Ellen Allien, the legend of Berlin’s club history, has found that cultivating a strong community has been crucial to her creative process and success since the 90s. Her movement is grounded in friendship, emotional support and sharing ideas and resources. While others may seek rapid growth and instant recognition, Allien values patience, diligence, honesty and a touch of eccentricity.

With an unrelenting passion for new sounds, names and ideas, Allien is always on the lookout for fresh talent to add to BPitch, her multi-genre label founded in 1999, or to feature at her ‘We Are Not Alone’ techno party series and releases. As the big boss and experienced traveller, she takes full responsibility for her decisions and avoids spreading negativity to those around her. While she’s open to other perspectives and voices, ultimately, she makes the final call on what’s best for her. All hail the queen of her own life, Ellen Allien.

Ellen Allien is an iconic name in techno culture, and when I hear your name, I think of unending energy. How do you keep the energy going for so many years?

I’m very positive, and this keeps me going. I try my best not to spread negative energy or bring others down. I’m very social and outgoing, and some might see this as being positive or energetic, but it’s mostly because I know what I want and what’s good for me. I’ve made the right decisions for myself, which allows me to be confident and enthusiastic about life.

While travelling and DJing, I’ve encountered many challenging situations, such as not having a hotel, cancelled flights, missing equipment. These experiences have taught me valuable lessons, and instead of complaining about the situation, I focus on finding solutions. I also witnessed the fall of the Berlin Wall in the 90s, which made me realise how quickly things can change in society.

We live among other people, which means certain things are beyond our control. For instance, my assistant could decide not to work anymore, or I could choose to close my company. Sometimes, things happen that we have no control over, and we may not have a solution.

The first thing one notices about you is that you’re very community-oriented. You don’t always need to be surrounded by famous or successful people. You enjoy spending time with those around you and creating intimate and fun initiatives, like the lockdown streaming from your balcony to make things more fun. That mindset is unique in this industry, because people often turn into divas or burn bridges with others when they become successful — but you’ve maintained a sense of community, which is impressive.

I’ve been running my record company since 1996, and we’ve worked with many artists. I’ve seen some really unique and interesting characters, but I’ve found that the craziest people often make the best music. So, no matter how someone may seem, we’re always happy to work with them. As long as the music is great, we are willing to deal with people. One artist told me recently: ‘Oh, Ellen, I do therapy now.’ I said, ‘Yeah, the therapy is good for you and your friends. But you know what? Be careful that your music doesn’t change because you’re a genius.’

So it means you are good at handling chaos, right?

I personally don’t have a lot of chaos in my life, but I do notice other people’s chaos. I try not to let it bother me too much; if I can maintain a normal sleep schedule and feel good, I can handle whatever is happening around me. I know that no one can destroy me except myself. If I let myself become too stressed or sick, then that’s my own doing.

Some people try therapy, and some do other treatments to feel better. Music is healing, and it’s something that I didn’t pursue because it was trendy or for money, but because it’s what I truly love. I’m obsessed with music and have been since I was a teenager. It’s my life. I love my job and I love travelling.

Producing something you love is beautiful. When the freshly pressed records arrive, you check a record sleeve for the first time. When you hold a magazine, you see the pictures and read the interview. When a painter paints an image and it turns out beautiful. You can analyse it and see how you can improve it, which brings you to another level. Being an artist is a beautiful thing because it’s created from your energy. Of course, people have to like it, but even if they don’t, you can still be happy if you love it.

It’s important to know your own tastes and trust yourself. It’s easy to fall into copying others, and it might be hard to be original because there’s so much out there. We all have influences, but if you take the time to analyse and understand how music or other art is made, you can try to create something similar in your own way. Many artists do this, and it can be a fun challenge in the studio. But, personally, I don’t approach creating in this way.

In one of your recent interviews, you mentioned that you don’t like this current trend with blends and edits from pop hits and radio music. It became especially noticeable when the internet culture hit the dance floor after we spent too much time online during the lockdowns. How do you not let the trends that don’t resonate with you affect your approach to DJing?

Playing pop music that everyone knows makes it easier to make the crowd put their hands up for photos and videos, but that’s not what makes a great night for me. A great night is when people dance with their eyes closed or think while dancing, not just putting their hands up to popular songs by Britney Spears or Madonna. That’s the easiest way to have a big audience, but it should be more about finding a way to grab attention by doing proper research. Nowadays, people go online and take stuff they find without effort. They don’t go to record stores anymore, where the person selling records might have suggestions if you ask for something specific.

So, no, I don’t buy this. Maybe those DJs [playing radio hits] are going to grow fast. But they’re not doing anything original, outstanding or fresh.

Time and people have evolved in today’s world, and so has the audience. As a DJ, we hold power to transform everything. We change the dance floor and the music if we take risks and blend different things together. We don’t just come to mix what’s already there. We must take chances. If you’re not willing to take risks, then you’re not a good teacher to me. Building a history or a specific journey is important, even if you don’t want to create something entirely new.

You mean building storytelling in music?

Yeah, a story. I believe that for something to be considered art, it needs to have a story or meaning behind it. Simply playing music from other artists doesn’t qualify as art unless it’s done in a unique and handcrafted way. I love to bring people pleasure through my music. Seeing the audience react emotionally, whether it’s through smiling or crying, brings me joy. My goal is to create an atmosphere where the music takes over and the audience becomes lost in the sound and space. I want to create an experience where people can escape from their daily lives and immerse themselves in the music and atmosphere of the club.

Music is becoming increasingly global, with different scenes influencing each other. For example, many use Baile Funk or other edits of Latin American music in their sets. You’ve recently travelled to Brazil. Did you get inspired by the variety of music there and their unstoppable desire to dance?

In Brazil, there are so many good musicians in the streets and slums, playing drums and making music everywhere. There are so many talented artists exploring new beat structures and so on. The scene in São Paulo is amazing, and it’s growing. The Carlos Capslock Festival was also fantastic, most of the festival goers are Brazilians, everybody is so kind, you can meet so many people and quickly connect with them. It’s super inspiring. I think it’s essential for Brazilian music to grow because Portuguese is more widely spoken than English. This music has to grow, and it’s great that black artists are getting more recognition now. After Black Lives Matter, everything changed, and more black artists are getting bookings now. This has to be the norm. We need Brazilian and South American music worldwide, playing on the radio in England, America and Germany.

You mentioned earlier that you worked with Badsista on a track while you were in Sao Paulo. Is it something new that you will release together?

We went in the studio and both recorded some vocals—she in Portuguese and me in German. We have to see later if we can use it.

I feel like after the pandemic, the techno scene has become more hysterical. Everyone is trying hard and fast to make it happen. It’s just like there’s not so much community spirit from my experience. To me it seems like many people are agitated to make a lot of money in one go. But how do you feel about the techno scene after the Covid?

I don’t have those feelings, at least not with our artist here at BPitch. Maybe at the beginning, some were nervous about paying the rent because prices for everything got very high. But I don’t feel like artists are hysterical because they have shows. Some promoters have failed, but some have become big. Many shows weren’t sold out last year, but now many of my upcoming shows are already sold out.

On the other hand, too many artists want to grow fast because they see others doing it and want the same success. For me, it took a long time to start making good money. I had three side jobs for the first ten years, but that’s not something every artist goes through nowadays. However, you can grow fast if you have the right plan and a good manager. So, if that’s what you want, go for it! I just feel like if you don’t build a community around you, you will not last. I don’t care about those who don’t support or invest time in others. For me, music is sharing and caring. It’s also an intellectual exchange.

To build a community in music, it’s essential to connect with people. You can invite your friends to collaborate on mix tapes or DJ sessions and make music with others as we did in Brazil. Even if nothing comes out of it, it’s still worth doing. This is a movement, and you’re just a little part of it. So it’s important to go with the flow.

If you’re nervous about business or money, people can sense it. They can see it in your face and on social media. Narcissists get anxious easily. They crave attention, money, and success; if they don’t get it, they freak out. They lack empathy and don’t care about building a community. They may create music that pleases the crowd, regardless of quality, just to gain popularity quickly. These people are not part of the true music movement. They have their own agenda and are only focused on their personal gain. Unfortunately, there are more and more people like this, as many grow up without a strong family structure or support system.

Your own parties ‘We Are Not Alone,’ held at RSO Berlin, invite various artists from big names to local emerging talents. Are you planning to get more extensive and international with it, or do you want to keep it intimate in your hometown?

Our approach with ‘We Are Not Alone’ is what I meant by ‘the community.’ We invite artists we love but also ask friends from our BPitch family to play. We try to have a colourful, queer booking. Our lineups are made with love, and we research a lot. We listen to the sets and productions and make sure that the artists we want to present fit our lifestyle. For example, when people run labels, you can see they do something for the movement.

I like how you use the word ‘movement’ and not ‘scene.’

Movement means that there is a big river and we take each other in the right direction. I find this metaphor powerful because it reminds me to create and not get too nervous, even when our governments are stirring up fear. I see this as a radical way to survive in big cities, by not giving in to what they try to put on us and working for small companies instead. By building our own companies and supporting other talented people, we can make our movement bigger and stronger. But it’s not possible to do when you are working with Madonna edits, there are so many other talented singers to work with and reference. Just do your fucking research!

When your Rosen EP came out in early 2022, you started using the metaphor of the mask from the album’s artwork by Erased Memories. Is this about becoming more genuine when one takes off their mask?

When I released the album, I wanted to play more with this alien figure with a gold aura, based on the artwork of my album cover. I then decided to wear masks on my face as a way to emphasise that the image people have of me is not me but a projection of their beliefs and values.

Everyone sees me differently, depending on their religion, education, and other factors. That’s why I feel like I’m a fictional character that people create in their minds. But I’m okay with that, because I understand that people’s perceptions of me are influenced by the stories they hear or the media they consume.

Wearing masks helps me to emphasise this fictional aspect of my persona. It’s like a visual cue that reminds people that what they see is not necessarily the real me. This concept also applies to how I write my lyrics, as I often use metaphors and symbolism to convey my message. I like to keep things open-ended. The sentences in my music have a spiritual quality to them, allowing people to interpret them in their own way and let their imaginations run wild. That’s what makes techno so important to me – it’s electronic music that can allow people to dream and fantasise in their own way. My music is not about me or my message, but rather what people can make of it themselves. While I appreciate punk bands and raw lyrics, I also need music that lets me fly and dream and put my own ideas into it.

I feel like often, because of this escapist and hedonistic side of the club culture, people lose connection to reality and forget what techno represented originally. The idea of escapism was also there, but it was initially about exposing and resisting the world’s injustices and striving toward a more equitable and inclusive future. In today’s techno world, people often lose the connection to the times and places where music was a statement.

Music is still a statement. At least, at our parties, music is a statement. Of course, there’s also the capitalistic side of techno now because promoters want to make money with it. But there are communities in the underground who seek freedom, and by exchanging their ideas, they get stronger. That’s why a club is a place where not everybody should be able to enter.

The community must have space to communicate and create new forms of life. In underground clubs or rooms that aren’t accessible to everyone, people exchange ideas and make changes. They can say, ‘Tomorrow, let’s take to the streets and stage a demonstration, and 5,000 people will join us.’

All of this is created on platforms, whether physical or online spaces, that are not accessible to everyone. The club scene is particularly important for this. I’ve met many people I work with at clubs, bars, and restaurants. These places serve as essential meeting points. They are not just drug dens like some movies portray them. Instead, they serve as platforms for people searching for something they can change.

I hope we can create change together and find people who share our passions, whether in politics, photography, design, or any other field. On the other hand, some people are consumers [of club culture], and they need these spaces as therapy.

We need these experiences to lose ourselves and sometimes to find ourselves again. It’s also a way to feel reborn. However, some become addicted to the lifestyle and end up in financial trouble, and you don’t see them around anymore. They may move to a different place or start doing something else. On the other hand, some creatives draw inspiration from the music and the people they meet there, and it fuels their creative blood.

I’ve met many people who used to have regular jobs but quit to work with creative communities. This transition can happen if you meet a diverse group of people, not just those from your field of study. In Berlin, many people meet at clubs. These clubs need areas where the music isn’t too loud so people can talk, sit and communicate effectively. This is crucial because it’s where many great ideas and collaborations start, eventually leading to art and other creative projects in the city.

Berlin is still attractive for newcomers, but many are complaining about gentrification and how it’s changing the city and its club culture. Local creatives are concerned with rising rent prices and living expenses.

The solution is to start rebuilding Berlin further outside the city centre, where space is still available. It’s up to us to bring our energy and make something happen rather than trying to fit into already overcrowded areas. When I started living in Kreuzberg, it was an underdeveloped area, but someone made it happen. We should remember that and try to replicate that success elsewhere.

In an earlier interview, you once said that in the 90s, when you were starting your DJ career, being a DJ also meant being a freak. To me, it means that being a DJ requires a certain level of uniqueness or quirkiness. What does this ‘freaky energy’ mean to you today?

Like I said earlier, if you’re not different from others, you can’t create music that is truly unique. Having freaky energy is always good when creating music. You can approach music in a mathematical way, and it can still convey a lot of emotion, but it may lack some empathy. I prefer music that’s a little bit dirty and strange rather than ‘clean’ or sweet. However, it’s up to the listener to decide what they prefer, and I think every type of music has the right to exist. Having a bit of freakiness helps to create something new and different.

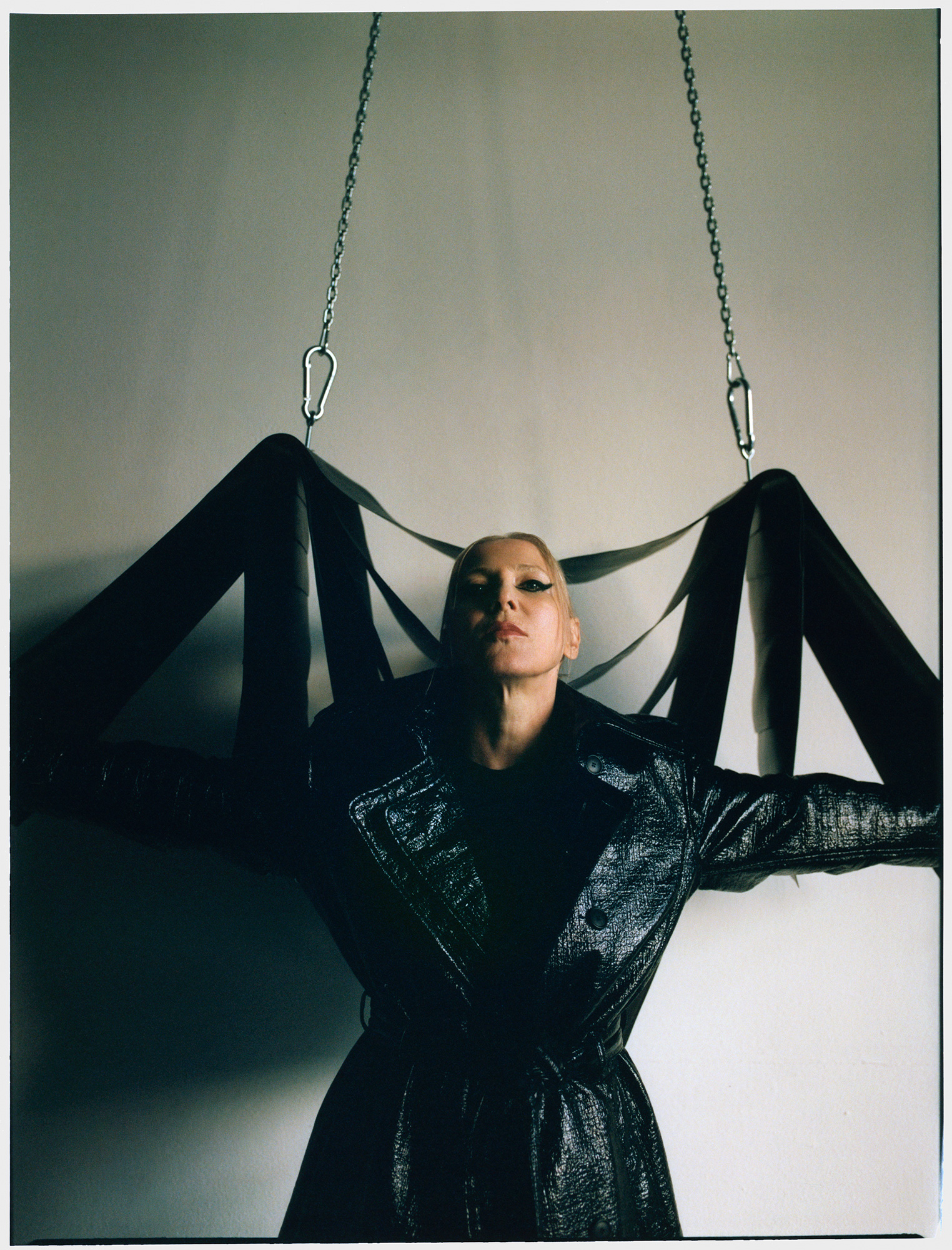

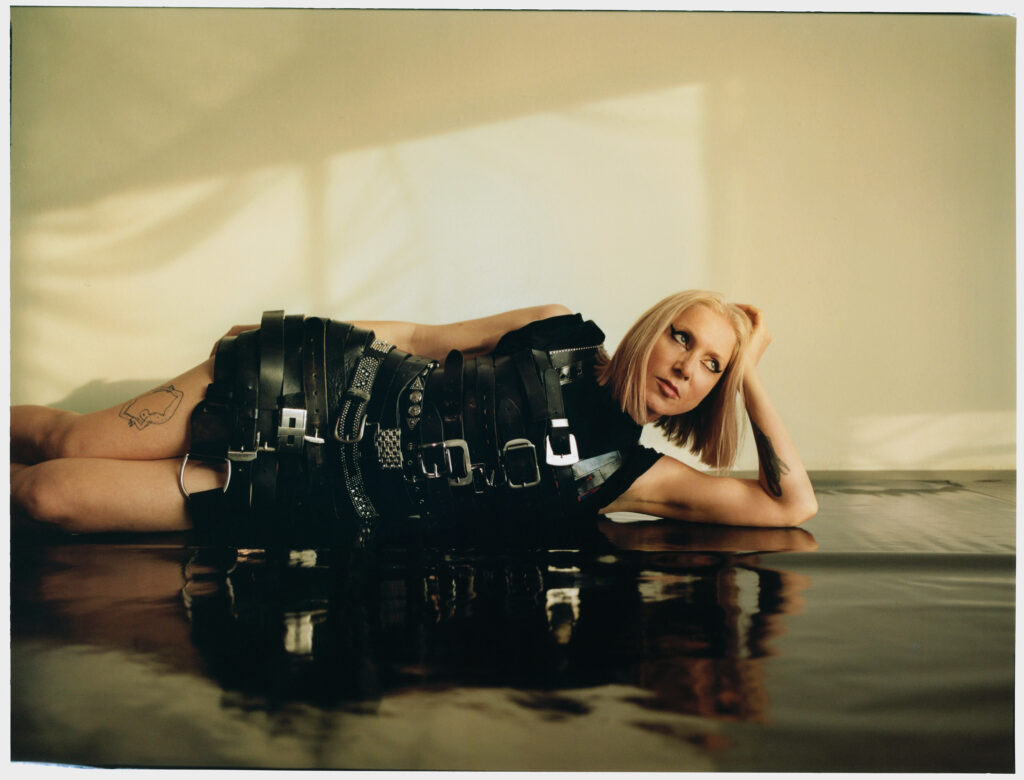

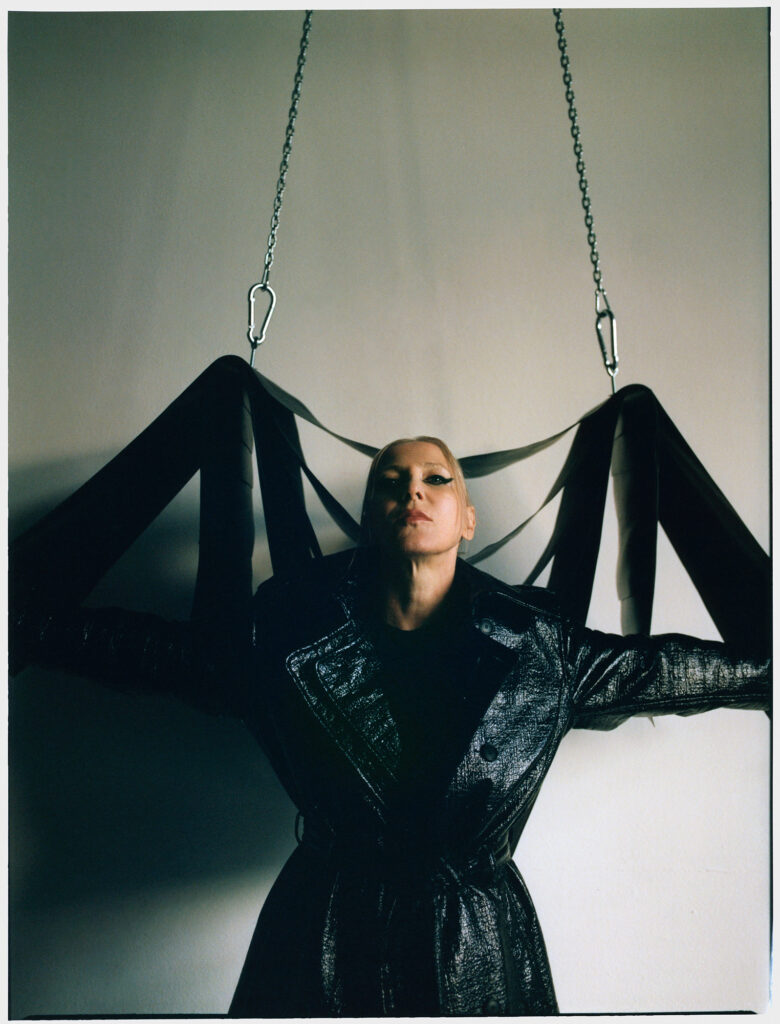

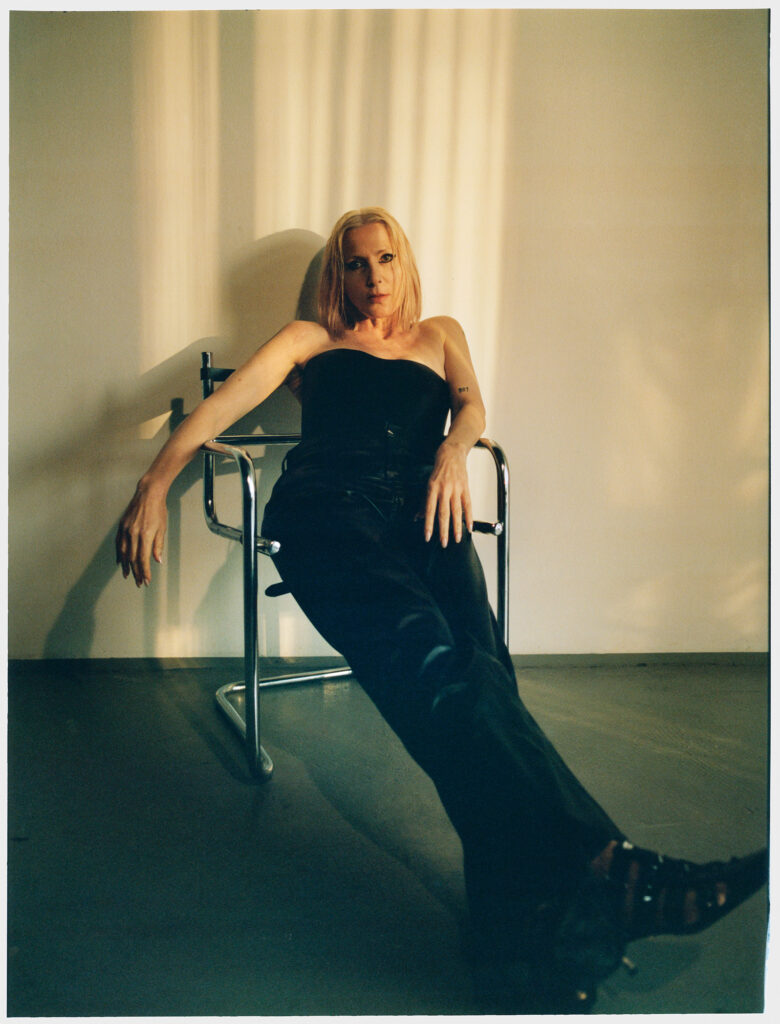

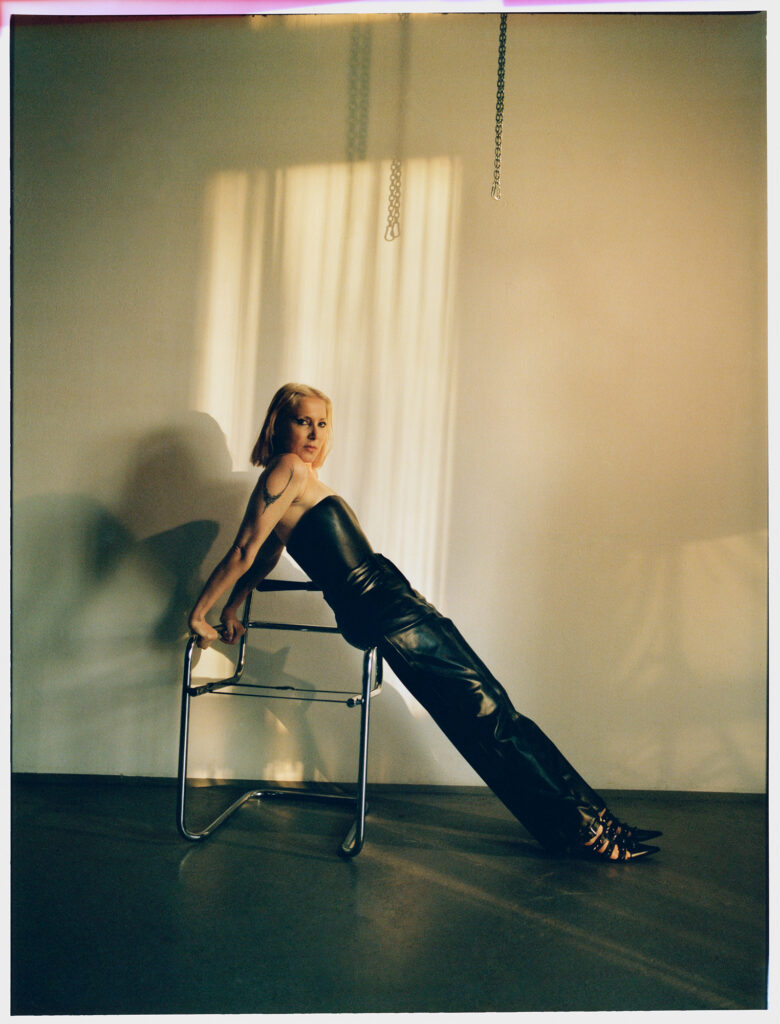

Team

Talent · Ellen Allien

Photography · Nina Raasch

Styling · Fabiana Vardaro

Hair · Berenice Ammann

Makeup · Sabina Pinsone

Set Design · Stefanie Grau

Photography Assistant · Žilvinas Tokarevas

Set Design Assistant · Lars Schefftel

Styling Assistant · Eimoan

Location · Plush74, Berlin

Interview · Mariana Berezovska

Special thanks to Milena Brandy Crow and Melissa Taylor

Designers

- Dress JEANNE FRIOT

- Trenchcoat RICHERT BIEL

- Bustier FENDI, trousers SIA ARNIKA and shoes VERSACE