For Freedoms

By definition, a super PAC is a political action committee that is able to raise an unlimited amount of money to influence the outcome of political elections in the United States. Yet, For Freedoms, a super PAC registered back in January 2016, is somewhat unconventional in its intentions and approach. As the first artist-led super PAC, For Freedoms was created by Eric Gottesman and Hank Willis Thomas to encourage greater political engagement through art – and to engage people in complex conversations that have become simplified into binary concepts.

For Freedoms has made an impression on both the world of politics and art since it was registered. In 2016, the super PAC opened their ‘headquarters’ at the Jack Shainman Gallery for a takeover exhibition there – and have since been hosted by MoMA PS1 for an artist residency in 2017 to coincide with the first 100 days of the Trump administration. Their exhibition at the Jack Shainman Gallery provoked a national discussion about police brutality after Dread Scott hung a flag at the exhibition headquarters, whilst their ‘Make America Great Again’ billboard in Pearl, Mississippi caused controversy for its depiction of Trump’s election catchphrase imposed on an image from the Bloody Sunday march of 1965.

Through their use of advertising as a super PAC, their background as artists, and their commitment to creating change, this project by Gottesman and Willis Thomas hopes to open up necessary political and cultural conversations. Speaking over the phone, Eric Gottesman talks through the motives of For Freedoms, the role of advertising, art and propaganda, and why we should come together, regardless of political agenda.

NR: Where did the idea of forming a super PAC originate?

Eric Gottesman: Over the course of several years, my friend Hank [Willis Thomas] and I, had these conversations about art and politics. Both of us are artists, we both address politics through our work in various ways – I should say, other people talk about the politics of our work. But both of us are interested in the overlap of art and society, and so over the course of those conversations, we often talked about doing something that directly engaged with systems of politics. We talked about maybe having an artist run for office, but eventually, decided to start the super PAC in the fall of 2015, after talking to a number of lawyers about how to do go about it – so we did really before the 2016 election started in earnest.

NR: Something I was actually going to ask is whether the political climate in the run up to the election was a factor in forming the super PAC.

EG: No, not really – it came before that. It was less about any specific candidate or campaign, than it was about the way political discourse happens in the United States.

“The oversimplification of complicated situations and political solutions often leads to the factionalization, and people retreat to notions of nationalism that are extremely simple but not necessarily the best.”

So we wanted to see if we could expand the political discourse to encourage or allow people to talk with more nuance about complex issues.

NR: Do you think that the culture of politics today reflects advertising, because of this simplification?

EG: Very much so. This was something we were very interested in, as a super PAC is basically a political advertising agency. We decided to take on the most egregious part of the problem – which is that money filters through organisations and into our politics, in order to create extremely simplified forms of advertising that is supposed to shape how to think and how to vote. We wanted to shift that up and play with that idea.

NR: By buying advertising space for billboards, newspaper, and online, can your political advertising be interpreted as a form of propaganda?

EG: I think it can be, it usually is. Advertising has got much more complex and savvy – often times, you’re being advertised to without knowing it. It doesn’t just take the form of propaganda; it now also takes on the form of ‘culture’ in certain ways. But I also think there’s a pedagogical difference between propaganda and art.

“Propaganda works behind an argument, whilst art offers dialogue. Propaganda has a certain kind of insistence that advertising also has, as opposed to art’s openness.”

NR: How can For Freedoms stimulate critical engagement when political discourse is reduced to this culture of advertising?

EG: That’s exactly what we’re trying to figure out! So far, this has involved trying to merge artistic and political discourse, bringing political content and conversations into art spaces, using our access to these spaces as artists – and vice versa: we’re trying to find ways to bring content out into the public, that we produce as artists. So, we’re bringing politics into art and art into politics through various means. We are also holding a series of town hall meetings and conversations, often in conjunction with exhibitions that we curate. And then, for next year, we’ve got our 50 state initiative, where we’re going to have a presence in all 50 states in the lead up to the 2018 election.

NR: The idea of town hall-style meetings, feels as if it is taking communication back to a pre-internet era, back to before everyone interacted online, to having that physical meeting with your community. In that sense, are you trying to bring people back together?

EG: That’s an interesting point, I hadn’t really thought about it like that. One of the things we thought a lot about was to try to ‘make dialogue great again’. I don’t think we’re doing it out of nostalgia, but we are trying to inject a form of humanism into the modes of dialogue that we use now. I think the way in which we communicate on social media is fantastic, as we are much more connected in a certain way – but the trade off is that it demands that we use short hand to encapsulate messages and conversations we want to have. There’s nothing wrong with that form necessarily, but I do think that we need to be able to have deeper, broader conversations about things that go beyond 140 characters.

NR: And there is the danger of communicating with only those who share what you want to see.

EG: That too – and we see that a lot right now, which is one of the things we’re really trying to work on. The art world also has that echo chamber effect, so we’re trying to figure out how to access all parts of society. How do we reach a wide range of people that might be interested in helping us build a movement around building a better political conversation, even if we don’t share the same political agenda?

NR: What is the incentive for people to come together in public spaces despite opposing views, in the interest of shaping the future?

EG: We already do this: we’re consuming the same culture, and as a result of that culture, we form our (political) identities. I think there’s this notion that, only certain people will be interested in art, and only certain people will come to a museum and participate in something like what we’re doing. The assumption is that cultural production only lends itself to one set of opinions – that you agree/disagree, you’re a democrat/a republican, etc. A lot of these binary concepts are much more complicated, so when you ask why somebody with a different set of ideals would want to have that dialogue, I think it would be because we want to better understand, and hopefully to encourage an atmosphere that allows people to appreciate those different views.

NR: Whilst we’re consuming the same culture, places like art institutions can be off-putting to people who feel alienated from them. If there is a way to make these places appeal to a broader range of people, can that instigate better dialogue and a sense of community between different groups of people?

EG: Absolutely. I’m one of those people that feels very alienated by art, and I do think For Freedoms is as much a rebuke of the art culture and the art world, as it is to the world of politics. Art institutions are already political: they make decisions about who they include and exclude. In order to address that, we need to insert conversations about who’s included, and who’s excluded. These are essentially political questions that are at the centre of our political structure. If we insert these questions into the museum, hopefully we can shift what is defined as art, and what is not – and change who is defined as the art viewer.

NR: Do you think the problems with the financing of super PACs in a political context, are issues that also need to be addressed within the art world?

EG: As an artist, I look at the art world as being this enormous archive of capital that determines what has social value in our culture and so, there are two ways to respond to that. The first, which is how I have responded for much of my career, is to think: “fuck that! I don’t care about that, and I don’t care about those rich people! I’m just gonna do my thing and work in my way, and hopefully at some point after I die somebody will recognise my brilliance and that will change the world.” That’s one way, and the other way would be what we’ve done with For Freedoms, which is pretty new to me to be honest. The way we have done it with our super PAC is to confront the art world, and to claim a space by participating in this world of extreme wealth that governs and shapes how art is valued. For me, the real issue is figuring out how to shift the system so that wealth doesn’t necessarily determine culture, and so that artists are recognised for their power, and are able to utilise the power they possess. Art is used in every society, whether it’s through propaganda or commercial wealth, and so what we’re trying to push for is for our society to value the role that artists play in shaping, not just culture, but how our society works.

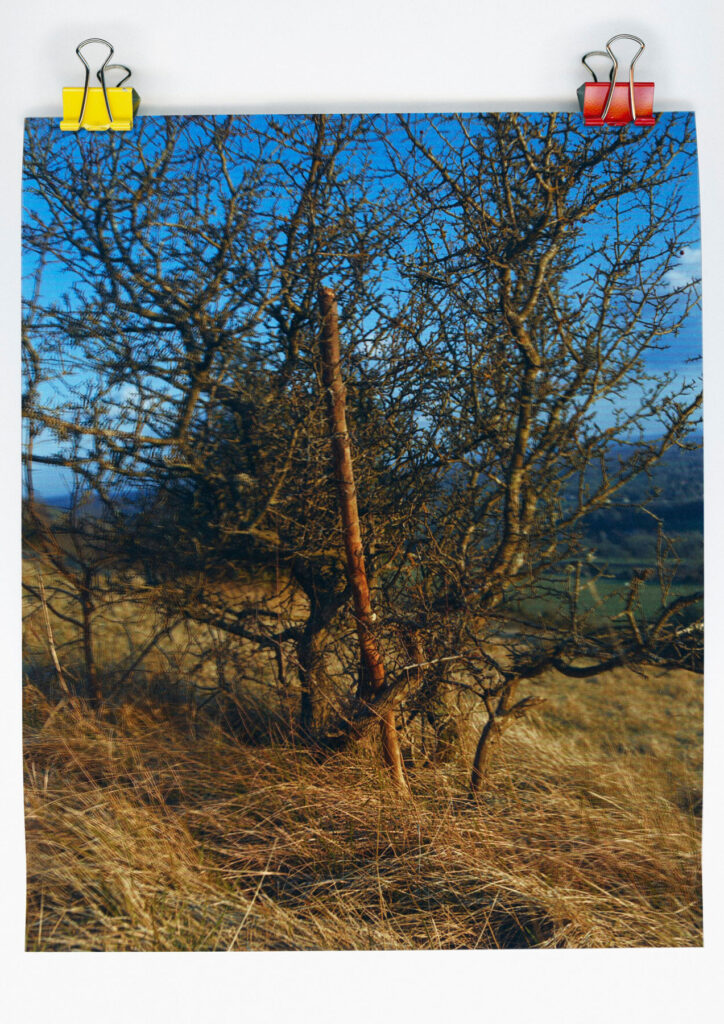

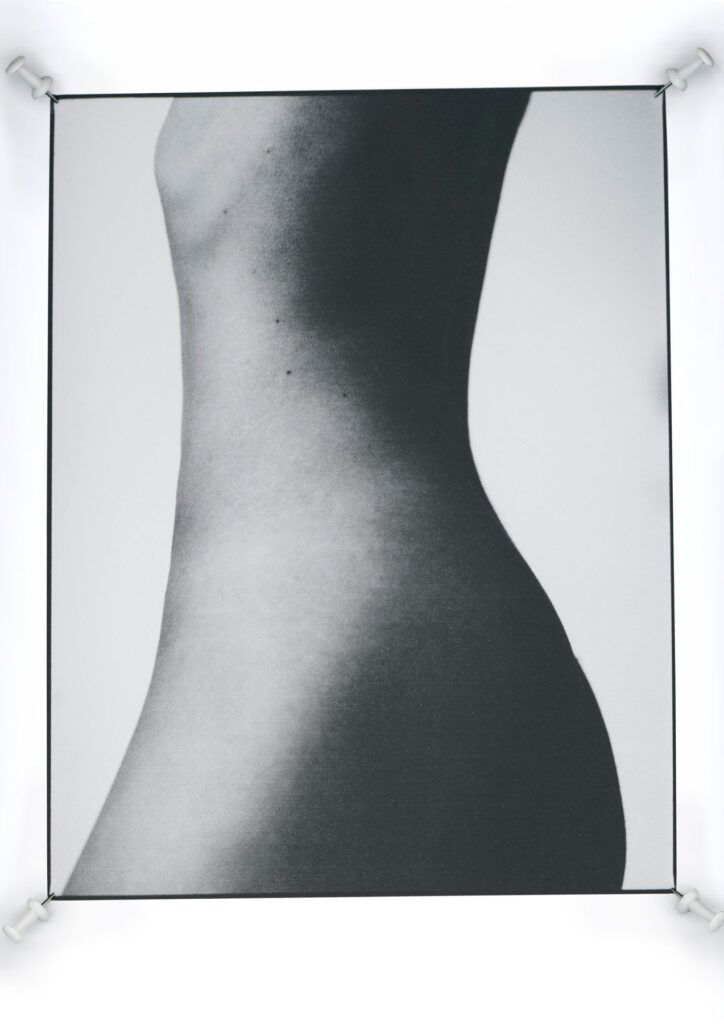

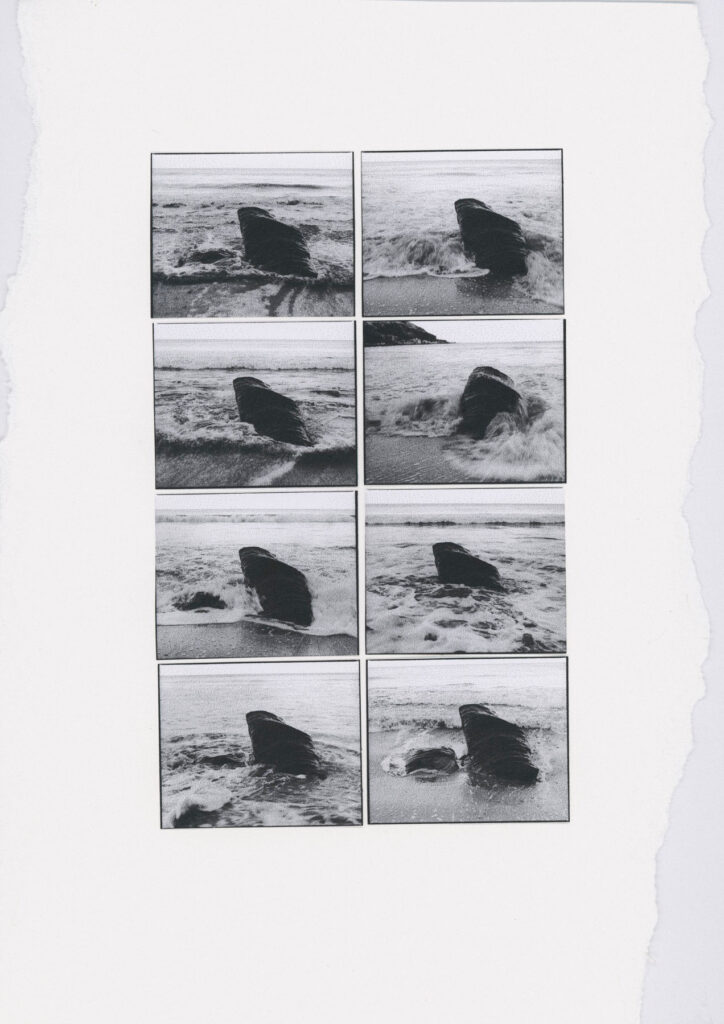

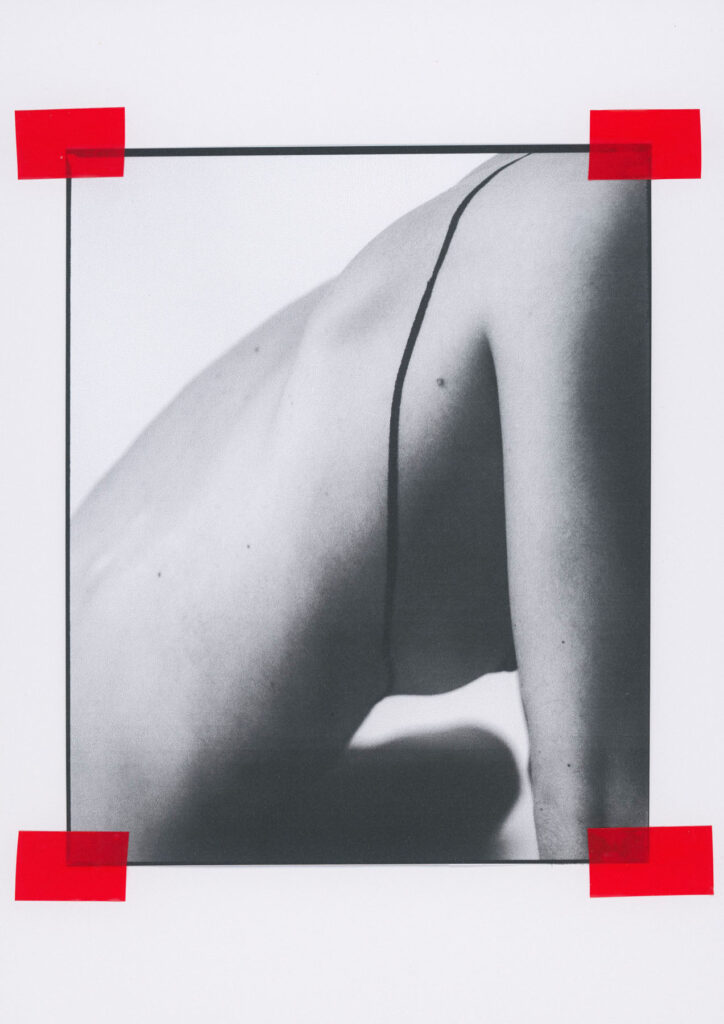

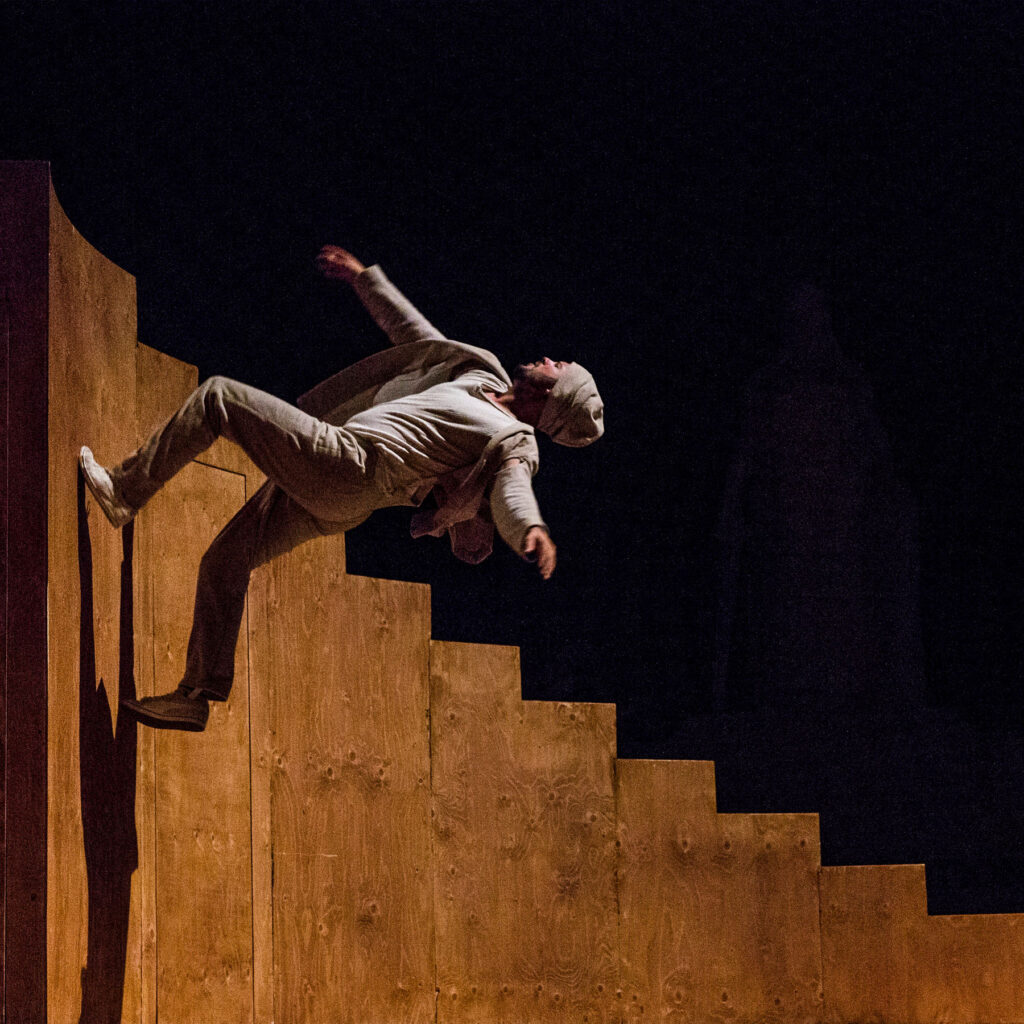

Photos

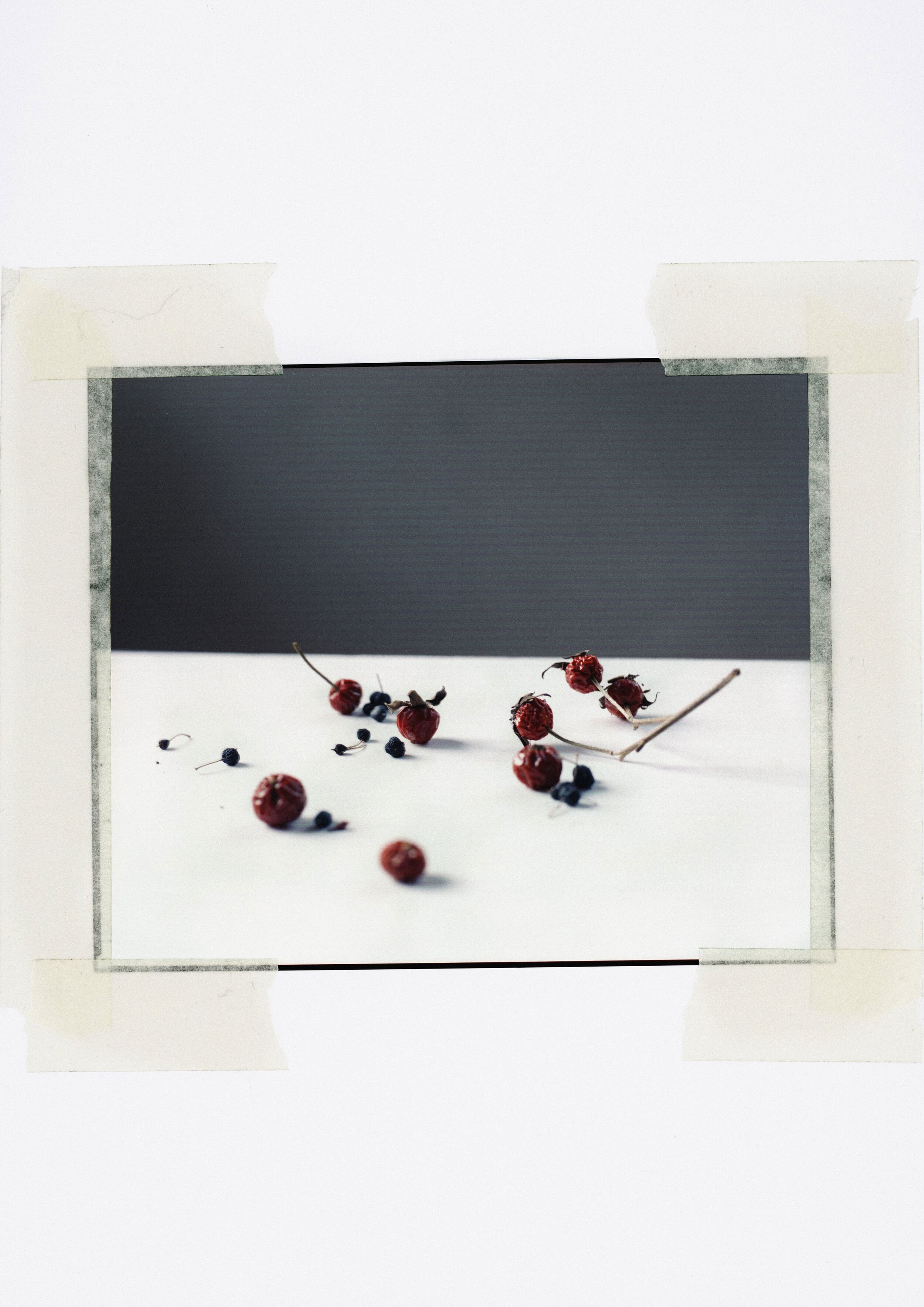

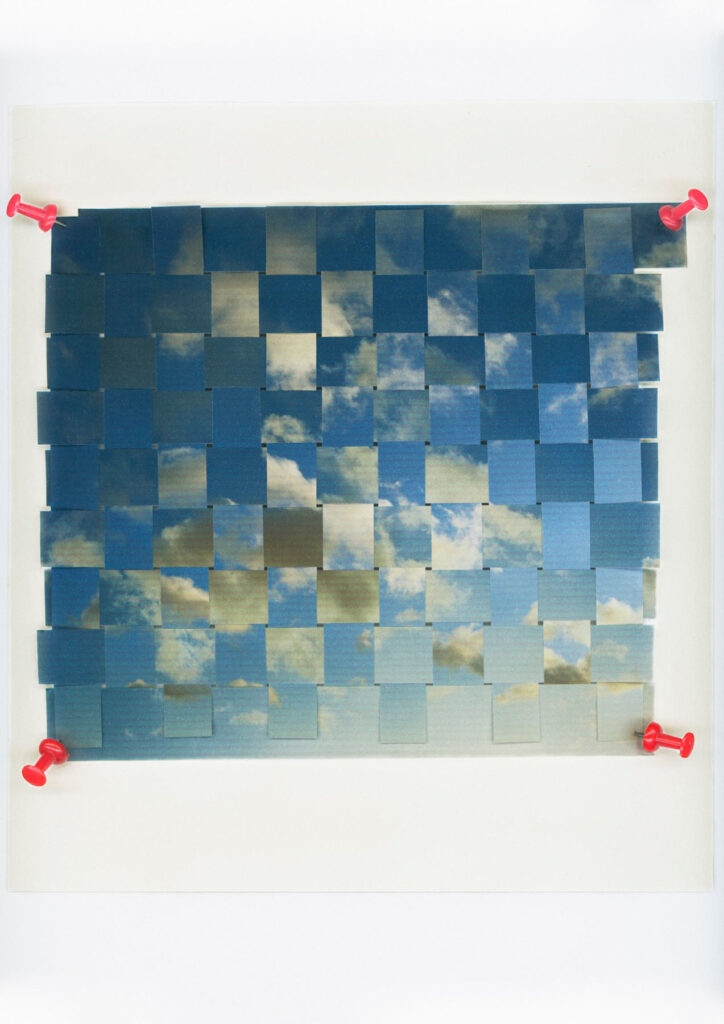

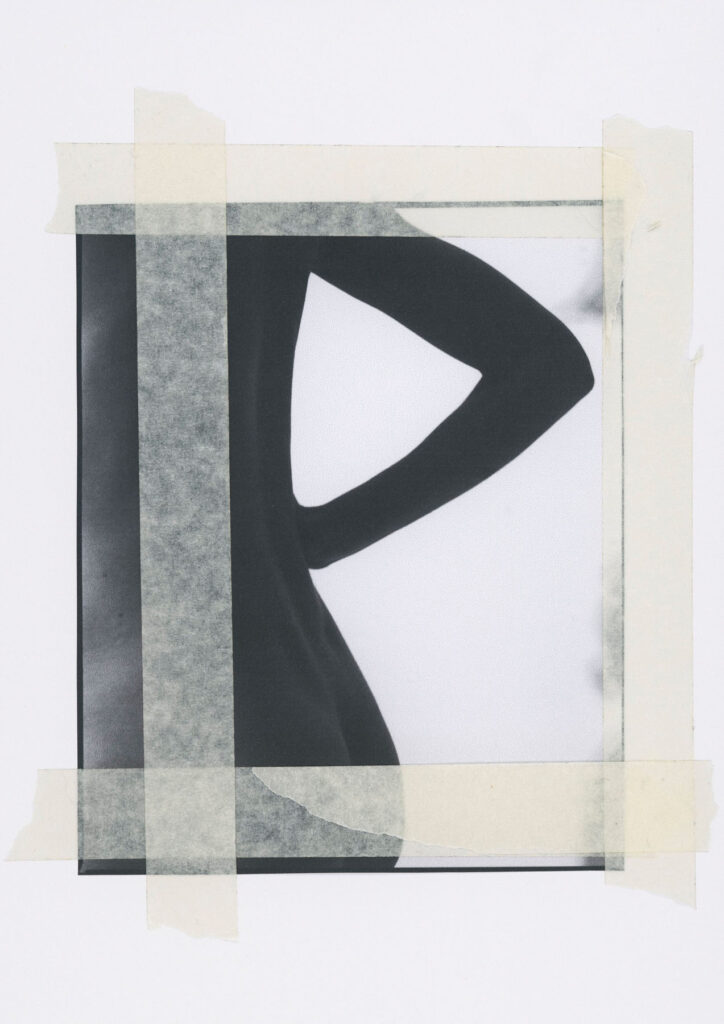

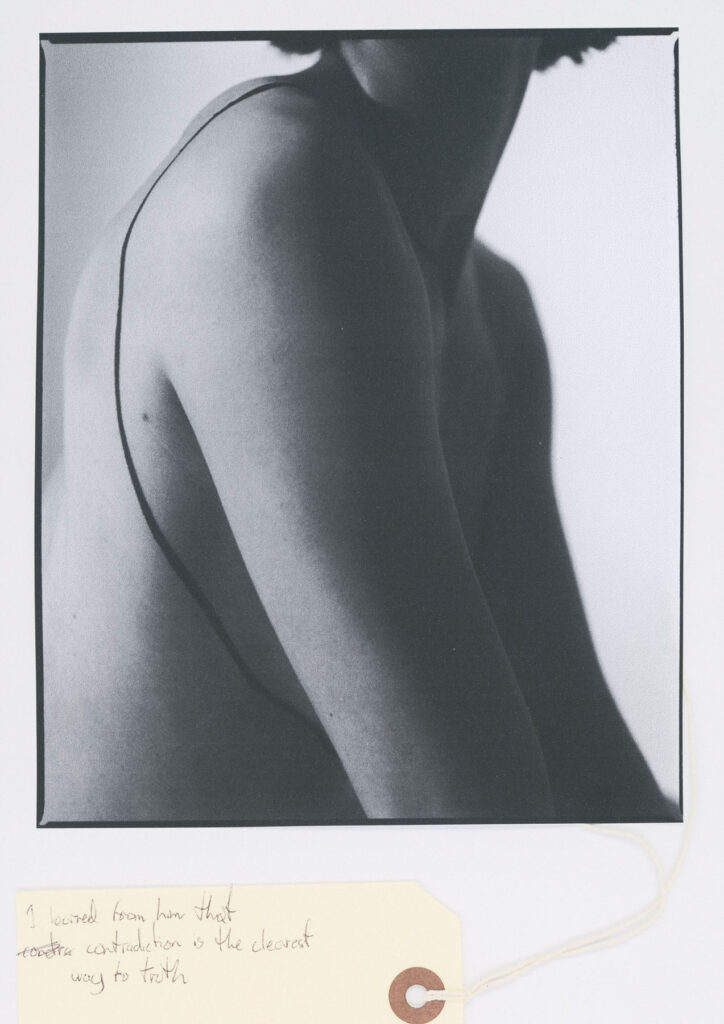

- Mass Actionwith Nari Ward – Lexington, Kentucky

- Not Voting Is Actually Voting with Eric Gottesman – Flint, Michigan

- A Man Was Lynched By Police Yesterday with Dread Scott

- With Democracy In The Balance There Is Only One Choice with Carrie Mae Weems – Cleveland, Ohio