian population? No, it is not, even though during the recent NATO summit in Madrid, where we saw the Prado Museum used as a picnic area for murderers, we could also see a group pose in front of Guernica by the couples of the warlords. That the directors of the Prado Museum and the Reina Sofia National Museum used Goya’s Disasters of War or Picasso’s Guernica as a photo call of neo-Nazis does not mean that Goya or Picasso was. The betrayal of these institutions with art and their intentions is very clear. I cite this case because it is well-known and easy to understand rather than to compare myself to these authors. I have never read in the press to ask the head of the Prado about the merendola of genocides or the Reina Sofia for this matter, or directly for having directed a Museum that bears the name of the Queen that Franco left us, the same one that went to the German aviation to raze Guernica to the ground. Guernica is like Montezuma’s plume; it is a spoil of war and it is exhibited so that it is not forgotten who defeated whom. I say this not to evade the answer but because here there’s no confusion and everything seems transparent while something as pristine as saying how much a model charges in the urban lumpen of Puerto Rico is an unacceptable act of exploitation and you don’t know how many times I have heard it. So amazing that we even have a book of interviews where I keep responding to that accusation from the most disparate angles. Almost every city has a school of fine arts with models posing. I was in one like that in Madrid. If you paint a picture in which you portray them you can call it a thousand things, but if you call it Young Romanian Girl Posing Nude and motionless for four hours a day at 9 euros an hour, you will be accused of being exploitative, just for saying how things are in your local fine arts school. Now step away from that school and tell us what you see, is the exploitation still there or is it gone?

Being paid for being a worker is essential. For whom? For the worker. People are perplexed when they find out because we move among people who do not work. If you tell them how much they are paid, you will see what faces they make, like in a movie. And if it is because of drugs, it is funny that living in a narcotised society we have to remember that the junkie, the one that everyone looks down on, is a person. I don’t know if there is anyone left in our society who sees it that way with so many zombie movies. Now in the U.S., there is a plague of Fentanyl which is 60 times more potent than heroin. Maybe the gentlemen visiting NATO museums know more about this than I do.

Your use of skin or humanity as a canvas recurs in other works such as Line of 30 cm tattooed on a remunerated person, Regina Street # 51, Mexico City, May 1998, Line of 250 cm tattooed on 6 remunerated people, Espacio Aglutinador, La Habana, Cuba, 1999. Why was it necessary to disclaim that these people were paid?

It would be hiding the reason why it was done from the worker’s point of view. So it was very necessary to say it and to do it in the title. The person paid so much to do this other thing, because that’s how you sum up what it’s all about, clearly, without embellishment. The more money you put in, the longer the line you can tattoo. A few years ago I did a book in which the participants were long-term unemployed. I hired them to write over and over again as if it were a school punishment, a sentence that said: Work is a dictatorship. Obviously, for those who do not have to offer their body, their time or their intelligence on the market for the benefit of a third party and earn enough to replenish their energy and return to work, this is not a dictatorship. But for those who have to work, it is. Everything is a matter of perspective and the essential thing in perspective is the point of view.

Do you think that your work only gets completed with the audience’s active participation in it?

The work of art is produced in the head of the viewer. Sometimes actively and sometimes passively. In the end, this equates to art and demagogy, but it is so, art is a story and the human being is built with stories. We do not have hundreds of pages to explain ourselves, sometimes it is only an image that conveys everything, so the work must be a quick poison and a slow balm. Perhaps that is the reason for my interest in minimalism because, with a visual stroke, you understand the whole work with admirable effects of presence and evidence. There are pieces that also function as pure stories without anyone seeing them. For example, in 100 HIDDEN INDIVIDUALS [Calle Dr Fourquet, Madrid, Spain. November 2003] that nobody except the organisers saw. The public took that piece home and didn’t even see it, because the work of art is produced in the spectator’s head.

90 cm Bread Cube, Mexico, 2003 is a 90cm bread cube, specifically baked in the format indicated in the title and gifted as a charity in a shelter for homeless people in Mexico City. Could you talk about the installation, the message behind and its reception?

This work showed an outline of a work of charity. It was to feed the hungry. A large bucket of bread was made and delivered to a soup kitchen. The curiosity about the large edible object was at times very Kubrick in 2001. Charity is a form of social intercourse that especially bothers me because it is always a public relations operation in which the funder is seen as a good person. The bread didn’t pay for any service rendered, it wasn’t a salary, it was a given. Then it was about filming this and I asked Artur Żmijewski to do it, that’s why it is one of my few colour videos. When the action took place the participants were the audience as well. The general public only knew the video.

I have used food a lot as a generator of action. In the trilogy of PIGS DEVOURING PENINSULAS [Various locations, 2012/2013] or in CUBE OF CARRION MEASURING 100 x 100 x 100 cm [Coast of Oaxaca, Mexico, September 2015], where this time it was vultures satisfying their hunger. Hunger is something very basic, very primary, and it makes actions with food always very simple to organise, because the end is clear; they eat it. In these works, he spoke of the need and hunger as what attracted the homeless of central Mexico who came that afternoon to the social centre, in hunger and tiredness. Those were simple actions that justified the portrayal of that extreme world we can end up in if we are not careful. It is the social panic of zombie movies that were also shown in THE CORRIDOR OF THE HOUSE PEOPLE [Bucarest, Romania, October 2005].

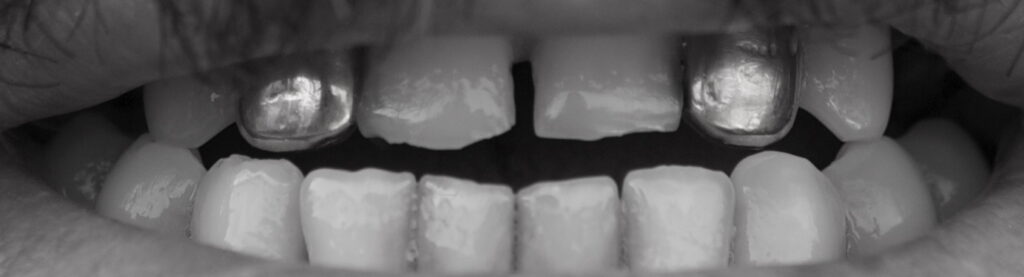

Could you talk about your piece Teeth of the last gipsies of Ponticelli, Ponticelli, Naples 2008, a series of photographs of the teeth of the last two gypsy families of Ponticelli, Naples? A few days after, their houses were burned. What made you take those photographs?

In Naples and other parts of southern Europe, attacks on Gypsies have been occurring in a similar pattern; they are accused of stealing a child and the mob goes after them. During the work of approaching the Gypsy people, we came across a house burning and were able to film it. The gypsies that show my teeth in my piece were the last ones left in the area. I was curious to see up close how their famous gold teeth in many cases are painted with glitter. We took these photos with the gypsy people who had not yet fled and paid them for their services as models. There is a standard treatment towards the victims to generate tenderness, and it is not considered as a seed of hatred that is getting into society. An abused person is a person who is going to show you his teeth. And I liked that idea of not just showing them as a passive mass, but as people who show you their teeth. I love the effect because it’s an effect that has to do with the animalistic. An animal understands this piece. An animal that shows you its teeth knows perfectly well what you want to say.

With these photos, we did a small campaign in Naples because we didn’t have much money [CAMPAIGN OF THE TEETH OF THE LAST GYPSIES OF PONTICELLI, (Naples, Italy. May 2009)]. And there we exhibited these teeth. The result is that the whole city seemed to have teeth. The windows became eyes. Using their teeth seems to me a very good method to portray cornered masses. It is a method that we have repeated, which in fact is the basis of the exhibition that we are closing right now at Galería Helga de Alvear (December 2022 to February 2023, Madrid). It is a collection, this time larger, of teeth taken at the borders of Tijuana. They are teeth from groups of migrants who cross in caravans of 1000 or 2000 people all together to avoid being assaulted. They arrive in Tijuana and stand there. I have a large collection of photos and also of the eyes of all these people, which was part of the exhibition “2068 Teeth”. This presentation of the Tijuana dentures included a sound piece. The sound on the first floor is CUMBIA REBAJADA LOWERED AND INVERTED [Madrid, November 2022]. Cumbia rebajada (lowered cumbia) is a very popular musical phenomenon that occurs in northern Mexico when DJs discover the success of playing cumbia from Colombia at lower revolutions per minute than the original recording, creating a new sound that is denser and sadder than the original. By manipulating this lowered cumbia again, lowering it even further and inverting it, we get the sound we hear on the ground floor.

The Penetrated, Terrassa, Spain, 2008 is a film that shows men and women of different skin colours performing the sexual act of penetration and being penetrated. As in the binary system, the partners change until they went through all combinations of sex (male and female) and skin colour (black and white). Could you talk about this work and its allegory not only to domination but as well to sexual exploitation?

“Que te den por culo” (Fuck you in the ass), is a phrase that is not used to describe a pleasant, consensual sexual relationship, but as a threat of rape. It synthesises the desire to get hurt, to have a bad time. So, sodomy comes in popular culture or in popular expressions, associated with doing harm. ‘Joder’ also in Spanish has a double meaning. To fuck can be to make love, to fuck, but it is also to be hurt. ‘Me jodieron’ means that they ‘hurt me’. Around this phrase and also taking into account the ‘unproductive’ sex, I brought in my head a phrase by Jorge Luis Borges who said that he hated copulations and mirrors because they reproduce people. That’s why the place where we shot LOS PENETRADOS [El Tórax, Terrassa, Spain. October 12, 2008] was all covered with mirrors. They were all copulas and mirrors, but without reproduction. Of course, he also spoke of the relations of domination, of the male/female relationship, of the black/white relationship. All these tensions that have to do with this so-called ‘melting pot’ we live in, which is nothing more than a constant class struggle, mirrored and reflected in a thousand ways: with reflections in sexuality, with reflections in the colour of our skin, with reflections in the way we talk. It is the pornographic work with the largest number of participants ever filmed in Spain. But nevertheless, it was all very orderly, all very repetitive. There was such order that it didn’t really call for excitement. It is a tremendously anticlimactic work in spite of everything. I was very struck by the amount of public that came to the show. There were lines of people every day. But I was even more surprised when we showed it in New York, at Team Gallery, because normally in New York we might have a percentage of the population of African origin that is maybe 30 or 40 percent of the total public. When we showed this piece in New York, there was about 60 percent of the public of African descent. And I think this was because of the ending. In all the series that were there, it started with the whites penetrating the blacks, but the last scene of the film was the blacks penetrating the whites. In the sequence of events, finally, they were the ones penetrating. Black men anally penetrating a white man. Suddenly it takes on a tone, if not emancipatory, at least of a certain revenge, of a certain aesthetic revenge, which I think attracted many people to see it.

We had difficulties shooting in Spain. Just when we were shooting, they had passed a law in Barcelona that criminalised the practice of prostitution in the street. This doesn’t sound strange apparently, but the problem is that the police see a black woman and think she is a prostitute. So they were fining black women just because they wanted to, because the policeman wanted to. So they were intimidating black women in Barcelona during that period. It was very difficult for us to get close to the black women of Barcelona and you can clearly see in the video that some of them are missing, and that we didn’t complete the series. I don’t like the pieces to come out exactly as I have planned them. I also like that everything that comes out is the result of taking a piece of the real world. In other words, it’s not Hollywood what I do, but it has to do with the reality of what I find and I want those mistakes to have importance in the work of art.

A few of your works were made in association with external organisations. For instance in 2012 with Artifariti for World’s largest graffiti, Smara Refugee Camp, Algeria; in 2001 for Person in a ditch measuring 300 x 500 x 30 cm, Space between Kiasma Museum and the Parliament building, Helsinki, Finland for which you made contact with an association for the homeless; in 2002 for 9 Forms of 100 x 100 x 600 cm each constructed to be supposed perpendicular to a wall, New York, United States, you required the services of local job centres to find the participants. Why was that important for you to involve external non-profit organisations in your work?

My studio is more like an office with people calling on the phone, looking to see how to solve things, but it is not a place of production. I have friends that produce their works as a man makes chairs in a carpentry shop. That’s not my case, I work with the outside world. So organisations and people of all kinds participate. Even to set prices, there are organisations that tell you what to pay and what not to pay. I also do a lot of work trying to link up with people who are doing a good job and include them in some way and relate to them. For example, now with this piece of the SPANISH NATIONAL FLAG SUBMERGED IN BLOOD [Madrid, Spain. October 12, 2021], it was a real parade of people, not only from the art world but people who had a social concern to which my work gave an answer. So yes, there is a lot of collaboration. But there are also a lot of people who really help you because they agree with you. And the clearest case is this one of the flag submerged in blood, where there was no payment, you can’t buy people’s blood, it’s not legal. So people gave it to me. And finally, it is a work that is not from the studio, it is from the outside world and therefore is linked to organisations, to people, to specific characters or even to the lumpen many times. But it is a work that begins when I close the studio door and go out into the street.

A strong visual presence can be noticed in your body of work, for instance in 50 kg of plaster in the street, Madrid, Spain, 1994 depicting each vehicle’s journey on the floor as a homage to the strong presence of the construction sector in Madrid. I really liked the contrast of the white plaster outlines with the asphalt. The same with 50 litres of gasoline in an abandoned field, Madrid, Spain, 1994, which left a large black stain on the ground and with Black posters, staged in various cities, 2008-2015, which saw the collage in a mass of black posters on buildings, cars, thus providing a visually striking counterpoint to the advertising messages in the public space. Or with Canvas measuring 1.000 x 500 cm suspended from the front of a building, New York, United States, 1997.

Was it important for you to have these kinds of messages be so visually direct, contrasting with the environment, in a graphic way?

I spend more time on the street than in museums. I see more art in the street than in museums. I see it constantly on stickers, on lampposts, and in writings on walls. The vandalism acts that the urban masses do on weekends have also interested me a lot. I think they are very much related to Jackson Pollock’s Action Painting, for example. And so my work refers a lot to that, to the street. I think I’d liked to do all-terrain work, but I think there’s an abundance of streets, that’s my place. In Dublin, during an England-Ireland soccer match – I don’t like soccer of course, it’s something I abhor, like all mass events – I had the city of Dublin all to myself. Everyone was watching the game. So, I spent my time lifting up all the car windshield wipers I came across during the soccer match without anyone saying anything to me, because everyone was watching the soccer game. The result is a beautiful, surprising work, with all these windshield wipers like little graphic stripes denying reality. Of course, it is something that I think about, the graphics of the image, everything that is graffiti I love, although I love it as a texture. I don’t read who wrote it or what name is being advertised to me, but the stains, the colours, the combinations. Working in the street is funny because it is completely the opposite of working in a museum where ‘authority’, in quotation marks, helps you. In the street, the authority chases you, you have to be careful. There is also a time for all that. I think I had much more fun doing this 20 or 30 years ago than I do now, but I always like the street, going back to it in one way or another.

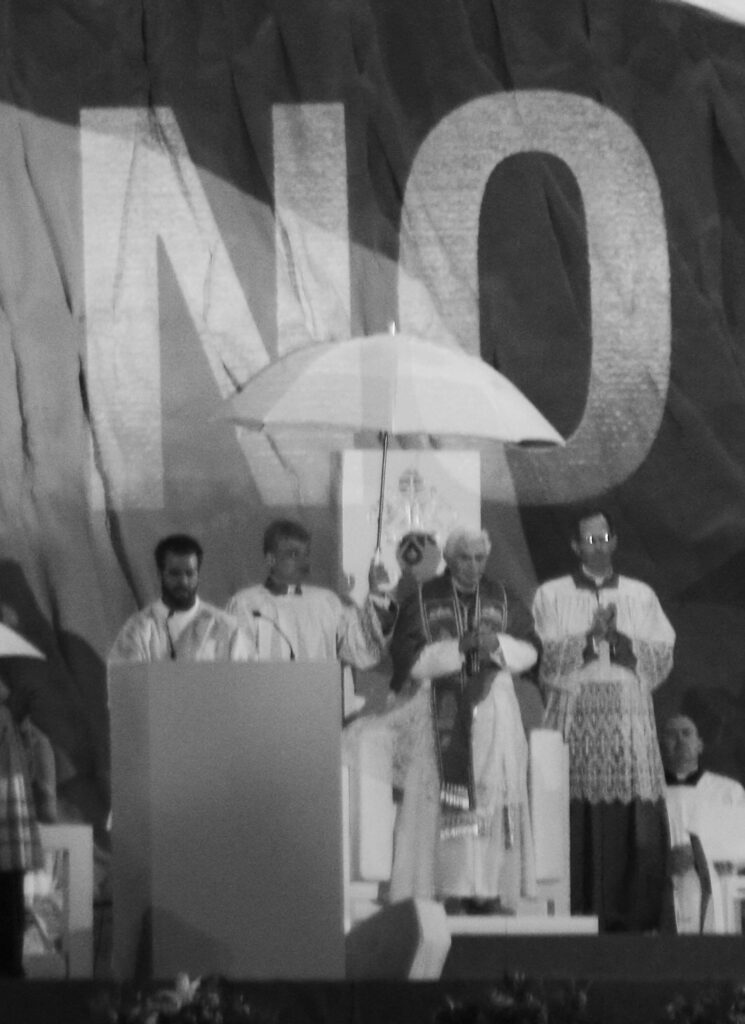

NO projected above the pope, Madrid, Spain, 2011, realised in collaboration with Julius Von Bismarck, saw the projection of the word NO during a few of Pope Benedict XVI’s appearances in protest of his visit to Spain. This is one of many instances in your body of work, in which you take the subject of religion. How was this event staged?

Religion is the ancient method of social control that still retains some effectiveness although I believe it has been largely superseded by the mass media and by a law that goes into every minute detail of daily life. Social control right now does not need religion but it helps and it is there. Everything that is spread from religion, and especially from the Catholic religion, is the denial of our own body, the denial of our own freedom, the denial of our own intelligence, the submission to the criteria of some millionaire lords who simply make money with your candour. It is necessary to answer. When that work took place in 2011, months before the arrival of the Pope, there was a great concentration, one of the great demonstrations in Madrid that are still known as the 15M. A left-wing demonstration where people showed their weariness towards the structure of political parties and towards a politically delirious Spanish reality, with the entire political class stealing from the rest of the population by the bucketful. And this youth day in Madrid was planned with the presence of the Pope, of this Pope who has just died, who was ugly and bad, as a response to this 15M. They brought young people from all over Europe, young Catholics, and they filled Madrid. Normally in Madrid, the police are always on top of the youth with a repressive attitude. During this Catholic meeting the city was theirs like other times, only this time we were waiting for them. I knew the work of Julius von Bismarck, who by the way seems to me one of the most important people of his generation. He is a brilliant artist and a good person and colleague. And we collaborated in the production of this work, which was simply projecting a NO behind the Pope. It was part of my NO, GLOBAL TOUR [Various locations, 2009].

The device we used is a device invented by Julius von Bismarck called Fulgurator. It is a device that hacks analogically. That is, there is a camera that as soon as it detects a nearby camera emits a flash, then responds by very quickly emitting another flash. But this flash contains an image, a very brief image that is not captured by the human eye but is captured by the camera. In other words, what this device does is hack into other people’s photographs. Any photograph preceded by a flash activates the Fulgurator and it sends you an image. Julius had used it on multiple occasions and we used it to get these huge pictures of the Pope with a NO behind him. They are photos that we might think are Photoshop, but no, they are actual photographs of a real event that happened on a large scale. Suddenly we had thousands of people, we projected huge NOs and only the photographer saw it, the rest of the people did not. We also projected it on policemen, on pilgrims. Anyway, there is a long series on the subject.

I would like to delve now into your set design work for the Balenciaga Spring Summer 2023 show held in Paris. The Parc des Expositions de Villepinte convention centre on the outskirts of Paris was filled with 275 cubic metres of mud, creating a mud runway for the show. How did the collaboration unfold? Was this your first collaboration within the world of fashion and would you do it again?

Balenciaga was a commission, a very specific commission to make the scenography for its fashion show [LOS EMBARRADOS (THE MUD SHOW / BALENCIAGA) (Paris Nord Villepinte, Paris, October 2nd, 2022)]. I thought it was wonderful to do the opposite of what someone would expect from a fashion show, reaching a situation where we muddied the audience, we muddied the models, where it was difficult to walk. I liked it a lot. It was about getting the elites muddy, that was the concept, to mud the elites. The mud could be a synonym for reality or it could be a synonym for a Europe that is on the verge of being blown up by the stupidity of war. It brought back a lot of reminiscences, a lot of memories. It reminded me a lot of the phenomenon rasputitsa, which occurs in Russia, Ukraine, in Eastern European countries, where twice a year, during the autumn rain and during the spring, snow melts and you can’t get through because of the amount of mud. The evolution of the news day by day confirms to me how accurate the piece was. It is indeed a muddy elite but at the same time a muddy environment for everyone. I think that in this fashion show, we really managed to represent the reality in which we live in a very powerful way, through fashion.

Is there any particular performance of yours that has impacted you more than another?

Yes, there’s a work I often remember because of its intensity, THE CORRIDOR OF PEOPLE’S HOUSE [Bucarest, Romania. October 2005] by Minhea Micnan. For this piece, we built a black corridor (240 meters of longitude per 120 centimetres wide and 2 meters high) inside the house currently occupied by the National Museum of Contemporary Art. That area was previously devoted to the personal rooms of dictator N. Ceaușescu (1918/1989). The corridor crossed through the 2 stories assigned for exhibitions in the building, but it crossed in the shortest possible way: going from the entrance to the stairs and then to the exit. 396 adult women were invited to fill that space for two hours at midnight on the 14th day of the month. Placed on both sides of the corridor, the women were ordered to repeat the phrase ‘Give me money’, literally and in Romanian. For this work, each woman received 20 leis (about 6 euros) and they also kept the money earned through the beggar. The audience could only access it individually, one by one, passing through a weapon detector placed at the building’s entrance. The whole action was very uncomfortable for the visitors and workers due to various reasons such as the detector at the entrance, the time of the day in which it took place and the abundant rain. It had a lot to do with the social panic of zombie movies.

Santiago, what is your idea of the future?

We dedicated a piece to the future in Valencia [BURNED WORD (El Cabanyal, Valencia, Spain. July, 2012)]. In Valencia, there is a very nice area because it is close to the sea, which is the Cabanyal, which are working-class neighbourhoods. A working-class neighbourhood with beaches, where Sorolla painted many of his paintings of boys on the beach bathing. And of course, being a working-class area on a beach, real estate greed fell on them. When I was there the whole neighbourhood was fighting to stay alive, not to be destroyed by the speculative vortex and lose their homes and be given to tourists who spend a week in Valencia and leave. And well, I got in touch. That was part of an exhibition called ‘Periferias’. My piece was to use a very common technique in Valencia, which is the ‘fallas’. The ‘fallas’ are sculptures that are made every year to be burned. I thought it was a fantastic idea to make a work specifically to be burned. So I worked with Manolo Martín, one of the most powerful ‘falleros’ there, with whom I would later work again. We made, with the typography that I usually use, the word FUTURO. Once we had it there, we set it on fire and watched the future burn. Evidently, the future is death. Our future. For that is what awaits us. Eons and eons of nothingness, of emptiness, of not existing, of not being here. Therefore the future does not seem to be something very interesting. And yet, it is something that from the institutional discourse or as a culture, as humanity, is all the time being put before and put on. Hold on, resist, because in the future this is going to be wonderful. Yes, now we are reforming this or there are works in the street, but in the future, this street is going to be wonderful. The future is at the same time, from an institutional point of view, like the heaven that is promised to us. In the future, our country is going to be at the head of I don’t know what. There is something religious about it. When in reality the future is death. There is a vindication on my part of the present. The present is the only thing that exists. We have to take into account that our actions in the present have consequences. But apart from that, the future is something to burn. What matters is the present. The future that is proposed to us is something I don’t want to go towards, not only because it is death, but also because it is an evolution of humanity that is more and more unstable, less and less reliable. It’s going to make us all uncomfortable to leave for those who stay here.

Credits

- 10 PEOPLE PAID TO MASTURBATE

Tejadillo Street. Havana, Cuba. November 2000 - 10 INCH LINE SHAVED ON THE HEADS OF TWO JUNKIES WHO RECEIVED A SHOT OF HEROIN AS PAYMENT

302 Fortaleza Street. San Juan de Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico. October 2000 - 160 CM LINE TATTOOED ON 4 PEOPLE

El Gallo Arte Contemporáneo. Salamanca, Spain. December 2000 - 20 WORKERS IN A SHIP’S HOLD

Maremagnum Mall and pleasure-boat moorings in the port of Barcelona. Barcelona, Spain. July 2001 - 68 PEOPLE PAID TO BLOCK A MUSEUM’S ENTRANCE

Korea, 2000 - 50 LITERS OF GASOLINE IN AN ABANDONED FIELD

Los Focos. Madrid, Spain. December 1994 - HIRING AND ARRANGEMENT OF 30 WORKERS IN RELATION TO THEIR SKIN COLOR

Project Space, Kunsthalle Wien. Vienna, Austria. September 2002 - 133 PERSONS PAID TO HAVE THEIR HAIR DYED BLOND

Arsenale. Venice, Italy. June 2001 - 90 CM BREAD CUBE

Plaza del Estudiante, 20, Mexico City. July 2003 - CAMPAIGN TEETH OF THE LAST GIPSIES OF PONTICELLI

Naples, Italy. May 2009 - 78 PHOTOGRAPHS OF EYES OF MIGRANTS IN TIJUANA

Instituto Made Assunta mixed shelter, Por los Derechos Humans de America mixed shelter, Casa del Migrate mixed shelter, Movimiento Juventud 2000 mixed shelter, Movimiento Juventud 2000 men’s shelter, Enclave Caracol social dining. Tijuana, Mexico. February 2019 - THE PENETRATED

El Torax, Terrassa, Spain. October 12th, 2008 - CANVAS MEASURING 1000 X500 CM SUSPENDED FROM THE FRONT OF A BUILDING

Seventh Avenue and 29th Street. New York City, United States. September 1997 - NO, GLOBAL TOUR (IRELAND)

Several locations. Ireland. October 2017 - NO PROJECTED ABOVE THE POPE

Madrid. World Youth Day. August 2011 - HOUSE IN MUD

Kestnergesellschaft, Hannover, Germany. February 2005

All works courtesy of Santiago Sierra