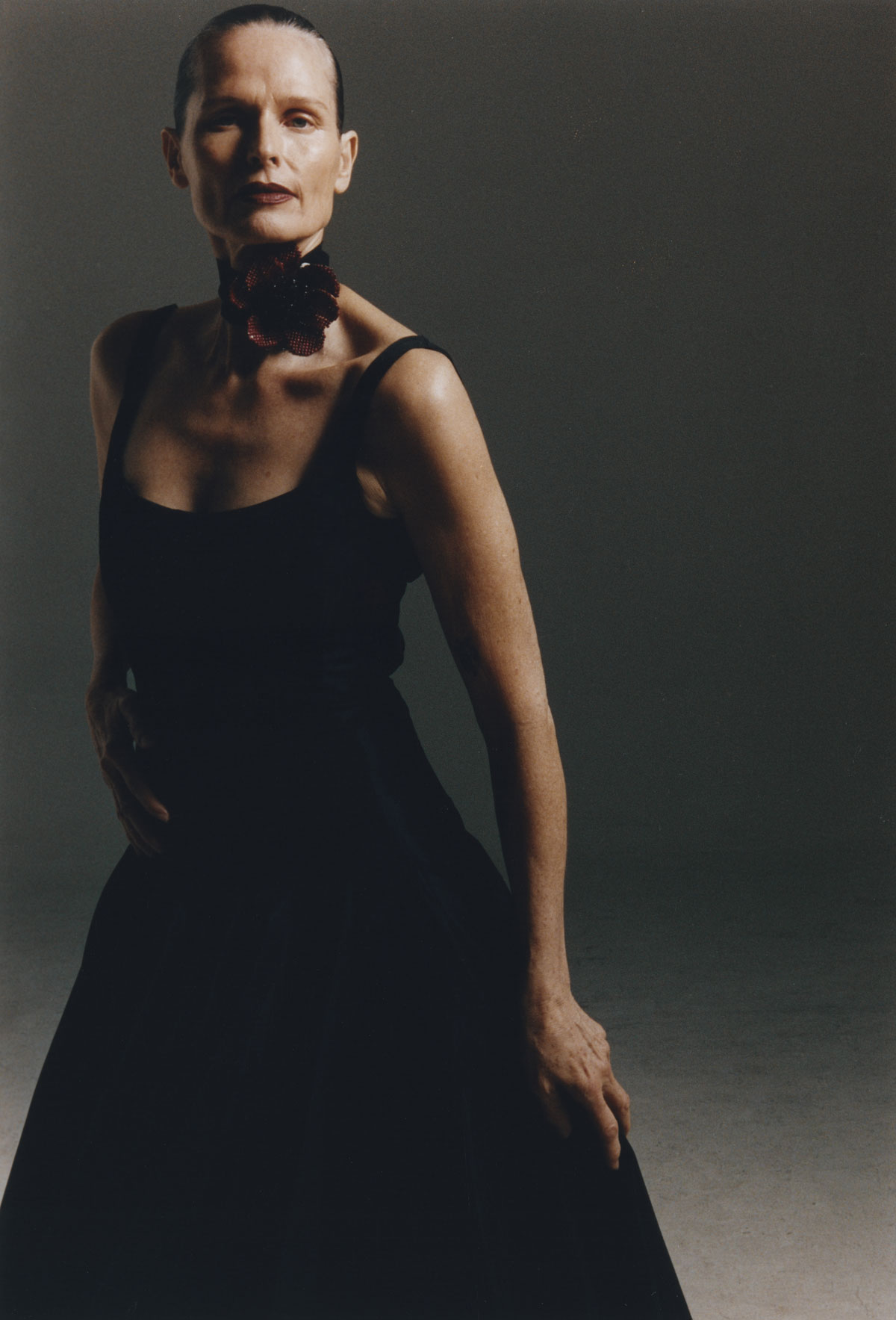

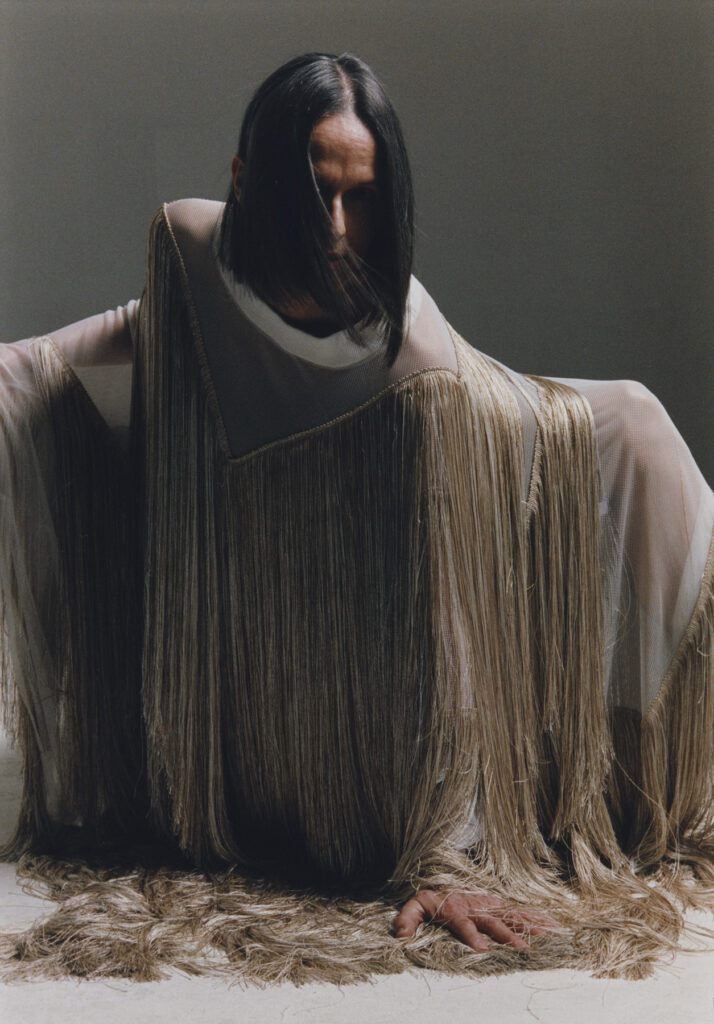

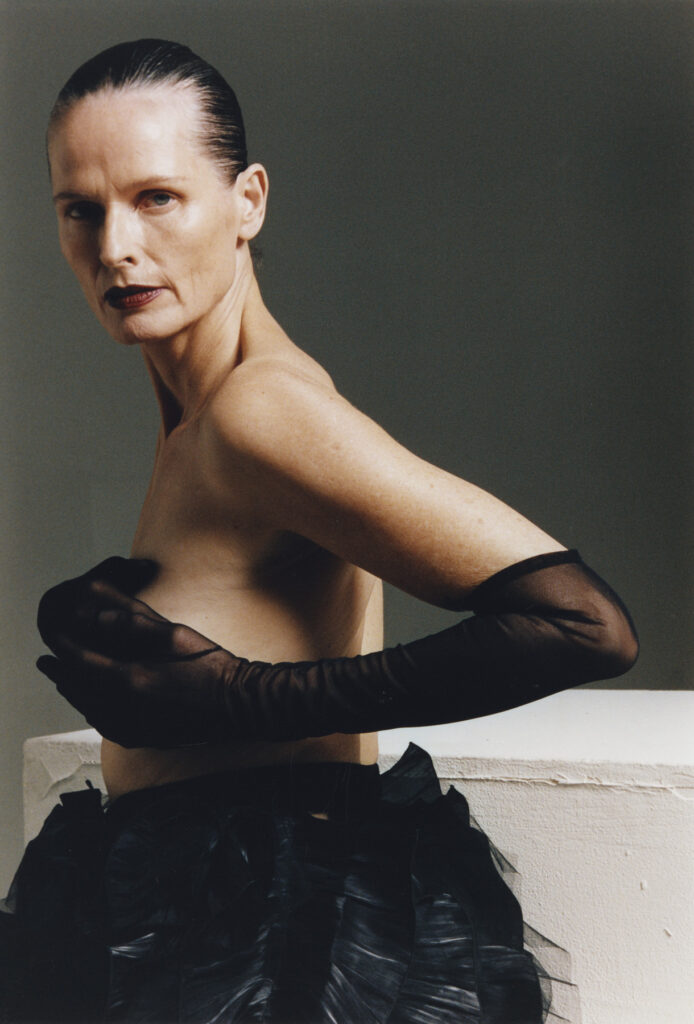

Experimenting with boundaries until the intangible becomes tangible

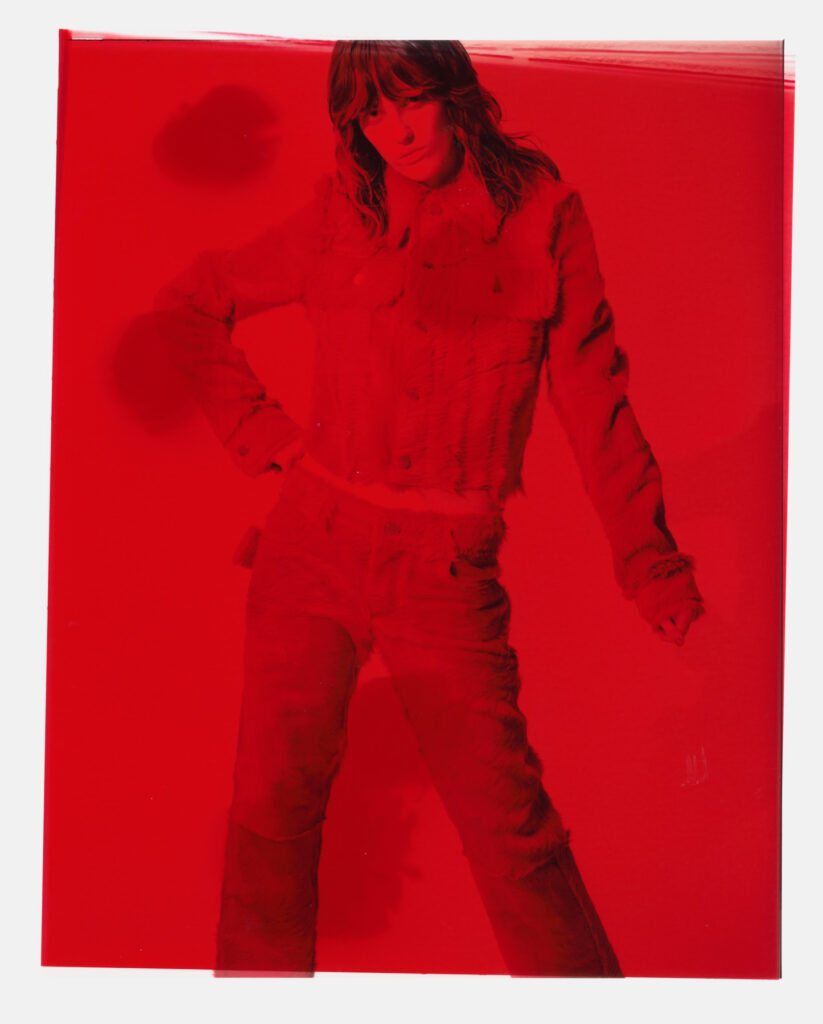

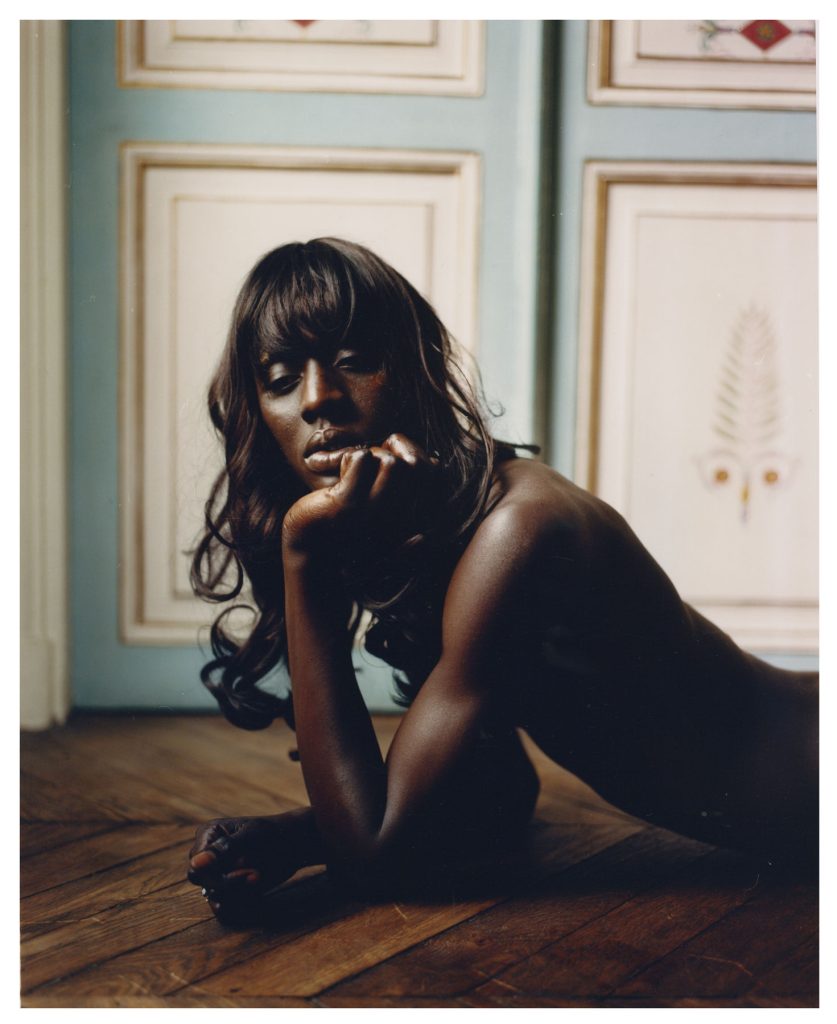

Testing the limits of the boundaries communities and self impose shapes the utopia Andrés Reisinger aspires to manifest. His visual artistry intersects art, design, music, architecture, fashion, and beyond, always moving along the waves of culture and never settling for anything marked as conventional. The results give birth to the manifestation of a hybrid reality, one where the intangible becomes tangible. The duality of the physical and digital realms, the fruition and transition from a blueprint to reality, the faces of strangeness and their unearthly appeal, and the celebration of a newborn: everything moves in and out of Reisinger’s creative ethos.

NR: The first thing that caught my attention was your title on Instagram: Unclassifiable Artist. Does this indicate the millions of ideas you want to test and of creative endeavors you want to venture to?

AR: I would agree with that. I have been inspired by the Argentine writer Borges, who was also Unclassifiable. I am focused on constant self-improvement, constant experimentation, constant development; wherever it takes me.

My task is to keep discovering and introducing new mediums of work and ways of experiencing art and design. So, my practice cannot be easily classified, because it is not something that I can fully classify yet, and I probably never will.

As an artist, how essential is it to be multidisciplinary? Do you think a creative should focus on a single discipline in art?

My work is based on pushing the boundaries between the digital and the physical realms to achieve hybridity. In this sense, I consider and love visual culture as a whole, essential in all of its declinations. There are incredibly interesting intersections that we are seeing and can be further developed between art, design, music, architecture, fashion and so on, and my work is heavily focused on context rather than by piece. Only by mixing different ideas and connecting them will we create new ones.

From Argentina to Barcelona, how do the cultures and communities in these countries – and the others you have been to – influence the way you conceive your works? Can your viewers see the nuances of these cultures in what you create?

Most of the places I have lived in are in South Europe, so my works are heavily influenced by culture from the countries here. These places, for many reasons, have been central social territories, which is something that has influenced my approach to creation and the way I have been sharing my journey on the internet since the very beginning of my career (approximately 15 years ago when I started with digital art and design). I have always felt the need to share the way I see the world.

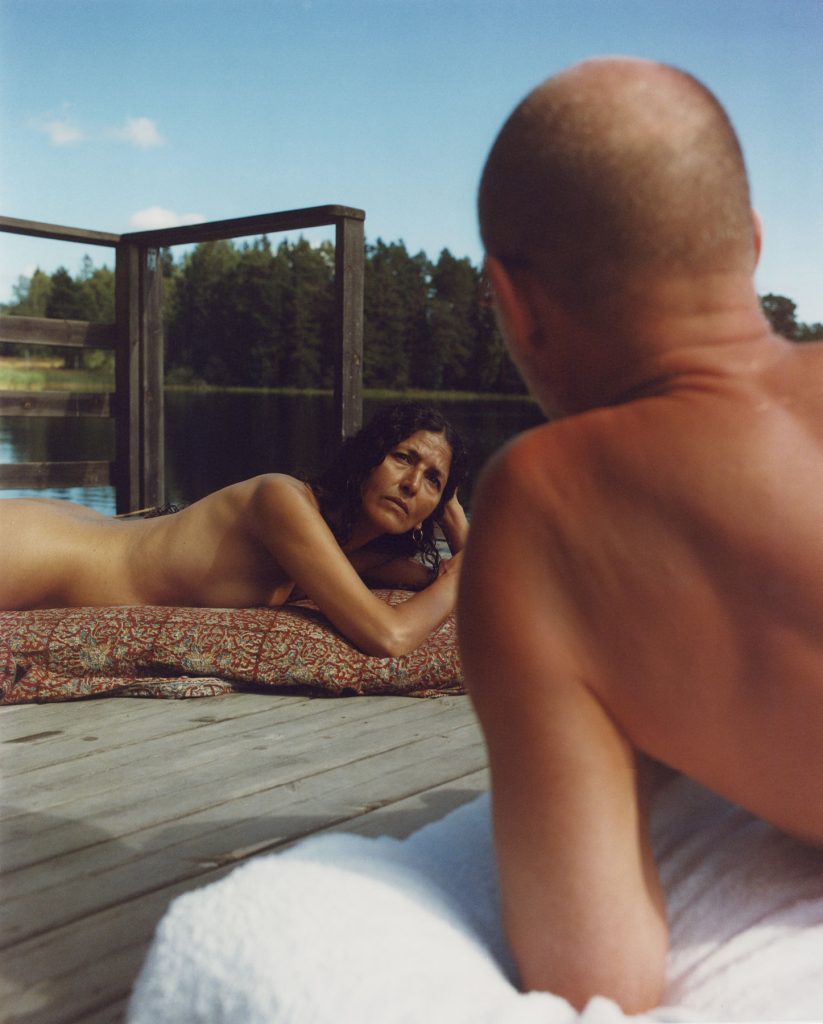

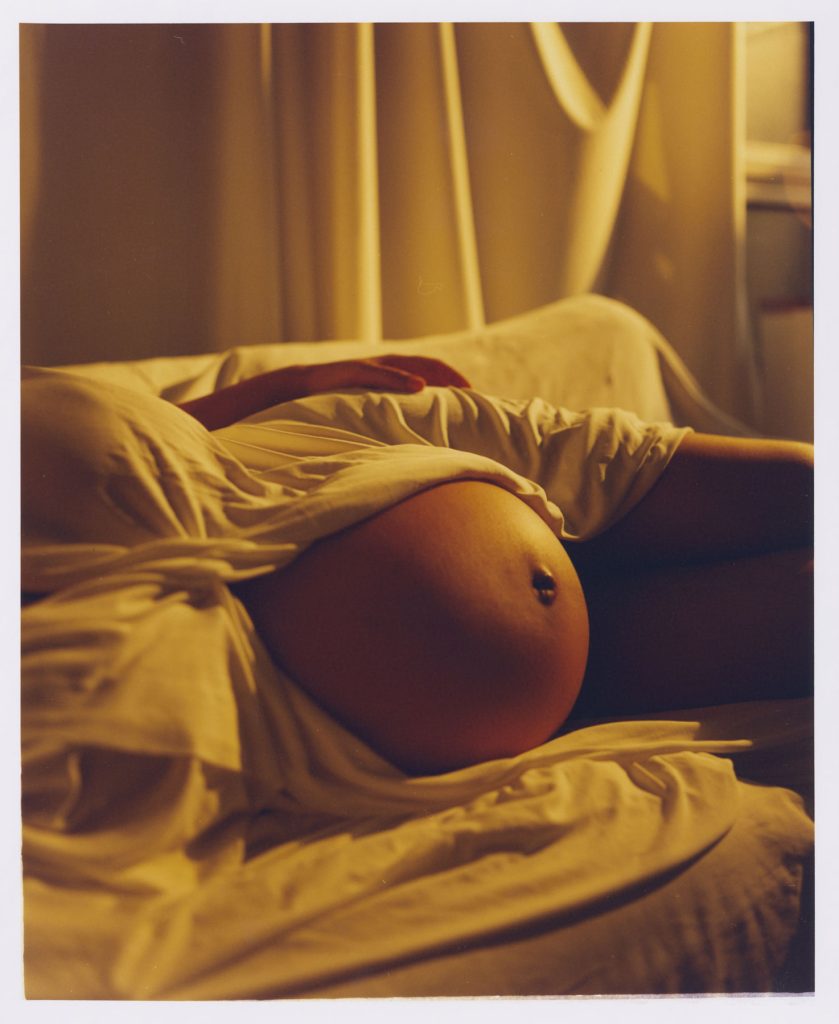

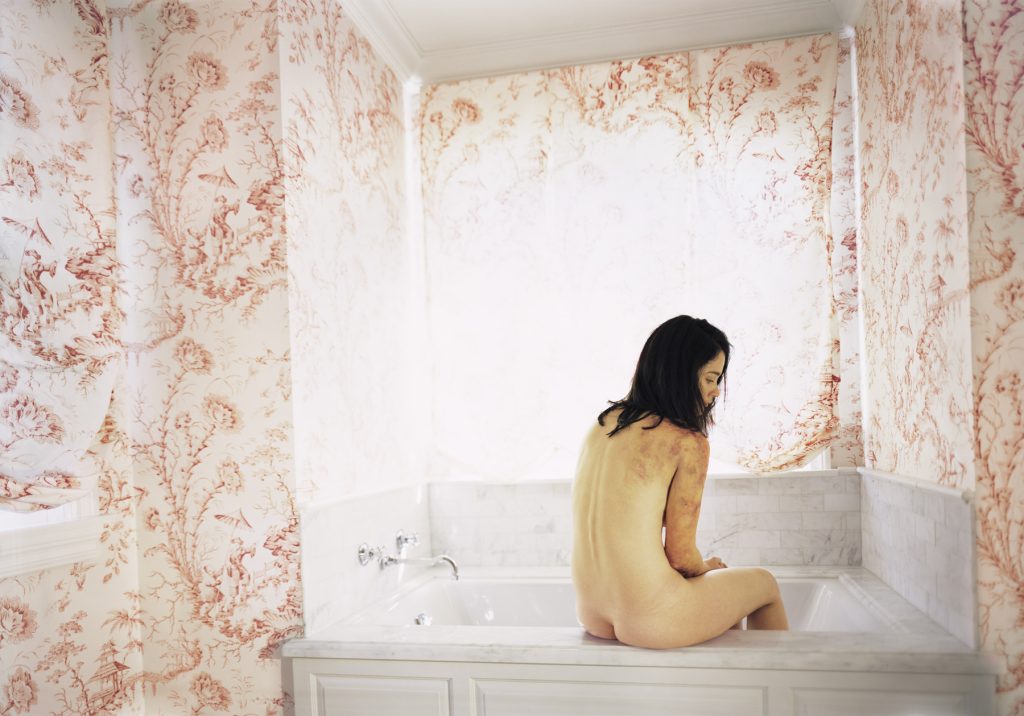

Let us talk about your works. I want to start with An Essay Before Meeting my Daughter. Congratulations, first of all! How do you feel about being a father? How did you celebrate it? Did you feel worried or excited?

I felt all sorts of emotions. It is an experience that cannot be truthfully described or translated. It feels like I am flourishing. It is a novel way of looking at the world. It is an excellent way to cultivate perspective. The way you manage your time, your ideas, and your instincts: they all grow. It is a great challenge in life. It is amazing, and I love it.

Continuing this, you wrote: Anxiety, nervousness, happiness, fears, beloved moments, all that are absorbed and expressed through my artistic lens. Could you guide us on the metaphors of this piece, from the rolling apples to the flipping pages of the books?

The piece was the result of a long reflective process. I wanted to gather and somehow express all the feelings and thoughts that guided these moments of my life, and the piece came very spontaneously as the emotions naturally channeled themselves into form.

With The Shipping, it is the manifestation of a new hybrid reality concerning furniture. How do you envision the future of design in furniture? Would technology replace manual labor?

“I see it as a hybrid of digital and physical; the encounter between the two is already offering an overwhelming amount of possibilities.”

And although it might seem a very futuristic scenario to some, we already spend a third of our days connected to any device screen. We are undoubtedly living in a time where our physical lives are and will continue to be more and more integrated with the digital realm. And as we get more comfortable living in these different spaces, we will get more and more used to owning things and living there.

There are of course differences between the two realities that will never compensate each other. Technology will make things earlier in production, that is for sure, although I cannot say which mode is easier. One thing I can say is that creating a digital chair – such as Hortensia, Tangled, Complicated Sofa, or Crowded Elevator – was the most difficult thing I have ever attempted. Technology can help us do more creative work and less mechanical procedures. Artisans will always exist, and they will benefit from new technologies.

I love the backstory behind The Hortensia Armchair, from having been a concept to a real seat! What made this project challenging? How did you take on the challenge? Did you learn anything from this experience life- and design-wise?

Because it was such a complex design to realize, I was doubting whether to invest time and money to bring the chair to life, so I guess the challenge was against myself. I am incredibly glad that I decided to go for it.

What I am most proud of is that the Hortensia Chair created digital demand before the supply, which is a total disruption within the design industry. We were able to build an interest around a digital object that seemed almost impossible to realize and gave life to it first through a limited edition and then with Moooi in a more affordable version.

It was an interesting phenomenon to witness, with regards to sustainability, most especially. We did not launch another project, hoping for the market to accept it. We created the need first digitally. It showed to design and other companies that this is definitely a possibility.

Continuing the previous question, what do you do when you want to make the impossible possible? Have you ever felt like dropping a project halfway? What made you continue it?

I work with context and try to, in part, deform reality to achieve a surreal atmosphere. That uncanniness between reality and fiction, digital and physical is to make the impossible possible. I do not want my work to be too explicit, or it would defeat its purpose. If it is too blatantly strange, it is instantly dismissed, but if it is not so strange but just enough, it is instantly absorbed into everyday reality. I strive for a slight strangeness leaving the viewers disoriented.

Generally, challenges inspire me, so I have rarely thought about dropping a project halfway.

“If I recognize the possibility of discovering a new production methodology, a pioneering approach within the physical and digital, I will strive to see it through as I know I will learn a lot during the process.”

As we focus on Celebration for this issue, how do you feel about what you have achieved so far in this lifetime?

I am proud, I am humbled, and I am projected into my practice.

Is there anything that we should be celebrating with you in the upcoming weeks?

In mid-January, I presented Winter House, a residential project in the metaverse inspired by the frosty season. It is an important one I would like to celebrate as it represents the preliminary project of an architecture studio for the metaverse I am establishing with other partners. There will be more – a lot more – but 2022 has just started.

Credits

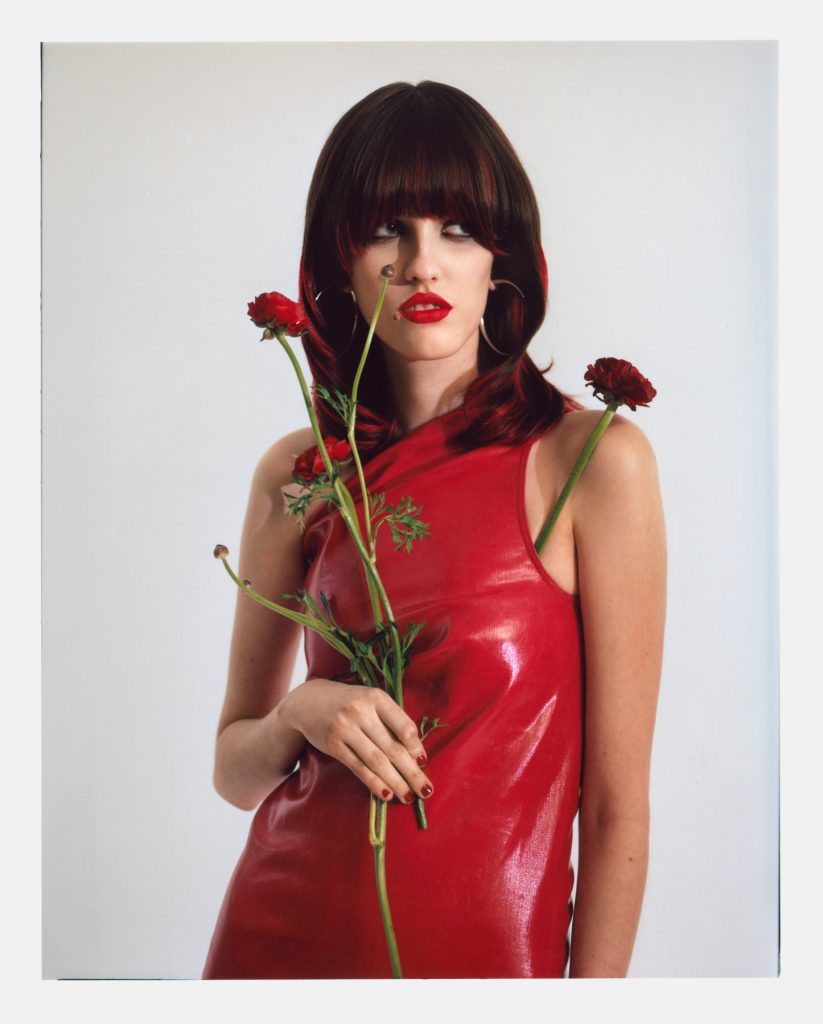

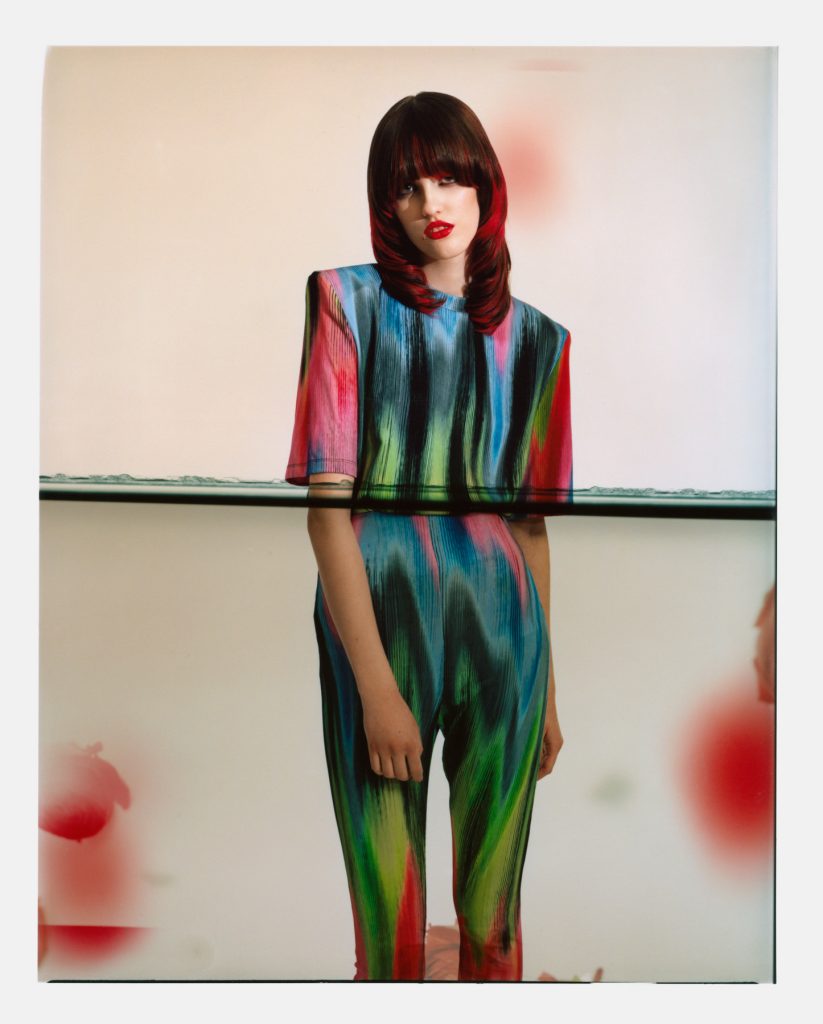

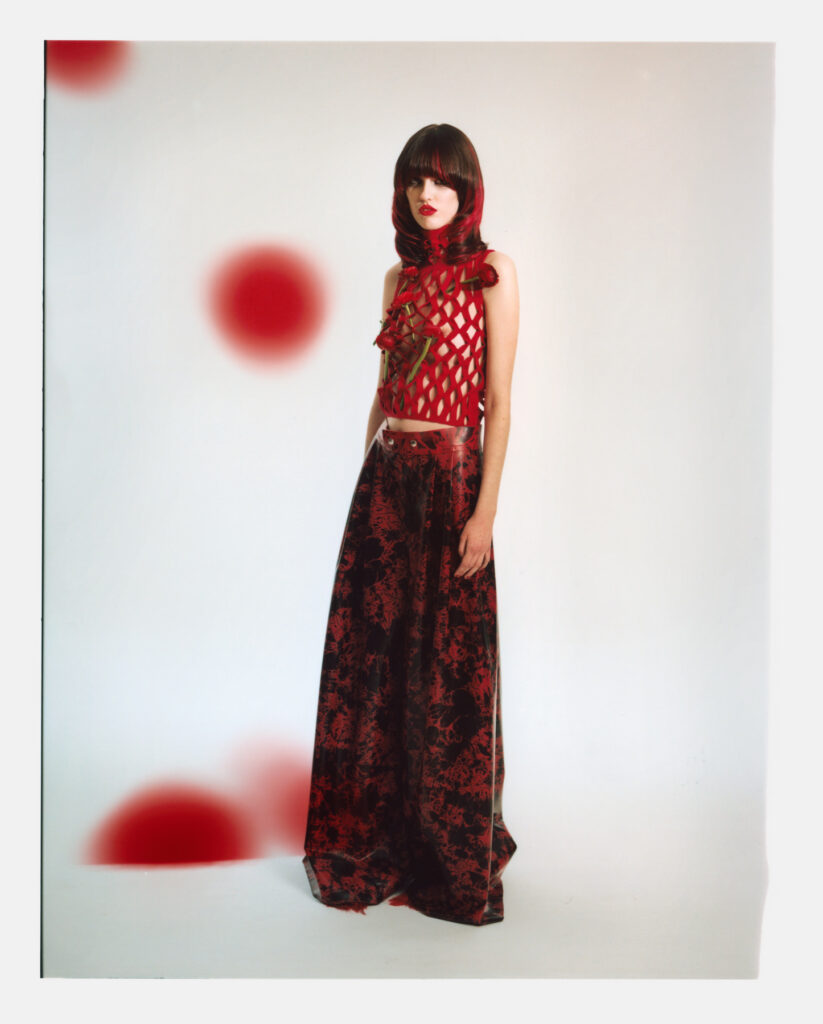

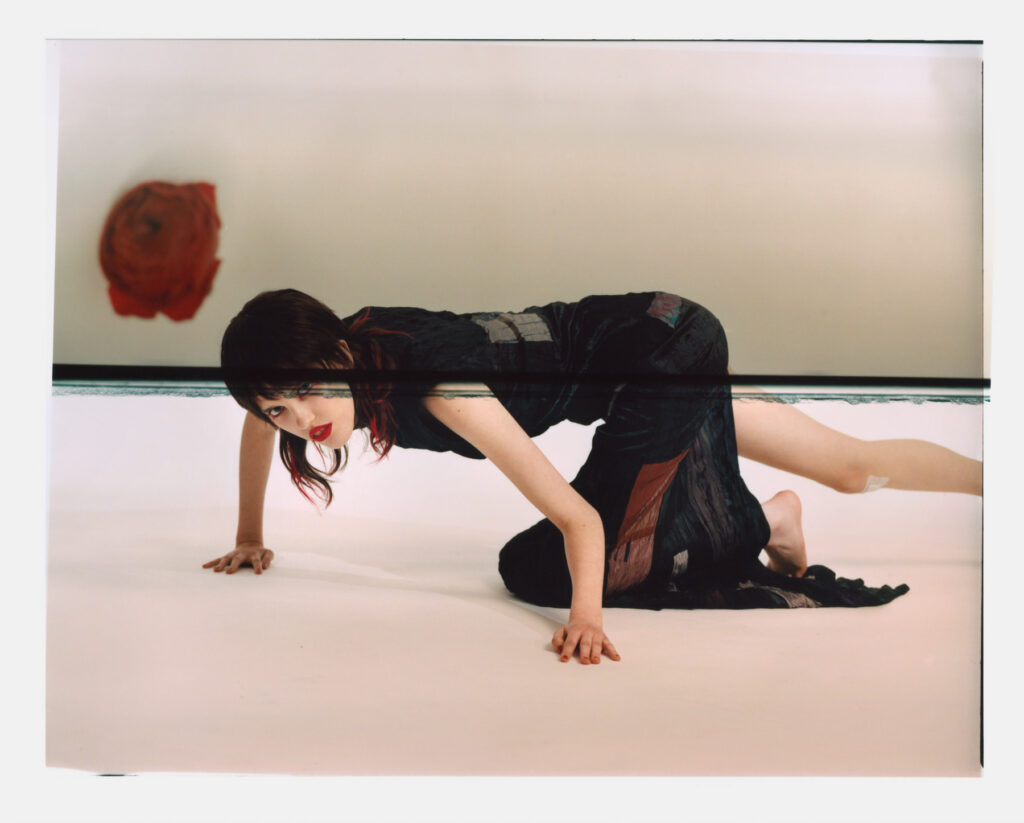

Images · Andrés Reisinger

https://reisinger.studio/