NR: Another image that stands out in the series is the one of prisoners; how does it fit into the series?

JAW: There are several pictures in the series – along with the one I just described that seem akin. For example, the hunting dogs chained to barrels and the parking lot with an older car and a building displaying a sign illustrated by cartoon description of dynamite exploding. There is something that feels comical, but, also telling. Both pictures are funny in their ways, but the underbelly of each is cold and covertly oppressive. There is something almost whimsical about the hunting dog picture despite the visible constrictions and brutality of the short leashes and imaginings as to how they function in the our world. The dogs appear over and over again, and if you look closely, you discover tiny dogs in the background standing on the barrels or shed roofs or hidden partially behind trees. I can whistle really loud and mearly every dog is alert, at attention, and looking straight at me, even those furthest back in the image. In the world of this picture, one can imagine that if the dogs were to run at me in their excitement once their surprise wore off, they’d be yanked back by the chains attached to their necks. In the image you refer to there are a group of prisoners in single-file with a barge behind them. They were picking up trash along a Mississippi River highway following a recent flood when I stopped my car. The sky is blue and the air is clear. The prisoners appear tame and benign. The tall, tremendously large, white prison guard sporting a long white beard had just ordered the surprised prisoners to get back to work. He is carrying a taser stick.

NR: There is something cartoonish about these images, but also a darkness in them, a violence…

JAWs: That’s it! Yes, there is an undertow of violence in these pictures, and the cartoonish quality contributes to this violence. The cartoons reduce and cover the inherent abuse implied in the scenes depicted: the prisoners and prison guard, the bunny-masked figure seen through the convenience store window decorated with easter decals, the parking lot and dynamite sign, and in some ways even the boy with the pumpkin. At first, this kind of humor might seem at odds with the tone of other pictures we have discussed but viewed within the entire body of work I think they act to cut away, cut through or partially subtract from the edge of sentimentality I explore in other images. In the picture of the hunting dogs chained to barrels, you can make a game of searching for and counting the dogs, a kind of Where’s Waldo? It could be a child’s game, but violent associations are embedded or buried.

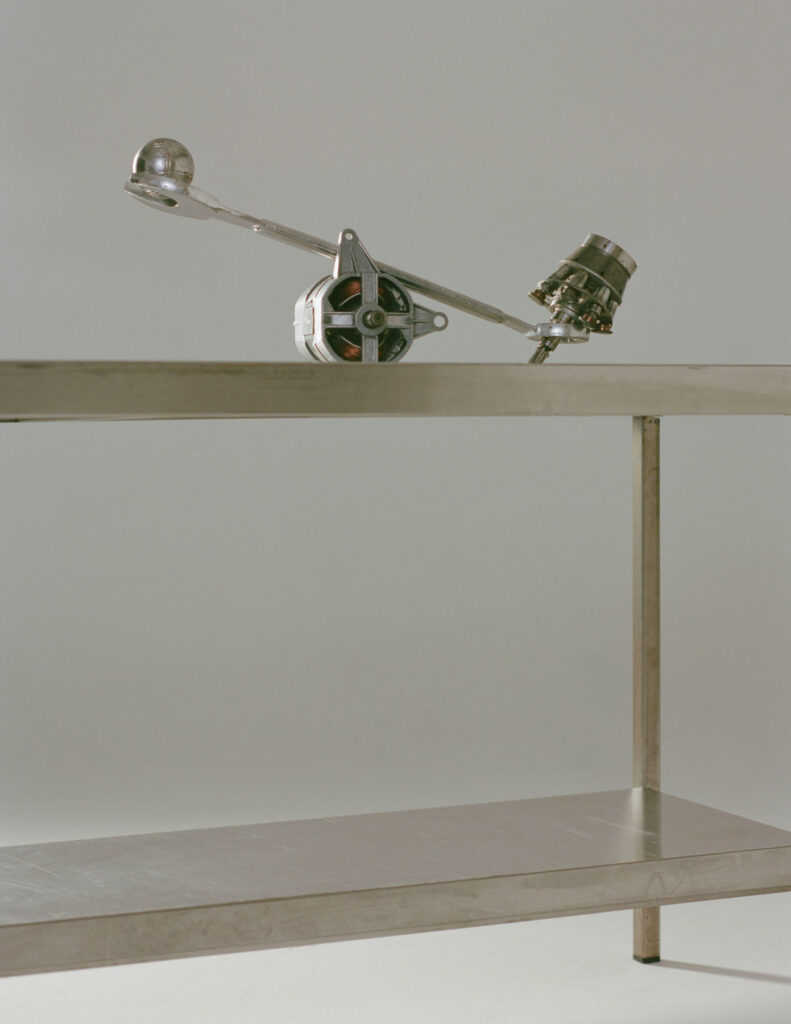

NR: I found it amusing that there are all these images of barren landscapes with heaps of scrap material and piles of cars, and, then, there’s also this picture of a window sign, which reads ‘top dollars paid for scrap gold and silver’.

JAW: I don’t know if I’d use that picture when I get around to publishing a book of this work. The image is illustrative, more so than other pictures throughout the body of work. My father was a relatively successful small business owner and what some might call an upstanding citizen, and as I said earlier, he ran a sheet metal fabrication factory. After he retired, and without the constant structure of a work-week, he was often at a loss as to what to do with himself. He retired early and drank more, just like nearly everyone in town. There was nothing much to do. As a way to socialize, he would sometimes hang out at pawn shops with other men. Perhaps this is one reason why this picture seemed vital to me for a while. As an image it illustrates something about the realities of class and economics in post-industrial towns of this size. In the end, I think it lacks the subtlety that I’m usually drawn to. I try to particularize and keep cultural information to a minimum to slow the pictures down, and so the viewer has to travel through the sequence of images in multiple ways. I like pictures to suggest uncertainty or rather carry multiple meanings that are often in contradiction to one another, and to do so all at once. I like doubling and tripling ambiguities, tensions, and constellations of associations through individual images, sequences of images and the intervening spaces between images. In DOG Town, I want to evoke meanings such as that which is overtly illustrated in the picture of the pawn shop, but to do so in slower, more nuanced and porous ways.