Like water through a closed fist, success seeps before permeating, so often we are only left with a feeling. Uncurling his wet fingers to peer down at the traces left to puddle in the creases of his fissured palms, Jonas Åkerlund yields a single flick of the wrist, scattering droplets skyward before running it through the tresses of his long, greased, black hair. It’s hot, midday in Los Angeles after all and sweat begins to bead as abstraction is traded for sensation. The Grammy-award winning director oscillates between fatherhood, soggy cereal and a full-house in the face of COVID-19 and chatty meetings surrounding the debut of Clark, a new, Netflix show he co-wrote about a Swedish libertine whose crimes forged the spine of the term Stockholm Syndrome before carving out some time to chat.

Having worked in the industry for almost 30 years now, Jonas has established himself as a prodigious, music-video director capable of wielding a colossal range spanning across genres and decades before situating himself more comfortably in writer’s rooms and director’s chairs on sets of feature-length films. “People expect me to take them out of their comfort zone, they expect me to have a voice,” says Jonas. Mind you these “people” include the likes of Beyonce, The Rolling Stones, The Prodigy, ABBA, Dior, Paul McCartney, Madonna, Givenchy and Lady Gaga. His most recent film, Lords of Chaos (2018),showcased a sublime bridging of his raw sensibilities with the creation of the kinds of omniscient visual languages he is known for. Yet as he unclenches and clenches his fists again, peering down into introspection, Jonas shies away from what we think he is looking for. Remaining wary of success because it is too often a ceiling, he is still learning to use his wings, coasting on the jetstreams of his own creativity. The legacy he is building values hindsight as vision and resilience is the only feeling he is chasing with arms outstretched, grasping, reaching.

You’ve got such a distinct style and have worked with such a wide range of clients in the entertainment industry ranging from music, to film, to fashion, garnering much awareness to your visual world but we wanted to give you more of an opportunity to talk about the experiences and perspectives that shaped your lens — more so than just your lens itself. When you were a child, where did you get your ideas about the future from? Can you think of any particularly formative experiences from your childhood that you can remember?

Growing up in the seventies and eighties was probably the best time to grow up in. I wouldn’t wish that I was born 10 years earlier or 10 years later. Everything was just perfect, especially from a cultural and musical perspective because all the best music came out of that era. This was a time when bands did an album and a tour every year and for some weird reason they always came to Stockholm. Music was a big deal in my life since my early teens I would say and it was really one of those things where people just picked up the instrument and did it. I really thought that I would work with music but I was always drawn more to the visual aspect of it. I was the guy who came up with the name, I was the guy that made the logo, I was the guy that thought about where the instruments should be on the stage. I didn’t know back then, but I realize now that I wasn’t a very good musician. I was always a film guy, always loved films and I had as many film posters on my wall as I did with music posters but it wasn’t until I did military service where for some weird reason, I ended up taking pictures for an army magazine of sorts, that I realized for the first time in my life, I had a lot of confidence. It was the most natural thing in the world for me and almost in an instant, I stopped playing music. When I discovered film editing specifically, not just photography, it was like I met God. Mt first year in production I was an assistant to a director who was very, very skilled in editing, very ahead of his time and we’re talking early nineties here. A lot of his techniques and a lot of the way he prepared for a shoot and put stories together was to always have the edit in the back of your head, that’s how I learned. I never stopped hanging with musicians and I never stopped loving music but my focus quickly became the fact that I was the guy with a camera instead of the guy banging the drums.

Right and thinking about music as a whole, there’s obviously such an emotional release or sense of catharsis that is innate to it. Examining the editing process, that’s seemingly how you shape and communicate emotions visually. I’m wondering if you can give verbal form to your own visual language and explain how editing renders the emotionality that goes into music and film as a whole.

I think what I discovered was that I was very limited when I played music because I didn’t really write songs or lyrics, but what I learned quickly with editing was that I could easily use small details to change how you looked at something. I could move a frame or two and you see the whole thing completely different. I could add a sound effect and all of a sudden it’s scary, add another sound effect and you would feel something else entirely. It was incredible, it almost made me feel like a magician to see how I could manipulate people to think and feel with my edits. I still love that and unfortunately when you make music videos and commercials as I’ve done with the bigger part of my life, you never get to see your audience and experience it with them. So when I started making movies and had the chance to be a part of the audience and to watch their reactions, I couldn’t get enough of it. It was so interesting to feel the shifts in emotions, moods and energy and how what I made would move them around.

Right and with art as a whole, some people want their art to be “understood” verbatim, they want their audience to know what the message is that they’re trying to communicate and for them to get it. When you’re in the audience watching their reactions, is this what you desire? Or are you open to having people feel what they’re going to feel and walking away with their own interpretation of your work? How in control do you need to be?

I mean we always have a vision and we always have an idea when we set out to create things. For example, I remember so clearly thinking that when I did The Prodigy’s music video Smack My Bitch Up, that it was funny. I thought it was a comedy and I showed it to some friends in Sweden and they were laughing their asses off so when it came out, I couldn’t believe the reaction and that it upset a lot of people. On the flip side of that, I remember when I premiered my movie Spun at the Arc Light, which I actually thought was a pretty serious movie, that during the first scene everybody was laughing and I’m like, why are people laughing? This is serious shit. It took me years before I realized that Spun is actually a comedy. But especially now when I’m writing, I always have an idea of where I want to go with it. I’m not just doing it and hoping for the best but it takes years before you learn to see stuff for what it is. Even for my video Ray of Light [with Madonna which he won a Grammy for in 1999], it took me 10 years before I was proud of that video. I thought it was way too simple and I remember coming back to Sweden after I made it and I didn’t want to show it to my friends because I thought they would say, ‘oh, so you go to America and work with Madonna and this is what you come back with?’ It took me years before I realized that that’s just the best package ever, that album, the Mario Testino pictures and when I was in that moment, I couldn’t see it, you know?

Right and is that frustrating at all or are you now resigned to the fact that some things are just better seen with hindsight? Does it mar the experience of making it?

Yeah, but it goes the other way too because sometimes I’ve done what I think is some of my best work and people didn’t really respond to it or didn’t even watch it. Timing is something you cannot plan.

Do you mean like the cultural timing of what people are going to be thinking or have references to in that moment of a project’s release?

Yeah how you release stuff, how you market stuff, it’s all so sensitive, you know? I think we all know that feeling of when we discover a movie that we’ve never seen before and we ask ourselves ‘why didn’t I ever see this movie?’ It’s not a given that just because it’s good, that it’s gonna work or be successful, you know? We also know that some really bad stuff is making it big simultaneously. We can never learn a way to control that, it’s impossible. In my point of view, all my favorite artists, my favorite directors, favorite musicians, they all fail once in a while because they’re brave and they choose to believe their gut feeling and go with it. I’m not a big fan of these smart artists who always get it right, if you know what I mean. [laughs]

Yeah because then creation is coming from a place where it’s for others instead of yourself, it becomes unhinged.

Yeah I think so. Obviously with a lot of my jobs I’m the director for hire so I always need to think about my clients and the artists I’m working with since I’m ultimately there for them.

Definitely but when you are working with clients who may not align with your aesthetic or your vision per se, what are you willing to compromise on? Where do you draw the line?

That’s a tough question. Number one, I’m really happy and blessed that I get to work with brave clients and artists who really want to make good stuff. Number two, I kind of ended up being the guy to go to if you want something special, so people expect me to take them out of their comfort zone, they expect me to have a voice. Often times with commercials, my job is to understand the DNA of the company and product and to figure out what it is they want to do and that’s half the battle. I’ve always kind of done the same with music videos and out of my 300 music videos or so, I don’t think I ever was on an ego trip. I just try not to do what they’ve done before and pull them out of their comfort zone without making them feel too far away from who they are. It’s kinda my job to push it a little bit.

Right. The idea of comfort zones is really interesting because they seemingly are the boundaries to our own identities and affinities. In taking your collaborators out of their respective comfort zones, what does that process really look like for you?

I mean, it’s so different from time to time. There’s not a manual for how it goes down but I think it’s a mixture of several different things. One of them is the fact that I don’t like to repeat things and I always try to do something that’s never been done before. Especially in music videos, if you take a specific artist, usually you can backtrack easily and see what they’ve done. It becomes about balance and you always have to stay within the DNA of what the artist is all about. You can’t just take an artist and put them in a clown outfit and say, this is something different, you know, it’s got to be within their ethos. So sometimes when I say to take them out of their comfort zone, it could be the tiniest push that could take them there, it could be as simple as a hat. Some artists have been pushed in so many different directions that it’s really hard to come up with an idea that will make your approach to them different in the sense that is illuminating. I have often found that it’s sometimes about simplifying stuff, it’s easy to hide behind what’s big and gigantic. My strength is usually to listen to the music and figure out what the timing is, what the song is about, whatever it is. From there I’ve found the best situation is when the artist has some sort of initial thought that could trigger an idea for me, it cascades from there. Sometimes a blank canvas is not always the best idea, it’s nice when it becomes about dialogue.

Especially with music videos and performance in general, you really do get to play with the idea of multiple selves as our identities because it’s always changing. Do you too feel like you get to play with the duality of performance in terms of your style and your own relationship with yourself?

Well it actually used to trouble me a little bit because I felt like I didn’t have a style. A lot of my favorite directors and photographers that I’ve always looked up to had such distinctive styles and specific things to where you could see a mile away if they had done something. Meanwhile, I felt like I was going too broad. One day I was doing an H&M commercial with children’s clothes and the next day I was doing an Ozzy Ozbourne video. It actually took me a few years to be proud of the fact that I could do that. I also realized that it fuels me, to where one thing leads to another, one thing makes me more inspired. There was also a time when I was really snobbish with music videos, I turned down stuff because I personally didn’t like it and that became such a limitation for me. I remember clearly when I said ‘yes’ to work with Christina Aguilera because I had said that I wasn’t going to work with any of those pop artists. When we did the video for Beautiful, it was such a life changing moment for me because it really made me think that I should say yes to stuff. Now I realize that 25 years into my working life that a lot of these fantastic, life changing moments have been a result of me saying yes to stuff instead of saying, no. Sometimes I joke that I built my career on saying yes. [laughs]

Right and I feel like so much of that comes from being naturally empathetic as it allows you to move easily between realms, genres and contexts while knowing what you bring to the table as a director in each scenario. I feel like it also fuels growth and ultimately longevity that hinges on a strong sense of resilience.

You wear so many different hats and I actually feel younger than ever as a director even though I’ve done it for so many years. But you do get to a point where every problem and challenge you face is kind of something you’ve encountered before. There’s a reason why a lot of big directors not only have a long career but that they also get better and better. With most professions you kind of get weaker as you get older but as a director and a writer, you get a little smarter and you begin to approach challenges in a smarter, calmer way. I still see that I definitely have the best ahead of me. I now have confidence as a writer which I never had before in my life and there’s a lot of things that happen to me as a director now that makes it easier for me to take on things. I also think it’s an addiction. It’s such a rush through your body when you’re done with a project, you get the same rush each time you get a new idea and every time you start up a new project, it’s amazing. A lot of these big directors could have stopped years ago and lived pretty good lives and then there are those who stop because they don’t have more to give. I feel like I’m spreading out my creativity over my whole life because I have always seen myself as a slow starter.

But ultimately you cannot be a filmmaker without being some sort of businessman and understand that somebody is paying you. Unfortunately, filmmaking is not something you can just do for fun because it’s so expensive to make films and it involves so many people. Sometimes you’re sitting with an idea for years that may never happen. I was thinking of Lords of Chaos for 15 years before I got to make it. It is a weird lifestyle if you try to explain what it is you’re doing to a normal person. There’s always a risk you take because you can work so hard for so long and even then it might not even happen, it’s never a safe bet.

Yeah and thinking specifically about projects like Lords of Chaos, previously you used the phrase expectation of voice in relation to your work and I think that’s something that is an interesting hallmark. You were able to essentially turn a rather harrowing account of coming of age and tarnished dreams into a story of brotherhood, vulnerability and relationships.

Lords of Chaos was a journey even for myself because it didn’t really start it off like that initially. I thought I was doing a movie about black metal, what happened in Norway and the church burnings and all of that but it actually took me all the way to the edit to realize that this story is about the relationships between these three boys. A lot of people had already decided what Lords of Chaos was gonna be about before they saw it and they were surprised when they did see it because it wasn’t what they expected. We all think we know the story better than everybody else, but nobody ever talked really about the fact that these boys were young and there was an extreme bond between these three boys. I guess the biggest lie of that movie is me thinking that I knew how they felt and the depth of the other relationships they had. I can imagine how they felt and I can imagine how horrible everything was but it’s really hard for me as a director and writer to know for sure. That’s originally why I added based on truths or lies to the opening of the film because the point is that we’re walking right into the privacy of these young boys and their families and all the relatives that are still mourning and it’s fucking sad.

Right we touched a little bit on how getting into writing was also a big deal for you. There’s a certain door to vulnerability that is opened with writing in general. Can you talk us through the process of getting to know your own writing voice and what it means to tell someone else’s story through that voice?

Historically writing has been a struggle for me because I’m very dyslexic. I grew up in a time when this dyslexia was seen more as a handicap but today the approach to it is a little different. It was my biggest nightmare when people asked me to write down my ideas but when I started to work in America and write in English, I always figured that it was okay to write a little wrong because English is not my first language. It actually gave me more confidence because I felt like the margin of error was excusable and it was like if you don’t understand, you can ask me, you know? In filmmaking, writing it’s the hardest thing in the world and so often you are starting from scratch. For so long I’ve respected it from afar but I didn’t realize that’s also actually what I do. Even if you write something that’s four minutes for a music video, or 15 minutes for a short film or even 30 seconds for a commercial, you’re still a writer, it’s still the same challenge and who knew that I had been doing it for so many years.

When I was going to write Lords of Chaos, I had to remind myself that I already had it in me so when I finally sat down to do so it came so fast, it just poured out of me. I wrote the first draft in a few weeks. I brought on Dennis Magnusson, who is a dramaturge, because sometimes it’s very lonely to write and it’s always great to have a second pair of eyes. Dennis really helped me to work through some of the story plots and we added the voiceover featured in the film together. I know exactly what my strengths and weaknesses are when it comes to writing, for instance I’m really good at adding tone, writing dialogue.

A project that I’m working on now is writing this series for Netflix with two other guys. I would say it’s one of the most fun things I’ve done in my life. It’s a six-episode, limited series but it’s basically like making three movies in a row. It’s based on Clark Oloffsson who is a very infamous criminal, bank robber and womanizer who has been called Sweden’s first “pop-gangster.” He was present at the Norrmalmstorg robbery whose events resulted in the creation of the phrase “Stockholm syndrome” to describe them.

That’s super exciting! When you’re collaborating with other writers and having to know what you bring to the table, what do you think makes you good at things like dialogue, tone, those sorts of very nuanced things?

Oh, wow. I have no idea. I just always liked to study people, listen to how people talk, walk, dress differently on all fronts. I’ve always been a student of human behavior and with some of my friends, it’s all that we talk about. I’m not very educated but I got a big portion of common sense in my life by being street savvy and a lot of the things that I pick up when I write jokes and stuff is from real life.

Right and especially being as established as you are, to have this idea where you are still learning from those around you all the time is remarkable. With that in mind, whose opinion matters to you? Where does validation come in?

I’m a pretty good listener and somebody could say something about something without not even meaning it and that could take me down a mental rabbit hole of something else entirely. Those words could come from anywhere, a comment, or a question about something I did and then suddenly I understand it or see it from another point of view. When I’m working on a music video, I’m so blessed to work with creative people and their input makes me better and takes me to places where I didn’t think I could go. Madonna being my number one example of this because we have such a history and she also caught me during a time when yeah, I had been working for almost 10 years before we met, but I didn’t know much. She brought me into scenarios that I never thought I could do and opened my eyes to the fact that you as a director have the right to change your mind or that you have the right to ask questions and that you can ask for a lot, but you always ask most out of yourself. I look at all of these amazing relationships I’ve had throughout my career and I’m always learning something from them. I never really shut anybody down and try to take everything in. I also have my crew around me, some of whom I’ve worked with for 30 years or so, I’m kind of a long relationship type of guy.

I love the longevity in terms of working relationships, there’s a respect for time and real growth. It’s interesting if you begin to look at the upcoming generation of creatives who are shaping the music scene in a totally different way today and there’s an overall feeling of transience, a constant rush to produce. Is this new generation as influential or as inspirational to you as the one you grew up in?

It’s so hard to say, I’m always kind of like that grumpy old man who thinks that everything was better before, especially in music. I try so hard to listen to new music but I always go back to the old stuff, it’s just who I am. I don’t have many references anymore, period. I’ve gone through all types of different periods of my life. There was a time when I was hugely inspired by fashion, photographers, I used to read all the magazines, watch all the movies and after a while you just stop that and you start to go back to yourself more. That’s the biggest growth creatively that I’ve ever felt, to stop feeling like I needed to know what other people were doing and to start to think about what I do. That’s a huge thing in your life. But I think creativity in general is blooming bigger than ever today. I have four children so I see what’s going on and it’s incredible. It’s so easy to be creative and do all these amazing things instantly. It’s amazing to see what everybody can do at home with their phones and they actually do it. I think it’s inspired them to do even more.

Right and I feel like why your work is so successful is because there’s this strong presence of originality and nowadays we are always grasping for another reference, always on social media looking at what other people are doing and being influenced by it. What allowed you to find peace with your own creativity, to turn inwards and to not feel the need for references despite having to produce all of these ideas and create?

I find it a good compliment and a good question all in one, but I don’t really know how it happens and when it happens. I think you’re born with a certain amount of creativity and you have to make sure that you use it well and use it smartly. I was always so insecure in my creativity up until a point where it suddenly felt easier for me. I feel like if you are insecure, it’s so easy to look around and see what other people do. I know how easy it is to be influenced by the world around you and how easy it is to want to do what other people do when it’s great. I know how easy it is to step into those traps but I can tell when I look back on my career what the different sources of inspiration have been, and where they’ve come from, I’m aware of that. It’s not like I’m not interested in what other people do anymore, or it’s not like I’m not still a student of creativity, but I’m not influenced in the same way. I don’t pick it up. I get influenced by other stuff. You know, it’s like I get influenced by a feeling or I get inspired by something someone said, I get inspired by a smile or the way something looks. I think it’s just a natural part of development and you should be really happy if you get there. The fact that I still leave the building at the end of the day, working on my confidence and see things as part of a bigger picture than I used to do, is ust a healthy thing for my work.

Yeah and where do you draw the line between influence and inspiration?

That’s a tough one. It’s a fine line between and my fear is always that if I start to analyze it too much, I’m, I’m worried I’m gonna lose it . For example, take Stephen King’s book, On Writing, I bought the audiobook and I listened to Stephen reading it himself and it’s just incredible how he speaks and how he talks about his writing process but I had to stop listening because I was worried that I was going to learn something from it that was going to ruin my own way of writing. I never went to school, I’m not technically a good writer in any way, but the ideas, scenes, the characters and the jokes, still pour out of my hands and I was just thinking, I’d rather have that than to learn how to actually write, you know? I couldn’t finish the book because I was worried that I was going to be too caught up in those things, trying to pretend that I’m Stephen King and writing the way he does, which is never gonna happen anyway, so I was like, okay, I’m not gonna do this.

Definitely and how do you define success there? What kind of emotions do you want it to leave you with, audience aside?

I mean when you do as much as I do, the hallmarks of success could come in so many different ways. It could be an extremely happy client. It could be that the product really worked and we sold a lot of stuff. It could be that we had 10 million downloads in the first three days. It could be the sense of fulfillment and desire to share. There’s not one answer for it. The one thing that keeps it all together for me is knowing that I did the best I can. The worst thing in the world for me is — even if the project was a success by another markers — feeling like I did a sloppy job. Even if I made a film that might not be that great, if I did the best I could do, that’s still a success for me because it still leaves me with a good feeling. But then again, it’s so hard to really define because when you’re in the moment you don’t really know how to gauge it outside of feeling. I can list the 10 moments in my career that took me further in life, or my 10 biggest hits and it’s easy to see them now when I’m looking back. But you don’t really know when you have success on your hands.

Right so what do you think endures and is it important for you to leave a legacy?

I’m not there yet, but it seems like the older you get, the more keen you are on these thoughts. Every artist that I’ve looked up to has some sort of book written about or by them, they’ve done work on a biopic or documentary and then if they’re lucky, there’s a movie about them. That’s what people seem to do but I’m a behind the scenes kind of guy and unfortunately my art is not meant to last. Movies don’t have the lifespan that music could potentially have or books could potentially have, movies get old, they often lean more towards entertainment and the present moment than art. I’m lucky that I have a few music videos that people remember but that’s not the purpose of them, they’re really just tools to create a moment that is now and then never again. I’m not meant to be remembered. I’m meant to entertain you now and that’s it, you know?

And is that okay with you? Is that what you want?

Yeah, I think it’s okay. Even some of the biggest filmmakers in the world are going to be forgotten unfortunately and that comes with the job. It’s more so just about telling the story and having it be understood. I can’t speak for other people, but it’s all about learning, moving forward and seeing past things to see the bigger picture. The worst fear in my life is to not be able to see beyond what’s in front of me. I always hope I’m learning. I hope I’m becoming better and I think about it every day and I think that goes for the people that are around me as well.If we understand that everything we do has an effect, and if we can see the bigger picture, that makes it easier.

Credits

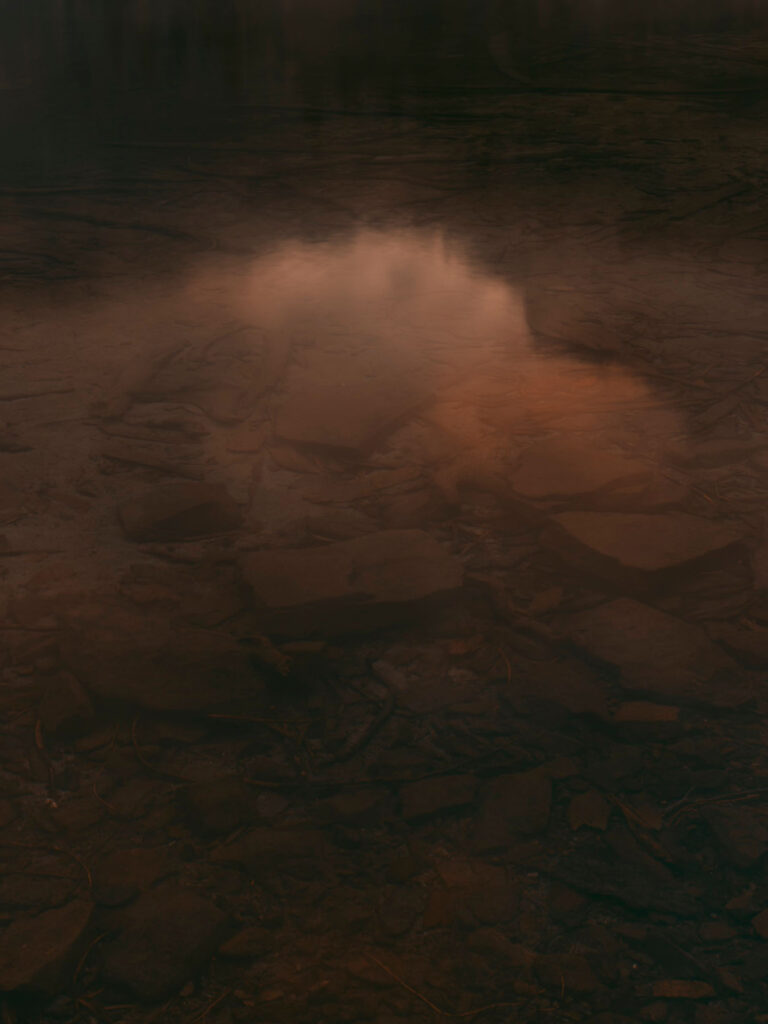

Photography · Cody Cobb

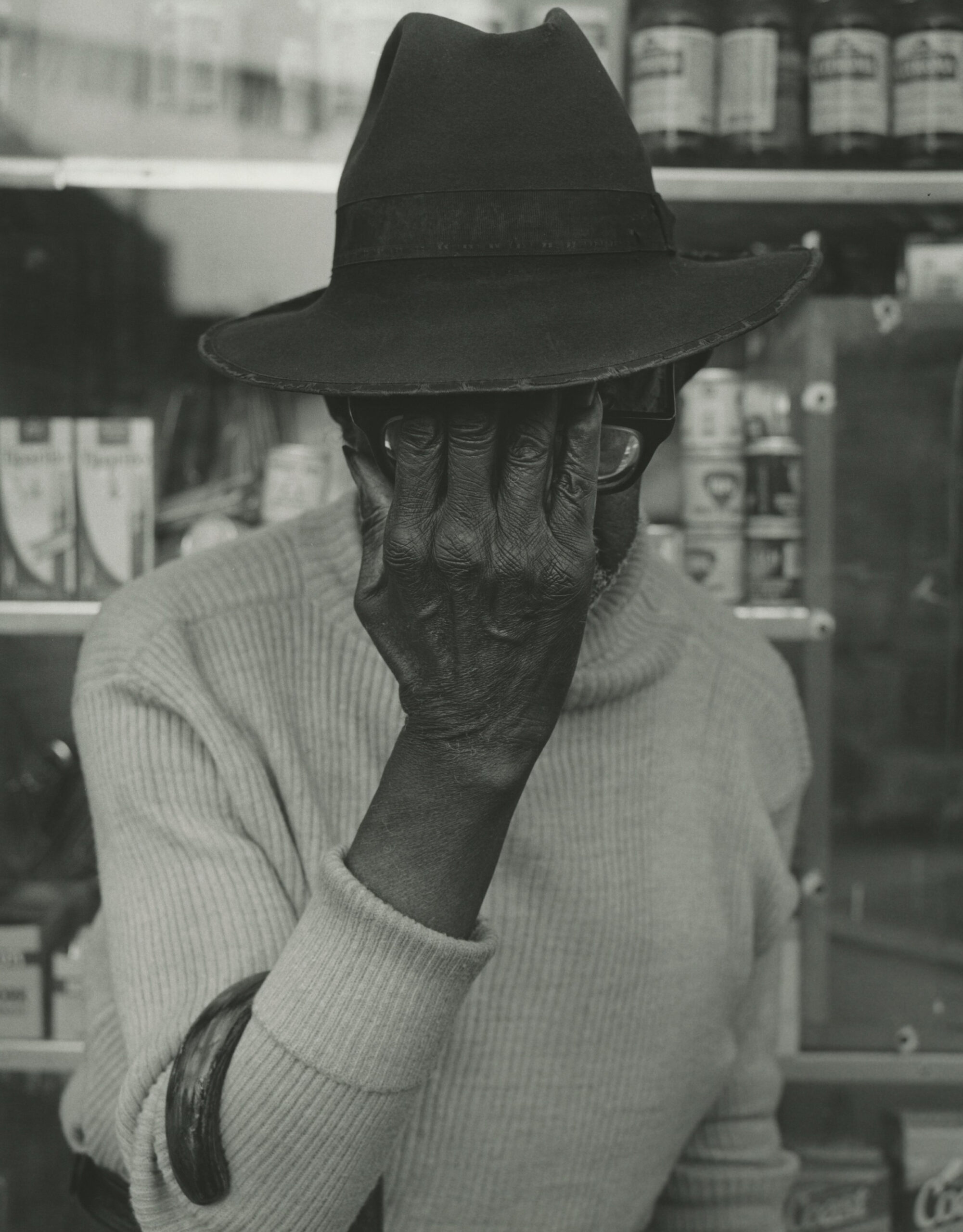

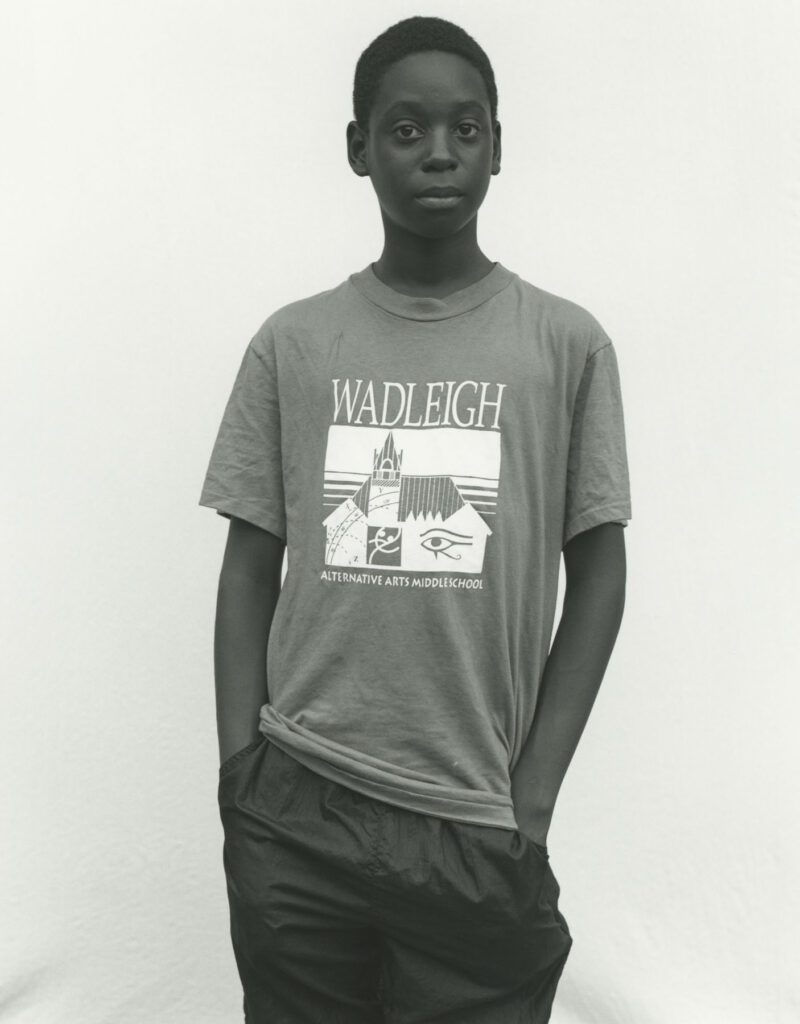

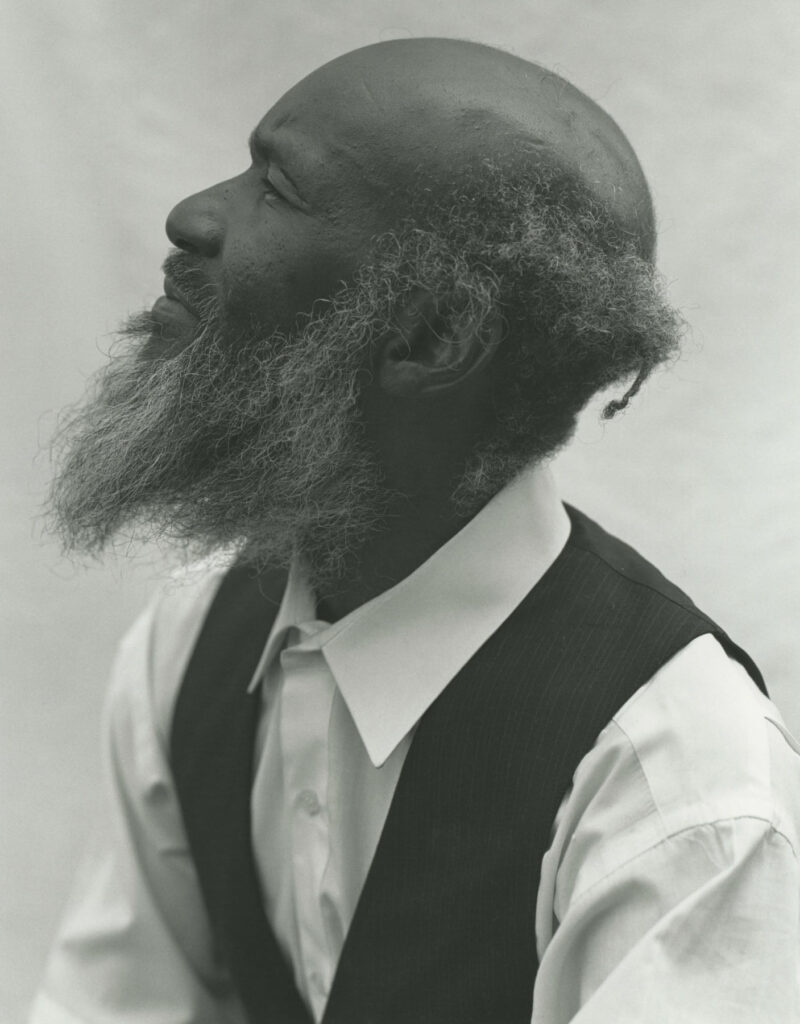

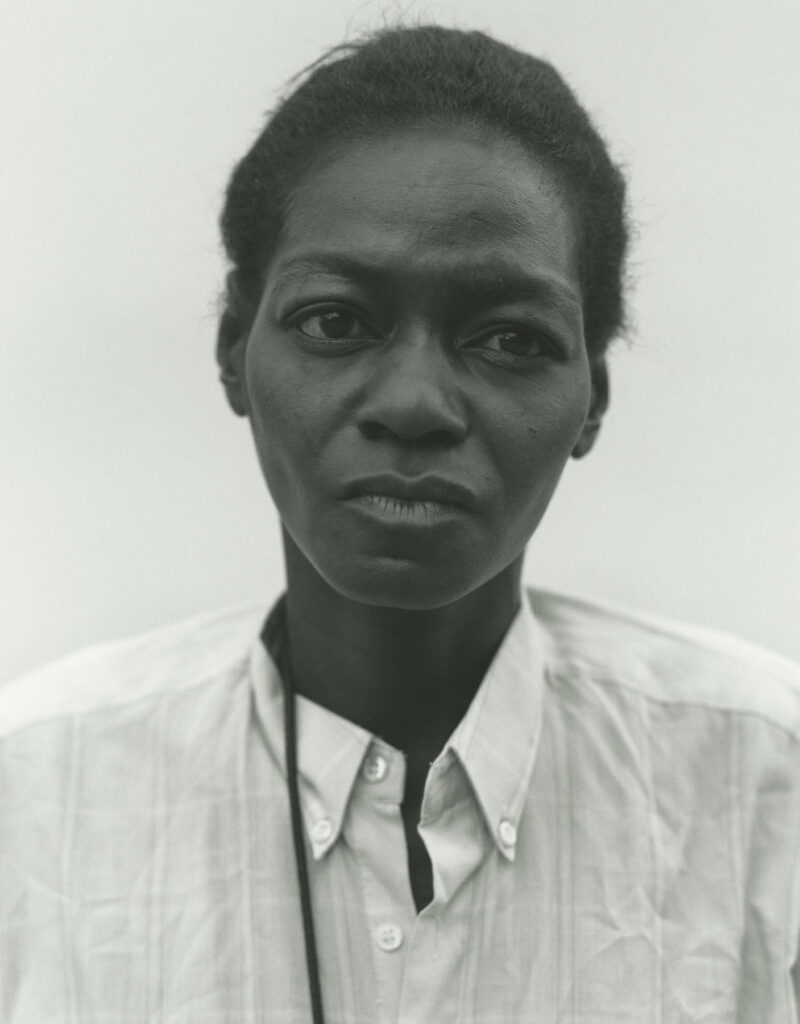

When Katsu Naito arrived in Harlem in 1988, it took him two years before he would begin taking photographs of its residents. It would take him a further twenty years to develop the negatives – a decision he consciously made. The photographer was cautious to build up the trust of the community before pointing his camera in their direction – demonstrating a careful consideration and tenderness that radiates from his work. Sensing that Harlem, which was still recovering from economic devastation from the 1970’s, was in the midst of unprecedented change, his body of work from the nineties offers an insight into a lost neighbourhood. These images make up ‘Once In Harlem’, which captures an extraordinary level of trust between Naito, as photographer and, ultimately, ‘outsider’, and the people who stand in front of his camera. Similarly, the body of work ‘West Side Rendezvous’, published in 2011 but taken around the same time as the Harlem work, evokes the emotive quality that make Naito’s images so compelling. The mutual respect between Naito and his subjects – in this case, transvestite and transsexual prostitutes in New York’s meatpacking district – is timeless, even if the run down backdrops have long been replaced by gentrification. Naito moved to New York from Japan in the mid-1980’s, having secured a job as a chef. Inspired by the street photography of Diane Arbus, a colleague introduced him to his first Leica camera – to this day, Naito explains, he still shots in black and white analogue format.

NR: The photographs from your book ‘Once In Harlem’ are all from the early nineties, but were only recently developed; why did it take so long to develop them, and what surprised you the most from seeing these images for the first time?

Katsu Naito: There were a few reasons it took so long to be published. I worked in Harlem as part of a personal assignment between the late ‘80s and early ‘90s – and I always knew that I wanted it to be published in years to come. Harlem had started to change; towards the end of the ‘80s, abandoned buildings were being given a second lease of life, as parking lots or renovated buildings. I was living through all of this, and I wanted to share these images of Harlem when people had forgotten about it. This was the main reason that I kept the negatives in a box in the corner of my darkroom. I started working towards printing in 2013, going through many test prints in order to find the right quality for the final print – this took a long time.

“I try to put life into the print, as I think it’s important to seal emotional quality into it.”

I really felt the power of photography after printing this series – seeing how these plastic negatives could bring back to life an image after twenty years. As the images started to show in the developing tray, tears dropped onto my cheek, from the surprise.

NR: As a photographer, do you feel it is your responsibility to document the lives of groups of people who can get forgotten amongst society?

KN: I feel strongly about that. People on the edge of society have hidden beauty in their heart, a quality that’s hard to draw out – but it’s something that I wanted to capture with my camera.

NR: Having moved to New York in the 1980s from Japan, did photography give you a sense of control over being in a foreign environment?

KN: Carrying a camera gave me a license to be on the street; it can break language and cultural barriers. It can give control, but I do also believe that it’s necessary to have trust between both parties.

NR: When taking someone’s photograph, what do you look for in their self-presentation?

KN: I only ask the person to stand in front of my camera and communicate through their composure, I often ask myself “how close can I get?”

“There’s a moment of unawareness towards the camera; when I feel that, I start taking photographs.”

NR: What role do the people in your photographs play; are they a part of the composition, or does the act of taking their photo establish a connection with them as a person?

KN: It’s both; the composition and an emotional connection with the person is very important for me. But this must happen in an organic way – a connection with them must come first.

NR: Has the way people respond to being asked to have their photograph taken changed at all over the years?

KN: I don’t expect people to accept my offer of being photographed. In the instances when the answer is no, I wouldn’t chase them for a photograph. This doesn’t happen often though – for some reason almost everyone would say yes to my camera.

NR: As for the way you approach taking a photograph; has that changed over time?

KN: I must be comfortable enough to walk the area. If I’m not comfortable, I can’t make my subject comfortable, so location scouting and understand the atmosphere in the area is the first thing I do. It can take an hour, or months, depending on the project.

“This is the way I have always approached the way I take photographs, ensuring I respect my subjects. This hasn’t changed, and it will never change.”

NR: Why is shooting in black and white important to you?

KN: I only work with black and white film, that I process in my darkroom. It’s necessary to have total control over every step of the process – and I think, most of all, shooting in black and white is the only medium that really emphasises three dimensional reality in a two dimensional format.

NR: What is the most valuable thing you have learnt from taking people’s photograph over the years that you have spent photographing New York?

KN: Living in New York City can be like riding an emotional rollercoaster every day. The fundamental aspect of it, though, is simply the human element.

NR: There is a timeless quality to your work; is this deliberate? And if so, is it a crucial aspect of the photos you take?

KN: Yes. Something that is always on my mind is making photo sessions simple. The person is in front of my camera and they are the main subject. I wouldn’t want to add any meaningless props unless they are already there, and the person has a natural relationship to them. I wanted pull out what they have inside of them.

NR: In terms of having control over an image, how does the process of analogue photography compare with the instantaneousness of digital photography?

KN: There is a quality that I can’t describe with words that can be seen in a gelatin silver print. I often call it “capturing the air”, or “capturing the temperature”. I think it’s is difficult to see this type quality in digital photography.

Credits

Photographs · Katsu Naito from his Once In Harlem series

https://www.katsunaito.com/

Words · Ellie Brown

Team

Photography Mehdi Sef

Fashion Coline Peyrot from Opos

Makeup Emilie Plume from Carol Hayes Management

Hair Carole Douard from Call My Agent

Model Rachel Marx from Supreme Management Paris

Designers

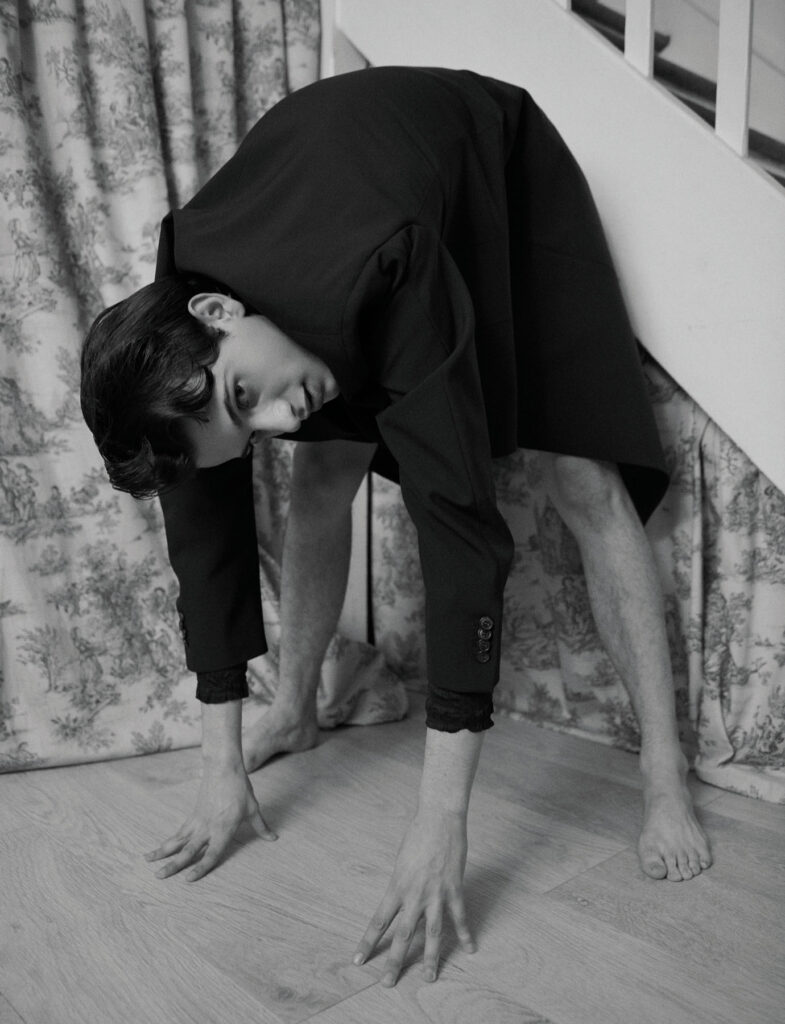

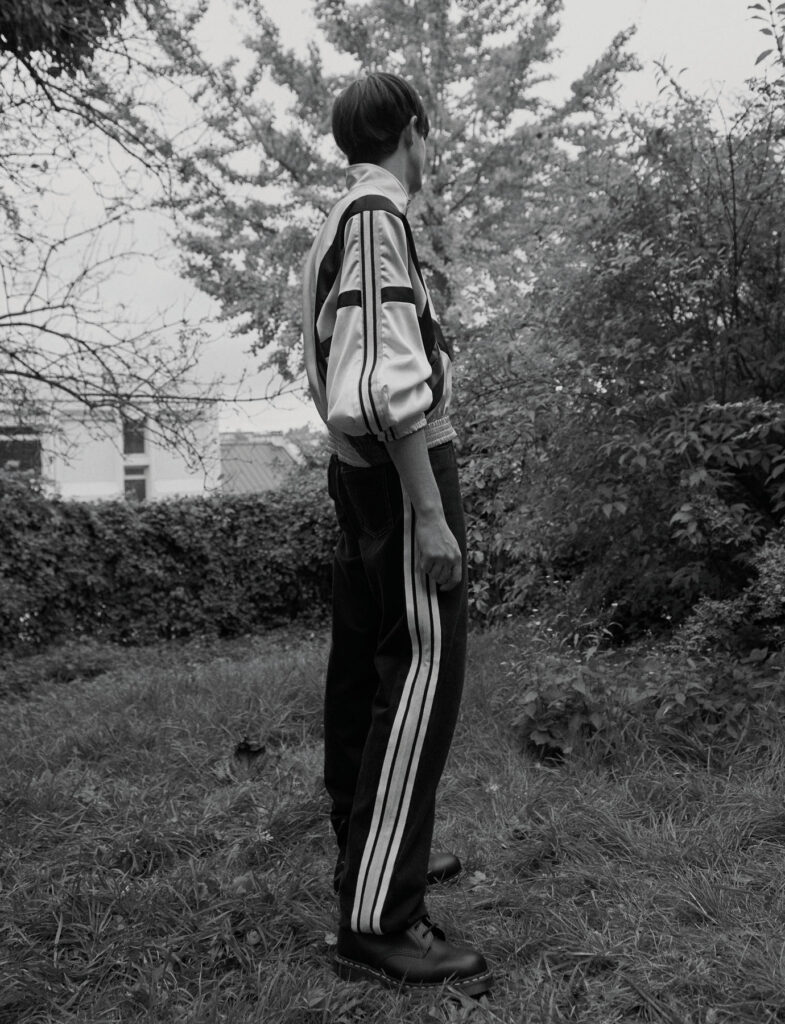

Team

Photography · Niklas Bergrstand and Mateja Duljak

Fashion · Arthur Mayadoux

Make-Up · Rikke Dengse Jensen

Hair · Nicolas Philippon

Fashion Assistant · Victoire Seveno

Models · Augustin and Luca from Success Models

Designers

It’s the small details that capture attention in the work of Paul Mpagi Sepuya – the evidence and lasting presence of human encounter, finger prints and smudges on glass, for instance. Though the photographer works only with a digital camera, there’s a certain tactility that lingers in his work.

Relationships come to the forefront; Sepuya’s work centres around friendships, intimate encounters, muses and himself. The notion of the ‘dark room’ (which has been referenced both in titled works and in solo installations) lays claim to ambiguity – it both refers to the place in which the photographer creates, documents and develops, and it is also the space of homoerotic sexual exchange. The lines are, at once, blurred and clearly demarcated. In the absence of interpreting the dark room in terms of its analogue definition and purpose, Sepuya ‘develops’ his photography through a process of collaging, layering and re-production. A photograph becomes a multi-layered image, further distorted by the presence of mirrors that are often the focus of the camera. It’s difficult, at times, to ascertain what is what: within a single work, fragments of figures and moments in time are often combined. None of which is accidental; such an amalgamation of displaced aspects come together as a multifaceted study in portraiture.

Throughout Sepuya’s work there’s a critical awareness of the role that his camera plays in capturing time and its implications on human interaction – something that is quantified by the inclusion of his work at MoMA’s distinguished ‘New Photography’ exhibition under this year’s theme ‘being’.

NR: Some of your photographs address individuals by name in the title, others refer to a figure or figures; is there a logic behind the distinction?

Paul MPagi Sepuya: My earlier portrait projects, beginning with Beloved Object & Amorous Subject (Revisited) from2005 – 2008, and the other portraits up until 2014 were all titled by the name of the individual or subjects. I don’t photograph models and there are friendships, collaborations and at minimum social acquaintances with everyone at the beginning of or working together, it was important for me to ground the work in that social space. As the individual portraits moved into the world, and into various studios I was working in (the earlier works were photographed in my home), the titles came to include the date and location of the photograph. Those photographs could be portraits, or me re-photographing materials in my studio which gave way to a “collage” type style, though the work was never collaged.

Figures came into the work when I returned to Los Angeles for grad school at UCLA. Reconstituting materials through arranging them on the surface of mirrors that I would photograph in front of my tripod-camera allowed me to create compositions *about* subjects more loosely, and so the number of figures noted corresponded to the number of subjects in the fragments that made up the complete picture. Currently, I have left behind names from my titles. Each work is titled by the project that it inhabits (Mirror Study, A Portrait, Studio, A Ground, etc…), and the name given the file capture in camera.

“I’m interested in emphasizing the inside-outside aspect of recognition within this ‘dark room’ space where, like all of my work has been positioned, it is the meeting points of queer and homoerotic creative, social, and sexual exchange.”

NR: How do you relate to the people in your photos, when their bodies appear fragmented and abstracted?

PMS: I know every fragment, sliver of space or edge of a table that relates to a figure not present. That’s to say, they are never fragments or abstractions because, indexed alongside them in a larger project, are the notations that tie them to the full portraits. I make a point of saying that;

“no subjects are left to fragmentation and abstraction in my work; there is always a full portrait of each subject.”

NR: What is the appeal of digital photography for you?

PMS: It’s efficiency for my process, that’s it. I am strongly against the digital manipulation of my pictures, or creating/assembling pictures through digital collage, etc. The material that is arranged, cut, and affixed on the surface of the mirrors comes from the in-process materials in my studio. So to be able to photograph, print and re-photograph within a single space is important to me. It’s a method that began during my residency at the Center for Photography at Woodstock in 2010, and I have used in various forms since then.

NR: If taking a photograph can capture a specific moment in time, how does your practise (from taking a photograph to reworking and collaging it) relate to notions of time and memory?

PMS: I am less interested in moments in time (which I associate with the outside world) than with the “collage of compressed time” – or something to the effect that Brian O’Doherty speaks of in Studio and Cube: On The Relationship Between Where Art is Made and Where Art is Displayed. He describes studio time as placing all material in the present, within the reach of revision and remaking by the artist’s hand. That is how I associate the process of portrait-making with the real-world relationships that make that production possible.

NR: Can the context of viewing your work as part of a wider exhibition influence the way the pieces are perceived? And add to their development as ‘works in progress’?

PMS: Yes, indeed. All of my work is made toward the consideration of a grammar and visual rhythm, whether it’s content, formal elements or scale, in relation to my larger body of work.

NR: What is the allure of the physicality of photography (when it’s printed out to be used for collages, or when it’s featured in zines or books)?

PMS: Images can’t just free float. I am invested in the handling pictures, having to contend with them physically. I started by making zines and books, and with the current “collage” works,

“it is important that I am inherently a part of the image during the process of their making.”

While I work, I am within the reflected space of my studio.

NR: What, if anything, do you want the viewer to take away from your work in regards to queer and black identities?

PMS: Absolutely nothing as far as identity may be proscribed. But everything as far as the materiality and sociality of queerness, homoeroticism, and blackness as requisites for a kind of knowledge and experience otherwise obliterated by whiteness and heteronormativity.

NR: Your photographs often allude to the presence of people no longer present in the frame, from fingerprints in the mirror to abandoned orange peel; what is the significance of the documenting these aspects?

PMS: Whether a subject is represented through pictorial representation in a straight-up portrait or not,

“I want the images to include an indexical mark of the social world from which it comes.”

These traces of real people can’t be faked. They are like smoke to fire. Funnily (or frustratingly?) enough, someone once asked me about the “smoke” in the photographs and I had to correct and say, no they are *another* kind of trace. They are the smudges of bodies – my own and others – as we work to make the images.

NR: The photographer’s studio connotes a sense of purpose and control over the subject and the outcome, is this something that you consider or navigate through your work?

PMS: Since I first started working in a studio and became fascinated by the possibilities therein, it’s become a site for me that really amplifies my presence, in thinking about the history of that control asserted by the artist along with the loosening of social and sexual morality that becomes permissible in that space. The permission that, within the world of the artist, is given to re-arranging and representing desire.

Photos

Credits

http://www.luiscorzo.com/

Photos

When thinking of some of the iconic stars of the 20th century, it’s likely that an equally iconic photograph of them has been taken by Terry O’Neill. Having inadvertently found himself at the epicentre of the glitz of the swinging sixties, O’Neill cut his teeth amongst the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

Born in London, he had wanted to be a jazz drummer, and, accordingly, took a job with British Airways as a photographer, with the ambition of working up to a flight attendant which would have allowed him four days a week on the ground in New York – and a way into the jazz world. Yet, a chance snapshot of a sleeping man, who turned out to be the then-home secretary, RAB Butler, gave O’Neill an unlikely way into photography. His embracing of an emerging youth culture is a testament to his distinctive eye; working ahead of the curve, both his subjects and images alike would come to have resounding influence.

Over the course of a luminous career, O’Neill has worked with legendary names – from Frank Sinatra, and Audrey Hepburn – to David Bowie and Nelson Mandela. Across an extensive oeuvre, the unique partnering of star power with the quality behind the persona conjure up a bewildering sense of awe. Behind the glamour, though, lies the pragmatism of O’Neill himself.

NR: Of all the photographs you’ve taken over the years, is there one that stands out as a personal favourite?

Terry O’ Neill: I think it’s Sinatra on the Boardwalk (1968) – that was the first time I met Frank Sinatra. I already knew Ava [Gardner], and told her I was headed down to Miami to work with her ex-husband – she said, “I’ll write you a letter.” So I go down to Miami and I’m waiting for Sinatra to arrive. I look up and see these men approaching, and I started to take pictures. Sinatra and his guys came right up to me, and I nervously handed Frank the letter. He read it, looked and me and said to his boys, “it’s okay. He’s with us now.” And that was the start of a long working relationship I developed with him. He was a legend.

Do you ever look back critically on any of your photographs?

Oh, of course. Sometimes when I go into the office and I’m shown the negatives of my work, I’m surprised that I took so many pictures. At the time though, when I was working, I never looked back. I was always looking for the next job.

Are you always in control of the image you take, or are there incidences where the outcome is entirely accidental?

I think, except for a few, it’s all incidental. I love the work of photographer W. Eugene Smith, and so,

“I was inspired to take photos of what I saw on the street. Sometimes the best shots are the ones you are lucky to catch.”

Is there a certain characteristic you focus on, and like to draw out in your photos?

I wanted to capture the subject just a little off-guard. If not that, I’d try to find that specific moment that defines who they are. With the photo I took of Terence Stamp and Jean Shrimpton, for example, the assignment I was given was to capture the “face of the Sixties”. Theirs were the first two faces that popped into my mind. I decided to get in really close and crop it in, so you are just left with this intense stare.

How do you control the portrayal of ‘star power’ in your photos of high profile celebrities?

I was never really bothered by all of that. I started out at the same time that many celebrities did too – movie stars, and rock stars. There was only ever one time I was asked to leave, when shooting Steve McQueen. But I did sneak in a few shots beforehand!

In terms of the poses that your subjects adopt, are they agreed upon beforehand – or entirely natural?

I’ve done both. When I was asked to take photos of the newest Oscars Best Actress winner, I wanted to do something different. I didn’t want the big smile, holding up the award.

“I wanted to know what it looked like the morning after – when it all hits you that you’ve just won an Oscar, and your salary has just gone up by millions.”

I asked Faye [Dunaway] to meet me by the pool of the Beverly Hills Hotel at 6am. I was friends with the guy who ran the pool, and he snuck me in. I set it all up – the papers, the breakfast, the Oscar. And she sat there. Many people consider that photo to be one of the best images of Hollywood.

In the time since you started out, what is the most significant change to take place in terms of celebrity photography?

Selfies! And the fact that stars have too much control over their image now. In order to work with a celebrity, you have to deal with managers, publicists and the managers of the publicists, you have to give up approval and rights. By the time the photograph runs, it doesn’t even look like the person you shot! Everything has been approved by everyone – except for the photographer. In that sense,

“we’ve lost a lot; a lot of great pictures will never be seen, let alone even taken. It’s a shame. Everything is staged and then made to look better. It’s no longer just a great photo of someone.”

You’ve said there is nobody today that you’d want to photograph, what could change your mind on that?

I was very lucky that I worked at a time when stars like Frank Sinatra, Audrey Hepburn, Elizabeth Taylor, The Beatles, even David Bowie, were around. If you invented a time machine and send me back to the ‘60s, then I’d change my mind!

Credits

Terry O’Neill: Rare & Unseen is available now

Photos