“I love things that make me feel small”

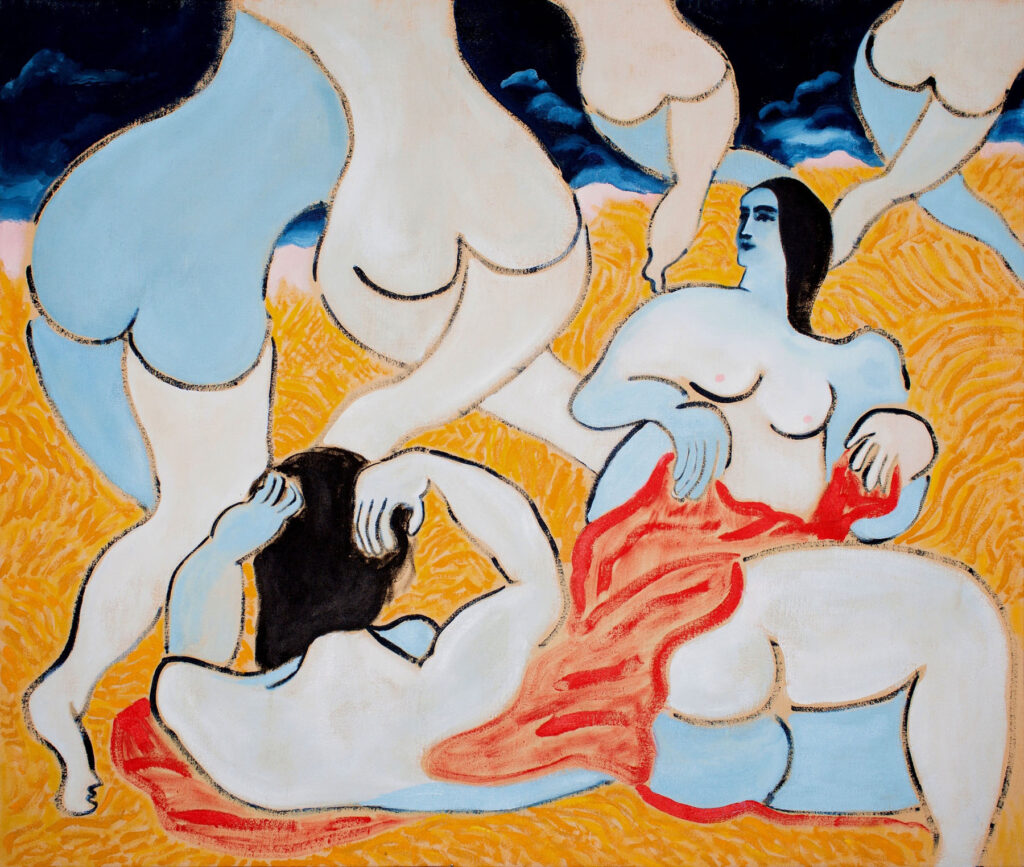

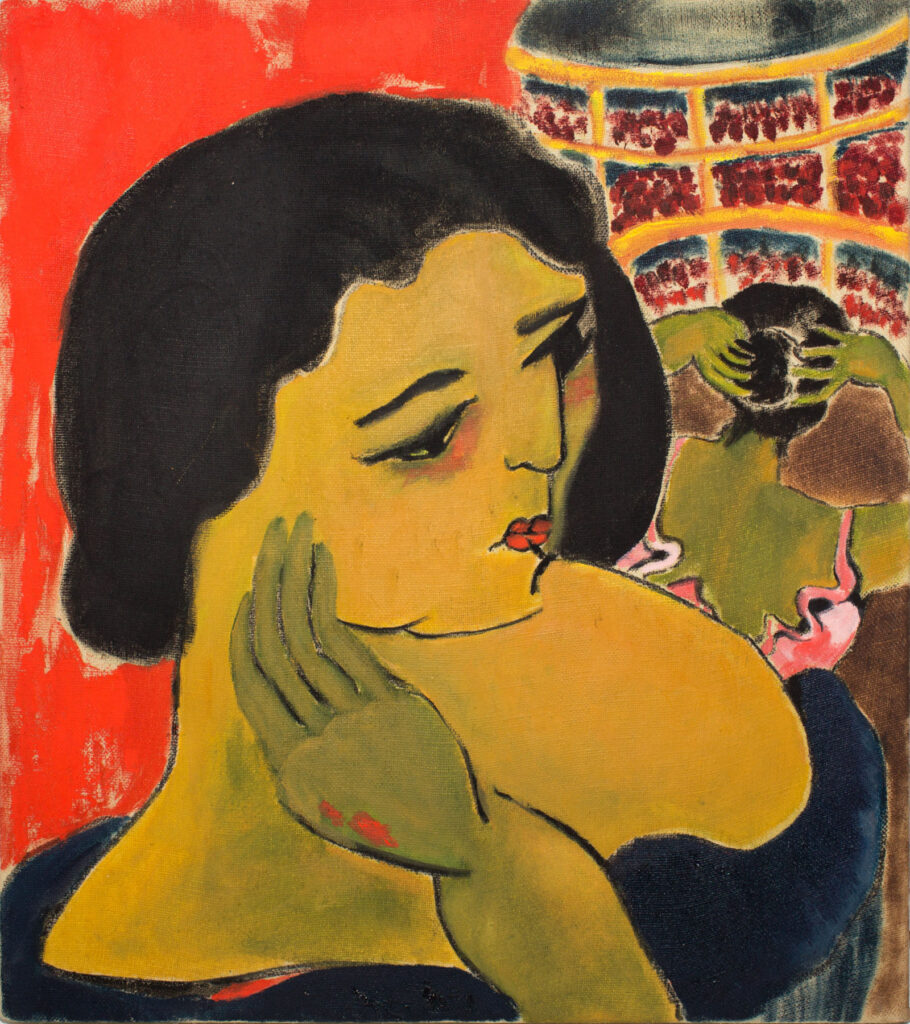

Ever since she was a child, the New York-based art advisor Chela Mitchell has loved beautiful things. ‘I just was in awe of the world,’ she tells me over a video call. Growing up in Washington DC, her exposure to art came via the Smithsonian Museums and there, it was the large-scale works she was, and still is, drawn to; ‘I have a very strong and dominate personality and I love things that make me feel small.’ Vast artworks, towering architecture and huge fashion gowns are what catches Chela’s eye; ‘the drama, the theatrics – everything – that’s where my love for art stems from.’ Art, in whatever form it takes, is a ‘supreme form of self-expression; one of the most important things we get to exercise and experience. You can put something on and tell people who you are without saying a word – and that’s art.’

Chela has been an art advisor for the past two and a half years, launching her company, Chela Mitchell Art, in August 2018, after a career change from luxury e-commerce. It seems quite a leap, but it’s not the first time she’s taken a big decision on a bit of a whim. A couple of years ago, Chela had been working as a personal stylist in her hometown, DC, a city far better known as the bedrock of American politics than a fashion hub. She was styling local politicians and high-level executives, but it lacked the drama and the theatrics that she craved. But when it came to making the shift to more editorial styling, Chela found that she wasn’t getting call backs. ‘I did some research and was like, “Oh – I need to intern!” And I don’t think I’ve ever shared this before,’ she explains: ‘I did the craziest thing ever, and I took an internship in New York for three days, and then had a part-time job at the mall for four days, and I would travel back and forth from DC to New York weekly.’ This continued for a year – a year she remembers well for the B&Bs she’d stay in and crying, a lot.

Ever since she was a child, the New York-based art advisor Chela Mitchell has loved beautiful things. ‘I just was in awe of the world,’ she tells me over a video call. Growing up in Washington DC, her exposure to art came via the Smithsonian Museums and there, it was the large-scale works she was, and still is, drawn to; ‘I have a very strong and dominate personality and I love things that make me feel small.’ Vast artworks, towering architecture and huge fashion gowns are what catches Chela’s eye; ‘the drama, the theatrics – everything – that’s where my love for art stems from.’ Art, in whatever form it takes, is a ‘supreme form of self-expression; one of the most important things we get to exercise and experience.’

“You can put something on and tell people who you are without saying a word – and that’s art.”

Chela has been an art advisor for the past two and a half years, launching her company, Chela Mitchell Art, in August 2018, after a career change from luxury e-commerce. It seems quite a leap, but it’s not the first time she’s taken a big decision on a bit of a whim. A couple of years ago, Chela had been working as a personal stylist in her hometown, DC, a city far better known as the bedrock of American politics than a fashion hub. She was styling local politicians and high-level executives, but it lacked the drama and the theatrics that she craved. But when it came to making the shift to more editorial styling, Chela found that she wasn’t getting call backs. ‘I did some research and was like, “Oh – I need to intern!” And I don’t think I’ve ever shared this before,’ she explains: ‘I did the craziest thing ever, and I took an internship in New York for three days, and then had a part-time job at the mall for four days, and I would travel back and forth from DC to New York weekly.’ This continued for a year – a year she remembers well for the B&Bs she’d stay in and crying, a lot.

She persevered.

“I just really don’t believe in the word no. ‘No’ might mean ‘not right now,’ or ‘not this way,’ but it doesn’t mean you’re not supposed to do this.”

Chela says this with the confidence of someone whose sheer determination to break through into a notoriously difficult industry paid off – securing an internship with Vogue Japan under the stylist, Giovanna Battaglia’s first assistant, Mecca James-Williams. That led to a promotion as second assistant, before she later moved on to work at Net-A-Porter for two years. Looking back on that period, Chela exclaims that it gives her a headache just thinking about; ‘I was 27, you know, it’s pretty old to be interning’.

Why make the transition from styling into art advisory, after all the hard work it took to get to a coveted position that many can only dream of? To Chela, it was simple;

“You know, when the universe wants you to change, it makes you uncomfortable – and that happened to me.”

She was feeling marginalised, underappreciated and was being subjected to racism at work. ‘Every day was a battle, and I just decided it was a battle I didn’t want to fight.’ The industry revealed its true self, and as Chela succinctly puts it, Black women are on the moodboard, but not in the boardroom.

And so, she did something crazy – again – resigning from her job, with nothing lined up other than the belief that she’d work it out. ‘I just kind of jump and figure out the parachute as I’m falling,’ Chela explains. Two days later, she was offered a freelance styling gig out of the blue, enabling her to continue supporting herself and her family. At the time, she had a dream to open a gallery space – an idea that a friend dissuaded her from, suggesting instead to make use of the connections she’d built up in the fashion industry and start off in art advising. ‘That was a Thursday; I had the logo and my website up by the Sunday.

Taking the decision to launch Chela Mitchell Art was, without a doubt, the right one – but it hasn’t always been easy. Chela found herself experiencing imposter syndrome, and questioning who would take her seriously as an art advisor. People don’t listen to Black women, and ‘people don’t listen to dark-skinned Black women, especially.’ In the early days of CMA, when she hadn’t yet gained any clients, Chela was able to appreciate her time as a stylist with a fresh perspective. Where she’d felt so uncomfortable and unwelcome in the fashion industry, she now knew that being in the art world really was where she was supposed to be. And so, when it came down to it, her approach was thus;

“I had to put myself out there, which was hard for me but like, you don’t want to be the advisor that no one’s ever heard of.”

In the two years since the launch of CMA, Chela’s built up a clientele of artists and collectors; clients whose identities she’s very protective of. She tells me of a famous actor that she met at an art event who, after hearing about CMA, asked to use her services; my introduction to Chela came via an Instagram comment left on the feed of a luxury brand, noting that it was through her that the client collected art. I daren’t ask and she’d never divulge, but this much is clear: she’s now had enough exposure to the ins and outs, ups and downs, of the art world and market to sniff out its bullshit.

Central to her practice is transparency; it’s important that everyone’s needs are being met. ‘I have to make sure that artists aren’t being taken advantage of, and to make sure collectors aren’t being taken advantage of as well.’ There’s the risk that a collector’s net worth is only a Google, and a potential price gouge, away – or that a collector may ask for heavy discounts from an artist. Either way, Chela finds it disrespectful, and attributes her maternal instinct to ensuring nobody gets short-changed. In an episode of the Cerebral Women Art Talks Podcast in early 2020, she mentioned not being driven by the money side of the art market; but isn’t the art world more driven by the financial worth of a piece than its artistic value? ‘Now listen,’ she tells me, ‘I like beautiful things. I like luxury and I think it’s very important to know what my ancestors didn’t have, so I’m very honoured to know what it’s like to travel, to eat the best, to wear the best.’ But she’s not driven by money to the point of fucking people over. ‘It’s not my currency at all.’

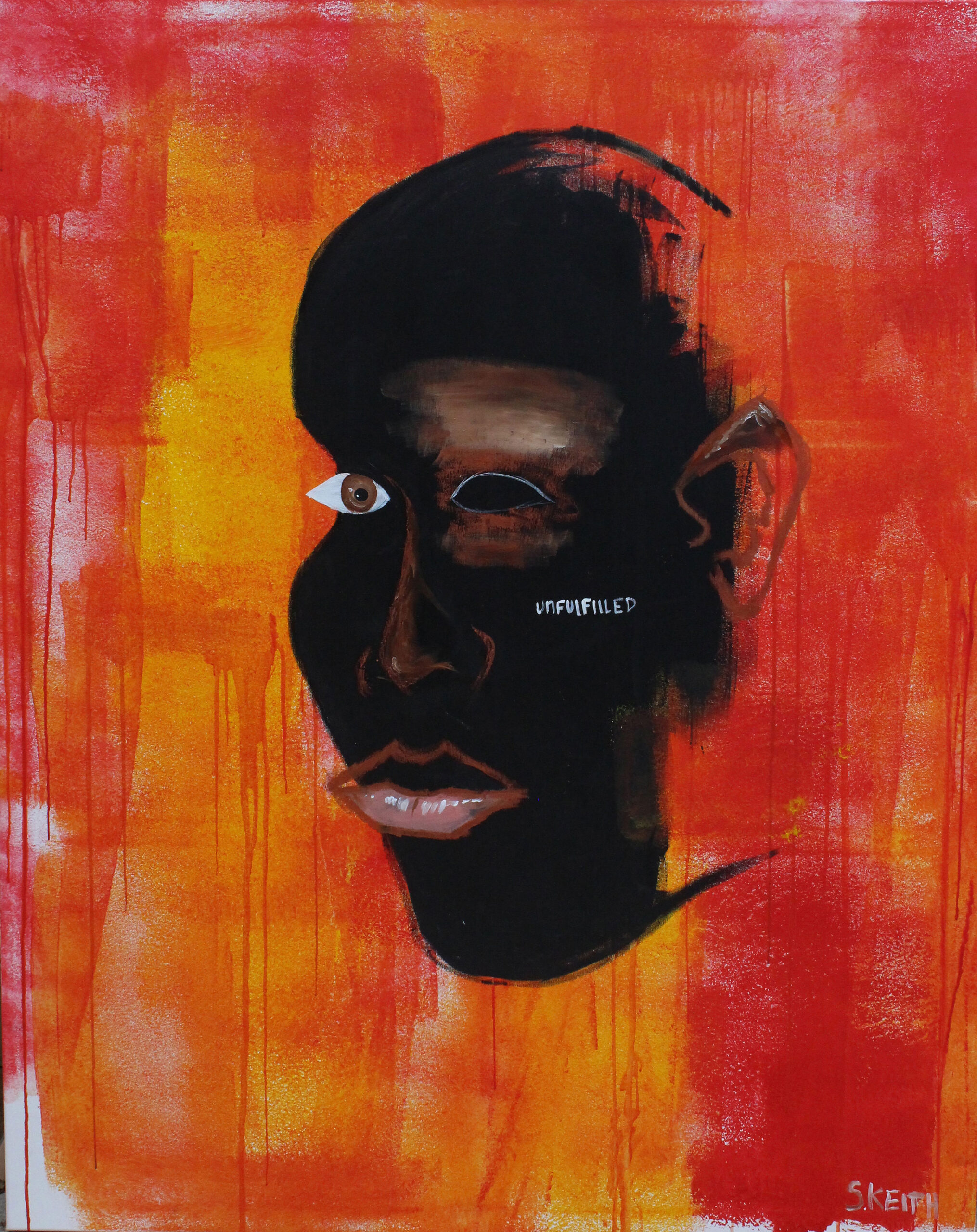

By virtue of working with emerging artists, as an art advisor, selling is part of the territory. A lot of advisors get into the business to sell one piece for, say, $40 million and call it quits. ‘I think it’s very disgusting and that shit repulses me – I feel good when I know an artist has a wire transfer coming their way’. Especially when that’s a Black artist or an artist of colour – even more so when they’re breaking into the art world without the support, or understanding, of the people around them.

“There are a lot of artists whose families don’t believe in their practice or what they’re doing and so, when they’re paid for it, they’re validated.”

To those who think being an artist is not a “real job”, Chela has only one thing to say; ‘it’s a real job, I’ve seen the funds, okay, it’s a real thing. They’re living, they’re sustaining themselves, and what they’re doing is important.’

My call with Chela happened in early August, when the reverberations of the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, and globally, were still being felt. And the genuine heartfelt anguish that was being vocalised and shared throughout the world was met, in various instances, by individuals, institutions and corporations across the art and fashion industry who sought to deflect responsibility by jumping through a series of damage control media campaigns. How did Chela feel to watch the reaction in the art world? ‘I haven’t heard the conversations per se, where people were scared – I don’t think I’d be privy to that information – but I can feel it.’ Or, see it happen in real time: ‘You know, to wake up one day and 30 white women in the art world are following you – are you glad, or are you confused? The number of apologies I’ve received via DM from people I work with is another thing like, should I be happy or am I confused? Even though George Floyd died this year – guys, where have you been? Where were you when Trayvon Martin died? This has been going on since the inception of slavery!’ There is uncertainty in the art world – that much, Chela is sure of – and it’s a good thing.

“I’ve really been enjoying watching the art world have to rethink the way that it operates and ask some uncomfortable questions and explore uncomfortable truths.”

Now, she thinks people feel safe enough to speak out against a gallerist or an institution for being racist or discriminatory in a way that, even a year ago, they’d fear for their career or the threat of being blacklisted. She’s pragmatic though; ‘if it took years and years to build this behaviour, it’s going to take a long time to dismantle it – but we’re starting.’ Chela believes that the real change comes from within ourselves.

If you want to be treated fairly, make sure you’re treating people fairy every day; if you want to be respected, make sure you respect people every day.’ It’s a matter of re-evaluating the way we look at art, and artists – and acknowledging the fact that art is treated as a commodity the same way that Black people were, and are to this day, through the prison-industrial complex. With mass-incarceration, comes free labour.

“When you sell art at auction, do people think about the fact that 400 years ago, Black bodies were sold at auction?”

Chela’s found one way to challenge the stability of the gilded cage that the art world has built for itself – or rather, it found her. As a female, Black art advisor, she’s regularly contacted by young people on Instagram who want to get into the profession. How does that feel? ‘I did not anticipate that, and it just feels wonderful.’ It’s an honour, she says, that people feel comfortable to reach out to her and for that, she’s especially grateful, considering she didn’t have anyone there to guide her into the space she now occupies. One thing she’s keen to address is the mentality that there is only ever enough room for one Black person operating in a space at any time. That’s something she’s witnessed as an art advisor – and she deconstructs the absurdity of that concept by likening in to the ice cream aisle in a shop. No matter how many varieties and brands of ice creams there are in one freezer at any given time, they all have something valuable to offer; ‘Ben & Jerry’s ain’t worried about Häagen Dazs! We’re all put on this world to give something different, in a different way.’

A short profile on Chela and her art advisory was featured in Forbes at the end of last year. In it, she mentions reading an article in the New York Times on the history of a small, but dedicated number of Black art dealers and gallerists who’ve been pushing back against the toxically-white art world for the past 50 or so years. Their contributions to the art community are important, but still, not much has changed; Chela herself only knows around five Black advisors. The article includes an anecdote in which art dealer, Joeonna Bellorado-Samuels, recalls attending an industry dinner where the daughter of a well-known collector presumed she was an artist – the palatable (or profitable?) role that a person of colour can have in the art world. “Art dealer” was her fourth and final guess, compounded by confusion and, perhaps, a tremor of fear.

Earlier this year, Chela launched Komuna House, an art club for people of colour that is everything that membership clubs like The Wing are not. The millennial pink, Instagram-friendly inclusivity espoused by The Wing has, in recent years, been exposed as a distraction from the regular racist, classist and discriminatory conduct that its employees and, alas, many of its paying members, are subject to. ‘I just wanted to create a place where we wouldn’t have to deal with that,’ Chela explains – the programme of events is centred around artists and collectors of colour, and though anyone’s able to join, she wants to be ‘very, very clear’ that Komuna House will exclude the white gaze. She hopes to use the platform to build a community, to foster professional networks between artists and buyers, and ultimately, to ‘weaponise’ members with the knowledge and power necessary to transform the art world for good. Komuna House launched in March, and so it predates George Floyd’s murder; ‘I didn’t know the importance of what I was doing – I mean, I did – but I now understand it differently as the year has progressed.’

To Chela, the artist of our era whose work embodies the powerful potential that art can have is the painter Kerry James Marshall. She describes his work as being ‘brilliant beyond measure,’ in terms of its technical and cultural significance. She recalls walking around his 2017 retrospective, Mastry, with her mouth wide upon, unable to speak the whole time. ‘I’m from south-east DC, and there’s so much shame from being from there’. Through Marshall’s work, marginalised and impoverished communities, like the one Chela grew up around, are given agency. The projects are often depicted as scary places where drugs use, crime and violence are rife; and while Chela contends that those things may be true, there’s a sense of community that’s hard to find elsewhere – communities that come together with all they’ve got to make it work for everyone. Chela’s original plan to open a gallery is something she still dreams about every day, and she knows exactly how the space would look. Of course, 2020 has thrown any short-term plans up in the air for the foreseeable future – but that’s no bad thing. She hopes to have conversations with artists, to get a real understanding of what an ideal gallery should be. As she points out,

“if I open a gallery with the industry’s current business model, how am I creating change?”

What she does know, is that it will be a space for everybody, free from the fear of judgement. There are only so many times you can walk into a ‘very well-known gallery’ for an exhibition of a Black artist, ask for the price list and be made to feel like you’re crazy. At Chela’s gallery, you can be, and do, what you want. ‘And I think that’s why I have to make a space because that’s the kind of energy we need now more than ever.’

Chela Mitchell Art (CMA) provides art advisory to private, public and new collectors looking to navigate the contemporary art market. With experience as a collector and a deep understanding of the industry, Chela is able to assist clients in all aspects of building a fine art collection.

Research and knowledge of the contemporary art world is the core of our commitment to our clients and positions us to help collectors acquire works of art from emerging and established artists. From artist studio visits to auctions, Chela Mitchell Art is able to secure the pieces that our clients need to build their collections.

Credits

Chela Mitchell Art is a member of the New Art Dealers Alliance (NADA).

www.instagram.com/chelamitchellart

www.chelamitchellart.com

Designers

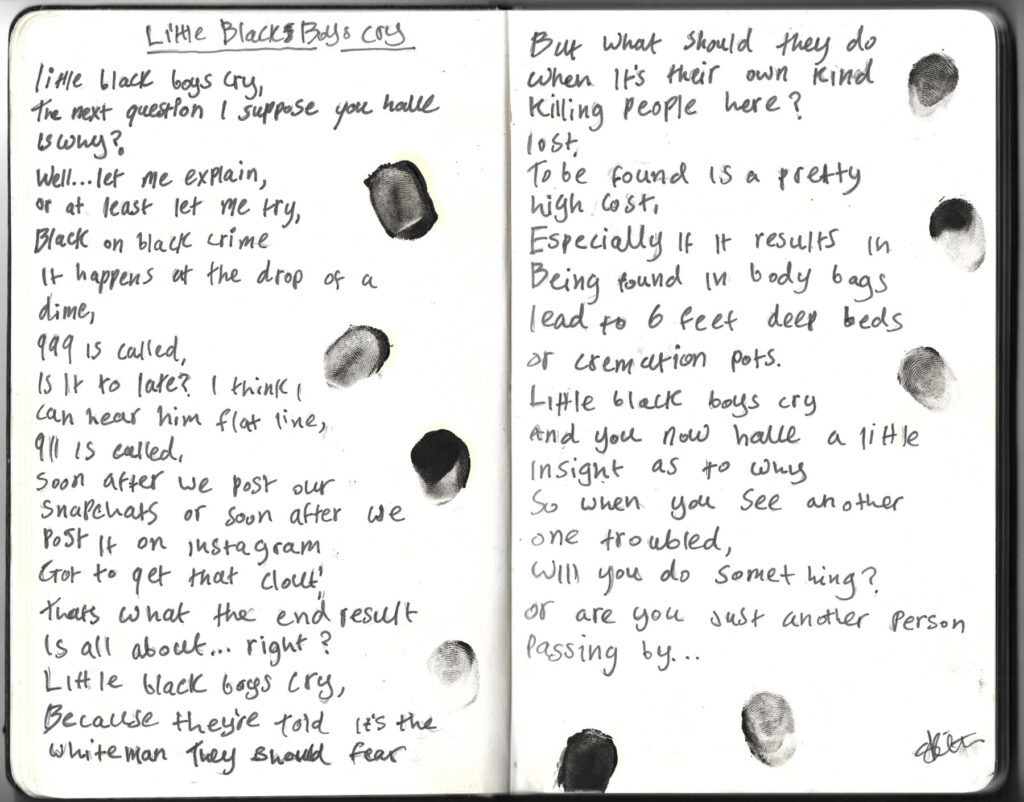

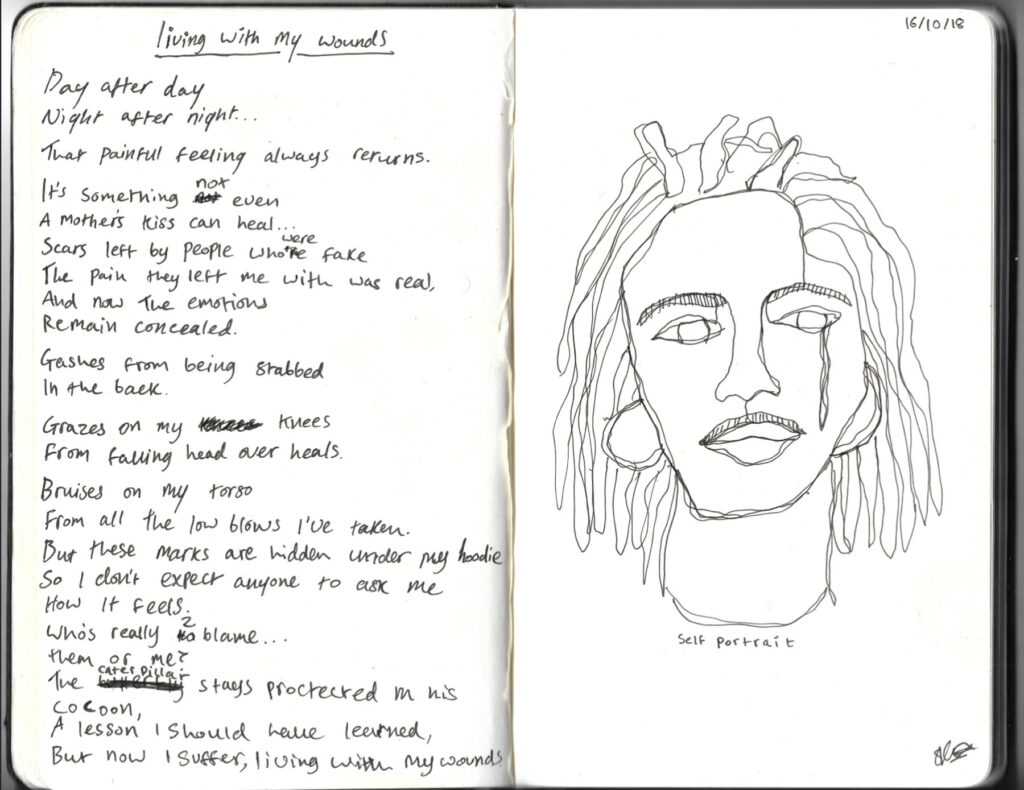

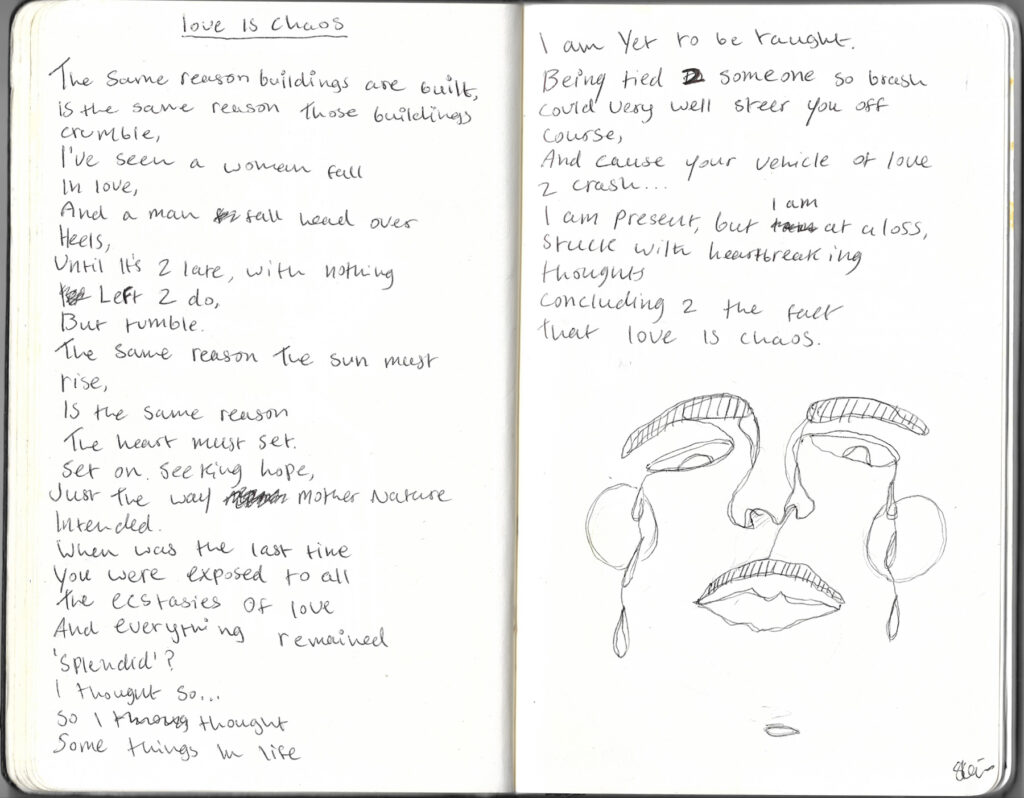

- Lunga Ntila

- Alanna Fields