«I’d like to situate my work within a moment like that, one which teeters on an edge between oppositions.»

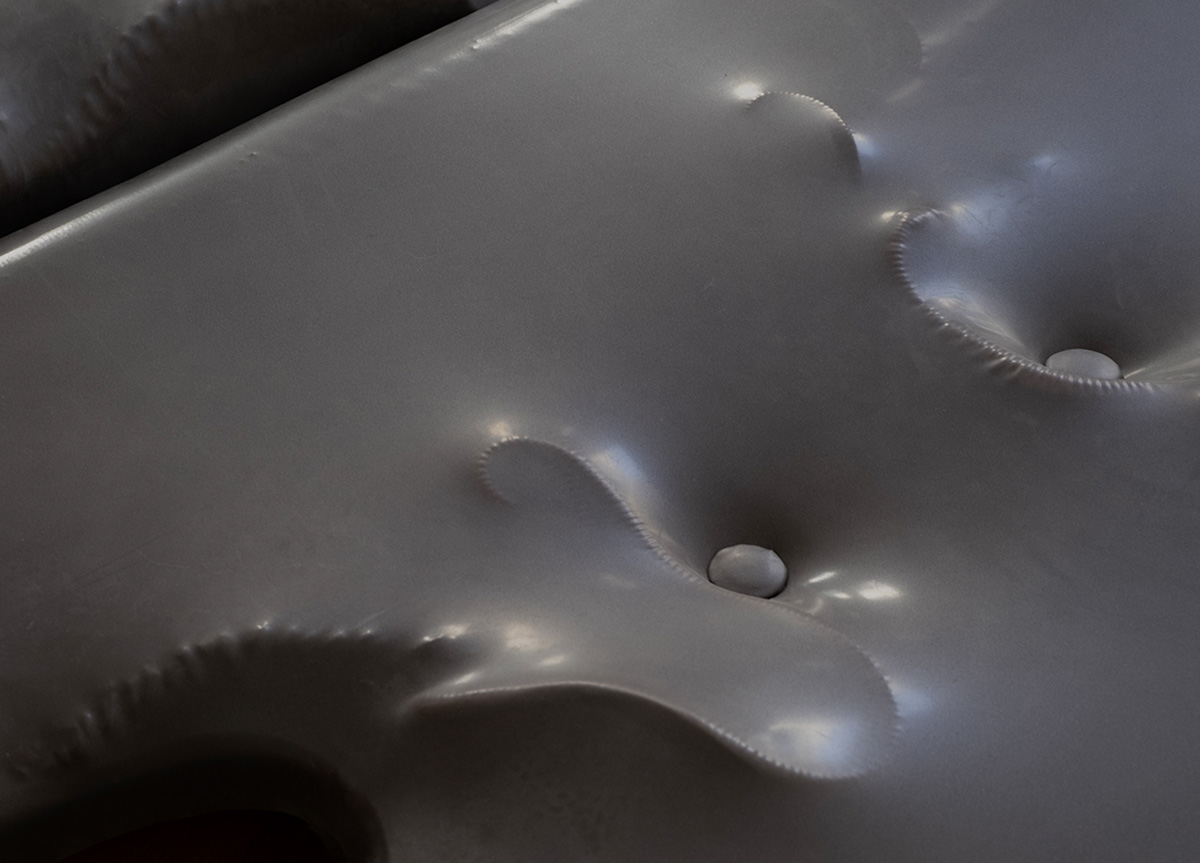

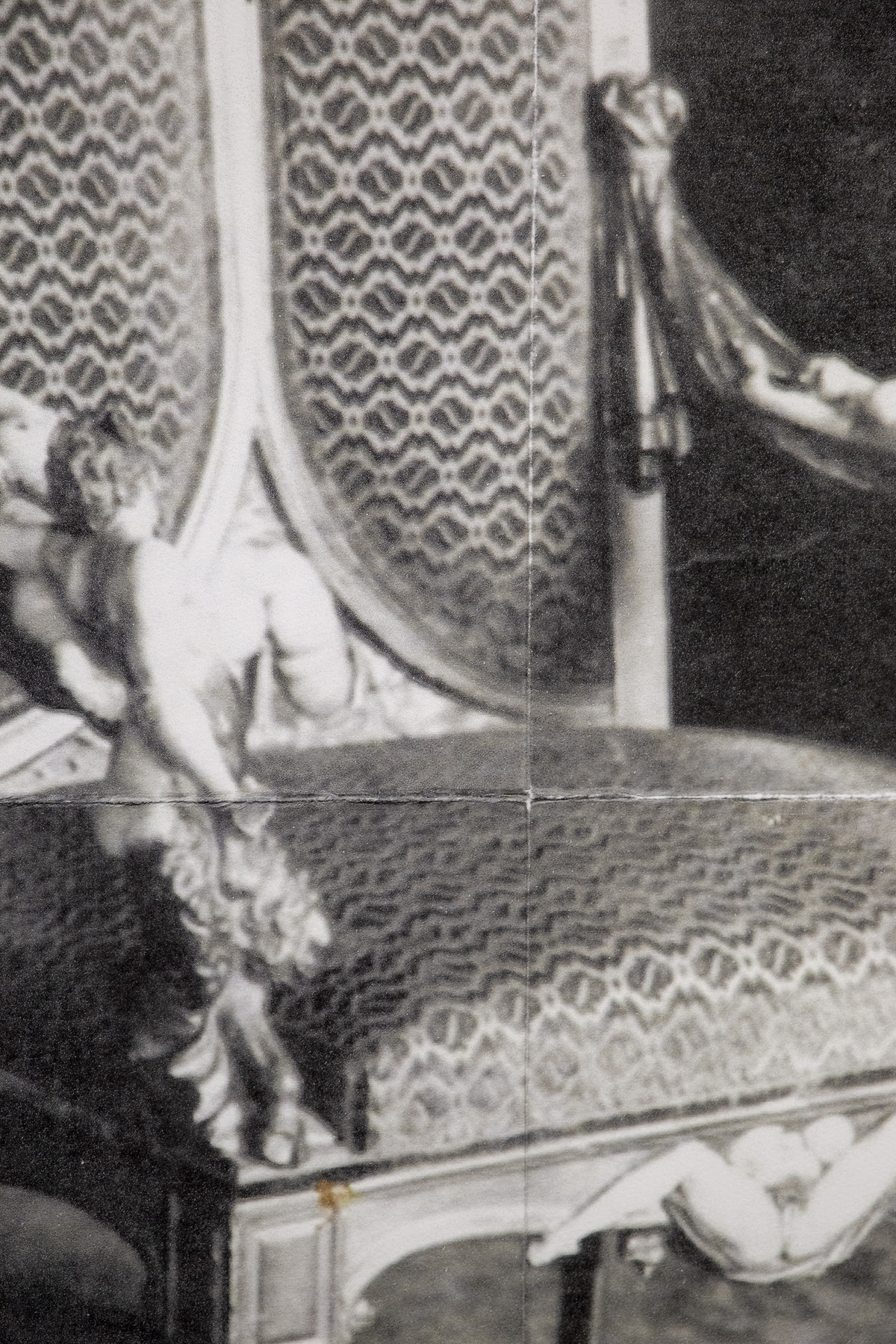

For the artist Laila Majid, exploring the relationship between materials and the body is a recurring theme. Her artwork, Rosie (2019), for instance, is a close-up shot of the imprint of a trainer on the calf of a friend’s leg having been sat cross-legged for a period of time. The markings of the shoe and stitching of the fabric are punctured by the ever-so-slight presence of hair regrowth – the effect is an almost surreal investigation of the similarities between the two surfaces (the now-absent trainer; the skin after wear). Rosie was exhibited as part of the Nude show at Fotografiskia, Stockholm, as well as being selected for the prestigious Bloomberg New Contemporaries show in 2021, with Majid explaining in an interview for the exhibition’s platform that, by “morphing [the body] into a new and unfamiliar form” what we think of as being real is destabilised. That much is apparent in Crease (2021), exhibited at the Slade School of Fine Art MA degree show, in which a black and white photograph of what appears to be a fairly innocuous antique chair, on closer inspection, features erotic mouldings.

The artist is now studying Film Aesthetics at the University of Oxford. It’s a logical step for Majid, who often turns to video and film in her practice – “I’ve never studied film in such a focused way before,” she tells NR over email, “so it’s also helped me to dig deeper into current interests.” In particular, the artist has been “looking into the close-up shot, and the relationship that this sort of shot has to both intimacy and abjection (as facilitated by the camera’s proximity to that which is being filmed).” In previous video works such Macro (2020) and concave/convex (2018), Majid furthers her investigation of the body – animal and human, respectively. In both pieces, the natural surfaces of Majid’s surface (fur, saliva, tongues) take on an almost unnatural quality, creating an interesting counterpoint to the way in which the artist grants synthetic fabrics, by contrast, an organic quality. By turning to a range of materials, mediums and methods throughout her practice, Majid’s work challenges, or distorts, the boundaries of that which we might think of as being diametrically opposed: to that end, how concrete, and how different, are what we think of, or see, as being ‘real’ or ‘alien’?

NR: Am I correct in thinking that Rosie is printed on latex, which makes me wonder how the layering of material features in your work?

LM: Rosie is actually printed directly to vinyl, the printer however uses latex inks (commonly used to produce banners, outdoor signage, etc.) Although the work isn’t printed onto latex, this is a material which I frequently use in my work, and one that I always seem to come back to. I’m interested in the close relationship between latex and the body. It is a stretchy, skin-like material that, in its use as a material of fetishwear, sits directly on the surface of the body, fusing to the form of the wearer in a moment of sweaty skin-on-skin contact. I think this speaks to a layering of surfaces that you bring up. Latex definitely operates in this way; as a non-porous material often used to craft tightly fitting garments, it effectively sticks to and becomes an extension of the body of the wearer, and an extension of the skin itself. Layering, in this case, works to facilitate transformation through dress (change in appearance and physique/sexual release/role play etc.)

NR: What is your process of working with, and sourcing, different materials? And how do you navigate working in different mediums?

LM: Sometimes this is quite an intuitive process, of feeling seduced by the physical properties of a given surface. I also think that it’s important to pay attention to what an image or object may need, be it a specific surface or printing ink. With Rosie, for example, I knew that the image needed to be printed on vinyl given the connection that this material has to window displays and advertising.

«I’ve always felt it important to approach image and surface in such a way whereby they feel bonded or dependent on one another.»

NR: You recently had a joint exhibition, not yet, with your on-going collaborator, Louis Newby at the San Mei Gallery – what does the process of collaboration, more generally, look like for you?

LM: I’ve always been drawn to collaboration given the potential to enrich one’s work through the inclusion of new voices. This was much the case with the video piece in not yet, where we worked with different collaborators who were able to contribute to and elevate the work in various ways, through animation, sound design and AI programming.

NR: And, in terms of your work with Louis Newby, how do you navigate your separate artistic practices to create collaborative work, and a joint show?

LM: Our collaborative practice truly sits in the space between our separate practices. Louis and I have spoken before about the idea that our collaborative work depends on our own practices/individual interests to take shape in the way that it does, and yet does something different to each of our practices as it sits between the two.

NR: Found objects (film, comics, journals) feature in not yet, whilst your Instagram account combines your work, personal photography and other imagery – does the concept of the archive, and the act of archiving, feature in your work?

LM: Instagram is tricky, I can never really figure out how to use it. For now, it exists as a combination of different sorts of images, as you’ve described. I also struggle with the app given its harsh terms and conditions and censorship rules. Instagram aside, images have always been important to me. They feed directly into the work I make and are an invaluable source of research (found images, pixelated screenshots, scans of images from magazines, my own photographs). I enjoy the process of collecting images, perhaps this act of collecting can be thought of as archival. Louis and I also have a shared archive of found images pulled from a vast array of sources which we use to generate print works.

NR: How do you negotiate the human body and other animal forms (real, imagined) in your work?

LM: One thing that immediately comes to mind is the undifferentiated body – a form that points to a potential growth/change/development. I find it interesting to think about how one could present a moment of transformation— how a still image, for example, could hold this moment.

«When does one body morph into another, or suggest a form exterior to its appearance?»

This is something that you often see in science fiction/supernatural horror – for example, at which point does the arching of the spine/contorting of the body tip into an anatomical language that suddenly becomes unfamiliar? I’ve been thinking a lot about [Soviet film director and theorist, Sergei] Eisenstein’s idea of ekstasis in this way, which he explores as a transition ‘to something else’, from one state to another (‘to be beside oneself’).

NR: You’ve spoken previously about seduction and repulsion in relation to beauty – how do these two, supposedly opposing, concepts feature in your work more generally?

LM: I think I focus more on how the two come together, in such a way that they rely on one another to produce a specific effect/affect. I suppose that seduction and repulsion go well together in that their marriage can be used as a tool to reconsider beauty. Pushing oppositional forces together within the same pictorial space also creates tension; it’s a combination which unsettles. I don’t think this is necessarily specific to the seduction/repulsion relationship, but in broader terms I’m reminded of the movement of the body during pleasure- contorted, arched, muscles clenched on the one hand, and giving into total pleasure and bodily sensation in a moment of release on the other. I’d like to situate my work within a moment like that, one which teeters on an edge between oppositions.

Credits

Images · LAILA MAJID

https://lailamajid.net/