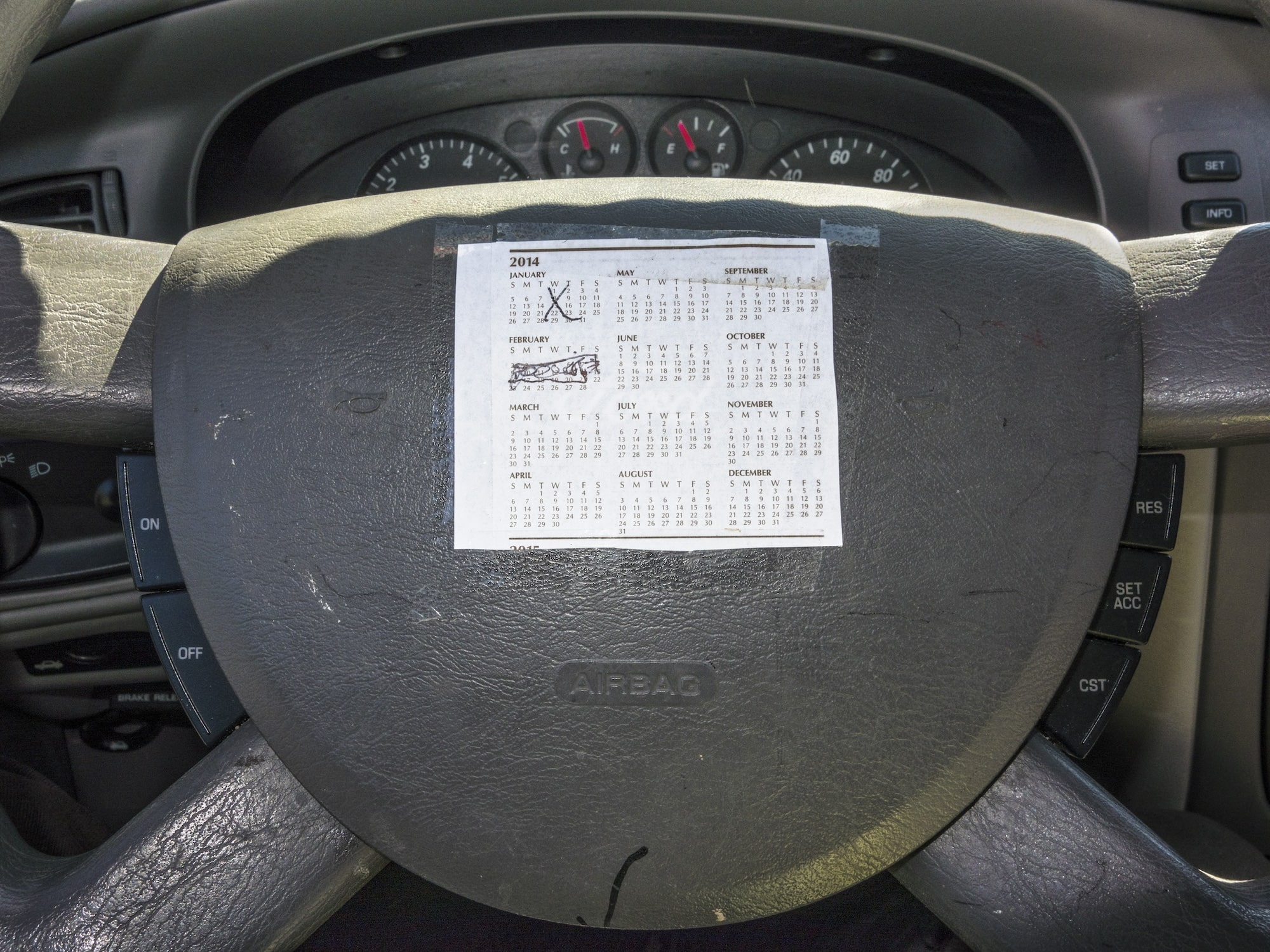

In order of appearance

- Menno Aden, Untitled (Classroom), 2010

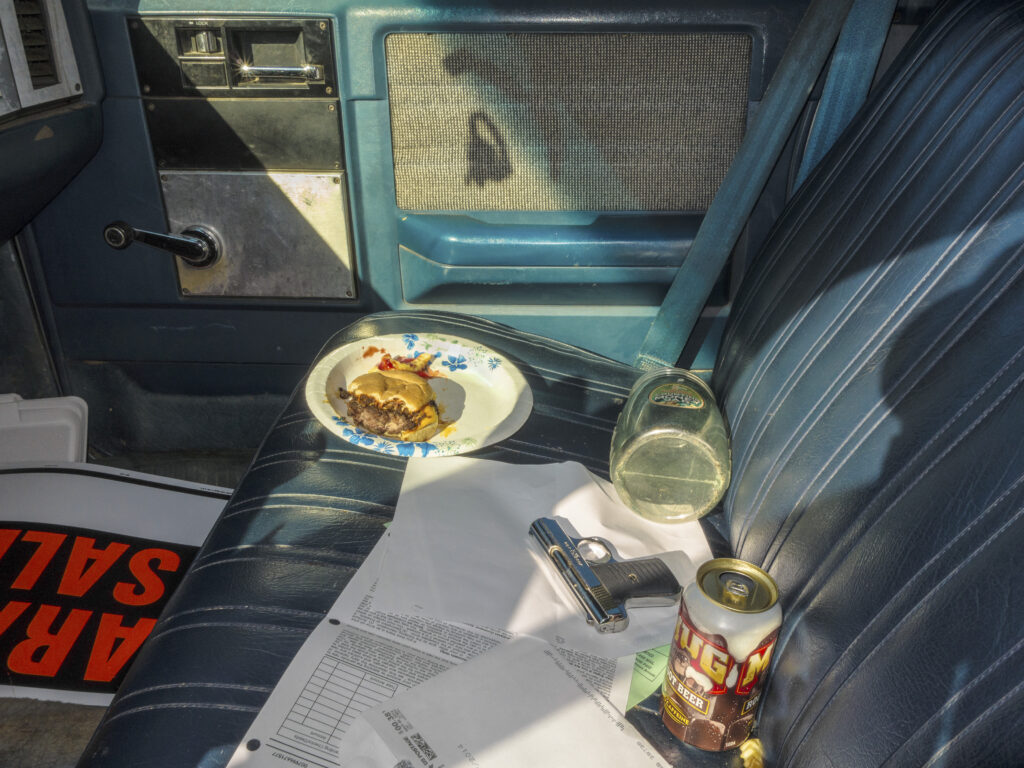

- Menno Aden, Untitled (Car), 2008

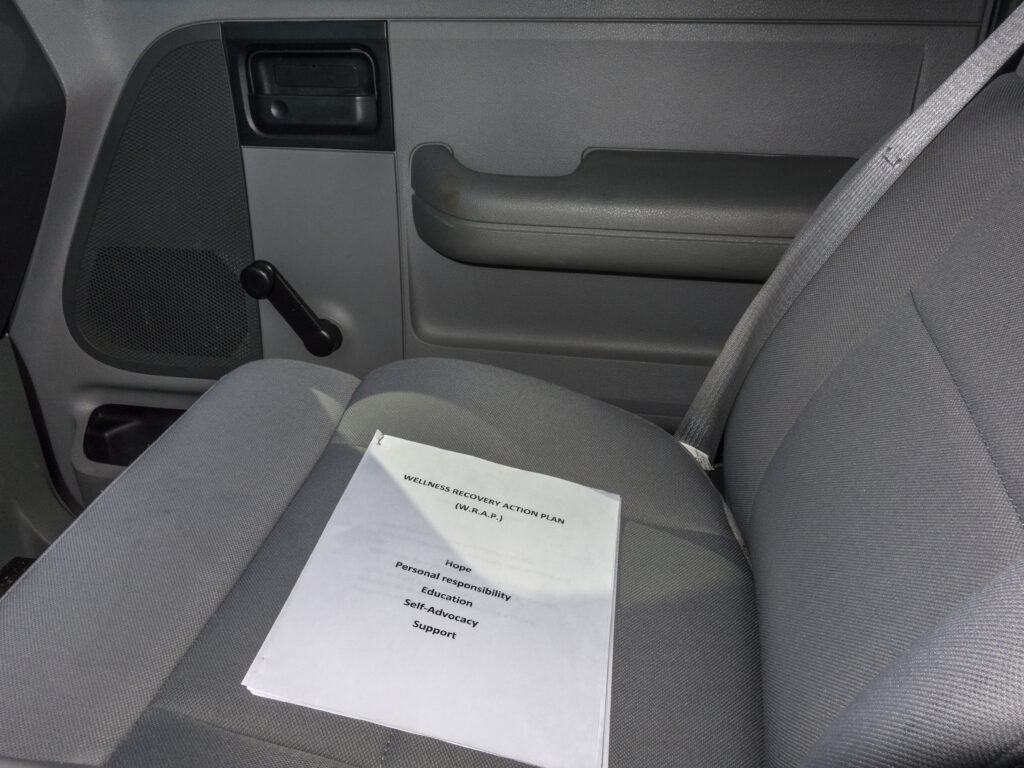

- Menno Aden, Untitled (Car III), 2018

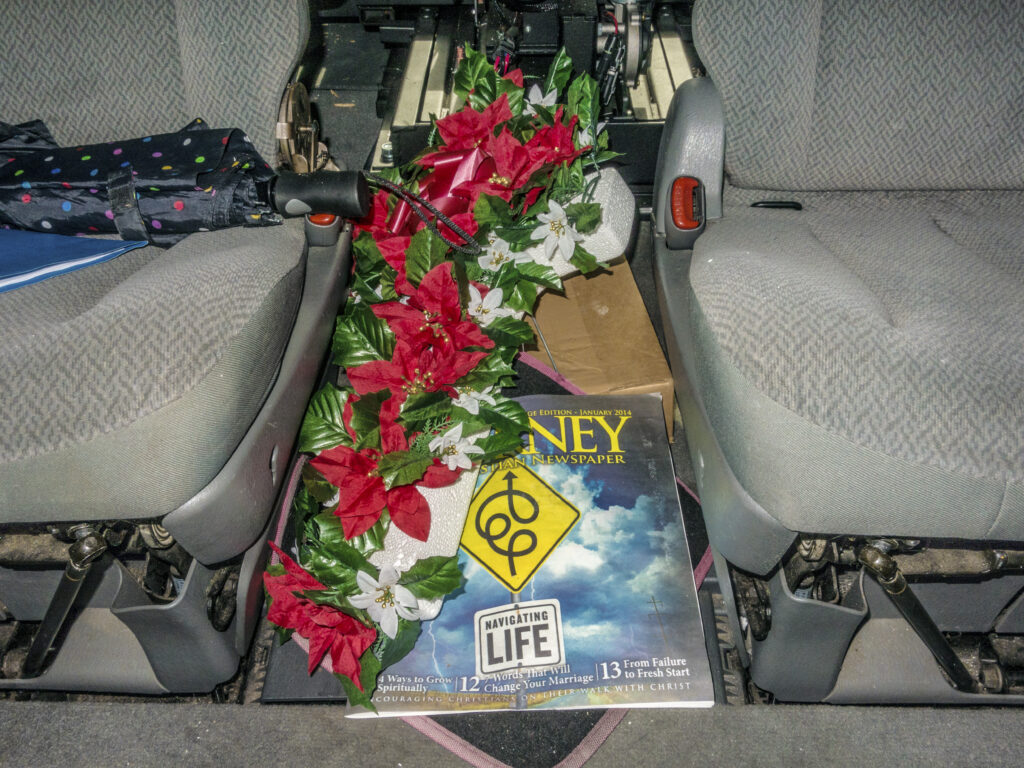

- Menno Aden, Untitled, 2008

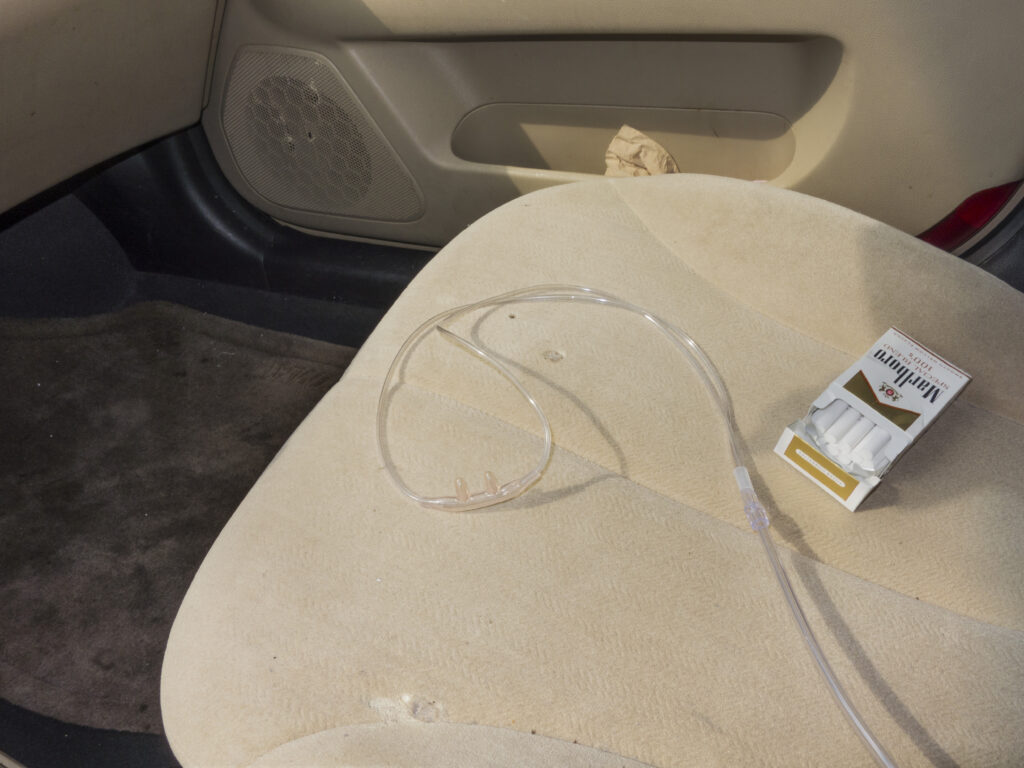

- Menno Aden, Untitled, 2010

- Menno Aden, Untitled (Box I), 2011

- Menno Aden, Untitled (Box VI), 2011

- Menno Aden, Untitled (Basement III), 2011

- Menno Aden, Untitled (Basement V), 2011

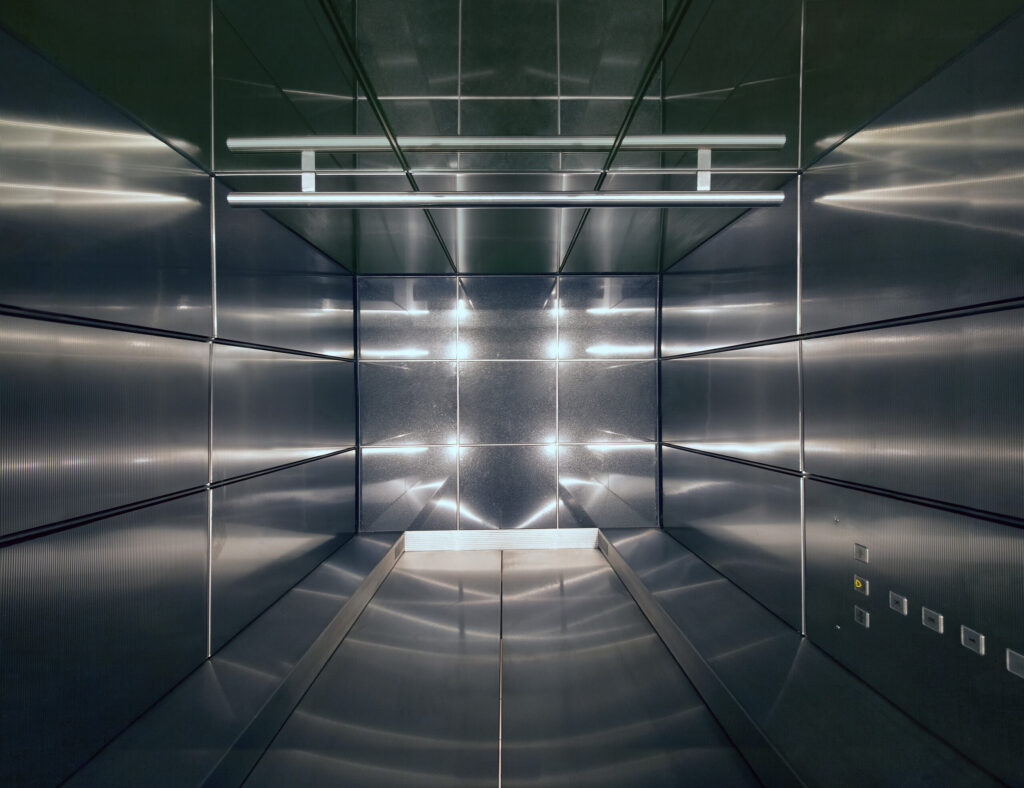

- Menno Aden, Untitled (Lift-III), 2011

- Menno Aden, Untitled (Lift V), 2017

Credits

All artworks courtesy of Menno Aden

Menno Aden (b. 1972) studied Art and Composition at Bremen University and University of the Arts Bremen in 2000. Aden lives and works in Berlin.

Exhibitions include Museu Serralves, Deutsches Architektur Museum, Landesmuseum Emden, Kunsthaus Potsdam, The Wandsworth Museum, London, CMU Museum, Chiang Mai, Thailand, Dezer Schauhalle, Miami, Ratchadamnoen Contemporary Art Center, Bangkok, Institut Francais, Yangon, Myanmar, among others.

Aden was awarded the German Prize for Science Photography, The International Photography Awards, The Accademia Apulia UK Photography Award, The European Award of Architectural Photography, among others.

His work has been featured in The Guardian, Le Monde Diplomatique, Philosophie Magazine France, Der Tagesspiegel, Washington Post, Financial Times Internazionale, Dezeen, Nowness, Ignant, Deutsche Welle TV, among others.

His work has been published in several books e.g. Berlin Raum Radar – New Architekture Photography (Hatje Cantz, 2016), European Month of Photography (Catalogue, 2016), Khao Ta Looh (KMITL Fine Art, Bangkok 2018), among others.

Aden is represented in private collections in USA, Europe, and Asia, including Novartis Collection Basel, KPMG Collection London, Sanovis Collection Munich, Lisser Art Museum, among other national and international private collections.