Tom Hancocks

The illusionist shaping the space of tomorrow

What does designing space mean when the human perception of its living environments is experiencing an unprecedented moment of transition? The profound change we are witnessing, unlike in the past, is no longer simply aesthetic, but gnoseological and psychological too.

As the walls between factual and simulated reality are collapsing, such a reflection no longer seems to gravitate around stylistic issues but calls for a rethinking of the role of the interior designer themselves, as well as of their platforms of expression.

Since speculation about the Metaverse and its impact in shaping our future lives began, many brands — some more hysterically than others — chased the trend, coming up with their own virtual spaces. Their needs were met by a generation of creatives that, by making the most of AI and design softwares, unleashed their imagination. Social media became their springboard and many brands, from fashion to music, their patrons.

Just like the radical designers of the Seventies kept most of their utopian projects on paper but still reclaimed their revolutionary stance, this new frontier of design could perhaps represent a futuristic shift for the whole industry albeit proudly reclaiming its digital-only existence. Are now the self-trained rookies of the internet taking over the professionals thanks to the freedom and viral visibility offered by social media? How far can we go with dismissing self-designed digital footwear or chair concepts as fakes when they could, in return, inspire a change in the industry? Perhaps it’s time to surrender to the illusion.

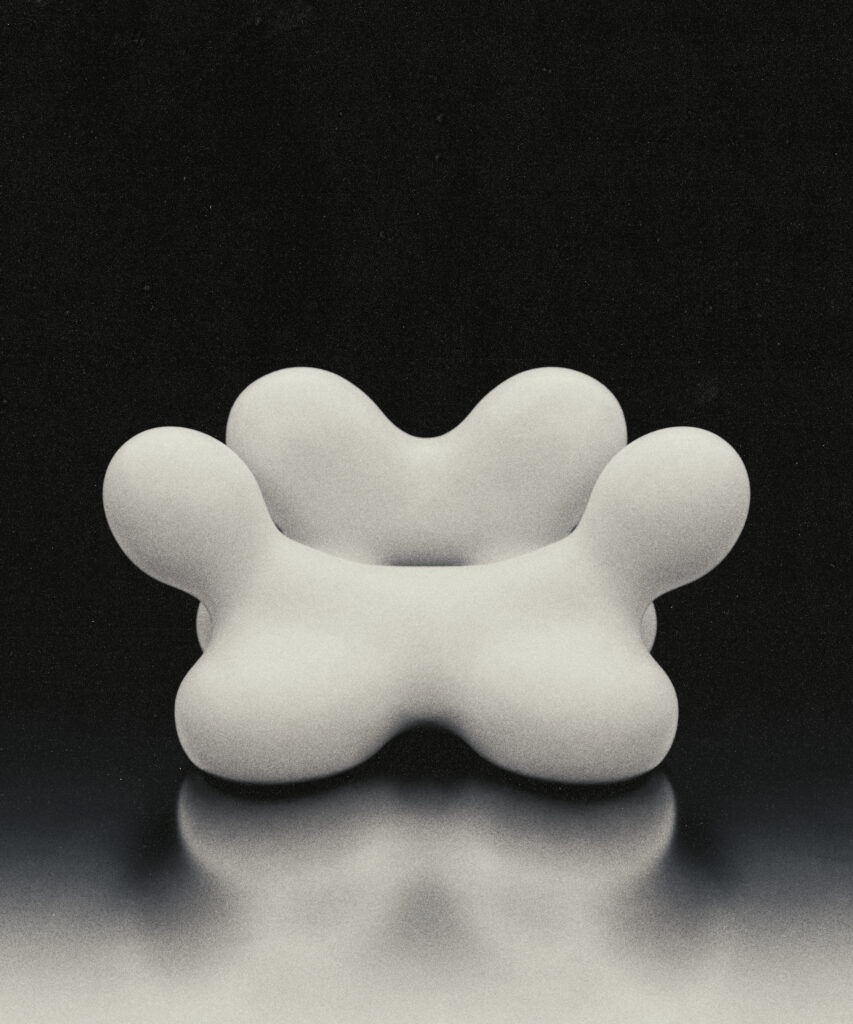

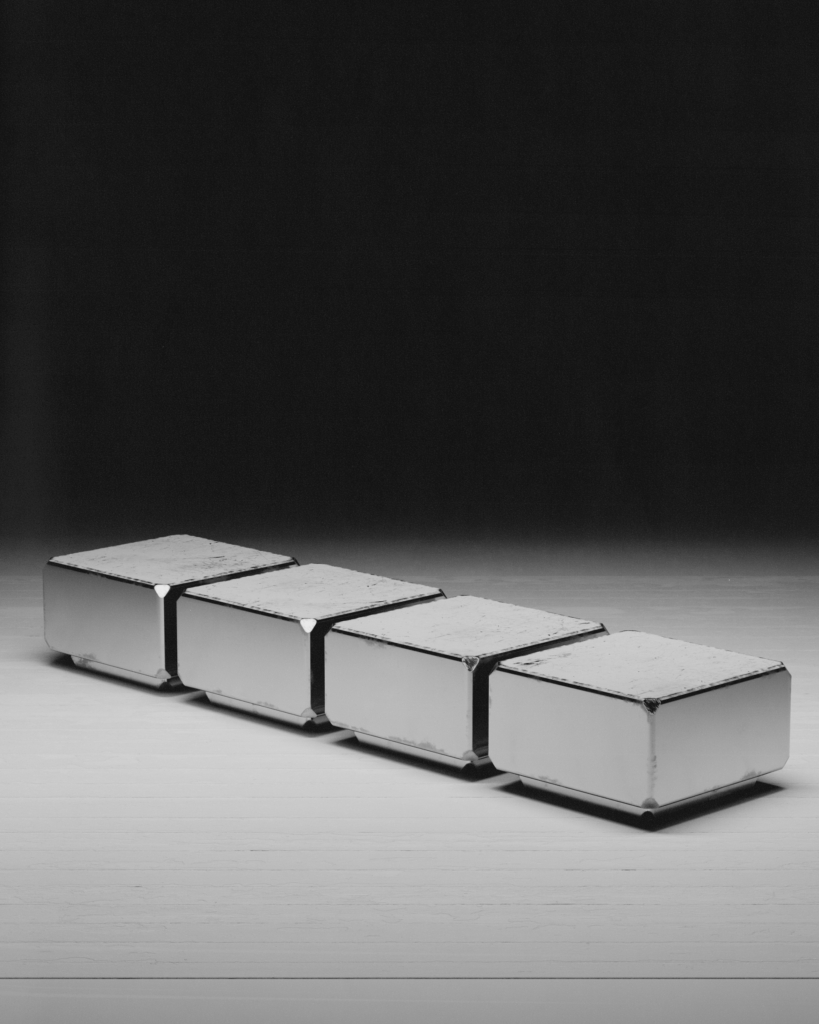

To dive deeper into the exciting opportunities and the controversies of this still fully unexplored realm, we spoke with Tom Hancocks, the Australian designer whose uber-realistic furniture and interiors may equally just be some of the most eye-pleasing you’ll see online — and some of the most adventurous, design-wise.

This issue revolves around the theme of Virtuosity, which is something that may resonate with you more than many other artists since you’re self-taught. This may sound as something equally liberating and scary. Did the absence of any academic learning process freed your virtuosity and somehow unlocked new creative trajectories?

I believe so. I also feel that ‘self-taught’ is a term I’ve regretted using as I’ve grown older. The absence of an academic influence is certainly something that has dictated my trajectory. I think it helped by allowing me to have more agency over what influences and communities I could organically gravitate towards, but on the other hand, you also miss some of those unanticipated experiences and exposures that can be stimulating to react to. So, whether one is better than the other, or if that had an impact on virtuosity in particular is hard to say.

How did you come to the decision of avoiding formal teaching in the field of design?

I would say mainly because of the accessibility of the internet. Because of how drawn I was to that growing up, formal teaching in any capacity never seemed like a necessity, especially in something as fluid as art or design. Sure, the resources of an institution would have been great, but it’s a luxury that is intentionally withheld from a lot of people, so I went in a different direction.

Although created digitally, your projects do retain an extraordinarily strong and fascinating dimension. This leads us to ask you what, in your opinion, virtuosity means today?

I would instinctively say that virtuosity is the ability to communicate something, very effectively, through creative expression. So, I would argue that the intent only matters if the art is meant for others, or to convey something to the world. But it’s something that’s entirely up to the viewer to decide in somewhat of a self-determining way.

What that means today in particular, though, is hard to say, as there’s more stimulation and communication than ever. So, maybe, ‘virtuous’ is what is most pure and able to cut through all that noise.

The great Gio Ponti was among the first to argue that design, art and architecture were made to interact among themselves. Having worked with fashion brands, design firms and even music artists, do you make interdisciplinarity a core of your practice and a necessity for the contemporary industry?

Absolutely. I think art and design is nothing if not just a form of communication. And as most would tell you, expanding your perspectives and experiences will almost always lead to more reward, if that’s something you’re able to do. That’s also a big part of digital art, though. You have this very malleable tool to reimagine just about anything. So that helps a whole lot as well, of course.

How do multiple and diverse stimuli inform your work?

My process is fairly inconsistent because I usually try to wait for the right ideas to come to me. But this same approach can lead to running into creative walls too, and feeling like everything isn’t a purely original concept, which means it’s somehow dishonest.

“I try not to get too fixated on one style, but rather navigating around and carrying my taste and values into different genres.”

So, although I think that everything is some kind of subconscious reimagination, I would like to get better at doing more direct sampling and using that to further explore ideas that feel more unique. I actually think about this a lot in parallel to music sampling, and how beautiful it is when done in the right way.

Your Instagram bio reads ‘digital sketchbook’, which suggests that the content displayed isn’t necessarily devoted to pragmatic scopes. Does working in the digital field grant you a creative and experimental freedom that you wouldn’t otherwise experience?

Definitely. Art and the creative flowing of ideas can sometimes be hindered by pragmatics. It’s nicer to look back at things I’ve posted and see a progression of ideas or themes, rather than a perfectly refined portfolio.

The sketchbook idea is because, in the arena of social media and its fleetingness, I’d much rather just gesture to an idea. That’s the extent of the communication I want to make there. If something will only be seen for 5-10 seconds, then I don’t need to get too much across, just a sketch.

How speculative can design be in an increasingly digital society?

Extremely. A big part of digital art is just visualisation of ideas and concepts. If people are able to see something visually, it will inevitably create a stronger reaction. Which then hopefully provokes a more engaged response.

Up to just a few years ago the idea of designing furniture and objects exclusively for digital fruition would have sounded heretical. Do you feel like you’re contributing to rewriting the perception and rules of your industry, perhaps helping other designers to better understand, even in real life, the bond between objects and the space they occupy?

If I do, it’s really not something that I’ve thought about much. But not because I think I’m above it. More because I don’t think I’ve fully integrated into an existing community or an industry, since I usually don’t resonate with what’s at the centre of them. So, I feel more like I’m navigating around the outskirts just following my nose. But if that in itself can inspire others to do the same, then I would be very excited to see what that leads to.

Thinking about the school of Radical Design, some of the most brave and adventurous projects conceived in design and architecture were born as utopian and never truly brought to life. Others — like much of the Gufram catalogue, for example — were put into production thanks to brands that believed in the intuition of young, revolutionary creatives that refused the traditional norms of the industry.

Do you believe that the prominence of digital platforms and experimental and out-of-the-ordinary designs can give firms the push to be braver and, as a consequence, foster a new exciting season in design — from furniture to fashion?

In all honesty, I’m not sure. I do agree that digital, creative-based platforms allow for more of those things to be seen. But as capitalism grows exponentially and everything becomes more commodified and monopolised — including digital spaces and assets — those forces will always work against the progress of creativity and culture. So I agree with the former, but I don’t see firms becoming braver any time soon, nor young creative people having more time or resources. Same goes with digital spaces becoming more democratised. I think the opposite is happening, unfortunately.

In the past, design goods also represented an elitist status symbol and they were often connected to physical possession. Is the rise in popularity of NFTs as well as digital designers — from sneaker and football shirt concepts to furniture or uber-realistic AI-generated content — somehow replacing physical desirability with a virtual and more democratic one?

Most definitely. From virtuosity to virtues. So much postmodern theory has already touched on this, so it’s probably better to reference that rather than hear my bastardisation of it. But I will say there seems to always be an inevitable contradiction between the designer and the consumer, until one or the other won’t exist any more.

One puts them-self into the world, and the other takes the world for them-self. Which is not to justify some artistic prejudice. I don’t think those roles are inherent, and anyone can create something beautiful, but until we abolish those roles and change the relationship we have with art and design, these exploitations will always occur.

Credits

Design · Courtesy of Tom Hancocks