Squidsoup

“We want people to suspend disbelief, to go with it and experience the work”

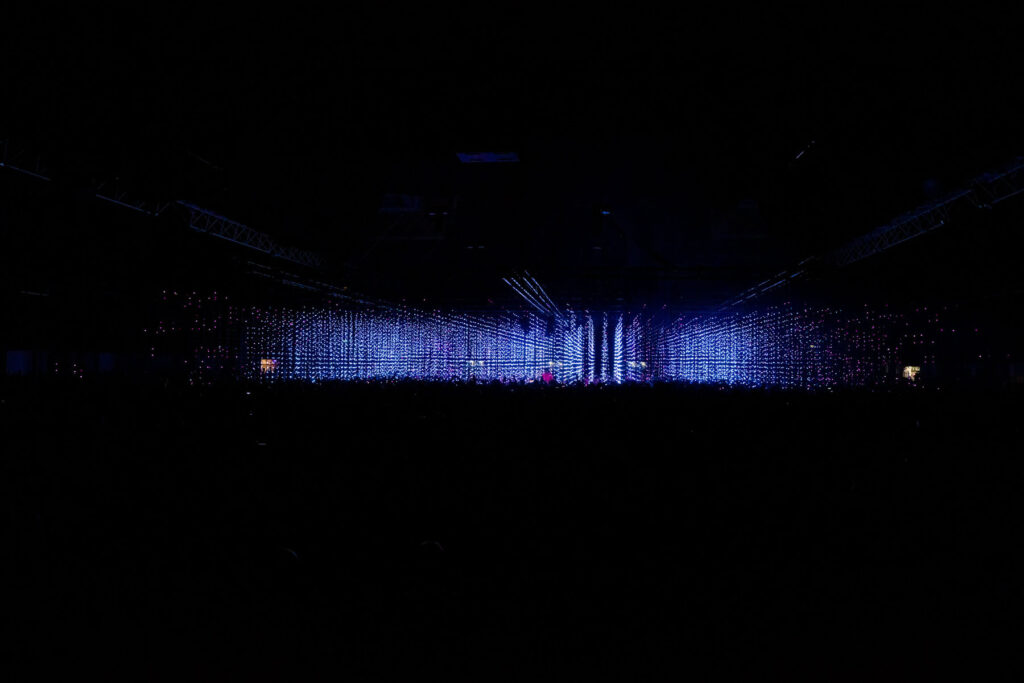

If you saw, or heard about, Four Tet’s string of dates at London’s Alexandra Palace last year, you’ll be familiar with the light installation that immersed the crowd for the duration of each show. The group behind this feat is Squidsoup, whose work for Burning Man in 2018 and again in 2019, you will likely have seen, like those Four Tet performances, via social media – if not in real life. Characteristic of Squidsoup’s work are visually and sensorially-arresting experiences, where light and digital art responds to physical space and the people who populate it. Yet, behind and beyond the ethereal qualities of Squidsoup’s work lies the technological and logistical realities that makes an installation of over 40,000 individual lights amongst a crowd of 10,000 people (as was the case for Four Tet’s Alexandra Palace shows) possible. Formed in 1997 by the artist and designer, Anthony Rowe, Squidsoup defines itself as an ‘open group of collaborators’ working across (digital) art, design, technology and research. Alongside Anthony and the group’s six core members, there is a team of full-time and part-time staff, freelancers, as well as a warehouse, workshop, studio space, and fabrication facilities. With Squidsoup’s trajectory corresponding more-or-less alongside the major digital advancements of the past 20 years, the group has been continually successful in bringing technological innovations into the realm of art, performance and the material world.

As Anthony explains to NR over email, without the level of digital connectivity we experience today (such as 5G, the Internet of Things and “ever smaller processor sizes”), much of Squidsoup’s work would not be possible. Being able to adapt and change alongside the progression of technology and the digital realm is only one part of Squidsoup’s story, however. As Anthony notes, “interesting ideas are normally [those] pushing the boundaries of what is reasonably possible – either in terms of materials, software, engineering or logistics. Originality and novelty are highly-prized attributes in this kind of work; to achieve that, you need to be pushing the boundaries.” Now, as Covid-19 alters the ways in which we experience and use digital and physical space – perhaps, in some ways, irreversibly – Squidsoup are learning to adapt again. In response to the pandemic, the group have unveiled Songs of Collective Isolation, a piece which reconceptualises the larger, immersive installations that Squidsoup are known for on a more intimate, or individual, scale. “This is not a piece for massive social interaction,” Anthony outlines – rather, it’s a “contrast, a parallel track to our larger public artworks.” And as much as it is evidence of Squidsoup’s ability to respond and react to the world that their work is shaped by, it’s not the end of those bigger works: “Perhaps it is also in part a memento to those larger projects, and a sign of hope that those days will soon return.”

How did the idea for Songs of Collective Isolation come to fruition, and how will this piece work in real-life settings?

Songs for Collective Isolation emerged from a series of explorations, looking at the possibilities of minimal, slow-paced sound- and light-scapes, free from the need to think about practicalities such as people flow, visitor experience and dwell time. We wanted to create a piece that would slowly draw you in, using natural and unadorned sounds, and exploring the effects of layering multiple iterations of the same sound, each from its own speaker suspended in space. The result is a raw set of sampled sounds (a violin recorded very close up, played by Giles Francis) that gains depth and breadth when played independently through multiple speakers – it fills out; becoming an orchestra, rich and deep, from such simple beginnings. We also saw a parallel with the current global situation – social distancing, lockdowns and so on. The potential of what we can achieve together, and the fragility of isolation that we were suddenly confronted with, seem to resonate within the piece. The piece starts with a solo note that, only after quite a while, begins to build in strength and variety.

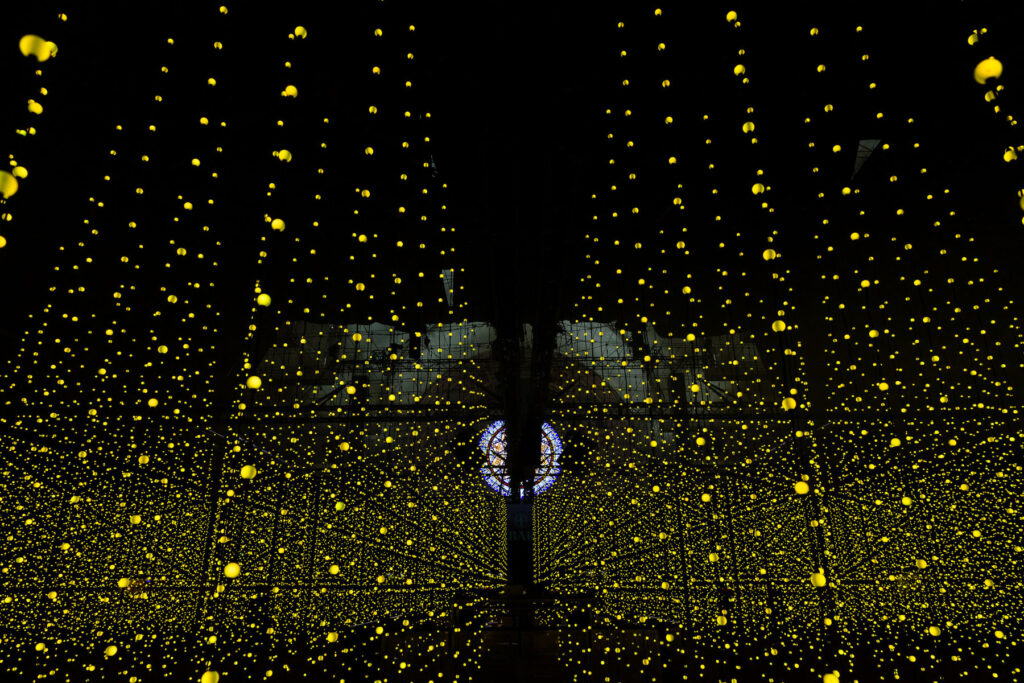

The work uses a hardware and software system we have been developing in-house for the past few years, that we call ‘AudioWave’. It is the same system that was used at Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art in Arizona to create a piece called Murmuration (2019-20) that comprised over 700 individual speakers and orbs of light, suggesting the movement of light and energy around the outside of that building. It builds on earlier iterations such as Wave at Salisbury Cathedral, Desert Wave at Burning Man and Canal Convergence, and Bloom, first commissioned for Royal Botanical Gardens Kew. This piece is much smaller, more intimate, with just 18 light/speaker orbs. It is designed to be seen in quiet, private or controlled spaces – again resonating with the current situation.

The footage of Where There is Light is poignant to watch; How was the work, with light responding to the stories of refugees and asylum seekers, developed?

From the outset our goal was to create an abstract space in which people could listen to some real stories from real people; refugees within their midst in Gloucester. It was also important, I think, that this was done in a positive way, as part of a non-lecturing experience. And finally, we wanted to bring attention to the amazing work of GARAS (Gloucester Action for Refugees and Asylum Seekers). An opportunity arose to show the work in Gloucester Cathedral, and we worked with Everyman Theatre and Music Works, two local organisations, to put the piece together.

Visually, we wanted each of the four testimonies to have a different feel, a different visual reference. And finally, there is a musical crescendo where we took the opportunity to let rip with the lights a little! The project was a collaboration with a refugee organisation local to the studio in Gloucestershire UK called GARAS. We all hear stories of refugees, but the enormity of their ordeals is so outside of our experience, that attempts to represent their lives becomes mired in the discussion of guilt, responsibility, economics and race.

How did Squidsoup’s work with Four Tet come about?

Having created indoor and outdoor versions of a project called Submergence and shown it numerous times in various types of spaces and events, we felt that the approach of the work, using a walkthrough 3D array of points of light (controlled in real time) to create the impression of movement and presence in a shared physical space, could be adapted for use elsewhere, in particular in live stage performance. In 2015, Kieran Hebden of Four Tet was finishing the album Morning/Evening, that was, for him, something of a stylistic departure consisting of two long, meandering, Indian-inflected tracks, and was wondering about a live set. A mutual friend connected us.

“The plan from the start was to search out serendipities; happy coincidences where two working processes coincide, creating – hopefully – more than the sum of their parts.”

The first shows (Manchester International Festival, Sydney Opera House, Roundhouse) had a conventional stage layout, with our volume of lights behind Kieran on stage. For a gig at the ICA in London in 2016, Kieran suggested placing himself in the centre of the room, on a low riser, in the middle of the lights. The audience, also within the installation, surrounded him, effectively breaking down the wall between audience and performer – placing them in the same space and creating a different kind of audience experience. A hybrid of performance and installation; a blurring of boundaries between stage and audience space; plus, of course, the mixing of physical and digital inherent to the original idea of the work. The ICA had an audience of 300, as did National Sawdust and Hollywood Forever, US, which we then expanded to some 6-to-700 at the Village Underground (Shoreditch, London, 2018), and eventually the 9,000 plus at Alexandra Palace. Upcoming events in Berlin and the USA are currently on hold due to the COVID situation.

Has the collaboration with Four Tet changed the possibilities of experiencing live music?

New possibilities for experiencing live music are emerging in many ways, as technology improves and becomes more available. None of what we do would be possible without a myriad of technical innovations. We have been pushing the relationship between performer and audience, performance and immersive installation experience as described above, aiming to deliver new types of experience. But we are not alone in doing this. The collaboration with Four Tet is an example of a creative partnership looking for new ways to engage audiences and expand performance – to create novel kinds of experiences. In one key sense, this has been a rare opportunity. The relationship Four Tet has with his audience is unique: they are cerebral, with high expectations, but they do seem up for new things. Not every audience can be trusted to treat the work with the physical respect it needs: the LED strands dangle in among the audience – a different audience could easily pull and break them.

What informs the ways that Squidsoup responds to different environments?

Most of our larger commissions are awarded, so we respond creatively to a specific space or cultural brief, and we also use these commission as an opportunity to advance our own agendas and work. In effect, this means that we use the space, location, community/audience, and any brief we are presented with as a canvas, and the systems and technical approaches we have developed are the paint (or medium) to create a new piece. Enlightenment, a project we installed in the North Porch of Salisbury Cathedral, was informed and inspired by the symbolic importance of the cathedral, its history and presence, and was also a response to the nature of the space. At a practical level, we needed to take into account people flow into the building, and to consider how the light and sound bounced off walls, and so on; the affordances of the location. The Polaris work at Burning Man was almost the opposite in terms of approach and experience. The first time we did it, we had no idea what we were getting into; we just liked the idea of an LED cube driving around the desert. We were invited out by Cyberia, one of the camps at Burning Man, to give it a go using an ex-army truck. What could possibly go wrong?

“It was a baptism by fire, and the answer is pretty much everything went wrong (generators failing, dust getting literally everywhere), but we learnt what needed to be done for kit to survive out there.”

We were lucky to be invited to return the following year, where we both re-ran the Polaris project and were also commissioned to create a new work for Burning Man 2019: Desert Wave.

It’s fascinating to see Squidsoup’s progression from the early works to some of the large-scale bespoke commissions. Is there a direct connection between these earlier pieces with the present day?

Definitely. Our work has always been about immersion – working to create beguiling trance-like experiences and making the tech an invisible enabler, rather than a prominent component. Visually, our works have moved away from using screens, as the screen is a boundary; a barrier between the viewer and what they are looking at. We wanted to break down that barrier, either by placing the viewer inside the content, as with VR, or by letting the media spread into our shared, physical world. For us, VR felt too lonely an experience, where you leave this world behind, so we looked for more hybrid approaches, eventually landing on the various approaches using arrays of lights (and sound) in physical, walkthrough, shared spaces.

As our work has developed, it has become more abstract. This is partly due to the nature of the media we now use, but it also feels right for us, as it allows for quite a primal, visceral form of engagement. It also allows each person experiencing the work to decide what it means for them. That, in itself, is an interactive and creative process. What is consistent throughout our work is a will to remove the technology from one’s conscious experience. We’re not pretending it’s not there (our work is quite technologically ambitious), but we don’t want people feeling that they are engaging directly with ‘computers’. This is partly because they are a means to an end, not a focus in themselves in our work, but we have noticed that people change their approach when confronted with digital/binary decisions. They start to think about how it all works, which is absolutely not what we are looking for.

“We want people to suspend disbelief, to go with it and experience the work with all their senses, rather than their intellect.”

What can people learn from Squidsoup’s interdisciplinary approach to combining technology and research with music and art?

Interdisciplinarity is increasingly necessary in our work, but I’m not sure that we actually see it that way. We see it more as collaboration between people with different skills, as we need a range of skills and expertise in order to make real our artistic visions. Learning advanced computer, materials, robotics, music, design and architectural skills, and so on, takes time and, if you’re not working with a trained professional, there will be a lot of learning by trial and error. Even when you are using a trained professional, we often end up asking them to do things that are out of their comfort zone anyway – so trial and error, and iteration, are the order of the day. Connected with this is communication. We often work remotely, even more so these days, by necessity due to current movement and social distancing restrictions, so getting an idea across clearly but accurately is vital when working with people from various disciplines. Although our projects generally start with a fairly clear concept and idea, there needs to be a degree of pragmatism involved during the development phase. Some aspects of an idea may be impossible, or better approaches may be uncovered along the way. Being able to see these and work around or with them when they arise, is crucial – and also down to communication. The flip side to that is that it can also be tempting to dilute an idea for the sake of practical expediency. Any changes of direction are carefully thought through to ensure that the core concept is not compromised.

Squidsoup is described as something that can ‘be experienced online […] and in shared spaces’; how do you anticipate the different ways in which participants might engage with the work, either in real life or via online footage?

In mid-2020, the variety of ways that people can engage with our work are significantly compromised by social distancing, travel restrictions and other knock-ons from the current pandemic. Our best-known works are experiential physical spaces, in galleries or outdoors at festivals and other events. But we do also create permanent exhibitions, and smaller artworks that straddle the area between installation and art object. Currently this is a main focus; to make smaller works that can be experienced in private and smaller, more controlled, public spaces. Although our works have been shown many times, the world is a large place and the most effective way to speak to global audiences is through the web and social media. We have not made a web-based artwork for many years, but we try to document our work in an honest and truthful way, so that people who can’t actually make it to an installation can still get some understanding of what the works entail. However, most of the online content associated with our work is generated by visitors. Social media users have been kind – many of our projects are very selfie-friendly. There is a definite irony there, as one of our stated aims (as mentioned above) was to move away from screen-based experiences to physical ones. And yet here we are, with many more people knowing our work from digital content than from encounters with the physical work.

Designers

- Submergence, 2019, Canary Wharf image by Rikard Österlund

- Four Tet, 2019, Alexandra Palace image by Rikard Österlund

- Four Tet, 2019, Alexandra Palace image by Rikard Österlund

- Four Tet, 2019, Alexandra Palace image by Rikard Österlund

- Desert Wave, 2019, Burning Man image by Travis Cossel / Black Label Films