(AB)NORMAL

Architecture as a living process: world-building beyond the normal

Founded in 2018 by a group of collaborators, Mattia Inselvini, Davide Masserini and Luigi Savio, driven by a fascination with obsolete technologies, gaming culture, and ephemeral atmospheres, (AB)NORMAL studio began as a shared diary of colorful renderings and narrative experiments rather than a conventional architecture firm. Over time, these graphic explorations evolved into three-dimensional environments, from temporary installations and exhibition spaces to commissioned architecture, where the virtual and the tangible, the personal and the collective, converge. NR spoke with the architectural studio to trace the origins of its practice, its interdisciplinary approach, and the evolving philosophy that positions architecture as a living, inhabitable process.

I would love to begin at the origin of your practice. When we met, you showed me your early rendering drawings, where you used color gradings to create imaginative words and utopy spaces. Your website also presents sections of sketches, graphic novels, and research projects across diverse formats. How did these explorations evolve into the construction of three-dimensional, inhabitable space, and how do you conceive interdisciplinarity within your practice, particularly the relationship between image, narrative, research, and built form?

(AB)NORMAL began in 2018 as a shared diary rather than a studio in the conventional sense. We were collecting formal obsessions and reflections on contemporary life—together with a fascination for obsolete technology, gaming culture, and a certain kind of spirituality. Producing images was almost a form of collective therapy: a way to exorcize the fantasies that tend to cling to the creative process.

Those early renderings, with their gradients and artificial atmospheres, were not meant to represent architecture. They were small world-building devices. Plants, statues, iPods, headphones, joysticks, fragments of architecture, and 3D graphic elements became protagonists of collages that were trying to capture emotions, historical moments, and personal reflections. We often used architectural representation tools inefficiently on purpose – because for us the “error,” the glitch, the excess, was part of the thinking.

Over time, what was initially graphic started to reveal a spatial potential. We realized that the narrative quality embedded in the images could become operational in three dimensions. That’s how we moved into ephemeral environments, exhibitions, fashion shows, and temporary installations: spaces conceived as portals where the boundary between the virtual and the tangible becomes softer, and where digital culture can be experienced collectively, in public space, rather than privately on a screen.

Interdisciplinarity, in our practice, is not about blending disciplines as a stylistic choice. It’s a natural condition – an open system where formats constantly translate into each other. Image generates atmospheres and iconographies; narrative gives time, causality, and social behavior; research adds friction, specificity, and a reading of contemporary cultural phenomena; and built form is where everything becomes measurable, negotiated with gravity, budgets, regulations, and bodies.

We don’t see a separation between thinking and construction, between theory and space. Architecture is not a final object for us, but a living process: a way to transform research into concrete experience, and to make the complexity of the present spatial, inhabitable, and shared.

Your work conveys an approach to architecture as the shaping of time, space, and human experience rather than the mere production of aesthetic environments. It evokes, for me, a sensibility reminiscent of Bachelard’s phenomenology, attentive to how spaces are experienced and how time is woven into them. In developing a project, do you start by asking who the space is meant for, or what it needs to feel like? Beyond these immediate considerations, do social, political, or theoretical reflections on inhabitation and identity play a role in how you conceive and compose your spaces?

I’m glad you mention Bachelard, because that attention to lived experience resonates with how we work, although we rarely start from a theoretical framework in a direct way. We begin from a more immediate question: what kind of atmosphere should this space produce, and what kinds of behaviours should it enable?

In many projects we don’t separate “who the space is for” from “what it needs to feel like.” We start by mapping a set of bodies, rhythms, and expectations, the clients, the visitors, the workers, the public, and at the same time we try to define an atmosphere, an emotional disposition. For us, architecture is not only a form, but a temporal condition: a sequence of thresholds, pauses, intensities, and moments of orientation or disorientation. Especially in ephemeral environments, what matters is not the object, but the experience of moving through it and the way people recognize themselves inside it.

The composition of space, then, becomes a way to organize time collectively: light, sound, images, materials, and interfaces are not decorative layers, but tools to construct a shared situation. This is also where the virtual and the tangible matter to us – not as a celebration of technology, but as a way to compress distances and create a feeling of proximity between people, even when they come from different worlds.

Social and cultural reflections are always present, because we constantly observe contemporary phenomena – from gaming to streaming, from entertainment to the aesthetics of technology – and we try to translate those into spatial experiences. We are careful not to use our work as a platform for explicit political statements, but inhabitation is never neutral. Choices about openness, accessibility, visibility, and flexibility always imply a position.

So rather than starting from an ideology, we start from the reality of the present, and we try to build spaces where contemporary identities and forms of coexistence can be rehearsed, not just represented.

Looking at some of your past projects, such as your graphic-novel explorations, there seems to be a consistent interest in the interplay between narrative, spatial sequences, and materiality. How do these non-commissioned or experimental works inform your approach to commissioned architecture? Would you say these projects operate as laboratories for concepts, atmospheres, and techniques that later manifest in built spaces ?

Narrative is central in these experiments because it forces space to unfold in time. A graphic novel, for instance, is already a spatial tool: it’s made of sequences, thresholds, cuts, pauses, and intensities, which are exactly the ingredients of architectural experience. Through these formats we can prototype how a space might be inhabited, how a body moves, what kind of attention or distraction it produces, and what kind of collective situation it enables.

Materiality also enters early, even when the work is virtual. We use digital tools not to “illustrate” a final design, but as an operational environment where we simulate light, textures, reflections, and spatial compression. In that sense, the rendering becomes a critical device — a way of thinking through material behavior before it becomes construction.

When we move into commissioned work, those experiments don’t simply provide a catalogue of aesthetics to apply. They provide a vocabulary of techniques and questions: how to build a Stimmung, how to design a space as a flexible infrastructure, how to combine physical elements with image, sound, and interfaces, how to accept the productive role of error, and how to make the experience collective rather than purely visual.

So yes, they function as laboratories, and simultaneously, as a constant training ground. They keep the practice open, and they prevent architecture from becoming a fixed style or a formula.

Materials appear as active agents in your practice, with intrinsic behaviours, textures, and narrative potential. To what extent does material research guide your design process, and in what ways is matter treated as a conceptual partner, as a vessel of memory, or as a means to articulate spatial and sensory qualities?

Material research entered our work progressively, growing in importance as our projects became more spatial and inhabitable. At first, materials were part of an image vocabulary, linked to atmosphere and iconography. Over time, we began to treat matter as an active agent within the design process. Materials carry behaviors, react to light, define acoustic conditions, age, reflect, and absorb, producing an immediate emotional and cultural reading.

Because our practice moves between the virtual and the physical, we test material atmospheres early through digital simulations. Rendering becomes an operational environment where texture, reflectivity, depth, and spatial compression can be explored through iteration and error. This allows materiality to guide decisions long before construction.

Matter also acts as a vessel of memory. Certain surfaces evoke domestic familiarity, industrial systems, or obsolete technologies, triggering recognition and affect. In this way, materials become conceptual partners in composing an atmosphere. Ultimately, material choices articulate sensory qualities such as warmth, opacity, intimacy, and exposure, shaping how time is experienced in space and how people inhabit it.

Your practice also extends to the design of objects, such as tables or other design elements. When approaching these smaller-scale pieces, how does your method differ from designing larger spatial environments? To what extent do considerations of the surrounding space, function, and human interaction inform these objects, and how does your approach engage with notions of decoration or ornament within the broader logic of the project?

We approach objects almost the same way we approach architecture. Even at a smaller scale, we design them as spatial devices rather than accessories. A table, a lamp, or a custom element is treated as a unique piece with its own presence, geometry, and narrative potential, like a small building inhabited through use.

The main difference is intimacy. Objects are experienced at close range and through contact, so function and human interaction become immediate. We think about posture, touch, weight, and how bodies gather around an object. We also consider the surrounding space. We rarely design standalone pieces. We imagine objects as part of an ecosystem for the whole space, shaping how a room is used, how circulation works, and how attention is directed.

Decoration and ornament are never applied superficially. What might appear ornamental is often structural or performative. Detail, texture, and material behavior reinforce the project logic and intensify atmosphere. An object can become a threshold, a marker, a focal point, or a small ritual.

I would like to discuss your most recent project, which stands out in the portfolio of works made so far: the creation of a custom sound system for WSA NYC. How did this commission come about? Considering WSA is described as a spatial platform blending architecture, design, exhibitions, and brand-driven environments, what was the initial brief or cultural ambition behind this collaboration? Did it originate as a product-design assignment, an installation, or an attempt to rethink what a space for music, art, and social gathering could be in New York?

The request wasn’t simply to “deliver a product,” but to develop a custom sound system that could act as an identity element and a piece of architecture in its own right. From the beginning, we understood it as a project about atmosphere, behavior, and gathering, as much as acoustics.

Rather than starting from a conventional hi-fi object, we worked as we would on an architectural commission. We considered the surrounding space, how people move, where they pause, how they socialize, and how music performs within that context. The goal was to create a system that supports different modes of inhabitation, from focused listening to informal conversation, without turning sound into background decoration.

So the project sits somewhere between product design and installation. It is a unique object, but it also reorganizes the room and amplifies the cultural ambition of WSA: to rethink the space of music, art, and social life in New York as a shared environment, where technology becomes part of the spatial narrative.

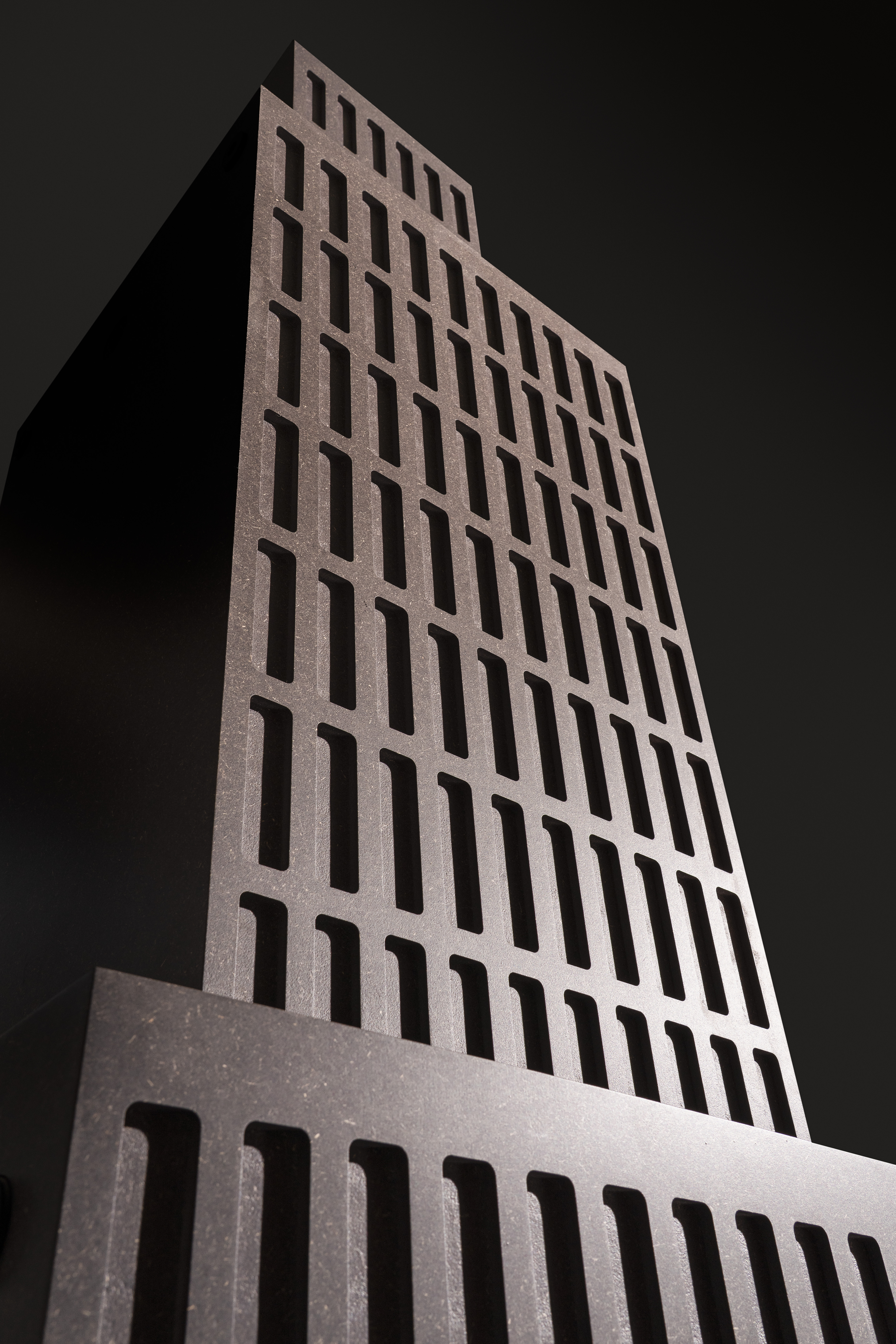

The WSA Sound system is presented not as a mere sound setup but as a sculptural constellation of speaker-towers whose modular design echoes rigid geometry and corporate aesthetics. In designing this, how did you negotiate between its identity as a functional sound system and as an architectural-sculptural installation? Explaining myself clearly: looking at it, it reads almost as a miniature city in itself, with its own carefully drafted colors and shapes. Could you use this project as an example to discuss how aesthetics, function, and conceptual intention intersect in your work? How do these dimensions inform each other in the design process?

Yes, the WSA system is a good example of how function, aesthetics, and conceptual intention intersect in our work, because we designed it as an architectural landscape rather than as audio equipment. We began from performance and presence. The system had to work acoustically, but it also had to occupy the room and become readable as a spatial structure.In our practice we manipulate the scale of objects to create spatial tension. When a speaker tower becomes as tall as a person, or when a subwoofer becomes a block, the object stops behaving like a device and starts behaving like architecture. It produces orientation, distances, and thresholds. It changes how you enter, where you stand, how you gather, and how you look. In the image, the constellation reads almost like a miniature city because the pieces have the logic of buildings. They create a skyline, bases, voids, and a rhythm of volumes distributed across the room.

This sensibility comes from our early work and from narrative formats such as the graphic novel. Working with sequences trained us to think in terms of framing and perceptual displacement. Exaggerating scale creates that displacement. It makes the familiar slightly uncanny, shifting the experience from pure utility toward something closer to an artistic encounter.

The rigid geometries and calibrated colors reinforce that dual identity. They give the system an infrastructural, corporate aura, while allowing it to function as a sculptural installation that organizes both sound and space.

Considering the diversity and conceptual depth of your work, what open territories remain for future investigation and experimentation?

We honestly don’t know, and we prefer it that way. We try not to define future territories too precisely, because the most valuable directions often arrive as surprises. What keeps the practice alive is lateral thinking: the ability to move sideways across disciplines, scales, and formats, following unexpected connections. New collaborators, new technologies, or new cultural phenomena can suddenly open territories we couldn’t have planned. Staying open to that uncertainty is what generates enthusiasm and keeps our work from becoming a fixed style or a predictable agenda.

I would like to conclude our conversation by returning to the very origin of your practice: the choice of your name. Naming a studio is never a neutral act; it often contains the initial spark that motivates its existence. After everything we’ve discussed, I am curious to hear how this origin resonates throughout your work. Why Abnormal?

Abnormal has a very literal origin, and a broader meaning that has stayed with us. The studio began as a graphic reflection on architectural representation. We were working with 3D tools and we became fascinated by the gradient of a normal map, the image that encodes surface orientation through RGB colors to simulate depth and light. That technical vocabulary, and that strange artificial “skin” of digital representation, became part of our identity. It marked the moment when our practice was more about generating worlds through images than producing buildings.

Over time, the name also became a statement about attitude. Many of the projects we do try to go beyond what is considered normal within architecture and design. We look for iconicity and uniqueness, for forms and atmospheres that feel slightly displaced, excessive, or unexpected. In that sense, “abnormal” is not about being strange for its own sake. It is about refusing a standard formula, keeping the practice open, and allowing each project to find its own language, even when it pushes beyond familiar categories.