Hicham Benohoud

Social Fatalism, In Frame

1980s Morocco. Museums were absent and contemporary art circulated mainly as photocopied images and thin exhibition pamphlets. For Marrakech-born Hicham Benohoud, this scarcity became a site where imagination took root precisely.

His earliest encounters with artistic form arrived through reproductions brought by teachers who themselves had limited access. As a visual arts teacher in Marrakech, he entered a system shaped by hierarchy, monotony and one-hour lessons repeated across thirteen years. It was within this compressed temporal frame that his photographic practice emerged, first as endurance and then as a mode of inquiry into authority, embodiment and fragile social negotiations.

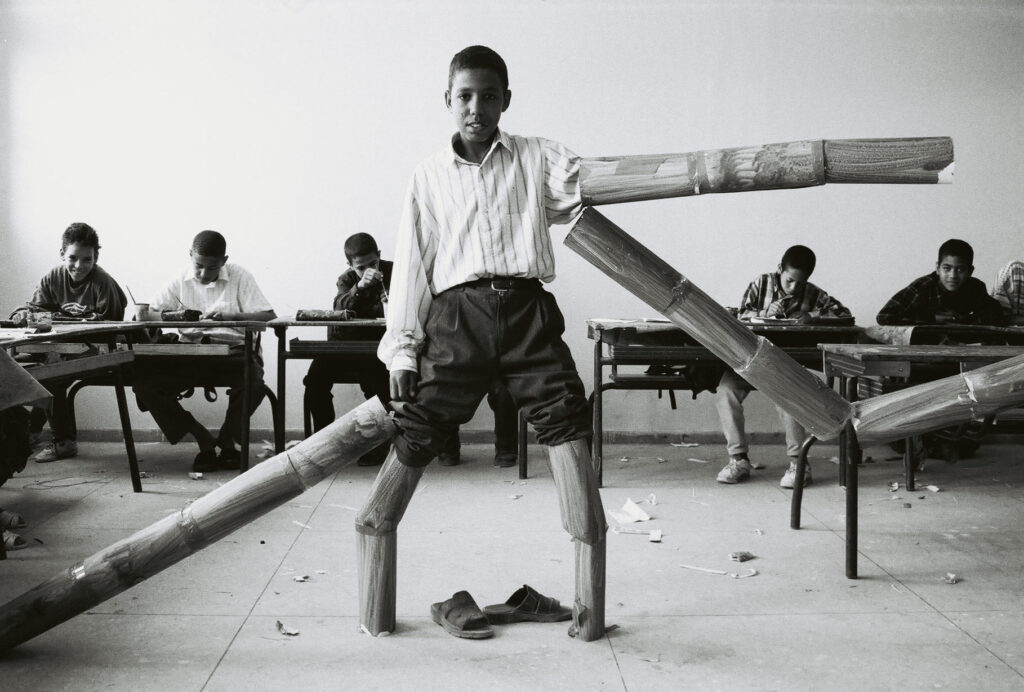

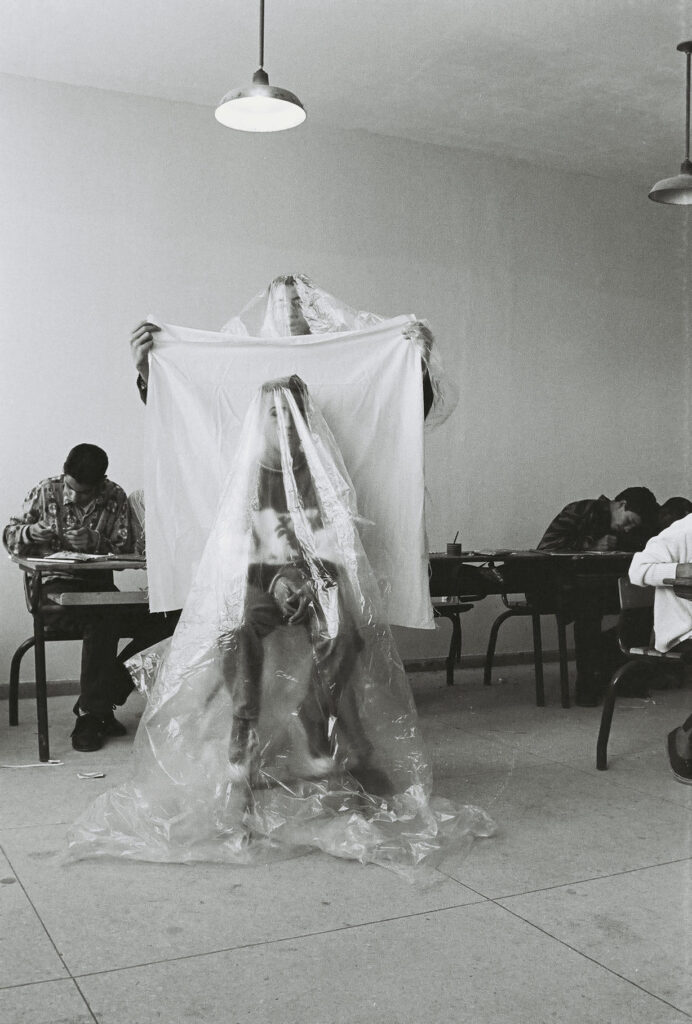

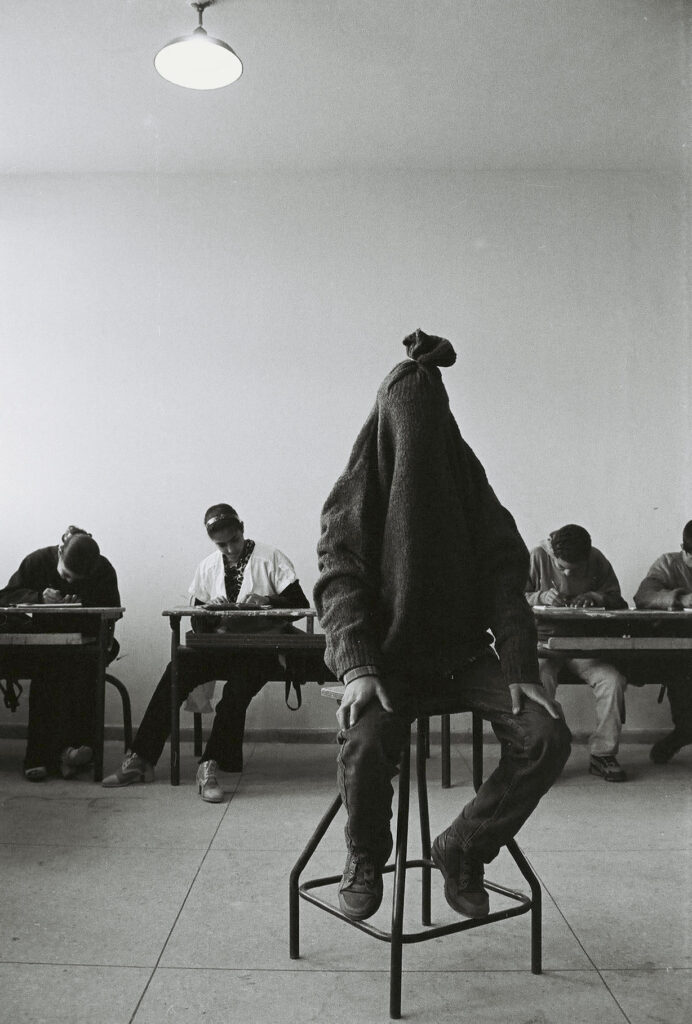

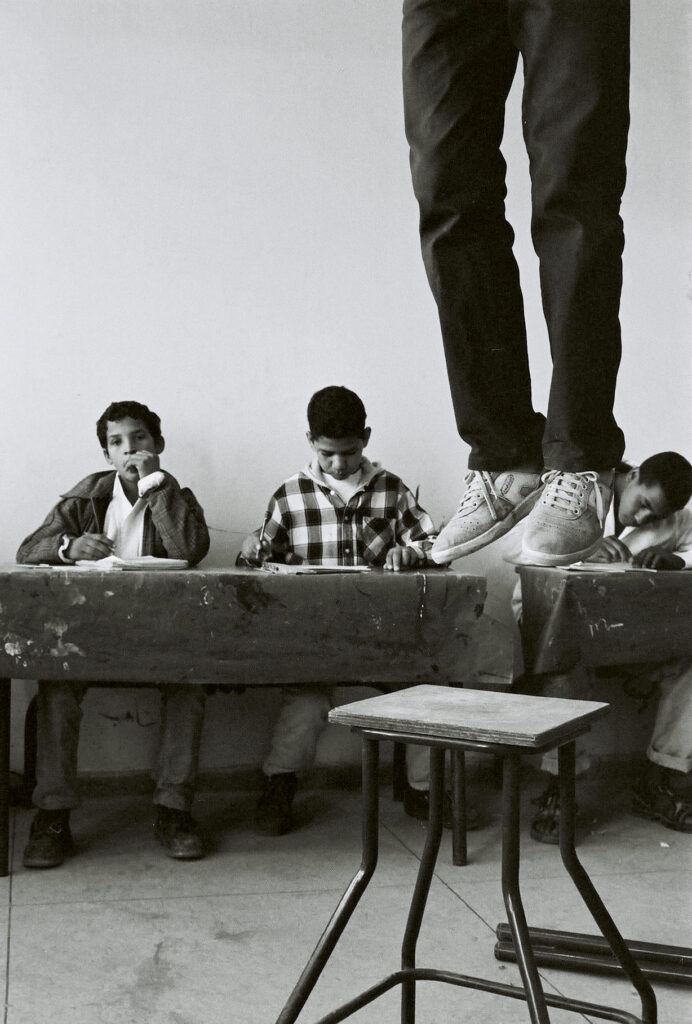

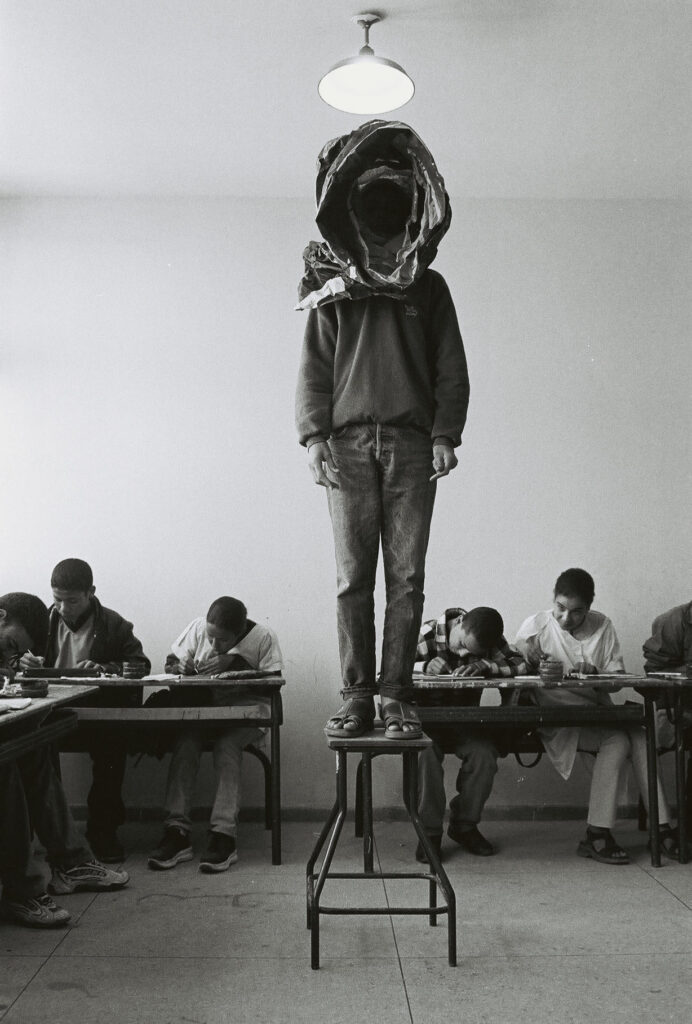

Across landmark series such as La Salle de Classe, which received the 2025 Paris Photo–Aperture Photobook Award, and Acrobates, Benohoud stages bodies in states of tension, distortion, suspension and erasure. His images reveal what is often invisible in Moroccan society: conformity, imposed discipline, inherited moral geometries and the small ruptures beneath them.

In this conversation, Benohoud reflects on confinement, authority, distortion and the classroom as a microcosm, a space where the desire for expression confronts the weight of tradition.

You grew up in Marrakech at a time when contemporary art infrastructures barely existed. How did this landscape of scarcity shape your earliest sense of artistic possibility?

I am 57 years old now, and when I was 15, 16, 17, I was already studying fine arts in high school. In the early 1980s, 1983, 84, 85, 86, there were no museums in Morocco, no galleries. There was supposedly a gallery far from Marrakech, but I never went.

There was no internet. So where could we see anything? When my fine arts teachers spoke about a particular Western movement, surrealism, impressionism, abstraction, they brought us catalogues, art books, magazines. I do not know where they found them, but they had a small amount of documentation.

When we discussed Moroccan artists, they brought small exhibition catalogues. At the time, Moroccan art was mostly Arab expression. In the capital, there was one major gallery, but it was not run by a Moroccan. It was run by a French or Swiss woman, I am not sure. In any case, not Moroccan. So the works we “saw” existed only in photographs, never in reality.

Everything was theory. Art history from prehistoric art to American Pop was studied in books, very few images, almost no physical encounter. I had not yet imagined becoming an artist; I had no personal artistic process. I was simply a classic art student shaped by absence.

Morocco carries a deep history of social fatalism, where roles feel pre-assigned and unquestioned. How did this atmosphere shape your early understanding of discipline, authority and the body?

After high school, I earned a fine arts baccalaureate, which included art history up to the 1960s and early 70s. Then I studied for two years at the regional teaching center, an institution that trained visual arts teachers, not artists. I learned pedagogy, how to teach adolescents.

I still was not an artist then. When I began teaching in 1989, I taught technique, drawing, basic sculpture, to students aged 11 to 15, once a week for one hour. Their abilities were limited and the schedule was rigid. For thirteen years I taught under those conditions.

During those years, I lived somewhat cut off. Few social ties, few friends, rarely visiting family. The people I saw every day were my students.

From that relationship, the classroom project emerged, but I did not know it was art. Each class lasted one hour: 8 to 9, 9 to 10, 10 to 11, and so on the next day. Slow, repetitive, almost endless. To endure the monotony, I needed something to make time pass.

It felt like a kind of imprisonment. When you have nothing to do, you invent tasks so the hours move. The classroom became that for me. While the students drew still lifes, I began calling them one by one to photograph them. That was the origin of The Classroom.

As a young teacher, did the weight of authority ever conflict with something internal, a doubt or hesitation? How did that tension shape your images?

Authority is inherent to the classroom in Morocco. The hierarchy is clear, and what the teacher asks is generally done without question. When I began making these images, I was aware of that structure. I asked students to pose, and as long as no one refused, the work continued. The photographs carry the imprint of that dynamic, not as something oppressive but as a reality we all inhabited. The presence of authority becomes part of the composition, a silent force that shapes the gestures, the space, and the relationship between us.

Did you ever feel the need to escape the version of yourself the institution expected you to embody? Did photography open an alternative self-image within that constraint?

Some students were eager to participate and even proposed gestures or variations. I explained that the photographs followed a specific vision, but their enthusiasm mattered. Those who preferred not to pose, I never insisted. You can sense when someone is reluctant, and I always stepped back.

At the same time, I wanted to give space to the few students who clearly had a desire to express themselves beyond the limits of the curriculum. For them, I created a weekly workshop, almost a laboratory. There, the structure shifted completely. I was no longer the teacher. They were the artists, and I was there to support them technically and conceptually. Their projects could last a week, a month, or a year. What mattered was allowing a version of themselves to exist.

When your classroom shifted into a laboratory of gesture and image, at what point did pedagogy become a material you could shape and distort?

In this workshop, I told them that a sheet of drawing paper could be torn instead of drawn on. Tearing was also a form of drawing. It became a space of experimentation. Instead of painting with brushes, they could use branches or stones. This workshop ran parallel to my own work and it slowly dissolved the rigid role of the teacher. Pedagogy itself became a material.

You described these sessions as suspensions of curriculum. What became visible there that the institution itself could never articulate?

The workshop suspended the official program. Students experimented freely and I guided technically when needed. It was a space where imagination overtook instruction, where gestures replaced exercises, and where the institutional order briefly loosened.

In La Salle de Classe, students’ bodies seem to shape the room as much as they inhabit it. Do you see them as co-authors, or as bodies carrying the imprint of the institution?

Their presence shaped the images. Their gestures, their willingness, and even their refusals shaped the emotional space of the series. The vision guiding it remained singular.

You have said the face was never central to your images. How does removing the face reshape the ethics of representation in a society where individuality is rarely affirmed?

I express what I feel through images or painting, and interpretation is open. Covering the face is not meant to impose a symbolic reading; it is simply a way to remove identity. In Morocco, individuality is not foregrounded. One does not say “I want,” but “we want.” Claiming individual desire marks you as different, and difference leads to marginalization. Hiding the face reflects that collective erasure.

When you revisit the classroom now, do you see it as a microcosm of Moroccan society, a condensed stage where collective discipline and contradiction become visible?

You must resemble others, same religion, plans, desires, tastes. Stepping outside the collective norm is frowned upon, even punished. The classroom reproduced this logic precisely. It was a condensed version of the society around it.

Your work often returns to binding: string, posture, geometry. What does binding represent in your images and where do you locate rupture?

My work speaks often of confinement. I cover faces with fabric, cardboard, plastic, materials that obscure expression. The strings that bind or deform the body symbolize the lack of freedom imposed by religion and tradition. We are shaped and sometimes distorted by these forces; we are not fully ourselves.

In Acrobates, the body exceeds physical logic. What becomes visible through distortion that an upright body cannot express?

In Acrobates, I worked with professional acrobats whose job is to contort their bodies. Their suffering is what earns them money; people applaud precisely because their bodies exceed normal limits. It is not dance, where endurance can last an hour. These poses last only seconds, otherwise they cause injury.

I prepared the frame and light, asked them to perform the distortion and captured two or three images before they returned to a stable state.

I also wanted to show their domestic lives, with family, in intimacy, to reveal the contrast between the spectacle and the difficult social backgrounds from which they come.

Do you believe freedom can exist inside an institution or is it always partial?

In Morocco, as in many countries, people believe total freedom does not exist. The teacher-student dynamic of the 1980s has evolved; today’s children communicate differently and institutions have shifted. But the broader truth remains: the human being is imprisoned in this world from birth to death. Freedom is always partial.

Your images often point to forms of social stagnation. When you construct a visual concept, what vision of society are you choosing to bring into focus?

A concept, for me, is simply an idea. For instance, death. I might show a dead society, one that no longer moves forward, one that stagnates. When I represent society, I sometimes choose to show it as inert, unmoving. This, is the core beneath.

In order of appearance

- Hicham Benohoud, La Salle de Classe, Series, 1994-2000, Marrakech, Morocco

- Hicham Benohoud, Acrobatie, Series 2017, Marrakech, Morocco

- Hicham Benohoud, Acrobatie, Series 2017, Marrakech, Morocco

- Hicham Benohoud, La Salle de Classe, Series, 1994-2000, Marrakech, Morocco

- Hicham Benohoud, La Salle de Classe, Series, 1994-2000, Marrakech, Morocco

- Hicham Benohoud, La Salle de Classe, Series, 1994-2000, Marrakech, Morocco

- Hicham Benohoud, Acrobatie, Series 2017, Marrakech, Morocco