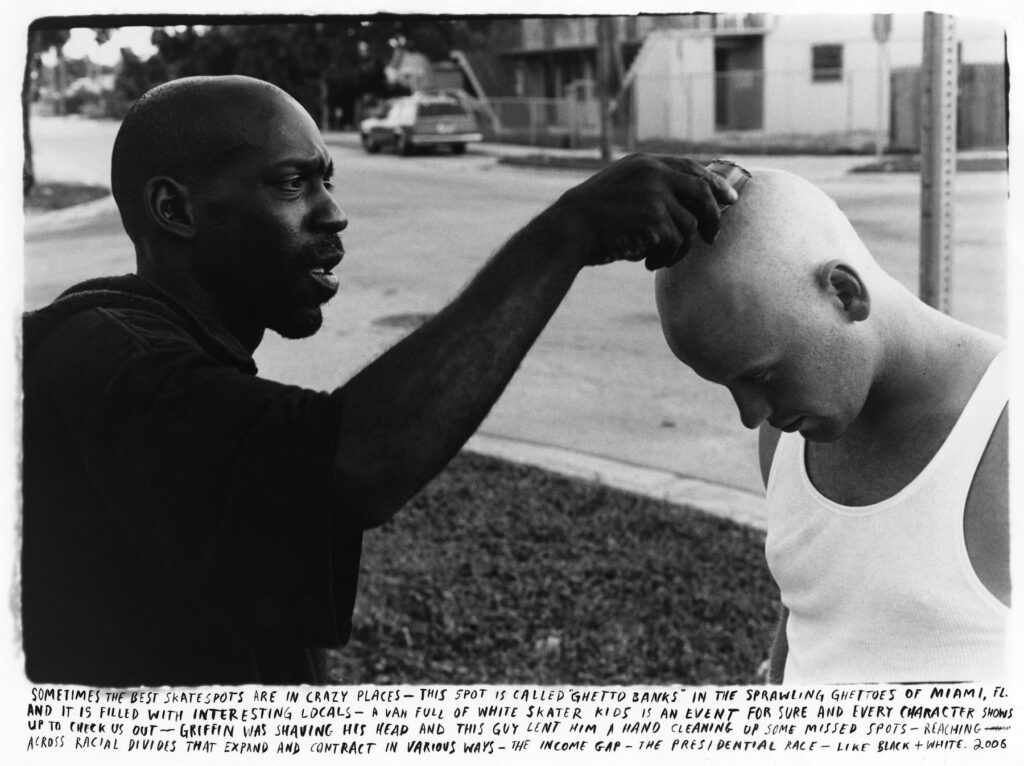

“The Bronx had been burnt, and you have a collection of youths’ who were trying to find their identity and their voice in, essentially, a city of no hope”

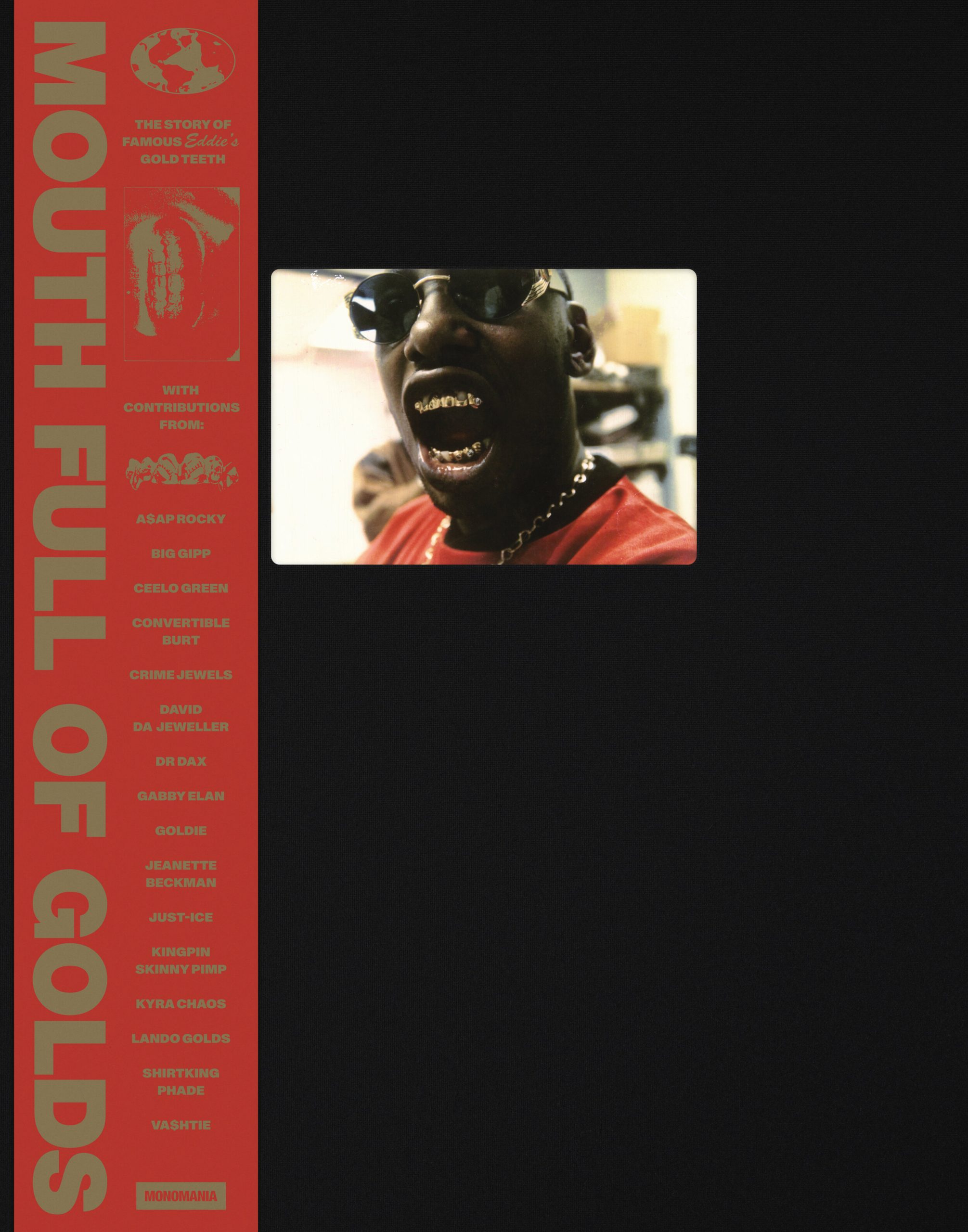

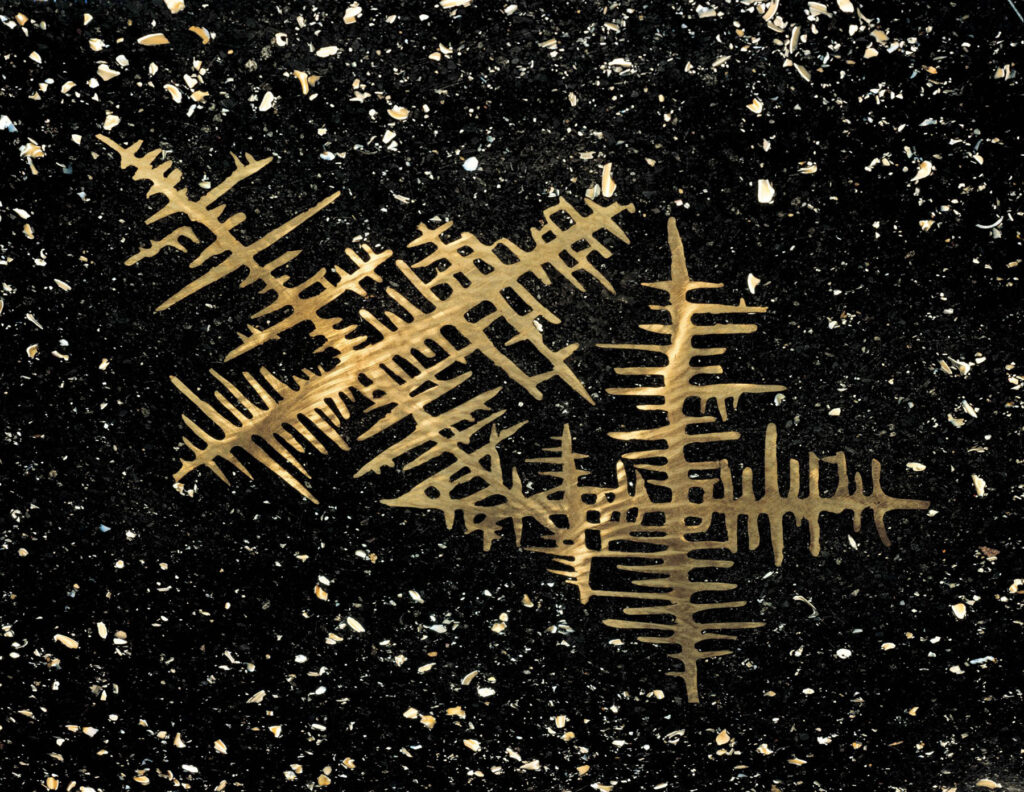

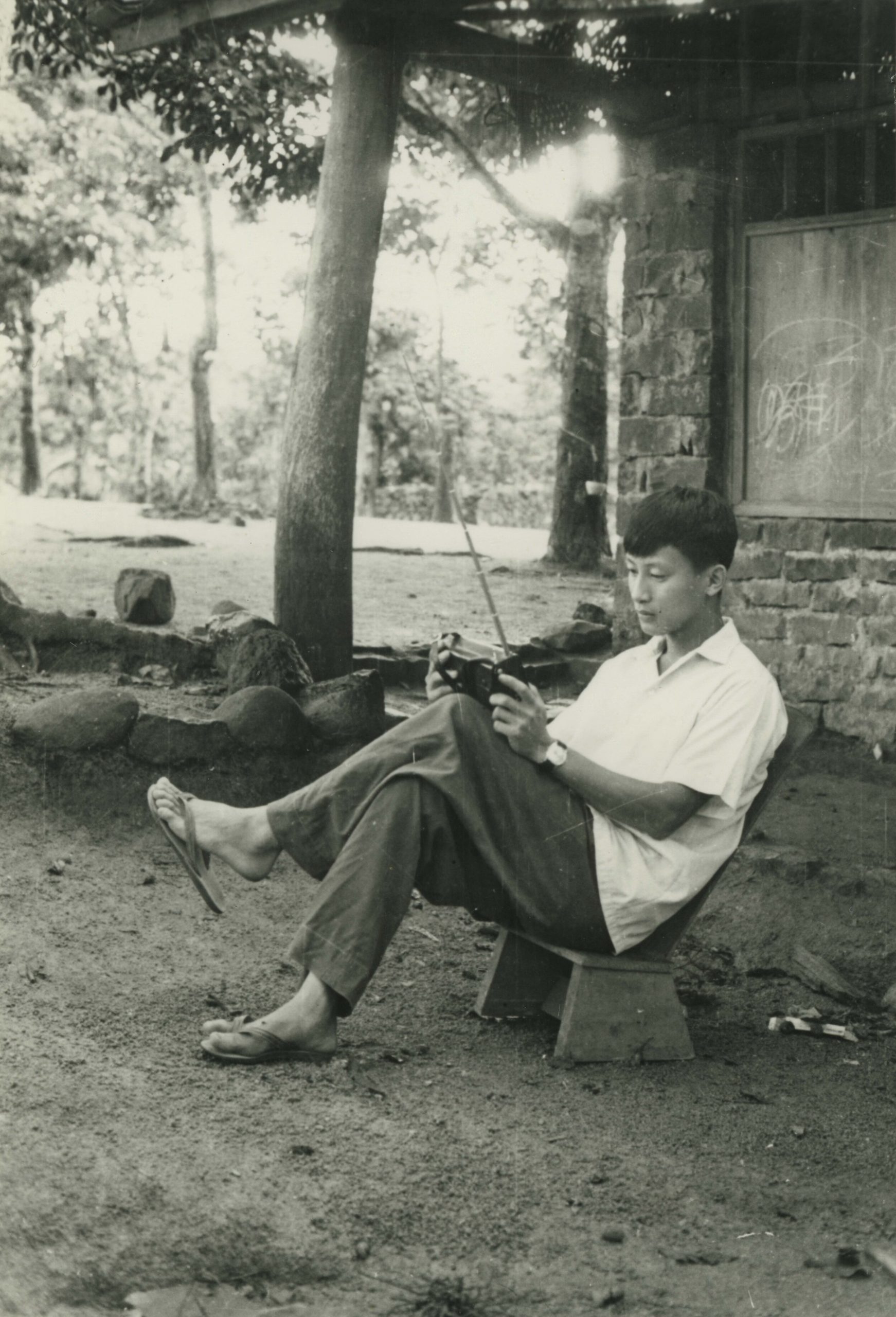

You would think that someone who invented some of the most iconic and instantly recognisable jewellery of the last few decades would be a household name by now, but Eddie Plein is only just getting the recognition he deserves for inventing grills. Born in Suriname, Plein moved to New York with the rest of his family in his early teens. He was an aspiring soccer player, but watching his father hustle to provide for his family in a new country Plein knew he was never destined for a traditional nine to five. It was the eighties and in Brooklyn Plein was surrounded by the budding hip hop scene.

Then, on a visit back to Suriname, he cracks his tooth and the dentist offers him a gold crown. Gold is one of Suriname’s biggest exports, which makes it a cheaper alternative for dentistry. However, Plein didn’t want to commit to a permanent gold crown and that’s when his ‘lightbulb moment’ happened. Back in New York he dropped out of college, put his dreams of being a soccer player on hold and went to dentistry school long enough to learn how to wax up crowns before starting his own business. He pioneered the technique of creating pull out crowns, which we know today as grills. The rest is history, and what a star-studded history that is. Plein, it seems, has made ‘teeth’ for all the big names. NR Magazine was joined in conversation with Lyle Lindgreen co-author of Mouth Full Of Golds which explores Plein’s forgotten story and the rise of grills.

How did the collaboration between you and Plein for Mouth Full of Gold come about? Is there a story behind it?

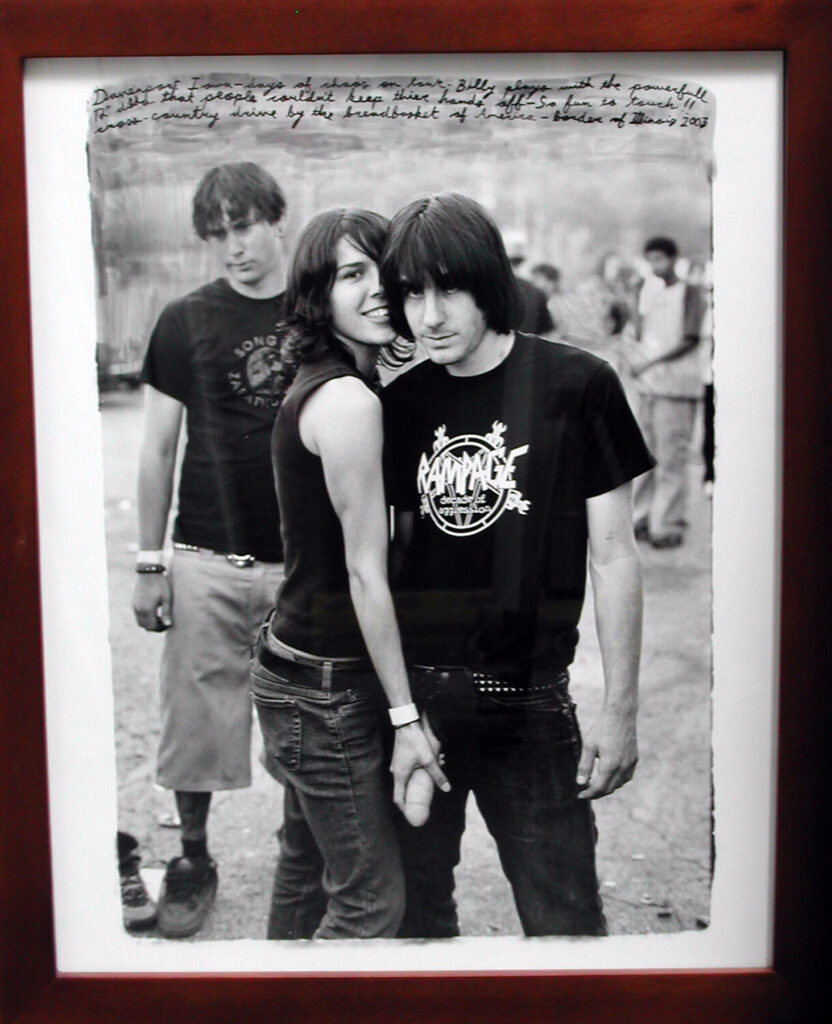

So I’ve been obsessed with grills since I was a very small kid. I had Gravediggaz album which had The RZA on the cover with a set of vampire fangs. I must have been like seven or eight when I saw that cover. I was just really enamoured by that image and always wanted a set. Also, I remember seeing images of Goldie in different print magazines during that kind of drum and bass era in the late nineties. So I’ve always really been drawn to the concept of gold teeth and then the opportunity came up to shoot some films with Goldie for an art exhibition he was doing.

So I shot these films and asked him loads of geeky questions and we just hit it off and ended up doing more projects together. We were going to New York to shoot a graffiti film and I wanted to get a set of teeth made while we were there ‘cos there wasn’t really anyone in the UK doing it. Goldie casually mentions that he used to live with the guy whose brother invented grills. So me being quite inquisitive, I was like “No one invented it”, and he was like “Nah, I used to live with the guy in Miami, his brother was like an OG New Yorker.” Goldie is very immediate so he was like “I’m gonna call Lando now in Miami, get Eddie’s number and when we go to New York we’re gonna go meet up with him.”

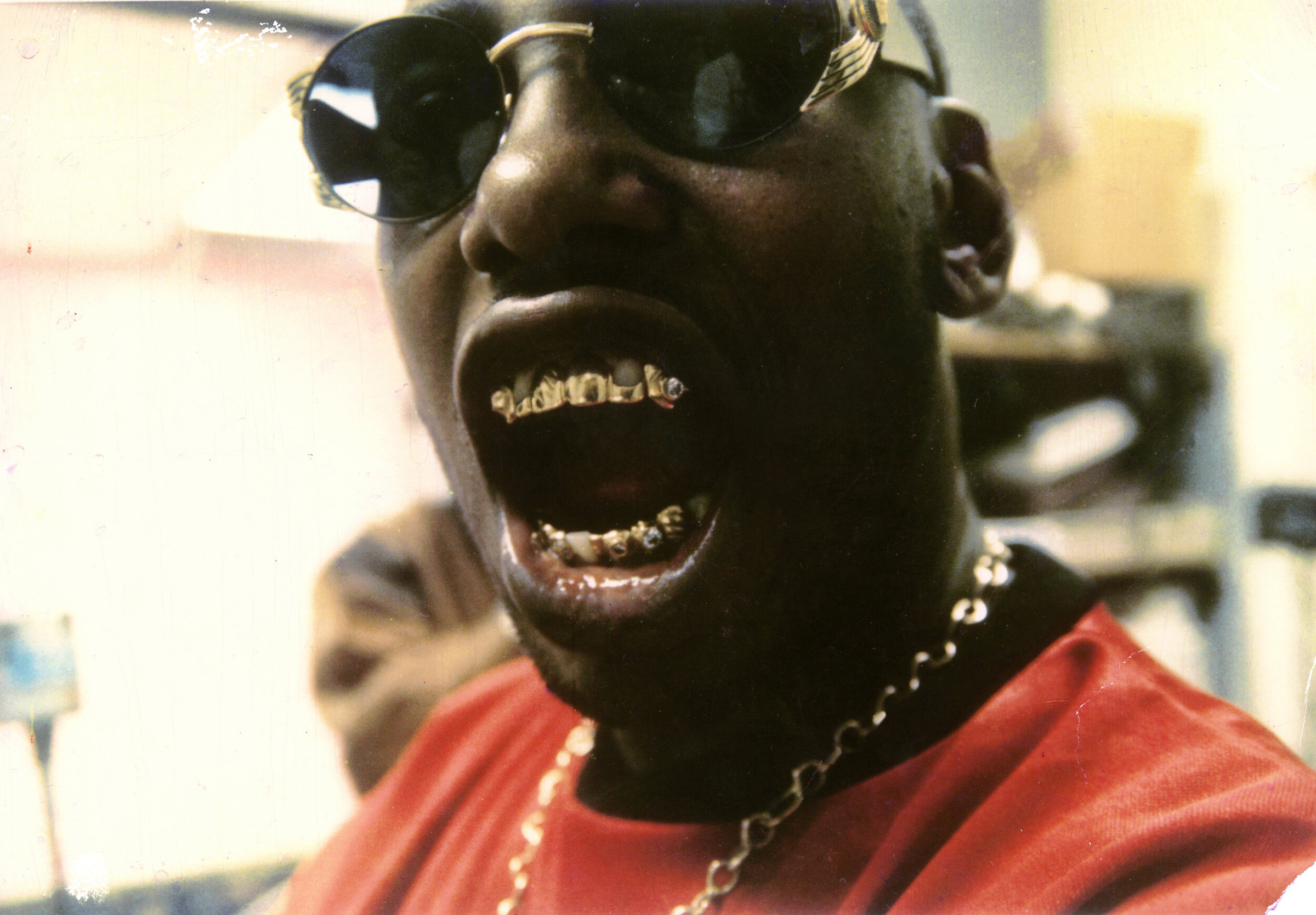

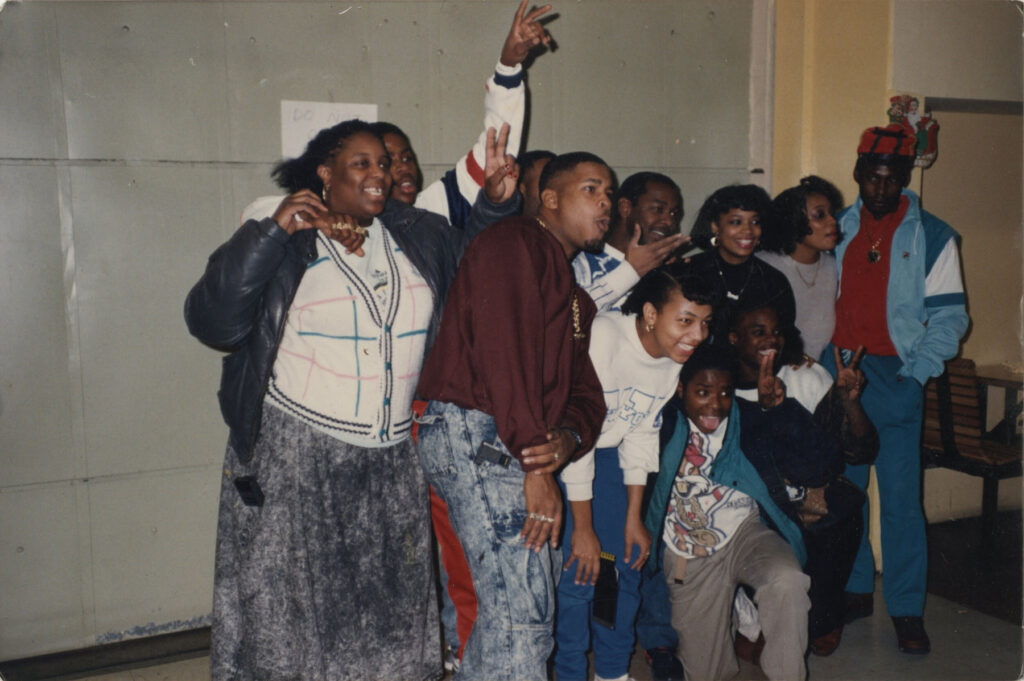

We go to meet Eddie at the Coliseum which was the original spot where he kicked off his career. We turn up there and we’re waiting and waiting and he doesn’t show up. Then this big fight kicks off on the block outside the Coliseum and we are like there with all this camera kit. So as the fight kinda calms down, the questions start coming in about “What, did you guys film anything”. We were trying to say “No, we’re just waiting for someone”. And then Eddie casually rolls up, pushes through the crowd, to say “what’s up” to Goldie. Then someone from the group is like “Who are you?” and he says “I’m famous Eddie. Gold caps, the Coliseum.”

“Then it’s like a scene from the godfather, and people started coming out of their stalls like welcoming Eddie back to the block.”

So we end up walking away from the Coliseum. He’s shaking hands with people who are like “Eyy, I haven’t seen you for twenty years”, “Eddie, you ‘da man”. Then we end up jumping in this cab and going to Eddie’s house in Brooklyn. We go to the basement of his family home to film and do an interview with him. And it’s the very basement where the whole story started. So Eddie very casually starts telling us about, “You know I made these teeth for Nas, Ludacris, CeeLo”, and the list goes on and on. We’re filming as he tells his story for the first time in a very humble way. And,

“I was just thinking he’s either one of the most amazing fashion icons you’ve never heard of or its straight cap. ‘Cos it was just unbelievable.”

So we shoot a piece for Eddie, and it was originally going to be a five-minute film. However, then I ended up going out to Miami to meet his brother Lando, who was Goldie’s roommate. It was from there that the project just got bigger and bigger and snowballed into this story that spans like thirty-plus years. Eddie and his family just made teeth for everyone, like teenage Jay-Z through to André 3000. Eddie’s reach across the east coast of America is so deep.

Do you think Plein’s work helped shaped both regular peoples creative identity through self-expression, and creative identity in the music/rap scene in Queens, Harlem and Brooklyn, in the ’80s?

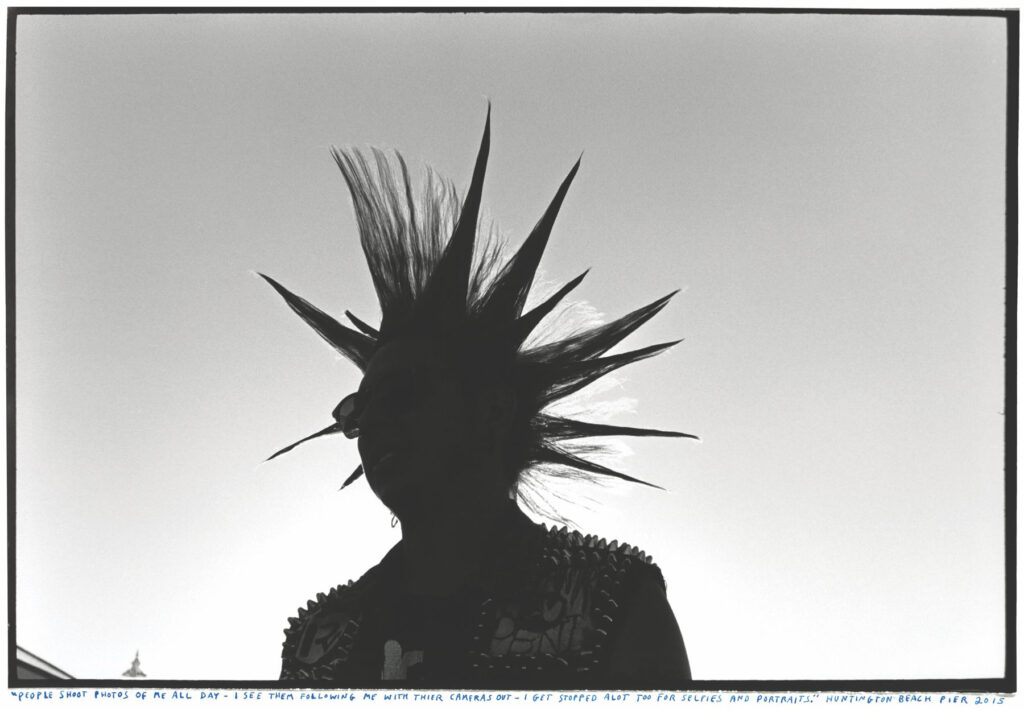

A hundred per cent. So at that point in time, the youth of New York was going through times of great austerity. New York had been bankrupt, The Bronx had been burnt, and you have a collection of youths’ who were trying to find their identity and their voice in, essentially, a city of no hope. So from that, graffiti spawned with people wanting to make their mark. It’s the same with hip hop and just jewellery in general, with the concept of jewellery allowing you to pick something personal, to your taste. Through this period of great austerity, you have finance coming to the city in the form of crack cocaine. Then the finance surrounding hip hop that kind of follows the crack era. So through coming of age, and coming out of austerity, people will always use their fashion and their jewellery as a way to express themselves.

The book’s blurb describes Plein as ‘one of the greatest fashion icons you’ve never heard of’. Do you think it’s a common issue for black creatives and pioneers to be overlooked whilst their work is stolen and appropriated?

Sadly yes, I do. And I think that an element of it is to do with just how fashion is perceived in certain cultures. Obviously, the big fashion houses have the money and resources to preserve their legacy. You have fashion houses that have hundreds of years of history. And it’s all documented and archived and they lean into the history to make themselves prestigious.

With a lot of people like Eddie and Dapper Dan, for example, their work is often overlooked. In that era, there was a lot of pressure on them with what they were trying to do, and how they were trying to build their legacy. Certainly, with Eddie, it became a very competitive game and it got to a point where Eddie got kind of tired of the process. You wanna move on to something else, and you maybe don’t have the resources. The book is a big part of that, it shows his legacy kinda just in a basement, discarded. That’s why we did this project, to preserve it.

“Eddie was definitely a pillar in that world, by allowing people to customise and show their personalities. Eddie’s whole idea of making grills really comes from having quite an outside perspective.”

He wasn’t part of the dope game and he wasn’t necessarily in the hip hop community at that point, as he was really focused on being a soccer player. However, he was in Brooklyn and was watching guys on the block, seeing how the jewellery developed from subtle chains into these massive rope pieces and four-finger rings. So through watching how people are expressing themselves it allowed him to have his lightbulb moment. He cracked his tooth when he went back to Suriname and all these pieces suddenly came together in his head. Like “I’ve seen how fashion is on the block, I’ve seen this advert for dental school when I’m riding the subway”. He’s thinking “You know I could make these caps and sell them to people” and then with that he’s able to facilitate what people want. So, he definitely helped shape people’s creative identity. I think just from people really pushing fashion and wanting to stand out and it being very competitive, from what I’ve heard it was very competitive in fashion in that era, it allowed Eddie to kind of just push what he was doing. Just create whatever he wanted.

The book’s blurb describes Plein as ‘one of the greatest fashion icons you’ve never heard of’. Do you think it’s a common issue for black creatives and pioneers to be overlooked whilst their work is stolen and appropriated?

Sadly yes, I do. And I think that an element of it is to do with just how fashion is perceived in certain cultures. Obviously, the big fashion houses have the money and resources to preserve their legacy. You have fashion houses that have hundreds of years of history. And it’s all documented and archived and they lean into the history to make themselves prestigious.

With a lot of people like Eddie and Dapper Dan, for example, their work is often overlooked. In that era, there was a lot of pressure on them with what they were trying to do, and how they were trying to build their legacy. Certainly, with Eddie, it became a very competitive game and it got to a point where Eddie got kind of tired of the process. You wanna move on to something else, and you maybe don’t have the resources. The book is a big part of that, it shows his legacy kinda just in a basement, discarded. That’s why we did this project, to preserve it.

And do you think that books like Mouth Full of Gold will help solidify those legacies?

Yeah after that first encounter with Eddie, this is maybe six or seven years ago, I went away and started looking into Eddie but there was nothing online about him, it was completely tumbleweeds on Google. As we have developed the project, more stuff is starting to go online about him. I feel like what happened with Eddie is he sort of disappeared into the shadows just as the wave of the internet really broke. Because he didn’t transport his legacy online, it can feel like it doesn’t exist.

So I feel what the book does is solidifies that history, with all the evidence and the archival images, in a physical place. Obviously, there are things going online as well, but if twenty years down the line of certain sections of the internet don’t exist anymore or we move onto a new form of communicating, at least it’s there documented in print. Making sure it’s told in a really heavily researched format, so the next generation that will uncover the culture will have that information.

What’s your opinion on the issue of cultural appropriation with many white celebrities wearing grills, such as the Kardashians, Harry Styles and Madonna to name a few?

So over the last decade, grills have transcended to high fashion. They are now viewed as an accessory, in the same way that you might look at a prestige wristwatch, but their placement is just in the mouth. What they represent is so synonymous with that culture and history that you shouldn’t be able to view them on a celebrity and not be able to identify immediately where that style originates from. There’s always gonna be that thing where people look at grills and immediately identify them with hip hop.

I feel like they’ve gone to a high fashion space where people are just using them to accessorise. Now, whether a celebrity really understands the culture is another question. I personally look at their motivations of why they wear them, the designs they pick and the longevity of wearing them to kinda understand why they are rocking grills. I do think a lot of celebrities are disingenuous with it. I think they use grills as a press moment for a music video or a carpet walk. As soon as you see a set that they are wearing, you never see it again. So,

“I think a lot of the motivations behind celebrities wearing them, comes from quite a disposable place.”

I think that mainstream attraction has its positives for the jewellers. When someone sees a set of grills on a celebrity like Kim Kardashian, it’s gonna lead to interest for jewellers and they need to have an economy that stimulates their business. So it’s a positive in the sense that it allows jewellers to have an audience which helps them involve the art form. But their bread and butter clientele doesn’t come from that space, and it comes from a more authentic place. It will always exist like in culture in a very deep rooted place as it has so much history behind it. It often peaks in the mainstream and then it kind of rides a wave and disappears, but it has always had its roots in black culture in a very authentic way.

With many things that are culturally appropriated, it can be almost impossible to pin down a sole original creator, but obviously, grills are Plein’s invention, so I’d be interested to know what his opinion was on people, who aren’t black or from that culture, wearing grills is?

I mean I wouldn’t want to answer on Eddie’s behalf, but we’ve had conversations about it. From a business point of view if you came down to Eddie’s shop and the money was alright he’d make the teeth for you. Every shop Eddie’s had he always created a vibe that was very much linked to his personality. You’d go in there and he’s got crazy pictures of soccer players on the walls, or traditional Surinamese woodwork, or pictures of grills he’s taken and just like a vibe. The communities Eddie based his shops in, that would stimulate his business, have always been predominantly black communities. So at those points in time when Eddie was making grills, it was intrinsically linked to hip hop and black culture. But I think in terms of Eddie’s clientele he will make teeth for anyone. Eddie is more interested, and we have had a few conversations about this, in what you want. There are certain things that he won’t design, like if he’s just not feeling the vibe or the motivations that are there. I remember once he was telling me a story about André 3000 when he wanted a copper set of teeth. Eddie was quite against making these teeth for André 3000. He didn’t want him out there wearing a copper set that he made which looked cheap.

What was the most interesting thing you discovered while working on Mouth Full Of Gold with Plein?

Two things. First was that Eddie made some teeth for Allan Iverson at the height of his basketball career. He came to the store in Atlanta to get a set of teeth made. So that in itself was interesting. But then Eddie alluded to the fact that his wife used to play bingo with Iverson’s mum when they left New York and moved to Virginia. Also that Eddie’s daughters went to the same high school as Iverson. So Eddie was telling this anecdote of how Iverson is like a god at this point and he comes to the store and Eddie’s like “Oh yeah my wife used to do bingo with your mum and my kids went to your high school” and suddenly everyone knew all the same people and everyone’s business. I’ve never seen any pics of Iverson wearing his grills, he had rose gold grills before anyone was really into rose gold so that was quite interesting.

The second thing was the most interesting, Eddie told me that the majority of the images in the Nelly – Grillz music video with Paul Wall, Ali and Gipp are all from Eddie’s shop in Atlanta. This was like at the end of his big run in Atlanta before it kind of changed hands to a Houston take over. So Eddie told me they’d come and asked to use all the images from his store. It was a song about grills but Eddie never cameoed and wasn’t in the video. I’ve been through it frame by frame and there’s a picture, which is in the book, of Eddie and Ludacris that you can see just tucked away in the corner. I thought that was quite interesting and also quite sad to uncover that.

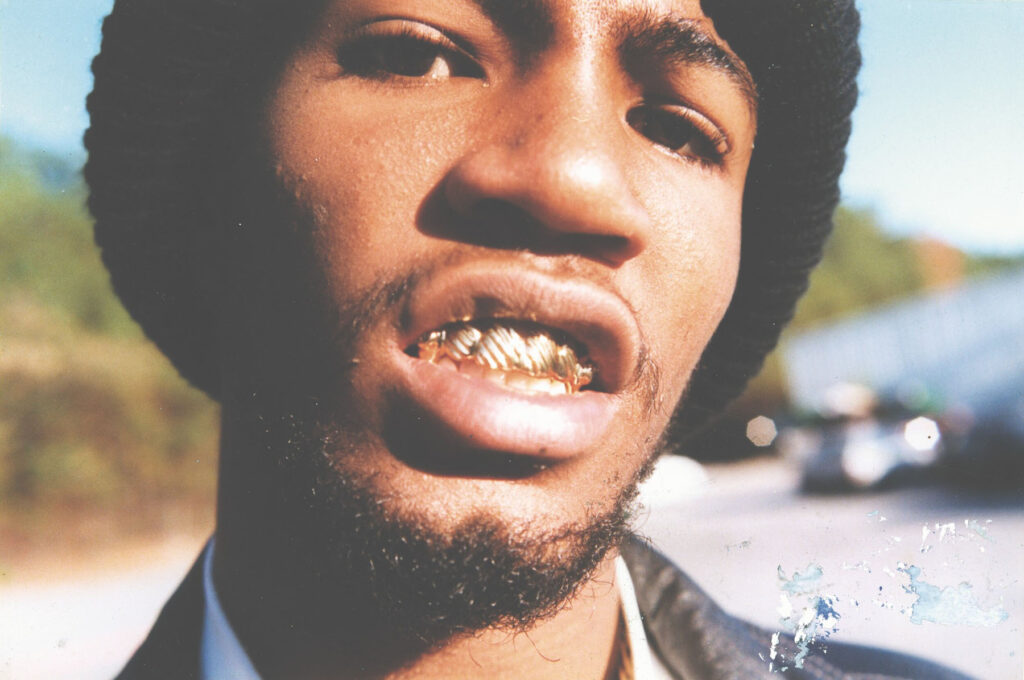

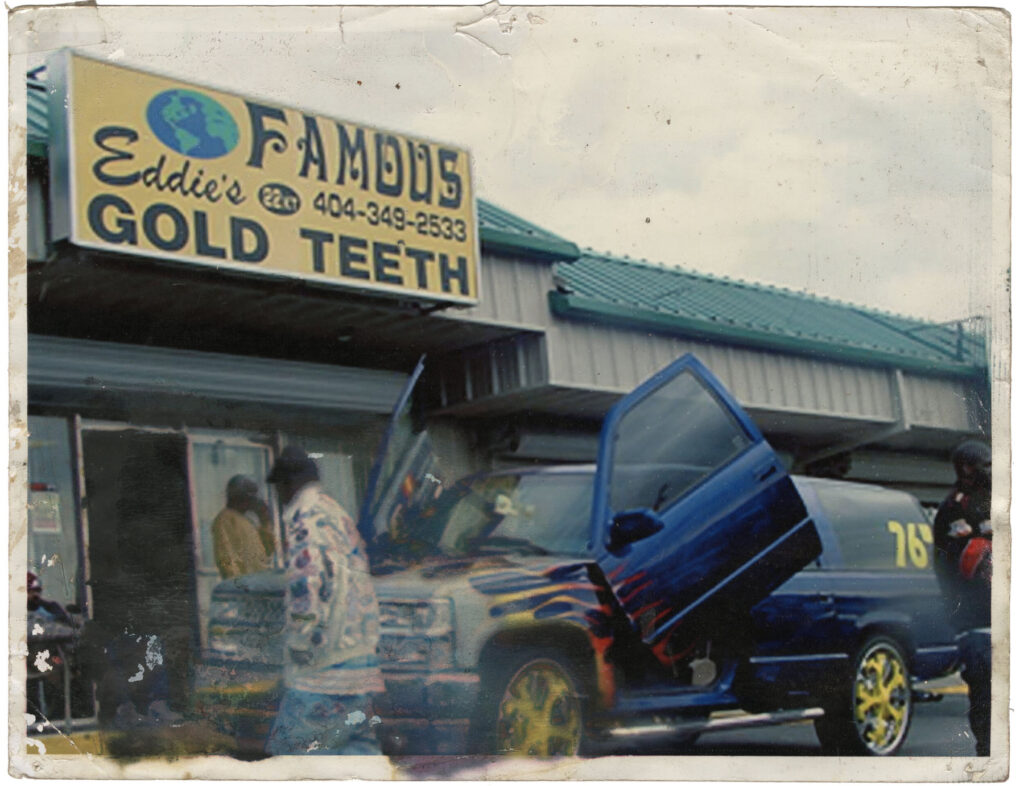

Plein describes Atlanta as a resurgence of New York but with a different vibe. Did that difference have any influence on his work at the time?

Yeah in New York he would make a lot of single sets where he would very often put two or three teeth together. People might have eight caps at one time but very often it was like two’s and three’s. So really,

“Flavour Flav was one of the first customers he had where it was like six teeth put together. It was becoming less caps and more grills in New York.”

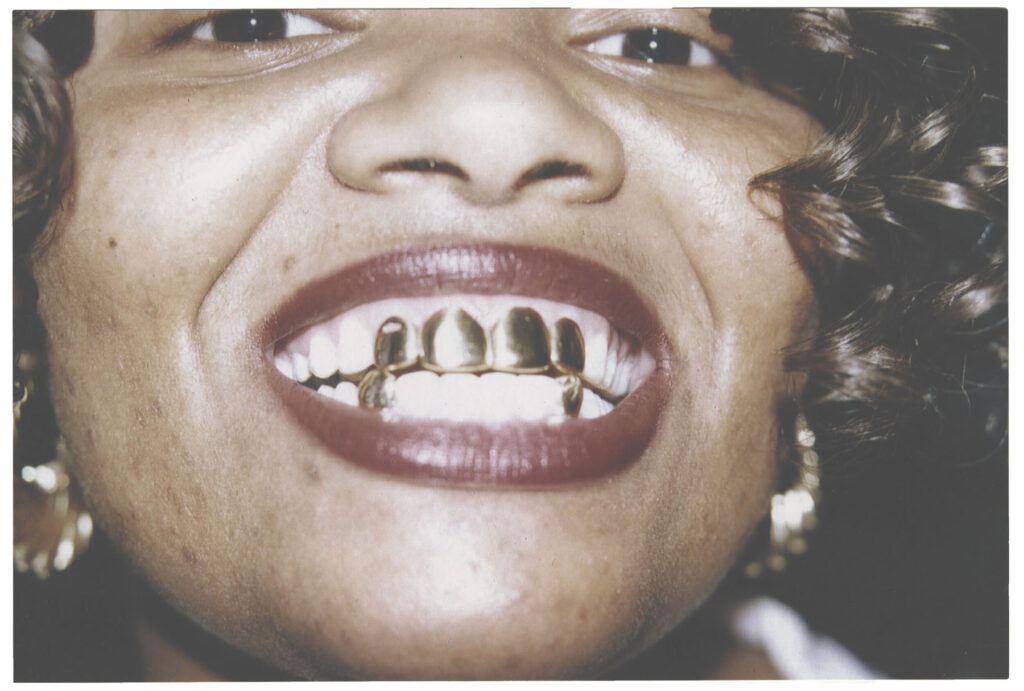

But when Eddie goes to Atlanta he starts making more grills with six teeth and eight teeth put together. So it ushers in this era in his creative career where it’s about making bigger put together pieces. This allows him to start experimenting with diamonds. Before customers might say “One tooth, cover it in diamonds. The next tooth I want you to put a Benz symbol.” However then you have Goodie Mob come in, with CeeLo and Big Gipp in particular, and they really pushed him to try different things. So you have CeeLo asking Eddie to make him six teeth put together that are all like classic New York nugget-style, or Big Gipp pushing Eddie to make platinum grills which they hadn’t really done before and wasn’t on his radar.

It was different from city to city. Eddie tried to strategically place his brothers in different states so that they could replicate the success they were having in New York. So when his brother Lando goes to Miami, where he meets Goldie, he’s going into a culture where everyone just has permanent gold teeth. They would go to the dentist and get their teeth filed down and have just permanent crowns in. It was culturally evolved from street culture, so a lot of pimps and hustlers would have one or two permanent crowns. Also, the dope boys were getting their shot at the top so they were trying to evolve it and be like “Nah I’ve got like eight on the top and eight on the bottom”.

Lando went into that culture and was like “I’m trying to make these pull out teeth”, and everyone was just laughing at him thinking “Why do you want your teeth to come out if you’re really street? You should commit to them so they are in there permanently.” So Lando has to figure out how to evolve in Miami and he starts making grills that could go over permanent teeth, grills over grills.

Plein suffered from people copying and undercutting his work, do you think his so-called downfall was inevitable or could it have been prevented to some extent?

Yeah, I’ve spoken to Eddie quite a lot about this, so in New York, his downfall was that in the booth in the Coliseum he housed the whole process in that booth. It essentially put the whole production on display so you could see how it was done. The issue with that was other jewellers could come by and see how he did the whole process. Then you are faced with all the copycat jewellers who understand how to do the process but without necessarily having spent the same amount of time as Eddie sitting in the basement like learning how to wax up perfect teeth. So also he was undercut by jewellers who make an inferior product and Eddie prided himself on the quality of his teeth. So those mistakes in New York he definitely took them away with him and in Atlanta, the idea is that he kind of had a shop front where people could come and kick it. Play pool, order their teeth and hang out drinking. It became like a social club and then a building to the right housed the lab, so you have a team there that’s away from the openness of the shop.

“Really the way to not fall off is to just keep evolving and I think Eddie as he moves into the millennium he’s on top of the world and he’s king of the game.”

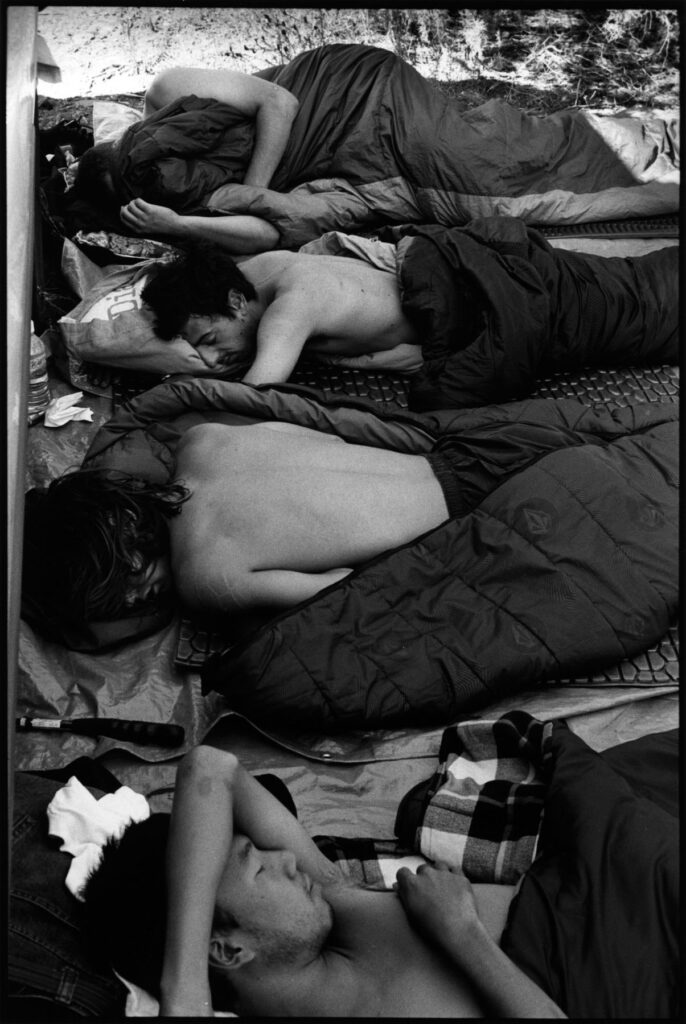

He had this element of being complacent and thinking “you know what like fuck the internet I’m not into the internet like I don’t need to do that people can come and find me cos I’m the best”. But then other people with a bigger platform, like Paul Wall, come along and the phone starts ringing less. I think for Eddie, and he talks about it in the book as well, there’s kinda like a denial of falling off. He just got outsmarted and out-hustled by someone who came in and had that massive platform. You gotta have that fire to keep evolving but, around the sort of mid 2000s, Eddie’s already twenty years in the game. That’s a long time to keep reinventing yourself. After the Atlanta store closed Eddie’s dad in New York got sick so Eddie went back to care for him for the best part of a decade. He kinda took himself out of the game to reevaluate what was important for him, you know his dad being his idol, so he wanted to go home and play his part there.

Do you think that the use of gold grills as a form of self-expression amongst African American and Latin American communities can be seen as a form of activism against colonisation which stole natural resources such as gold from Africa and Latin America?

Yes I do. I think gold crowns themselves date back to like to the late 1700s. As I researched the book I found that diaspora communities will often take what is essentially a crude form of dentistry, not getting a porcelain crown but a gold one because it’s often cheaper. They will take it and make it an investment piece for a rainy day. There’s a school of thought of protecting the wealth by putting it into your teeth.

I made a film about this true story in Lando’s shop where some guys in Miami had been on a bit of a crime spree. They knew that they were going to go away for a long time so they went to Lando and got all these permanent golds put in. The police tried to understand what was the point of it when they were about to get banged up and go away for time. What Lando brought up was “Yeah you’re gonna go away for a long time, but you are gonna sit in a cell knowing that you have all this gold and diamonds in your mouth and when you come out you’ll have enough capital to get started again.”

Also, people have taken this often cheaper form of dentistry and revitalised it in a way where it’s flamboyant. Pre grills you see it in West Indian communities, people still have one or two teeth here but it still looks fly and it still looks affluent. It’s definitely a thing where people do take it and use it in a way that’s a reaction to recourses that have been taken.

“Through colonisation people are taking those resources and when recourses are taken away from you in abundance, even if it’s like a small way of having them and being able to show them off it’s still a very defiant act.”

Do you think that grills will retain their popularity going forward with music artists such as A$AP Rocky and Rhianna continuing to keep them in the spotlight? What are some ways you think they might evolve in the future?

I think in terms of its popularity it’s very cyclical. New generations take an interest and that really pushes jewellers to innovate the teeth to crazy levels. We are seeing it now with a lot of 3D printing, enamel painting, certain stones which are being set like opals which you haven’t really seen before. At the moment one thing that’s happening is this wave of perfect veneer teeth that’s becoming very popular. You go get your teeth filled down like shark teeth and you get the veneers put over them like Tipp-ex white teeth.

But then Rocky has got some amazing tiny diamonds that are actually drilled into his teeth in the enamel and I think that’s something that could take off. I think Drake has a nice diamond in the front of his perfect teeth. Gucci Mane had all his veneers done and then he went and got amazing single diamonds put into those veneers. It could be that it becomes an amalgamation of the two cultures of perfect veneers and a sort of variation of grills.

I think they always will continue away from the mainstream. Gold teeth are consistently present in cultures and communities away from the hype. Miami and New Orleans have such a deep history of permanent golds such an ingrained part of their culture I don’t think it’s gonna leave. I think that shows where you stand with the culture. Like are you gonna continue to wear your grills when it cools off? Or are they gonna go in the drawer?