“No one is really one thing, no one has a fixed identity. I think growing is moving from identity to identity.”

Since the release of his debut album Freudian in 2017, Daniel Caesar has been something of a [crooner redefining R&B and soul of the 1990s with elements of gospel, taken from DC’s upbringing, for a new generation. The album racked up a number of Grammy nominations at the 60th Grammy Awards, for Best R&B Album, Best R&B Performance for ‘Get You’ with Kali Uchis, before winning Best R&B Performance earlier this year for ‘Best Part’ with H.E.R. All by the age of 23 (24 now). Following the release of Caesar’s second album, Case Study 01, in June, he has been on tour since August in the US, and now in London ahead of UK tour dates (sell out) before Europe and Canada.

Earlier this week you reached a billion streams on Spotify which sounds pretty crazy to me. How does that feel?

It feels like good, I don’t think it’s something I ever considered. Like, a million, a couple of million, sounds doable, but a billion is outside of my range of perception.

It’s fair to say you’ve achieved quite a lot of commercial success without being signed to a major label. So considering that, have you got any intentions to expand Golden Child Records in the future at all?

Yeah, there’s always more that can be done. I have lots of ideas, who knows exactly what those turn into, but it’s not going to stop here.

Case Study 01 has a pretty distinct vibe to it compared with Freudian. Could you explain the process and the intentions behind the record?

With this one, I made a few beats first, and it was more about trying to get more complete ideas from my head out into the world, as opposed to writing on my guitar. So this time, some of the lyrics came long afterwards, which isn’t how it usually works for me. I had more to say also, so it’s a lot wordier; I was also being less practical in terms of ‘first verse, second verse’, etc. I was saying a lot more and doing a lot more this time around, and then, trying to organise all my thoughts when there’s more going on that usual.

There was one video you posted on Instagram – a behind the scenes of the recording with an open piano…

Yeah, that was for Too Deep To Turn Back. We got to explore a lot more this time. With the last album, we’d go in the studio and block out a week or less because we already knew what we were going to do. Whereas, with Case Study 01, we started creating the songs in the studio, so we had time to play around and discover new things. I liked that so much more because the studio recording process is when I get to do what I want, it’s like my favourite part. So, this time, we were at Abbey Road Studios and just fucking around with all the cool stuff, and we just stumbled across this sound we liked and found a part for it…

You’re commonly referred to as a crooner, a romantic, or like a present-day D’Angelo, is that something you ever anticipated? Or is that a strange thing to be?

I mean, I guess, yeah. Singing was always my thing at school. I was always the crooner guy, that was my shtick or whatever… That was me, I could sing the emotional songs…

Did you always want to pursue singing?

It was always one of the things I wanted to be, not the first thing, but one of. When you’re little and you tell adults, well-meaning adults, what you want to be, they try and help you manage your expectations… It’s like, chances are you’re not going to be able to do it, in the nicest way, and so you try and realign, and pick something more practical. So you try and fit into what you think you’re supposed to be doing, and then you’re just not good at that. And so, it always came back to singing.

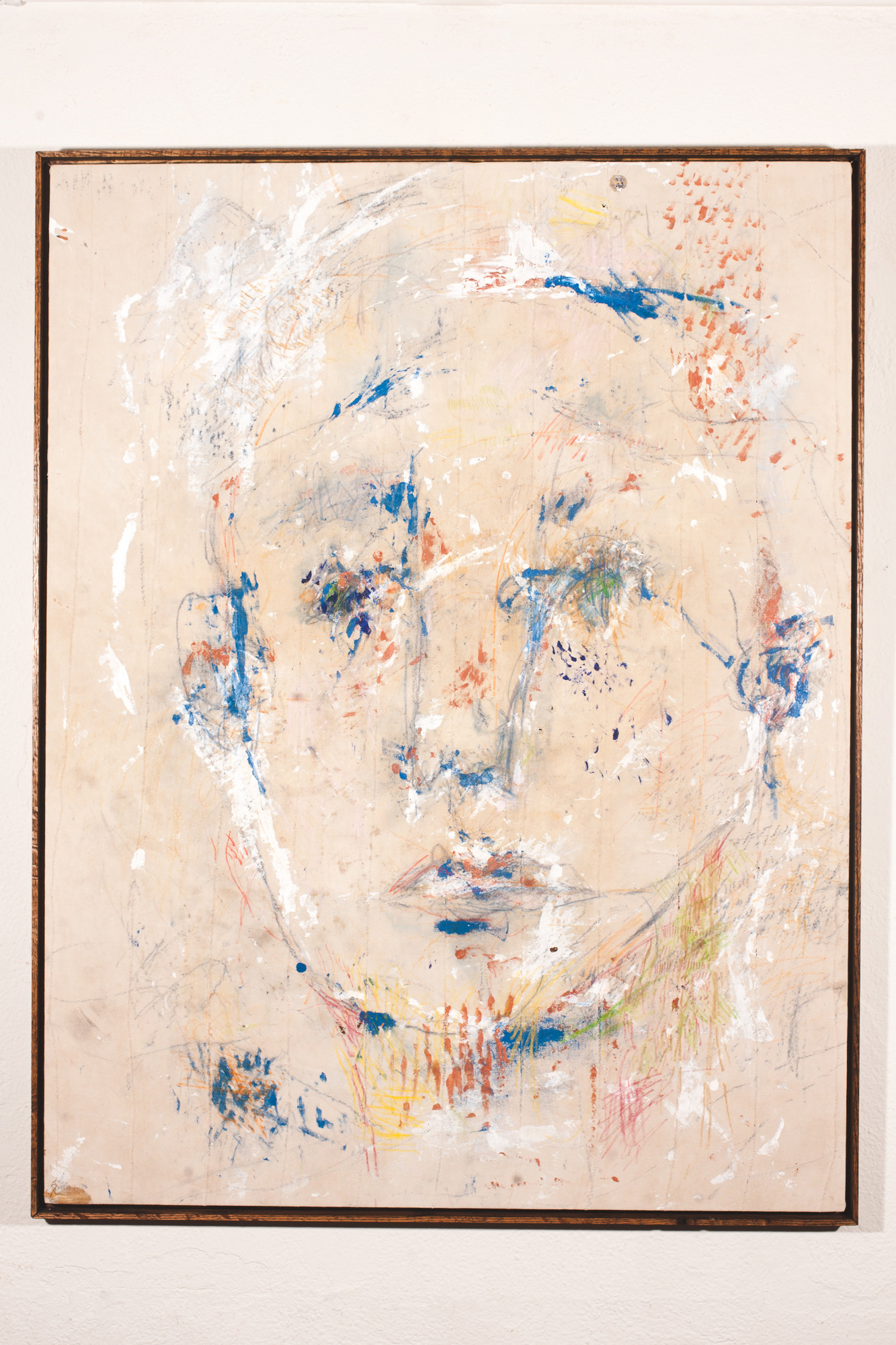

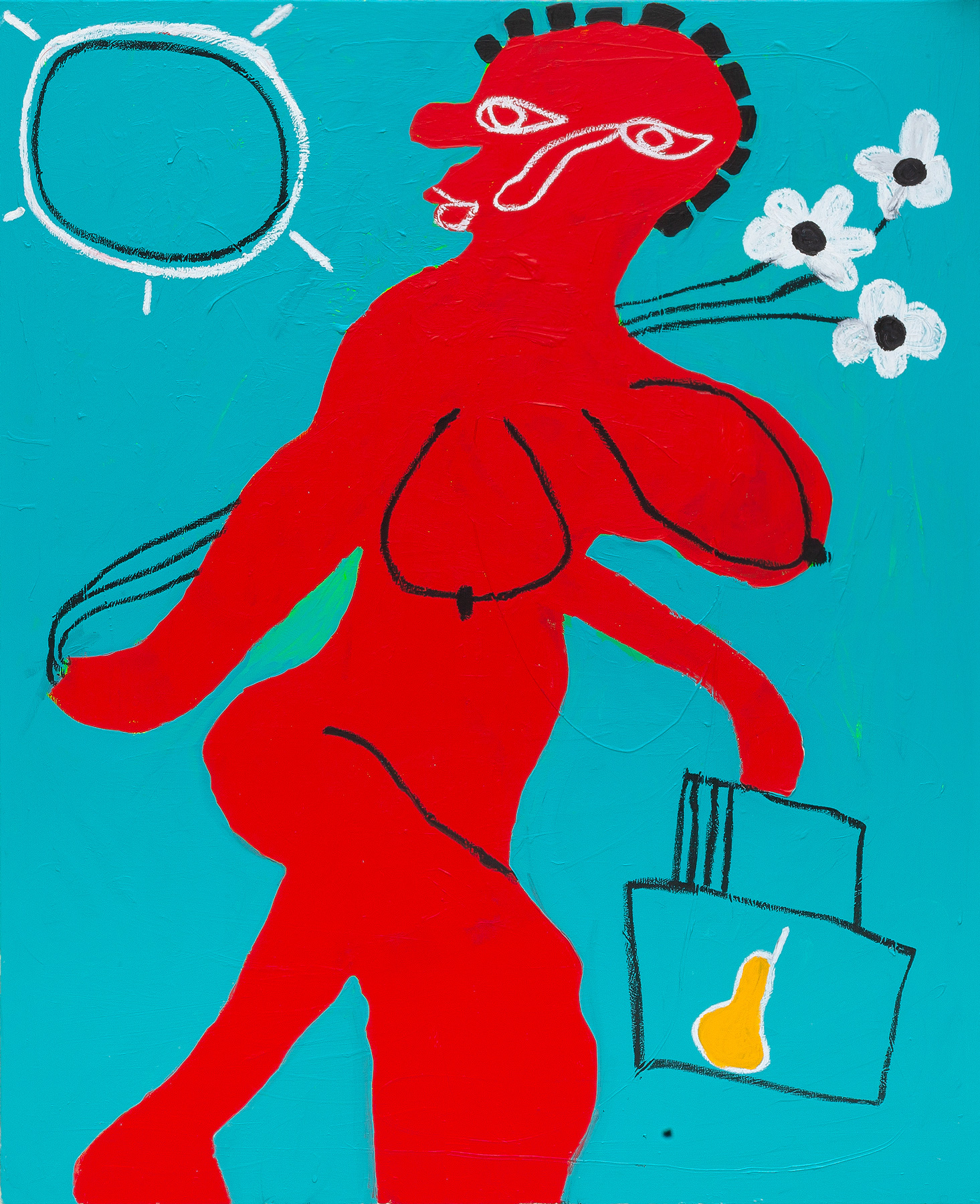

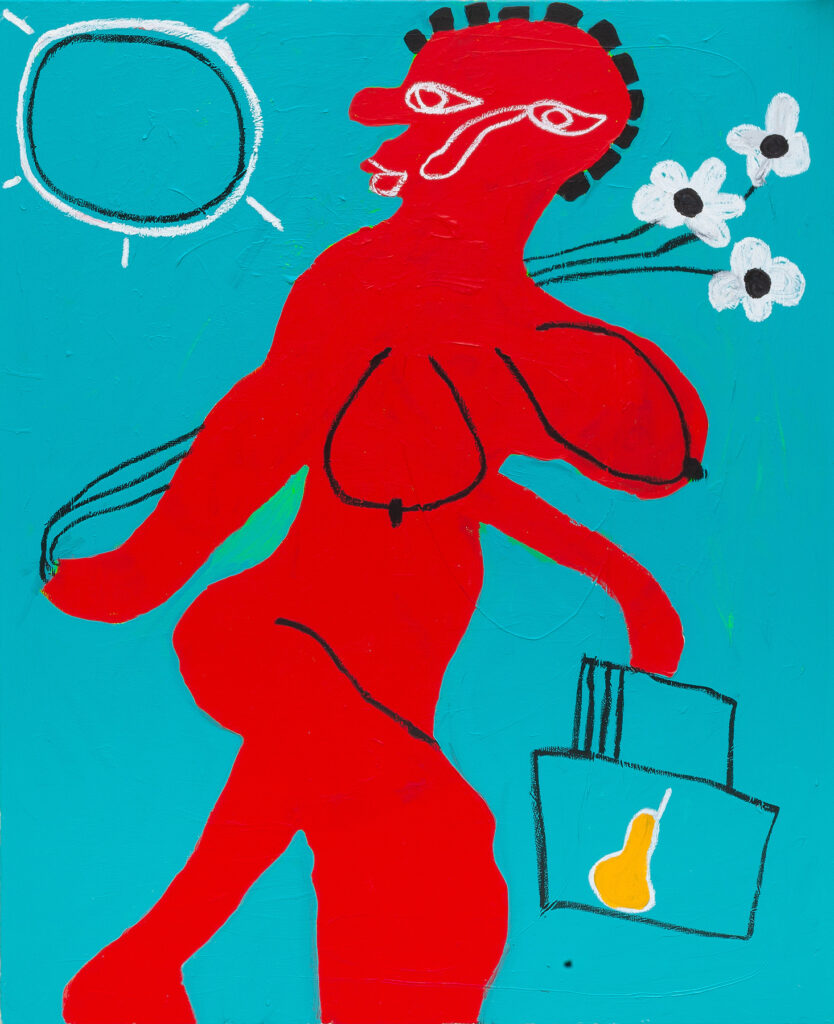

Something that is striking about the visuals for your albums and videos is of you as what seems like an isolated figure (especially in the spacesuit). Is there anything in that?

When you say it, it makes sense to me, but I don’t think it was intentional like, ‘let’s do this’. I was just feeling isolated or, trying to connect, but being unable to, you know? I’d say one of the themes is about wanting love, wanting a connection, and it’s always fleeting or unrequited.

There’s a moment in your conversation with Brandy where she remarks that you’re a great storyteller; How important is storytelling to you as a songwriter?

It’s important, but I don’t think it’s the only tool necessary. I think the most important thing is conveying the feeling, whether or not you’re being descriptive and articulate, whether you’re retelling a story, or you’re just saying what’s need to be said to convey the idea or the feeling. I think storytelling is important; it helps make things more rhythmic. But the feeling is the most important thing, however it is you get that across.

You mentioned that, with this album you didn’t write some of the lyrics until afterwards but, with songwriting, where do you start and what’s your process?

It usually doesn’t come ‘til I’m in a really good mood or really bad mood. Or, say, I have a conversation and I hear a phrase that I like, it’s usually something that sounds paradoxical. Just something clever. Then, chords might come and surround it. It always come through extreme emotion, energy and excitement. Usually, honestly, I’ll be in the shower and I’ll like, drop everything and do the voice note. Sometimes it turns into a song, sometimes it’s just a short little note and I’ll send it over to Jordan [Evans, Caesar’s manager] and, he puts it in a folder with thousands of others…

What does ‘reinvention’ mean to you?

Reinvention is death and rebirth. No one is really one thing, no one has a fixed identity. I think growing is moving from identity to identity. I mean like, what I’m doing is the extreme art version, where I’m an astronaut [for Case Study 01]. But, it’s about growing through your life, finding new parts about yourself and taking it on fully.

How would you relate reinvention to something that you’ve gone through or that’s happened to you specifically?

I think everybody is the way they are because of things that have happened to them, so there’s no one moment I can think of… But, through trauma, through the good things and the bad, these things chip away at the sculpture that becomes the final ‘thing’.

Team

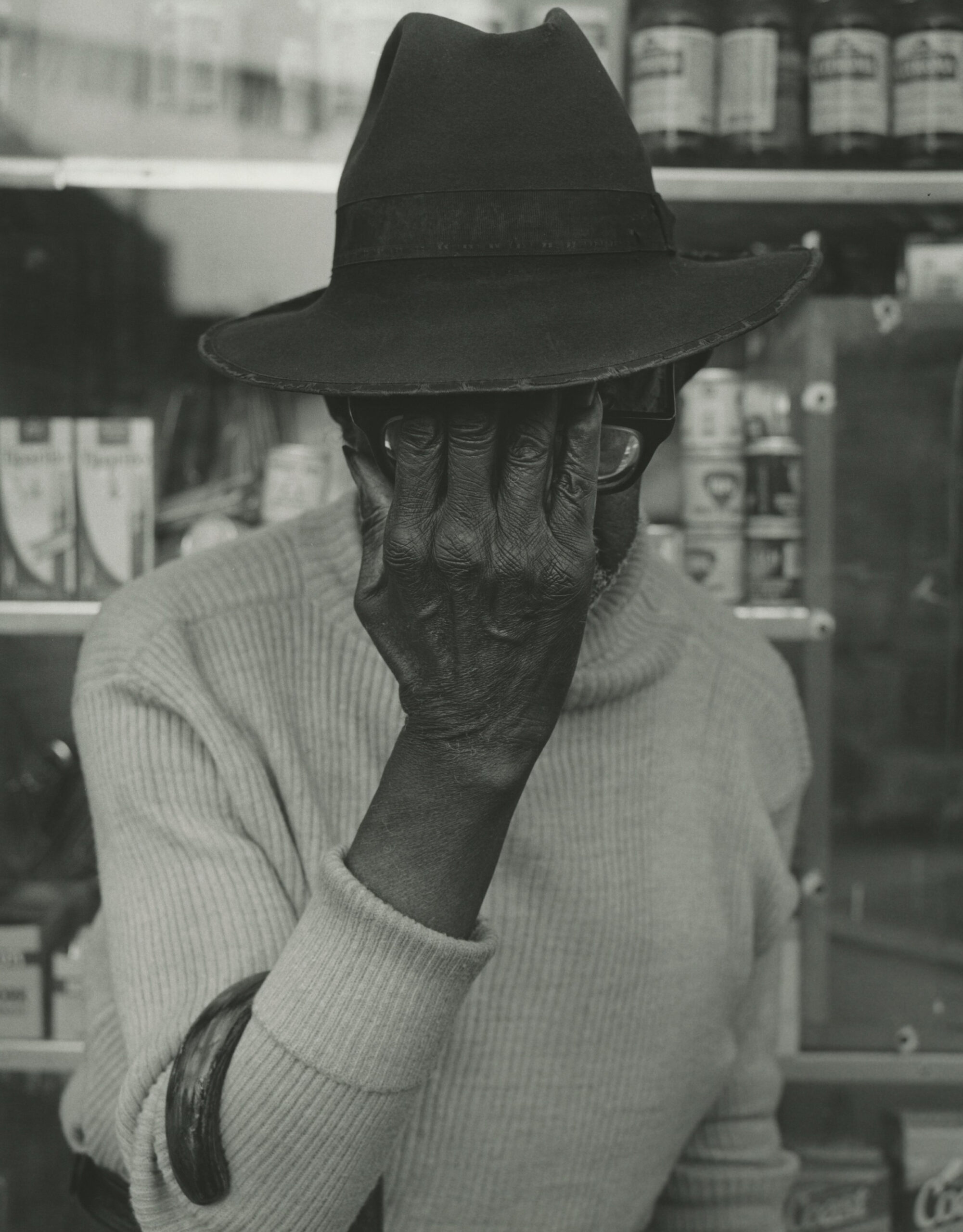

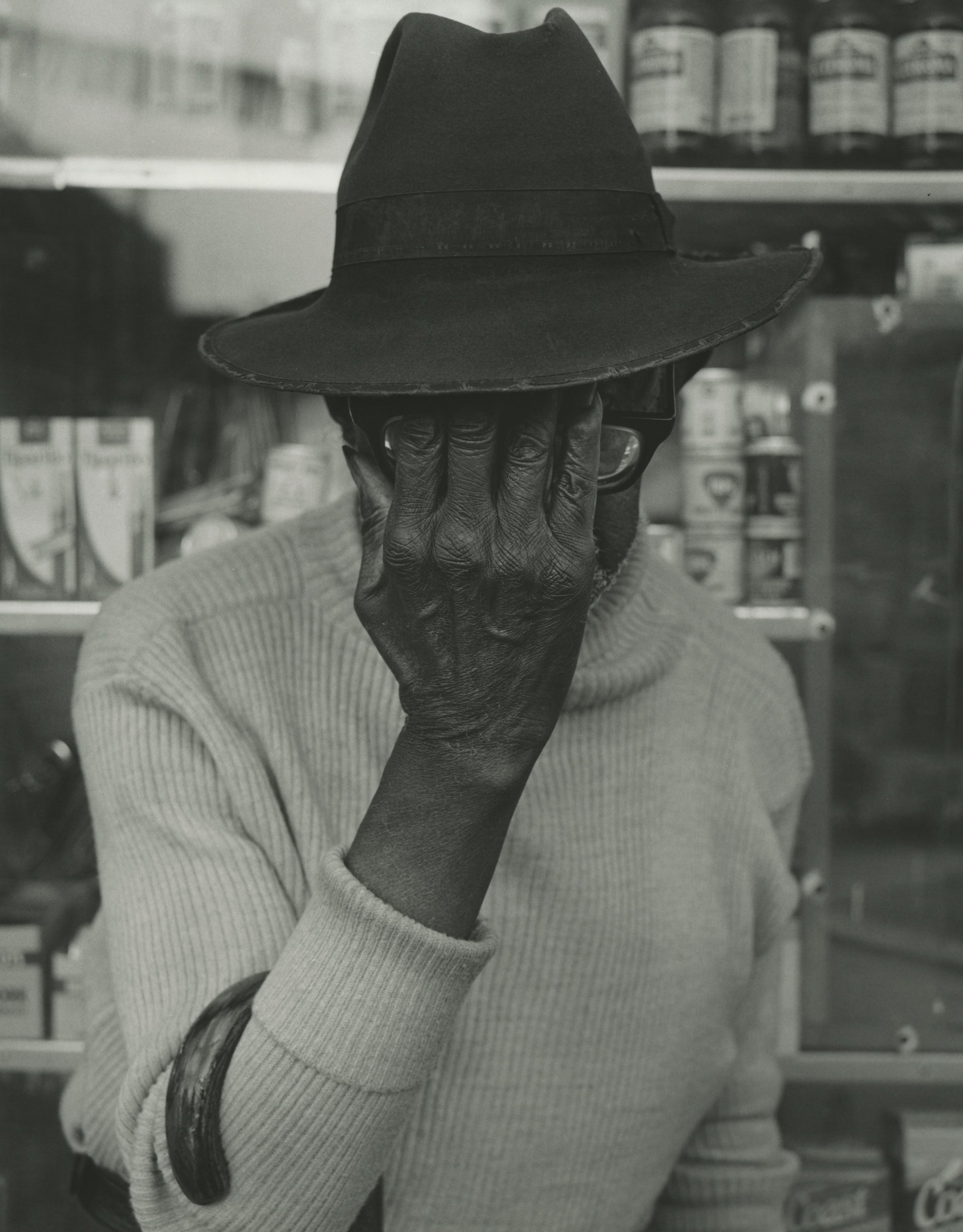

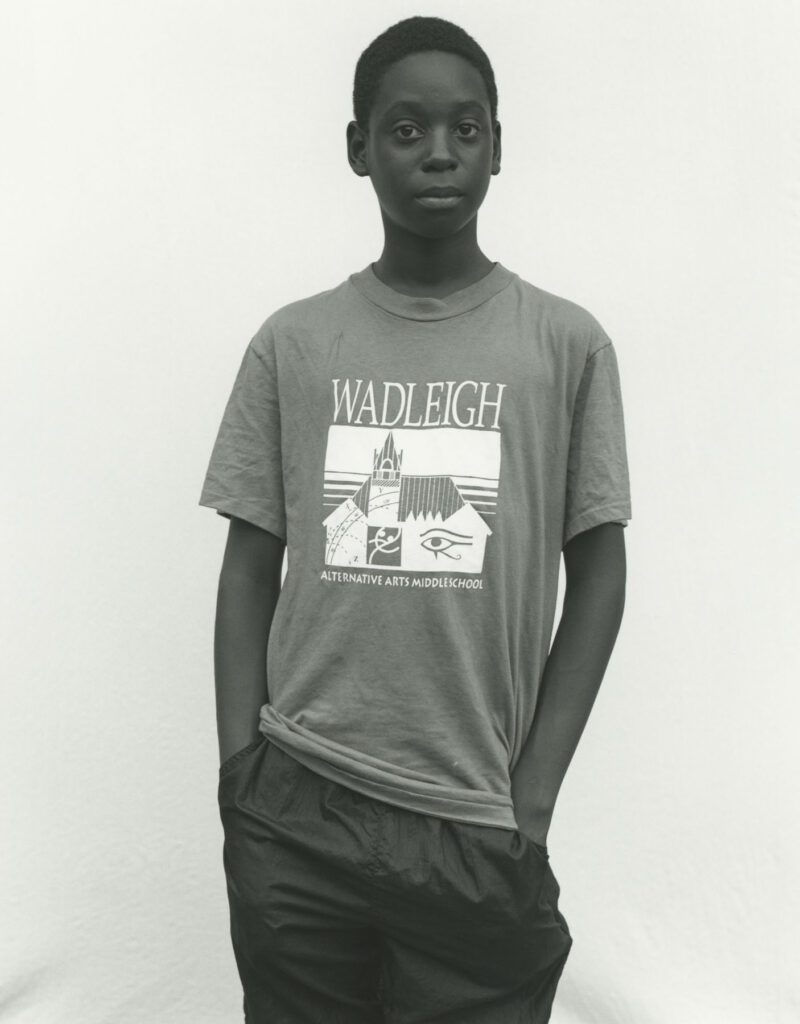

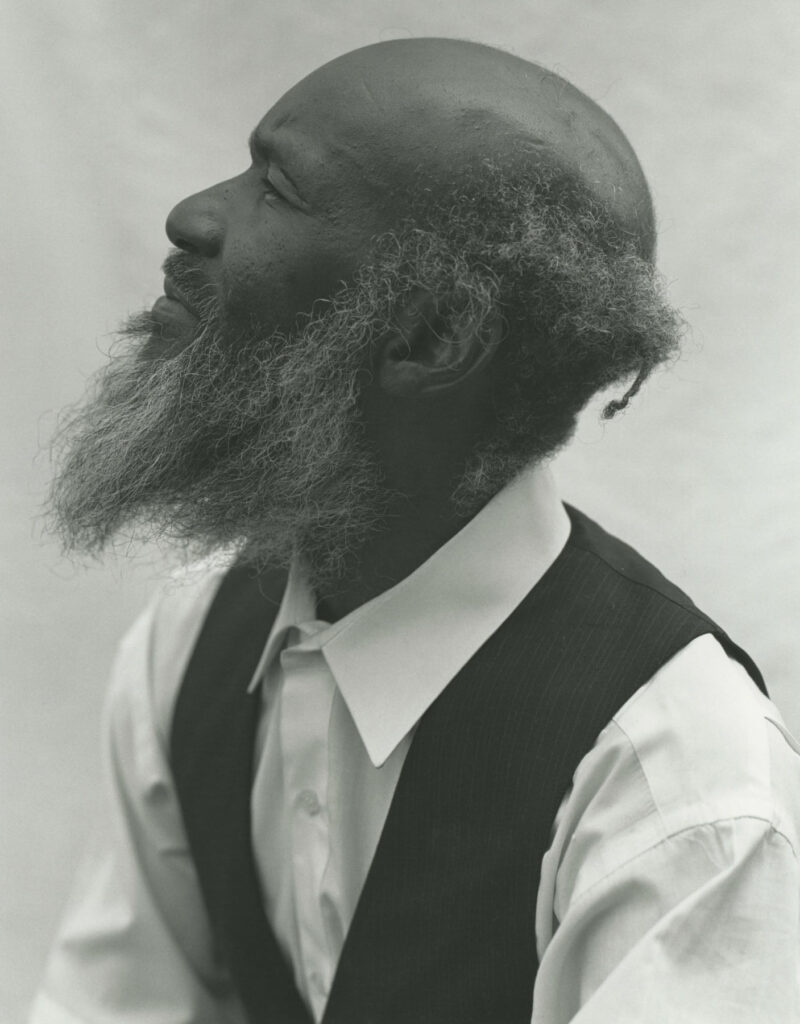

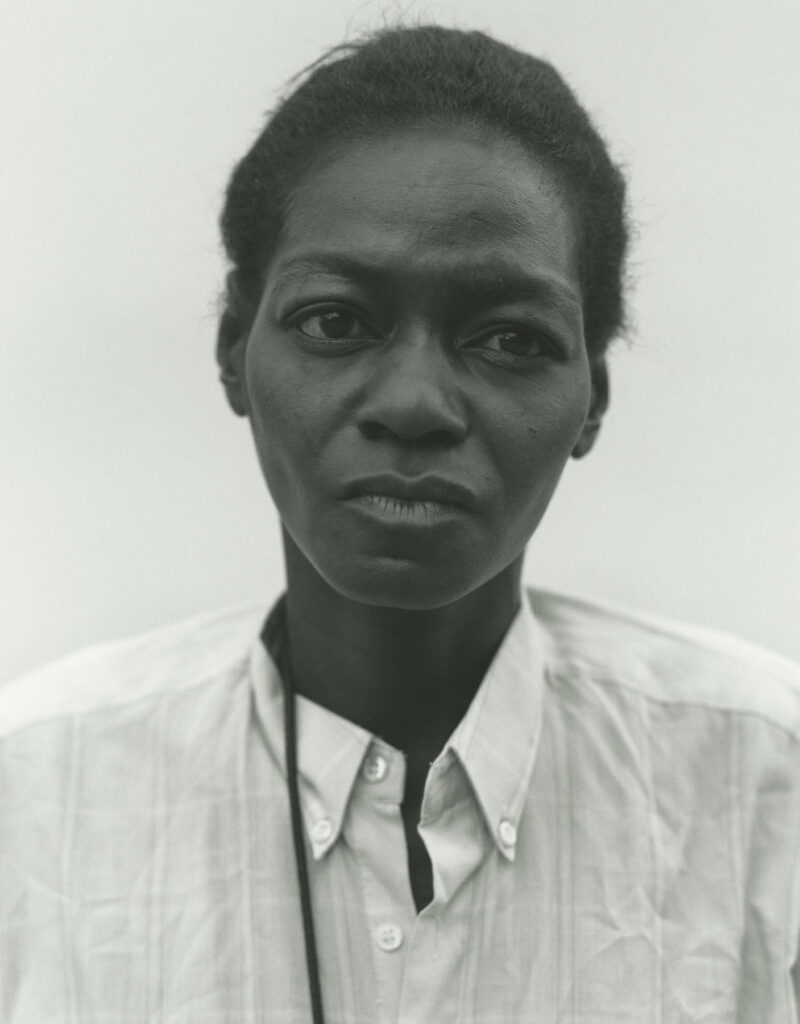

Photography · JACK JOHNSTONE

Creative Direction · NIMA HABIBZADEH and JADE REMOVILLE

Fashion · JAY HINES

Fashion Assistant · SERGIO PEDRO

Grooming · ELAINE LINSKEY

Manicurist · JULIA BABBAGE

Interview · ELLIE BROWN

Special Thanks to · Toast Press

Designers

- Jumper OFF- WHITE

- Suit and Shoes GUCCI Shirt TOM FORD

- Suit and Shoes GUCCI Shirt TOM FORD

- Jumper OFF- WHITE

- Jumper OFF- WHITE

- Top and Trousers HERON PRESTON Shirt and Shoes OFF-WHITE

- Vest KHOZA LONDON Belt OUR LEGACY Trousers SAINT LAURENT Shoes COMMON PROJECTS

- Coat, Trousers and Shoes PRADA Shirt OUR LEGACY

- Coat, Trousers and Shoes PRADA Shirt OUR LEGACY

- Top and Trousers HERON PRESTON Shirt and Shoes OFF-WHITE

- Suit BURBERRY Shirt TOM FORD Shoes DRIES VAN NOTEN