Emblazoned onto the vast white cube exterior where the Dior SS19 show was held at the Hippodrome de Longchamp last September was a quote: ‘The story comes from inside the body’. The woman responsible for this remark, Sharon Eyal, would also make her mark on the interior of temporary space that was built over the course of two weeks, especially for the show.

Eyal was approached by Dior’s creative director, Maria Grazia Chiuri, to choreograph a dance that would take place as models took to the runway. For the SS19 collection, Chiuri found inspiration in the world of dance; corsets were replaced with loose, tulle skirts, leggings and, of course, ballet pumps. For the performance, Eyal’s dancers weere clad in specifically-designed bodysuits. At times, dancers and models seemed inseparable. If the show reflected the unique vision for which Chiuri has become known for as of late, it also brought Eyal’s enchanting choreography to a new audience.

Eyal founded the L-E-V dance company in 2013 with fellow dancer and collaborator, Gai Behar – whilst the musician, Ori Lichtik, is responsible for the music and sound that accompanies the company’s productions. Performances of the company’s repertoire, particularly OCD Love and its second act, Love Chapter 2, have captivated audiences across the world. In this sense, the Dior show can be seen as a continuation of the ways in which Eyal utilises the body in its totality to convey emotion and feeling. Speaking with Eyal soon after the Dior show, it is clear that this idea that the story comes from within is one that Eyal embodies whole-heartedly.

NR: What inspired the approach you took in choreographing the Dior SS19 show?

Sharon Eyal: For me, inspiration is life – it’s everything I’m going through. I met Maria Grazia [Chiuri], who is an amazing person, and then I saw the work on the collection as it appeared. I think it’s all about chemistry. When you work with people, or another artist, they have to inspire you. In terms of the Dior collaboration, fashion and material is something that I really connect with. It feels like you can see the material sewn into the movement. I really love all the layers that you can see in the connections.

NR: What does the partnership between fashion and dance reveal?

SE: It’s about a collaboration of feelings. I think it’s not just dance, or fashion, I think it shows the combination of something unique that you want to share together. When you create something, it comes from a certain point in your body; I think me and Maria Grazia were creating from the same point, so it was very organic.

“For me, dancing is something basic, like you eat; you dance.”

Life is about movement, and fashion is something that is so free, as if it has no limits. With the combination of fashion and dance, it’s something that seems so distant but very close, like it was growing from the same planes. Everything came together with an organic feeling.

NR: Is dance a medium that can express human emotion better than other art forms?

SE: I think every art form can express these emotions. Painting, cinema, music, and, of course, fashion. But also, something like, going to the beach: it’s all art and it’s all life. For me, there isn’t a difference between life and art.

NR: How does dance reflect art and life back to audiences?

SE: I think dance is something very physical and emotional. Everybody feels these emotions and, and I think that connects people. Everybody feels sadness, disappointment and loneliness, for example.

“There is something about the physicality of the body connects with people: dance doesn’t need to be a story in order for it to be something you understand. It’s emotion as seen through the body.”

NR: How do you hope audiences will interact with the combination of dance with music with lighting and movement?

SE: If the elements are separated, or don’t connect, it doesn’t work because it’s one piece. I think it’s about total feeling and total experience. This connection is important.

NR: When you’re creating a new dance, where do you start first?

SE: I don’t start a piece, it’s always a continuation of something; it’s like the story of my life, but we have deadlines and so, I’m always cutting it, but it’s a long story that carries on. I start by improvising movements, which my dancers record, and from there I cut, edit, and change: this is the first layer. I work with lots of changing compositions.

NR: Would you say that your dances have a futuristic element to them?

SE: I don’t know how to explain movement in words, but it’s very natural and simple, but complicated at the same time.

“It’s about trying to be what you are, in a very, very physical way.”

NR: So are you stripping back the elements of dance to the body?

SE: It’s not just the body, it’s also about the body and soul. I believe in the heart and emotion, but I think that everything comes from the physical, from inside the body.

“Muscles are emotional; you don’t need to put anything on top of the way muscles move because it’s all already there.”

NR: Do your dances take on the traditional structures of ballet, or is it a completely new style?

SE: When you see our dances, you can see the roots of that. I love ballet because I feel like I can play with it; I love the technique, and I love to break it.

NR: In future, do you hope to add another chapter on to OCD Love and Love Chapter 2?

SE: I like chapters a lot, so I would love to add more to that. Anyway, I think it’s always a continuation of what we’re doing, or what we’ve done, so I’m sure it will be happen.

Photos

Ronan Mckenzie’s photographs are imbued with the personal, a quality that transcends the nature of the project she’s working on. Be it personal work or commissions, there’s a warmth that Mckenzie manages to capture regardless. To that end, her recent cover for Teen Vogue featuring Serena Williams feels as intimate as, say, a portrait of her mum wearing the underwear brand Marieyat. It is this approach to photography that makes Mckenzie’s work so captivating and unique.

Speaking earlier this year at It’s Nice That’s series of talks, Nicer Tuesdays, Mckenzie remarked that her desires to pursue styling were quickly quashed upon the realisation that she ‘preferred faces, people and stories’ to clothing. If this explains the beauty of her photographs, then it also points towards the underlying focus that spurs her practise on behind scenes. Mckenzie has taken to task the industries within which she works, exposing and unpicking the narrow vision ingrained in the realms of art, fashion and publishing that still fail to incorporate a broad range of voices. In 2015, for example, Mckenzie’s first exhibition, A Black Body, sought to normalise the diverse possibilities in what it means to be black; a year later, the first issue of her magazine Hard Ears challenged the prevailing obsession with youth culture.

Towards the end of last year, she curated her second exhibition: I’m Home at Blank100, hosted in a purpose-built space with a series of interactive events explored the idea of ‘home’ through the lens of the black experience. At stake in Mckenzie’s work is a critically-engaged, and engaging, approach to shaping of the future – one that is both too enchanting and important to miss.

NR: Your work showcases an honest representation of personal experience by challenging homogeneous representations of ‘black, female, British’; what can the industries you work within do more effectively to counter these approaches?

Ronan Mckenzie: I think the only way to truly be representative, and by that I mean showcasing a diverse cross-section of stories, is to include a more diverse cross-section of people both behind the scenes and visibly.

NR: In the case of both Hard Ears and I’m Home, you have created a platform that wasn’t already available; did you ever aspire to becoming an editor and a curator, respectively, or are these projects that you’ve taken on out of necessity?

RM: I guess you could say I’ve taken them out of necessity for myself, not because any one else made me, but because I needed the platforms to be there so took it upon myself to make them happen. There was never really a moment with either project that I said ‘Ok, I’m going to be an editor (/curator) now’. Those were just the titles that afterwards summarised best what my roles were within those projects. For me, the action part is so much more important than the title, and I was prepared to and excited to take the actions I needed to achieve what I wanted to exist.

NR: What inspires the way you photograph people? Does it change from person to person?

RM: Yes, each person I photograph inspires the way that I photograph them by offering something completely different. I try to capture each person as they are, so that can change drastically depending on the type of person they are and in which way I connect and communicate with them.

“I try not to have a set idea of what I’m aiming to achieve with each person and instead let them lead the way.”

NR: How do you create a sense of tactility and warmth that is present in your work?

RM: I guess that what is visible is the honest sense of warmth and care that was present when the images were being made.

NR: What is the one, most significant thing that you hope to see change in the art and fashion industries in the future?

RM: Artists to be paid fairly for their work every time an institution/brand/platform will value monetarily from it.

Designers

I started with painting portraits. I learned how to mix colours, how to paint skin, fabric and hair. I have always been drawn to abstract painting, though. I experimented, but it felt like it was too soon, I didn’t know how to begin such a process. There’s so much in it. I like the confrontation in abstract work. It’s a good change of focus for me. I like both, very different, processes and techniques. I can get lost in both just as easy. At the moment I’m more focused on abstract work, because I want to explore more, it inspires me to not know where it’s going. For me, painting is the most obvious way to translate an ongoing pace, the world, its people and environment. It’s my language at the moment, it’s always there.

Designers

Space can be seen as a free and borderless. As I searched to fund out how to visually capture an in-between space, a creative process developed. is creative process consists of taking photographs of places and textures, defining forms out of the surrounding and recombining all of it.

I define ‘natural’ as in something you do that feels good, pleasurable, right and authentic to you no matter what the activity might be. When you follow what holds your interest, are true to yourself and do what you really love and what defines you as a person.

To me talent is the successful synergy of passion and soul. It’s something that differentiates people from one another. Talent is being yourself. It’s an ability, a skill set, an expression of a passion that is located in you, sometimes hidden, sometimes more obvious. I think everyone has a certain natural ability, something they are good in without trying hard or even being aware of it.

Talent is something that grows. Something you might need to train through learning about yourself and your passion, being in a right and positive environment, overcome fear and self questioning, staying curious and open minded about your passion – and as a creative – trying to work on personal projects, experimenting and expressing your mindset (visually), no matter how individual or non-suitable it seems to be for the majority.

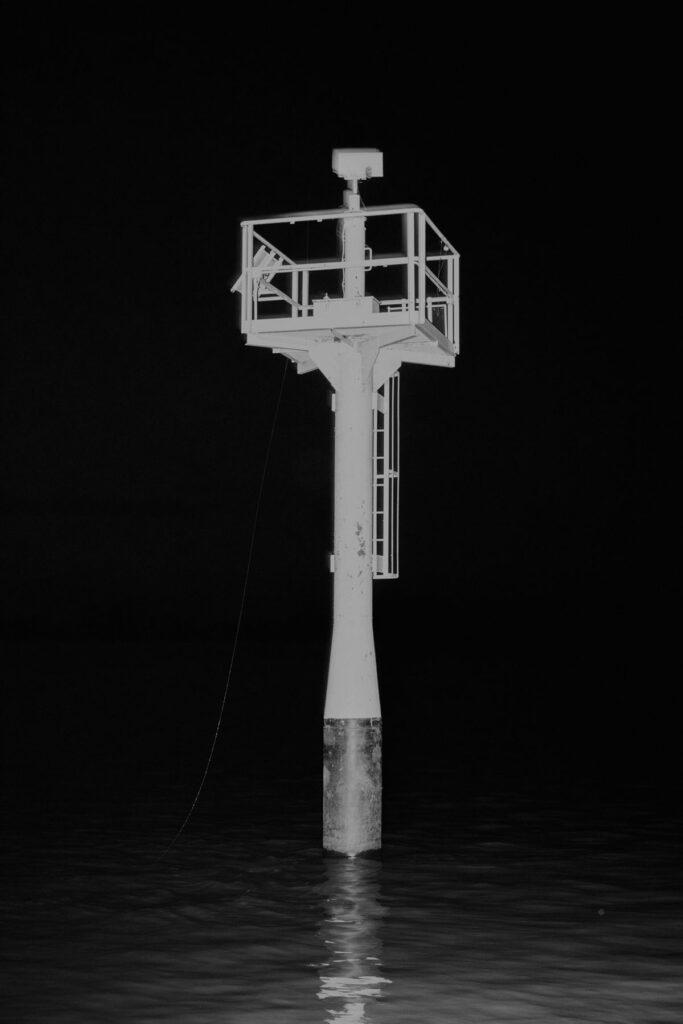

Nocturno is a long term project that spans five years and documents lonely nights across the world. It’s a subjective take on the documentary genre, that serves as a surreal diary

All my life, I’ve been lonesome. Not alone, but lonely. The distinction seems redundant, but one of the most common misconceptions about loneliness, is that it’s a feeling you get when you’re alone. Yet you can be in a room full of people and still feel lonely. In fact, being in company can often heighten the feelings of alienation that loneliness produces, which has been true for me.

Loneliness is a form of disconnection, that creates an invisible gap between yourself and everyone else, like speaking a completely different language that only you can understand. It’s impossible to translate, so it only feels natural to speak it to yourself.

Which is why the night has always been an environment i’ve gravitated towards. Since a young age it had been a source of fascination. I remember i used to sit in the dark of my room at night, looking out the window into my moon bathed backyard. It gave me the strangest feeling, like peeking inside an alternate universe. The trees and grass, acquired a ghostly grey from the soft moonlight, the branches from the top stretched across the sky in the dim light like black lines on top of a black canvas. It looked so beautiful and peaceful. And every night, after i was sure my parents had fallen asleep, I’d venture outside to my park to play under the moonlight. Some years later, and not without a sense of irony, i developed a case of severe insomnia. As a still preadolescent boy at the time, this really had a toll on my daily social life. Since i was hardly sleeping at all, everything during the day became overwhelming, the people, the noise, even the sun light became excessive to my eyes. It was like my brain couldn’t handle it, and i started to resent it. This was something that would ultimately shape the rest of my life.

That resentment slowly built over the years until it eventually led to a complete separation from that daily world. I grew up rambling through empty streets in the after hours, seeking for solace, but longing for contact.

“Nocturno” is the result of these years of lonesome nights. As i’ve navigated through empty cities and towns, fighting against the disarming feeling of being abstracted from society, the night provided me with the context of an empty world, an abstract environment i could shape at my own will and vision. A blank canvas to ultimately create, piece by piece, my own private universe.

Ultimo Paesaggio Siciliano is a visual investigation on Sicily, shot exclusively on iPhone.

It is focused on the symbolisms and clichés that characterise the Sicilian culture, people and landscape.

For Tara Olayeye, whose relationship with her work mirrors her relationship with herself, the practice of film-making has turned into an experience as meditative as it is creative. Her latest short film, So Natural, proves as profound in aesthetic as it is in prose & composition. The visual aspect is only a portion of the young Atlanta-based director’s crafts, as the poem she recites over the film is an adaptation of a song she wrote when she was 18 years old, which she re-appropriated from her archives for the purpose of the film. Her experience with music– singing and playing the piano– reflects in the care she has for the rhythm and pace of a narrative.

The production of this short film was a tough tango between Olayeye and the vintage 16mm camera she swears by. The texture and character of the footage shot on film is true to the attitude of the device. The level of attention and awareness required to shoot with it turned being on set into an undertaking of mindfulness.

Being drawn away from her initial inspiration and expectations, she picked up on the resonance of her own creativity. As So Natural emerged, she found her expectations exceeded by what it turned into, despite coming inches away from moving on from it. Olayeye’s latest project was the fruit of months of internal tides of inspiration which intersected between motion picture, poetry, spoken-word, and music. Patience, with herself and with her work, was of the essence. As she learns to trust her processes, she has been reminding herself not to give into doubt and fear.

Fear forms the roots of many of our expectations, as they manifest a need for security into the future. Figuring out how to let go of them becomes essential to tapping into one’s uninhibited creativity. Our apprehensions are often an architecture of our own mind, and moving forward and beyond them is the only way to embrace reality and discover the multitude of possibilities that may be, both in our work and our lives.

In constant creative expansion, the latest craft she has picked up on is knitting. Amidst the present circumstances, the therapeutic elements of art consist in much more than a practice: it becomes a philosophy and a way of life that nurtures and carries over into everything else.

Olayeye granted NR an introspective insight into her work, distilled below.

Between the visual, the musical and the poetic dimensions of your last film, So Natural, and over the course of the year during which it was shot, what was your creative process like?

I started brainstorming it in January of 2019, I had a concept that I wanted to do – I had a script and everything written out – and actually the final result of that project is not even close to what the original concept was supposed to be. Getting things set up and put together didn’t end up working out the way that I thought it was supposed to. Whenever we were shooting, there were so many mishaps and things going wrong because we shot on 16mm, and the camera that I was using, and still use, is a really old film camera, it’s – it has an attitude, so it was a little temperamental, and there were a bunch of hiccups that ended up happening. As I was trying to piece everything together, when I got the first rolls of footage back in the summer, in the way that I thought that it was supposed to go, it wasn’t working and

“I was almost about to scrap the entire thing, because I thought ‘This is not how I wanted it to be, this is a failure’.”

I walked away from it for a few months and realized “Okay, maybe this project isn’t working in the way that I initially thought, but that doesn’t mean I have to completely dispose of it, I can just re-imagine a storyline, re-imagine how I want this project to feel”. So I picked it back up again around September or October last year, I started re-shooting and I had these lyrics to a song that I wrote years and years ago, I don’t know how or why it came into my head while I was looking at this project, but as I was reciting the lyrics, I thought “wait, this could actually work really well as a poem”. It worked really well with the footage that we had shot over the past few months, so instead of the original script I had, I decided to use the words of that song that I wrote, when I was maybe 18 years old, and that’s where the poem is from. The music is one of my favourite songs of all time, and I emailed the record label that owns the rights to the song to see if I could have the permission to use the song in my project, because I just felt like it fit so perfectly. So that’s the story of the project. It was definitely a very unique experience, that’s not really how I’ve gone about making a lot of my film projects, typically I have a script, I have a very clear vision of what I’m gonna do, and even though things change and evolve, it still holds that same essence of the original concept.

“This project was literally writing itself and I was just there to be as open with it, and accepting of the path that it was taking.”

How did you feel about the way it turned out as opposed to what you initially had in mind?

I’m even more happy with what it turned into. It’s funny because as artists or creatives, whatever you wanna call it, we have– or, I’ll just speak for myself– I tend to have preconceived notions of what I want a project to look like, I’ll think “it’s going to be like this and like that” and the way the project moves, circumstances change, and the project just naturally evolves and what you thought the project was going to be– it just becomes better than you ever expected it to. So that’s always amazing to witness and experience.

It seems like you had a dynamic relationship with this project; how did that reflect with your relationship with yourself?

Last year was really interesting for me, it was a year where I really began to learn more about myself, and I began to realize a lot of negative patterns I had developed throughout my entire life. Patterns of perfectionism, feeling like I needed to control everything, feeling like I needed to know everything, and if I didn’t, I would feel like I was just missing something. It makes perfect sense that this project was my main focus last year, because I did a lot of self-reflection and flowing with myself and, like you said, surrendering a little, and not feeling like I had to control everything and I think that reflected a lot in this particular project because I went into it thinking I knew what was going to happen but then it just flowed into something completely different. It really showed me the importance of being open and not being rigid with my creativity, and understanding that art can in different ways teach a lesson and teach you about yourself, and teach you about life, so

“that project was definitely a reflection of my inner-growth and of being open.”

What made you inclined to shoot this project on film?

I really wanted to learn how to shoot film for the longest time, just from watching other people’s work, watching films that were shot on film, I loved the look of it and I wanted to try it out. I was fortunate enough to know someone who had a film camera sitting in their basement and they sold it to me. It’s definitely a learning curve– shooting on film when we have such instant gratification with shooting digitally– there’s so much we don’t have to think about, whether its just taking a picture on your phone or shooting with a cinema camera. Shooting on film is a humbling experience and it forces you to be very attentive and be really intentional about every shot that you make; you have to be really alert when shooting on film, which I think is a really good practice just in general

What nurture your creativity, and what inhibits it?

For me, patience is the most important thing. I tend to feel restless at times when working through a creative project because it’s easy to care more about the end result than the process. But every step you take while creating something counts for something. So staying with it and reminding myself that the pace that things are going is the pace that is meant to be helps me a lot.

I realize that fear blocks my creativity, I don’t believe [those two states can co-exist]: true creation and fear. You can’t [be fearful] when creating because what makes creating so magical is that you’re letting go of the need to know, you have to trust the process, so it’s interesting how I am a creator but at the same time I deal with a lot of fear. Wanting to create, and Create wholeheartedly, while having these underlying feelings of fears: fear of judgement, fear of failure, fear that things won’t work out, fear that you are wasting your time… It’s an interesting back and forth between creating and fearing.

The main thing is just going with it and within, not thinking too much, feeling my way around. Each creative flow is different but I guess

“the common denominator with each endeavour is being fully committed because I really do believe that as long as I Commit, I really can’t fail.”

When do you feel aligned the most?

I think I feel the most aligned when I’m not in my head. Over-thinking is so exhausting and it’s something that I have a lot of experience with. I feel like even when I’m doing something that I love, if I’m in my head about it, I don’t feel aligned. It’s really important to live outside of my head as often as possible. [While doing] anything like just walking down the street, talking to a friend or eating a meal, as long as I’m present, when I’m actually there, I’ll naturally feel aligned, because I’m not thinking myself into oblivion or panicking about something that holds no real weight. I feel the most aligned with my true nature, who I actually am, my power, all of that; I feel alive and connected to all that when I am actually within my body, doing something with full attention.

Credits

www.taraola.com

www.instagram.com/taraolaa

www.instagram.com/indigoflores