Domenico Gnoli

“I never actively mediate against the object, I experience the magic of its presence”

As one enters the exhibit – the soft stumps of the shoes break the silence – the first instinct is to graze the fingers over the relics of Domenico Gnoli, to violate the laws Fondazione Prada upholds just to caress the paintings on display and test their hyperrealism. As the sensation passes, a new emotion washes over: the awareness of stepping into someone’s home and looking into their private lives, becoming an insider and an outsider at the same time. The artist may not have intended to cause such an emotion, but there it is in its youthful peak. From the shadow clothing over the fabrics and wave-like curls of the hair to the figures sleeping under the sheets, Domenico Gnoli mastered narrating the everyday life everyone tries to hide.

Fondazione Prada presents the exhibition “Domenico Gnoli” in Milan from 28 October 2021 to 27 February 2022. This retrospective forms part of the series of exhibitions that Fondazione Prada has dedicated to artists – such as Edward Kienholz, Leon Golub, and William Copley – whose practice developed along paths and interests that took a different direction from the main artistic trends of the second half of the 20th century. The exhibit marks an exploration of Gnoli’s practice within a discourse free from labels and documenting the international cultural scene of his time, all while understanding his art’s contemporary visual relevance and recognizing the inspiration he drew from the Renaissance to illustrate the value of his works.

Conceived by Germano Celant, the exhibition brings together over 100 works produced by the artist between 1949 and 1969 and will be complemented by as many drawings. A chronological and documentary section featuring materials, photographs, and other items will retrace the biography and artistic career of Domenico Gnoli (Rome, 1933 – New York, 1970) more than fifty years after his death. The project has been realized in collaboration with the artist’s Archives in Rome and Mallorca, which preserve Gnoli’s personal and professional heritage.

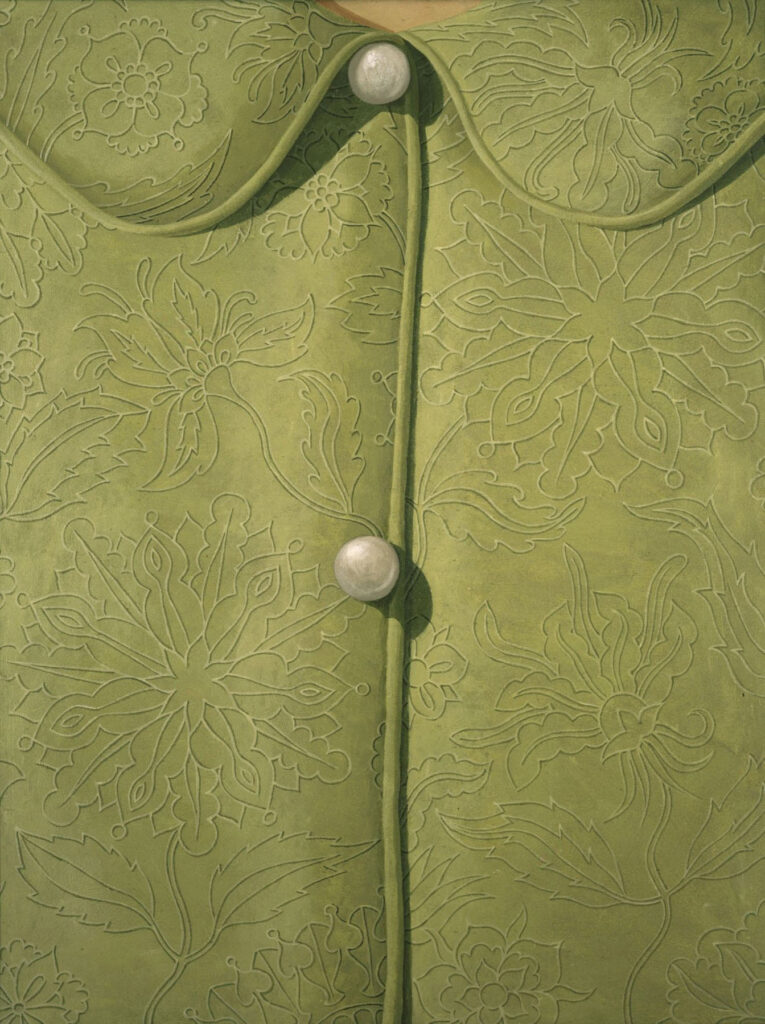

A homeowner touring a sojourner in his abode encompasses the arrangement of Gnoli’s artworks at Fondazione Prada. The yellow seat covers form uniform patterns, so freshly washed and pressed for an elegant dinner party that Santiago Martin-El Viti – based on Gnoli’s portrait of him sitting in one of the sofas – would attend. A beige shirt soon appears on a yellow tablecloth with silhouettes of flora in green, the creases and folds of the shirt visible even without scrutinizing the painting. From the living room, Gnoli heads towards the bathroom where an empty bathtub awaits next to a branch of a cactus that adorns the minimalistic interior.

Author: Domenico Gnoli (1933-1970) Title: APPLE Date: 1968, signed and dated on the reverse Dimensions: 117 x 158 cm Medium: Acrylic and sand on canvas Inscriptions: on the reverse inscribed by Domenico Gnoli: D. Gnoli 1968 ” apple ” (1,60 x 1,20) Inv. Fundación Yannick y Ben Jakober no.51 Fundación Yannick y Ben Jakober

“Many things have changed for me: I finally feel I have shrugged off many constraints and prejudices,” Gnoli wrote in 1963 and a letter to his mother. “I paint as I feel without worrying about the current culture and my responsibilities towards it and I intend to live the same way: free and faithful only to the truth that I feel now. Life begins now; up to this moment I have been apprehensive of too many things: school, friends, modern painting, socialism, marriage, culture, maturity, responsibility. I have painted a whole load of imaginary characters: a large woman reading the newspaper, a gentleman peeing against a tree, an office worker, a poetic waiter with blue lips, and then numerous portraits, but with a difference: instead of people seen from the front, they are seen from behind. Because, I thought to myself, mountains are painted from every side and so are houses, flowers, animals, trees: everything. Men and women are not, however. They are the exceptions and are only painted frontally, in three-quarter profile or from the side. Why?”

Down the hall, guests find the elevator that will take them up to the private spaces of Gnoli’s home. As the doors open and the bell dings, they stumble upon the guestrooms where intoxicated guests may sink into one of the well-made beds. All the beds are available except the ones where Gnoli and a woman sleep. In a couple of his paintings, they break up and make up in a span of two canvases, implied by the joined and separated figures under the sheets that Gnoli’s art style highlighted.

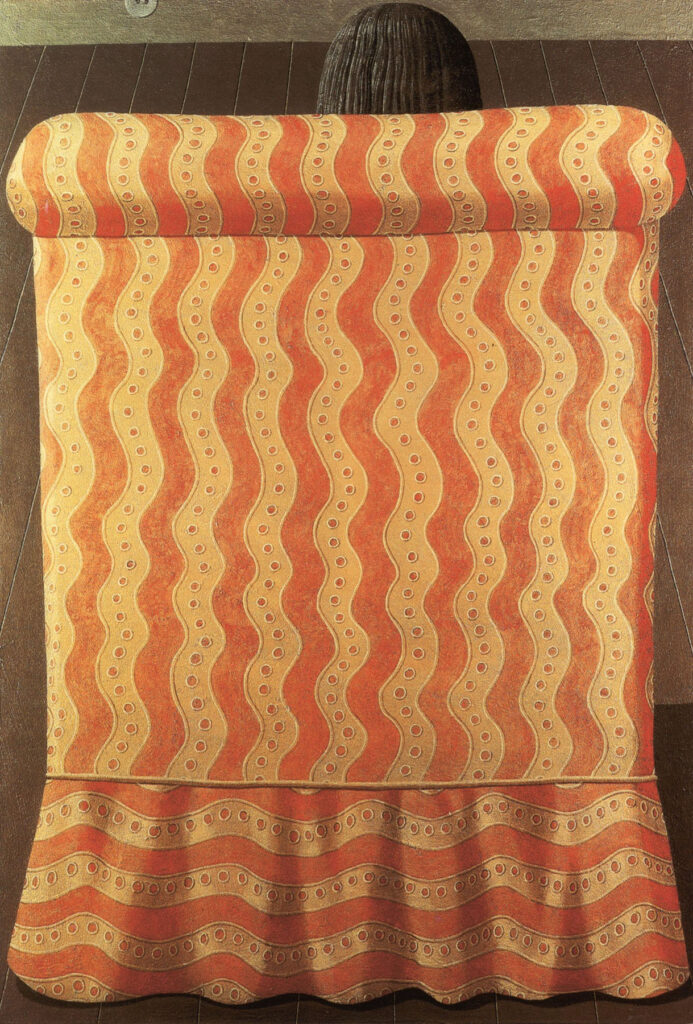

Author: Domenico Gnoli (1933-1970) Title: CURL Title during the exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery, even though it does not appear on the catalogue this painting was exhibited Date: 1969, painted in s’Estaca, Majorca, October 1969, last paining painted by D.G. Dimensions: 139 x 120 cm Medium: Acrylic and sand on canvas Inv. Foundation C. no. p23 Courtesy Fundación Yannick y Ben Jakober

From the exhibit’s text: “For many years Gnoli’s work was interpreted in relation to the forms of realism that arose in stark contrast to the abstract and conceptual currents of the 20th century. Gnoli was viewed as a pop or hyperrealist artist by contemporary critics, who nevertheless recognized the peculiarity of his poetic imagery and artistic production. Over the following years, art critics drove their attention to those paintings made from 1964, characterized by a photographic cut and a specific interest in the human figure and objects, acknowledging the inspiration that he drew from the Renaissance or underscoring his ability to create paintings capable of creating a dialogue with the observer.”

The connection between Gnoli and the viewers sizzles, the manifestation of the intended dialogue. From one alley to another, the transition in storytelling simmers in the next paintings. The house party is about to begin. The noise of the invited crowd on the ground floor filters through the master bedroom where Gnoli and the woman deck up. The private and public lives start to blur the more the viewers wander around to gaze at Gnoli’s paintings.

On his canvases, the selection of hairstyles – neck-length, braided, and curled – comes first before choosing the shoes to wear for the party – flats or heels, leather or synthetic. Next up, Gnoli’s artworks zoom into the details of the clothing to don: the folds of the shirts’ collars, the pearl buttons of the dresses, and the zippers of jackets. Almost ready, the artworks display a necktie and a bowtie, both in stripes, and an ironed suit with a pocket square. Gnoli and the woman close their bedroom door and head for the elevator, a huff to expel the breath of excitement and agitation before inquiring “Ready?”

In 1965, Gnoli expressed how he had always embodied his art practice, but it did not attract attention due to the abstraction’s moment. “I have never even wanted to deform: I isolate and represent. My themes come from the world around me, familiar situations, everyday life; because I never actively mediate against the object, I experience the magic of its presence,” he commented. Only then, thanks to Pop Art, that his paintings became comprehensible, the employment of simple, given elements that he neither amplified nor reduced.

Three years later, the artist deemed his system as a vehicle of showing two scenarios in one space. “You begin looking at things, and they look just fine, as normal as ever; but then you look for a while longer and your feelings get involved and they begin changing things for you and they go on and on until you don’t see the house any longer, you only see them, I mean your feelings,” he penned. “For instance, take some of these modern pictures where nobody can tell what’s what; they are a mess because they only represent the feelings rumbling about without giving you any idea of why it happened.” At Fondazione Prada, Domenico Gnoli welcomes the viewers into his home and hands them an invitation to reminisce the legacies he left.