Haley Josephs

Glowing Underfoot

Painting is not easy. In fact, “It’s hard to make paintings”, says Haley Josephs. (A painter.) Josephs is not wrong. Art is old. It has survived time and has broken ground longer than civilization. From the Kununurra petroglyphs in Australia to the Chauvet Caves and Fayum mummy portraits, art has grown old, and painting has grown up. But it has never been easy. No matter how ‘simple’ Matisse made his forms, there is more than just technical skill required to paint something that endures. Although modern stresses spread on the contemporary skyline, art and creation are myriad and many.

Some people paint humanity in its barren reality, while others depict the trees and the abstract emotions of humankind. Some grow grass and paint horizons that are endless and gold or muted in a haze. And some people paint both.

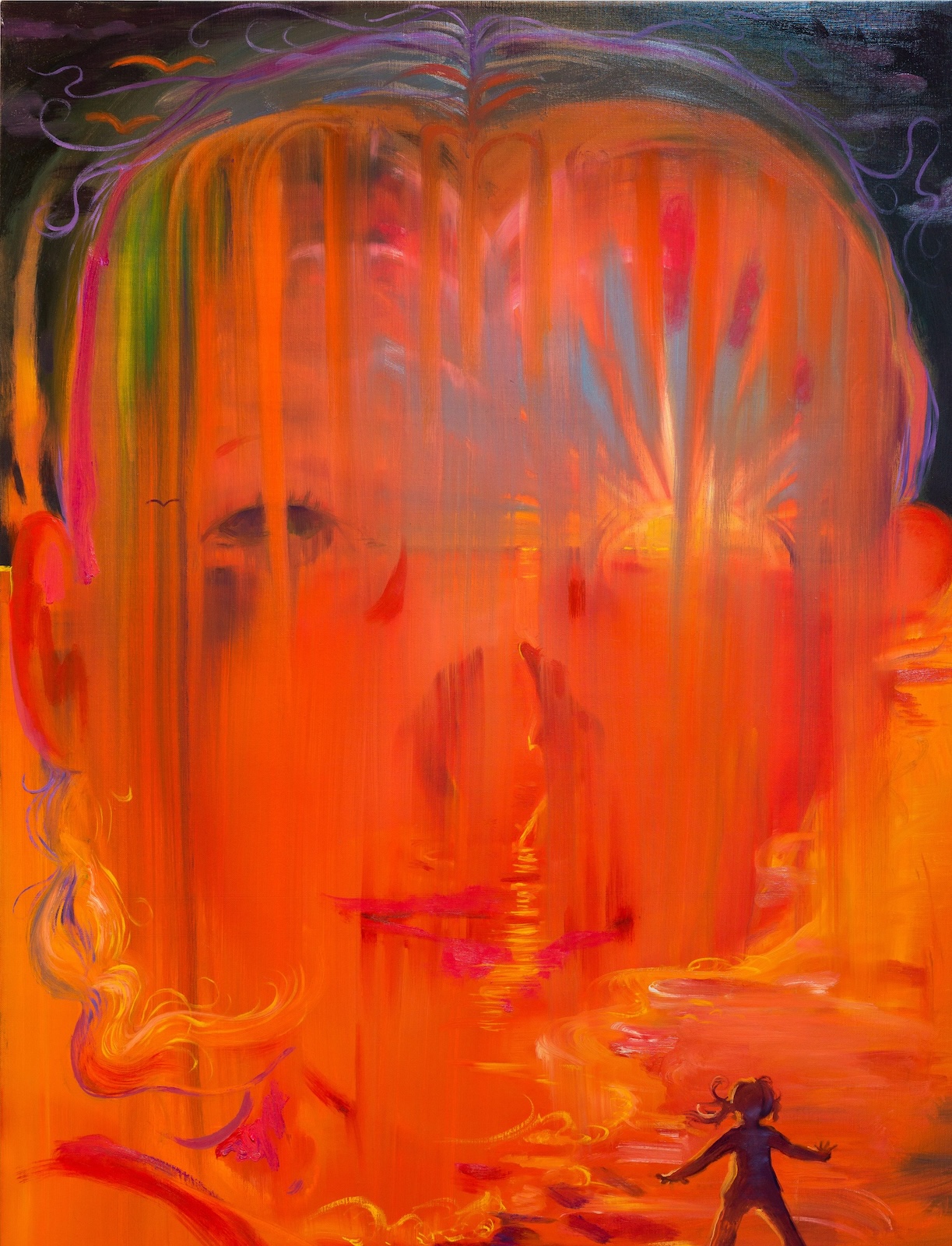

Haley Josephs paints atmospheres stratified by living forms and forests. Look at the paintings long enough, and the figures and shrubbery sway, form into forest and producing form. They are separated by time and depicted in a scene. Superimposed by a colour that glows from afar like hot fire or heavy foreboding, soon to reach but still at a distance. Intimately separated by layers of paint and the glazes that hold them. Josephs shares emotional figures that come with a sense of accepted loss. They radiate mystical serenity.

Her paintings give us something to ponder on, to feel. They shed light and emotion like myths and time, spreading out into the present like glowing bulbs in a century that is gloomy and dark, somewhat starved of and simultaneously surfeited with hope.

With a pictorial attitude that runs along the lines of an “If I don’t do it, then it won’t get done, so only I can do it” attitude, Josephs discusses her work and how she mines her mind, constantly experimenting — and at times failing — in a drawn-out process to improve and develop more and more work. When she will be done is unclear. Actually, the answer is clear. She won’t. She has a lot of work to do and isn’t stopping anytime soon.

Billy De Luca: Where are we calling from now?

Haley Josephs: Just home in Brooklyn. My studio is nearby in Williamsburg, but I’m around Domino Park next to the East River.

Billy De Luca: The last time you exhibited your work was at the tail end of last year. How did you feel about that show in London?

Haley Josephs: I feel like so much has happened since that show, but it really set me up for where I’m at now. Having made so many works with such intense colours from my time in and around Acadia National Park really helped me feel free. I learned a lot from all the explorations of colour, the references to nature, and even just being up there, honing in.

Billy De Luca: And what are you doing now?

Haley Josephs: The work has been progressing into a darker territory. The show gave me the nutrition to keep going; many of the exhibition’s works were made out in nature. I made a lot for that show, and I could have kept going. I just felt this need to produce. There was just so much to do, even though there was less time and space. It was the most I’ve ever felt OK about a show; I always feel pretty weird about putting all this emotion into something and putting it out into the world and having people watch you. But this show, I felt the calmest. I used to be very judgemental of myself after a show, but after the London exhibition, I felt ready to move on to the next step.

Billy De Luca: And now that this exhibition is done, what would the ‘next steps’ be?

Haley Josephs: I used to be interested in the lusciousness of paint right out of the tube or barely mixed on the canvas, letting that be and sit on the surface. I thought that was really sexy. Now, I feel like there’s more nutrition in delving into how to capture colours in a shadow. I want to spend more time on the paintings I’m currently working on. I want to be layering more, practicing with different glazes, and working on the complexities of deeper colours. Finding colour within the darkness.

Billy De Luca: The darker tones reflect light when glazed, and it’s a fascinating experience up close. When you look at a Caravaggio, you can see how much layering goes into his dark background and how many colours sit behind this ‘darkness’.

Haley Josephs: And it’s attractive. When I was in London for my show, I also explored parts of Europe over the weeks. I realised that when I was surrounded by paintings in museums, I was attracted to those with darker tones. Before, I felt intimidated to push through and challenge colour. But now I am more interested in the browns, greys, and greens that have these complexities.

Billy De Luca: How do you achieve that?

Haley Josephs: I’m now using a material called Canada balsam (a natural resin that has the effect of an old master’s glaze). They almost look like there are colours underneath glass, layered so much and keeping the vibrancy without muddying it. When I go up close to a painting, I like to see what the artist was thinking about, like how tree bark is expressed through the paint, not just colour. There’s this one painting I did with a Unicorn, and it had an extremely glossy surface, so much so that when you look at the painting in person, your body is also in the image. It’s almost like a mirror, and you have to confront being a part of the painting and interacting with it. That’s also why seeing the picture in person and not just online is essential.

Billy De Luca: What sort of dialogue arises from your work?

Haley Josephs: Well, I think the truth is my work is really hard to talk about. I think of paintings as metaphors and try to create worlds of emotional landscapes. There’s this surreal aspect because it’s so otherworldly. Sometimes the landscape or sky or abstract landscape is supposed to represent this inner world, one where people get this intensity of emotions that are unnamable.

Like everything is sort of unnamable.

Billy De Luca: It can only ever be boxed into a word…

Haley Josephs: And that’s why I make paintings. It’s my way of communicating, some people can say things in words, but obviously, not everybody can articulate everything. I can only hint at certain things that it’s about. It is up to the viewer to feel how they feel; that doesn’t have to be described in words.

Billy De Luca: How do you feel about these works?

Haley Josephs: I mean, to be honest, this work feels like me. More like what I’ve been trying to describe in the past. I feel like I came up short before and couldn’t really tell you what I was trying to tell you. However, with this recent show, I felt closer. The works I’m making now are more ethereal and feel less about the figure and more about emotion. It’s not always just about narrative. People notice there’s a greater intensity to the work. Maybe it’s because of the shift in a darker palette, but I think it has to do with me being more intentional about how I start my compositions and what means I used to execute the work. In the past, I would let myself be more content with things and think, ‘Oh, this is OK,’ and wouldn’t really question everything in a way that I felt like I was really challenging myself. But I am now.

Billy De Luca: Have you changed your practice method?

Haley Josephs: I used to use source materials, sometimes taking photos of myself to get the anatomy right or looking up pictures online to inform my vision. Now everything comes from my imagination. I’ll draw out a composition in my sketchbook, letting it come out onto paper. Making sure I have the correct design is just as hard. I just draw it out until I get it. It’s now coming from this true place and looking how I really wanted it to look.

Billy De Luca: That’s very much like Giacometti’s visible reworkings in painting. Fleshing it out shows how hard painting and proportion can really be. When did you start working in that way?

Haley Josephs: When it came to school, I mainly painted from photographs of family members. I liked older photos (there’s something interesting about the colours of older photographs), I liked the palette, and I then started working on pictures of female family members that had passed on. My sister and my aunt passed on, and they sort of became characters that naturally came up in my work. They inserted themselves organically. When I was using source materials, they’d still be there. Now I’m more intentional about using images in my head. I’ve started doing work that is authentically me, and I’m beginning to rely on my inner narrative and imagery. I have to hone in on that.

Billy De Luca: When did you begin making art in general?

Haley Josephs: I grew up attending a Waldorf school (Steiner School) with a huge emphasis on art. We did a lot of watercolours and form drawing — and a lot of the prompts were biblical. But before then it starts with a memory. I was four or five years old, and my cousin (Sophie) and I lived together for a little while. We had a basket filled with old crayons and scrap paper, and we would draw all day for hours. We used to get really into this thing where Sophie would take all the neon-coloured crayons, and we would try to invent a new colour. We would draw one layer after another with these neon crayons. They would build up on top of each other, and I would have this feeling in my stomach that made me feel tingly. I wanted to get this…colour experience. It felt like a trip, like I was in this other world, and I realised that, through drawings, I could make this different world. A lot of kids, when they grow up in challenging situations, can interact and react very differently. Drawing this other world allowed me to escape.

Billy De Luca: And the landscapes? With these paintings, there is less immersion in nature — it almost pushes back. Are these backgrounds reflecting a sense of longing?

Haley Josephs: I think I was very much influenced by my time in Maine. I was excited to be painting so much, diving into that sense of movement and place and the inner world, the emotional landscape of the characters. Sometimes, however, the paintings are done in a more abstract way, but still holding to representation and having this dream world be real but fantastical. Not everything has to be recognisable.

The landscapes are also a part of the symbolism in my work. They revolve around my aunt. When I was a kid, she went missing and was in this accident in Montana and walked off into the wilderness and was never found. It has a very specific image in my head of this woman walking off into the Montana landscape, filled with rolling hills and a big sky. When I was at art school getting more into my specific style, I kept painting this scene with a woman and this landscape in her head and then outside of her because I imagined her disappearing into the horizon. Sure, the characters in my work can have this sadness, but the image also sends a message of perseverance and going through difficult times, of overcoming.

Billy De Luca: And do your paintings have a style? One could place a sticker of ‘surrealism’ on a work with melting skies and name anything ‘fantasy’ following an unimaginable scene. But they aren’t only surreal. They are on a canvas and imagined by you…

Haley Josephs: Yeah I mean I have always had a problem with labels, like my whole life. But I think they are probably just paintings.

Yeah. They are paintings.

Billy De Luca: Brilliant. Have you always worked in oils?

Haley Josephs: When I first learned how to paint, it was in acrylic. And being at the Steiner schools, we would paint a lot with watercolour. Watercolour was technically my first experience, but I got hooked on oils, and you can’t go back from oils. It’s just so luscious and. sexy, and I love it. Also, before I went to college, I was really into ceramics and sculpture too, and I still have a sense of clay, but my heart is definitely into paint.

Billy De Luca: And it’s been ten years since you graduated from Art School and got your MFA. Do you feel comfortable with what you are doing now, or are you still exploring the subject matter and changing things?

Haley Josephs: I think from my earlier work being influenced by pictures of my aunt to now, there is a level of looking back which makes me realise it’s kind of always been about this chase. A chase to deal with representing and overcoming as a character, seeing a kind of salvation in different ways. In parts of my life, like after grad school, I got really confused about what my work was supposed to look like. I did a lot of really weird things when experimenting, but I think that’s an important thing to do while you’re there. Trying different things and messing around, and not being so precious about things. It took a lot of reckoning to get through graduating and having your work put in a box. Now, I feel a lot more free, and that’s why the narrative and feelings are still as present as they have always been. But it’s when the work is free that the images and story come out in a more authentic way. Even if it takes a longer time to get there. By making a lot of mistakes and failing a lot, I got to the point of being comfortable with just that, not judging whatever happens. I think the thing that hindered me the most was fear. A fear of expectations of others and myself. Now I feel like I can let go of that, and the absolute truth can then spill out. I’m always there in the paintings, but it got fogged up a lot for a while. It became uncertain. It took a long time, but now I’m breaking free of that.

Billy De Luca: But now, what makes a good artwork?

IHaley Josephs: look for a sense of deep exploration and curiosity. I don’t like settling for something and fitting it into some equation of expectations of what one’s work is supposed to be. If there’s something you want to say, say it, and have a real sense of intention and not be held back by the confinements of style.

I like the idea that art comes from this unknown and trying to say the unnameable. It has to be free; I want to see that there is freedom in the work and that it’s been pushed enough. A good painting is one where you push it out into space — nearly out of control — and then you bring it back down. You have to let it get out of control and then hone it back in. That way, it can capture something that is in this magical realm.

Billy De Luca: And does that mean you know when to stop?

Haley Josephs: I think in the past, I would feel like I wanted the painting to be done in a matter of a day or two, and when I had the composition, the picture would be done (while the paint was still wet). I’d think that’s it. But I stopped too prematurely. Now I’m layering to prolong the painting process. It is getting harder to know when it’s done, but you learn something if you go too far. It’s really nice to have them sitting with me more.

Billy De Luca: I’m sure glazing would help. Titian glazed his paintings up to 20 times back in the day.

Haley Josephs: Glazing, yes! It does so much and shows you how you can think something is done, but then you add another glaze and realise, ‘That’s actually that’s so much better than it was… I did need that when I thought it was done.’ And that’s a big thing to learn. You have to be OK with messing it up. You have to be OK to fail. I like to see paintings that involve a struggle because safety is safe. I think pushing yourself, scaring yourself, and messing with it could be better. Being so precious is not always the answer.

Billy De Luca: There was a recent work you painted that exemplifies this. There is so much depth coming from behind a treelined background, and a glowing filament of yellow light shines past the darkness. Those colours coming through balance with the form on the left, but how are they balanced?

Haley Josephs: Colour is really hard. I wanted there to be this glow, to make them have this luminous quality. I want there to be a sense of glowing from underneath instead of having light on the surface. It also furthers my work as it revolves around this sense of pushing out from underneath. This work aligns more with what I’ve been trying to get out for a long time.

Billy De Luca: It reminds me of a Turner yellow. The luminosity aspect of his paintings also redefines the parameters of how a painting interacts with light. A casual observer could think, “Your old series is bright, and your new series is dark”, but it goes deeper. You are not going from bright to dark. You’re going from bright to luminous. There’s a darkness in front of it, but you can see the light seeping through.

Haley Josephs: That’s what I’m trying to do. It’s super hard to achieve. There’s something about working towards getting that effect that feels like an exploration of the character as well. The character gains a sort of sensibility through a mined inner psychology. The act of layering then feels more appropriate. I’m always learning, even with the glaze I’m working with now.

Billy De Luca: It’s true. There are many aspects in the painting process that are involved in making a painting…and making it glow and making it real.

Haley Josephs: Yeah, it’s about capturing some kind of energy that somebody can react to. The same energy that I felt when I was a kid drawing with those fluorescent crayons, trying to capture colour in this complex way that you have to work towards. And it’s not just one crayon that you can draw with, so the question becomes, how do you find the right grouping?

Billy De Luca: What would you say your harshest criticism of your work would be?

Haley Josephs: There’s always this feeling of being really misunderstood. It’s natural, and it happens a lot. In the past, the work has been talked about in a ‘cutesy’ and ‘pretty’ way and in a less-serious tone. It’s not like the work wasn’t taken seriously, but the subject matter was less regarded because of the emotional femininity of my past work. I went through a whirlwind of emotions, but I ended up with a drive to be more me and push. We all have a unique perspective we all show, so I have to try to show mine and keep going. I have a lot of work to do.

Credits

ENCOUNTER, 2022

BECKONING PATH, 2023

All artworks courtesy of Haley Josephs