Katsu Naito

“People on the edge of society have hidden beauty in their heart”

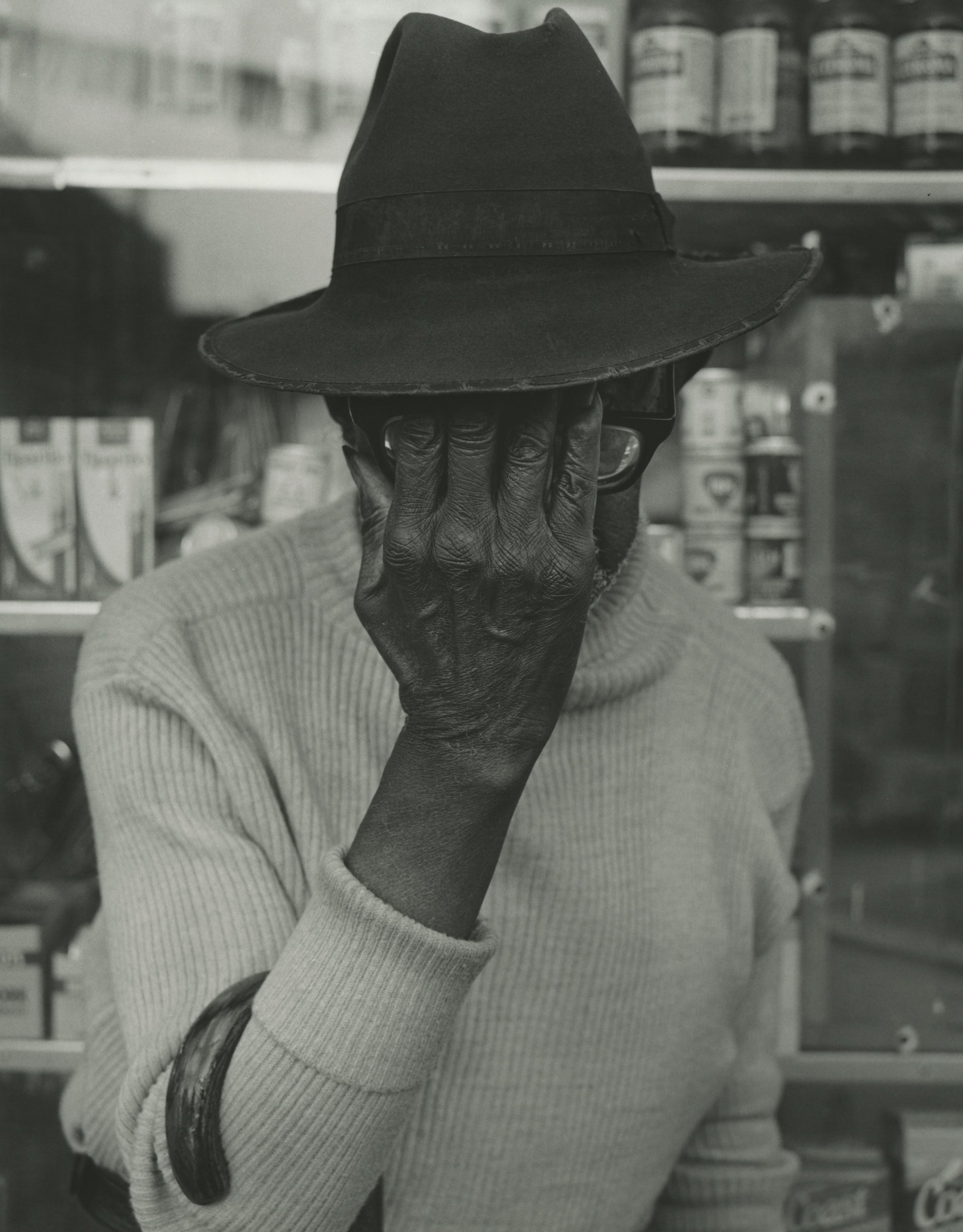

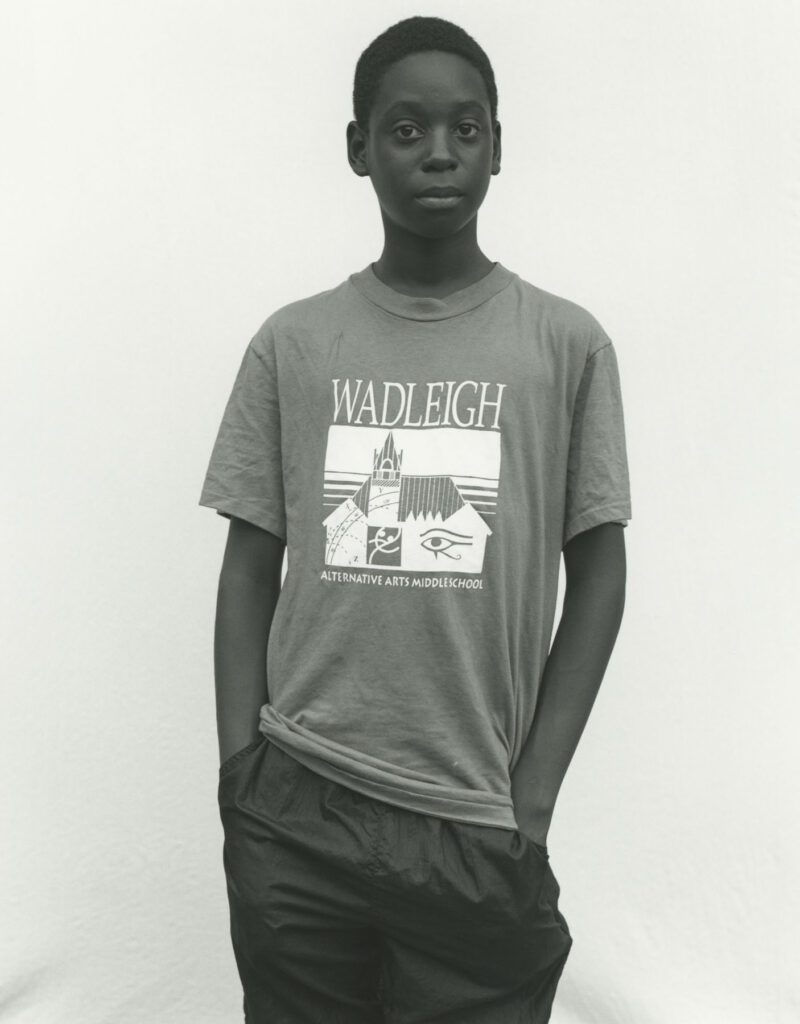

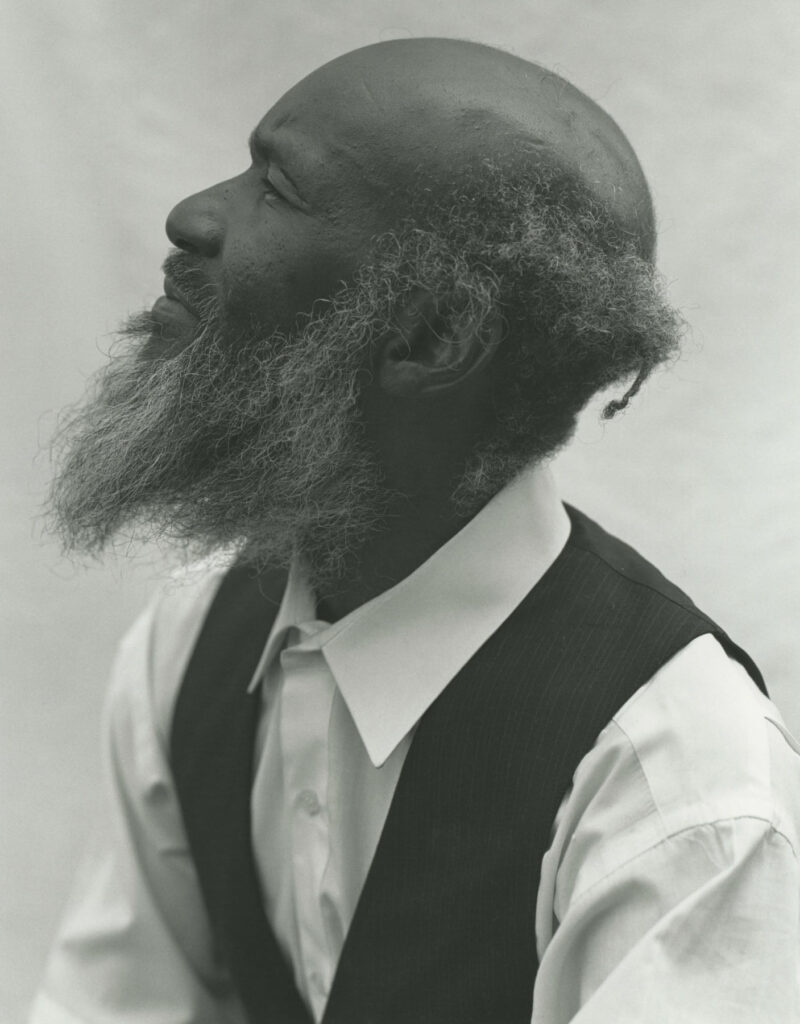

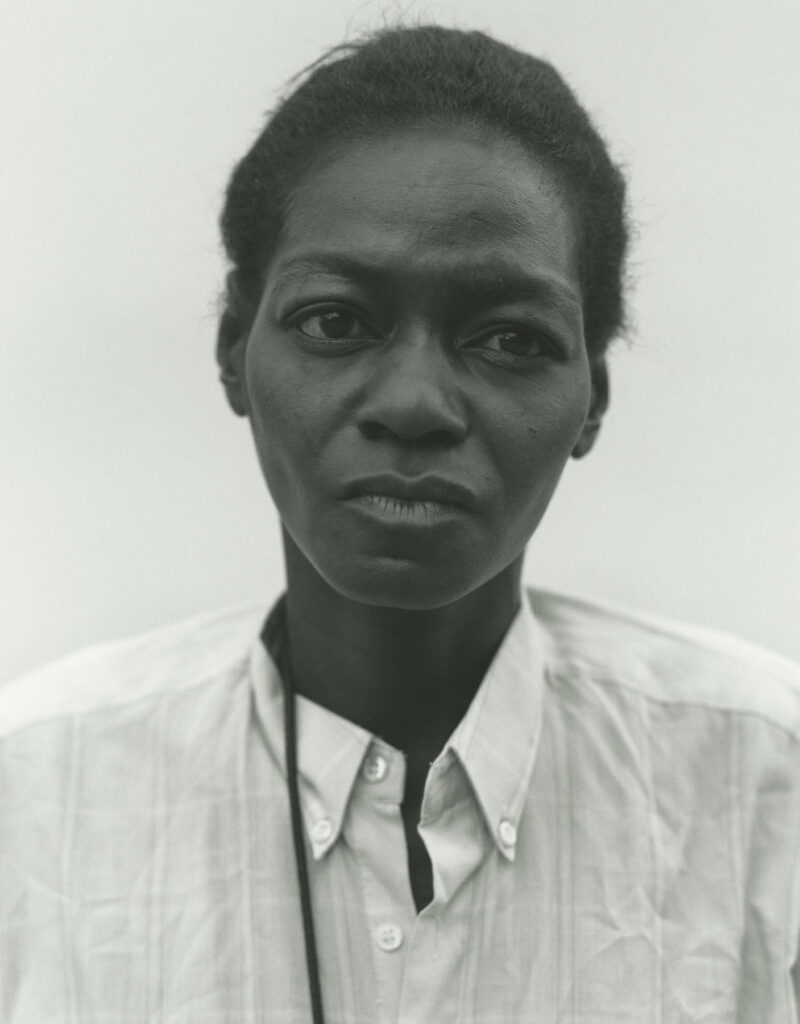

When Katsu Naito arrived in Harlem in 1988, it took him two years before he would begin taking photographs of its residents. It would take him a further twenty years to develop the negatives – a decision he consciously made. The photographer was cautious to build up the trust of the community before pointing his camera in their direction – demonstrating a careful consideration and tenderness that radiates from his work. Sensing that Harlem, which was still recovering from economic devastation from the 1970’s, was in the midst of unprecedented change, his body of work from the nineties offers an insight into a lost neighbourhood. These images make up ‘Once In Harlem’, which captures an extraordinary level of trust between Naito, as photographer and, ultimately, ‘outsider’, and the people who stand in front of his camera. Similarly, the body of work ‘West Side Rendezvous’, published in 2011 but taken around the same time as the Harlem work, evokes the emotive quality that make Naito’s images so compelling. The mutual respect between Naito and his subjects – in this case, transvestite and transsexual prostitutes in New York’s meatpacking district – is timeless, even if the run down backdrops have long been replaced by gentrification. Naito moved to New York from Japan in the mid-1980’s, having secured a job as a chef. Inspired by the street photography of Diane Arbus, a colleague introduced him to his first Leica camera – to this day, Naito explains, he still shots in black and white analogue format.

NR: The photographs from your book ‘Once In Harlem’ are all from the early nineties, but were only recently developed; why did it take so long to develop them, and what surprised you the most from seeing these images for the first time?

Katsu Naito: There were a few reasons it took so long to be published. I worked in Harlem as part of a personal assignment between the late ‘80s and early ‘90s – and I always knew that I wanted it to be published in years to come. Harlem had started to change; towards the end of the ‘80s, abandoned buildings were being given a second lease of life, as parking lots or renovated buildings. I was living through all of this, and I wanted to share these images of Harlem when people had forgotten about it. This was the main reason that I kept the negatives in a box in the corner of my darkroom. I started working towards printing in 2013, going through many test prints in order to find the right quality for the final print – this took a long time.

“I try to put life into the print, as I think it’s important to seal emotional quality into it.”

I really felt the power of photography after printing this series – seeing how these plastic negatives could bring back to life an image after twenty years. As the images started to show in the developing tray, tears dropped onto my cheek, from the surprise.

NR: As a photographer, do you feel it is your responsibility to document the lives of groups of people who can get forgotten amongst society?

KN: I feel strongly about that. People on the edge of society have hidden beauty in their heart, a quality that’s hard to draw out – but it’s something that I wanted to capture with my camera.

NR: Having moved to New York in the 1980s from Japan, did photography give you a sense of control over being in a foreign environment?

KN: Carrying a camera gave me a license to be on the street; it can break language and cultural barriers. It can give control, but I do also believe that it’s necessary to have trust between both parties.

NR: When taking someone’s photograph, what do you look for in their self-presentation?

KN: I only ask the person to stand in front of my camera and communicate through their composure, I often ask myself “how close can I get?”

“There’s a moment of unawareness towards the camera; when I feel that, I start taking photographs.”

NR: What role do the people in your photographs play; are they a part of the composition, or does the act of taking their photo establish a connection with them as a person?

KN: It’s both; the composition and an emotional connection with the person is very important for me. But this must happen in an organic way – a connection with them must come first.

NR: Has the way people respond to being asked to have their photograph taken changed at all over the years?

KN: I don’t expect people to accept my offer of being photographed. In the instances when the answer is no, I wouldn’t chase them for a photograph. This doesn’t happen often though – for some reason almost everyone would say yes to my camera.

NR: As for the way you approach taking a photograph; has that changed over time?

KN: I must be comfortable enough to walk the area. If I’m not comfortable, I can’t make my subject comfortable, so location scouting and understand the atmosphere in the area is the first thing I do. It can take an hour, or months, depending on the project.

“This is the way I have always approached the way I take photographs, ensuring I respect my subjects. This hasn’t changed, and it will never change.”

NR: Why is shooting in black and white important to you?

KN: I only work with black and white film, that I process in my darkroom. It’s necessary to have total control over every step of the process – and I think, most of all, shooting in black and white is the only medium that really emphasises three dimensional reality in a two dimensional format.

NR: What is the most valuable thing you have learnt from taking people’s photograph over the years that you have spent photographing New York?

KN: Living in New York City can be like riding an emotional rollercoaster every day. The fundamental aspect of it, though, is simply the human element.

NR: There is a timeless quality to your work; is this deliberate? And if so, is it a crucial aspect of the photos you take?

KN: Yes. Something that is always on my mind is making photo sessions simple. The person is in front of my camera and they are the main subject. I wouldn’t want to add any meaningless props unless they are already there, and the person has a natural relationship to them. I wanted pull out what they have inside of them.

NR: In terms of having control over an image, how does the process of analogue photography compare with the instantaneousness of digital photography?

KN: There is a quality that I can’t describe with words that can be seen in a gelatin silver print. I often call it “capturing the air”, or “capturing the temperature”. I think it’s is difficult to see this type quality in digital photography.

Credits

Photographs · Katsu Naito from his Once In Harlem series

https://www.katsunaito.com/

Words · Ellie Brown