“It’s this kind of interdisciplinary weaving together that is going to make change happen”

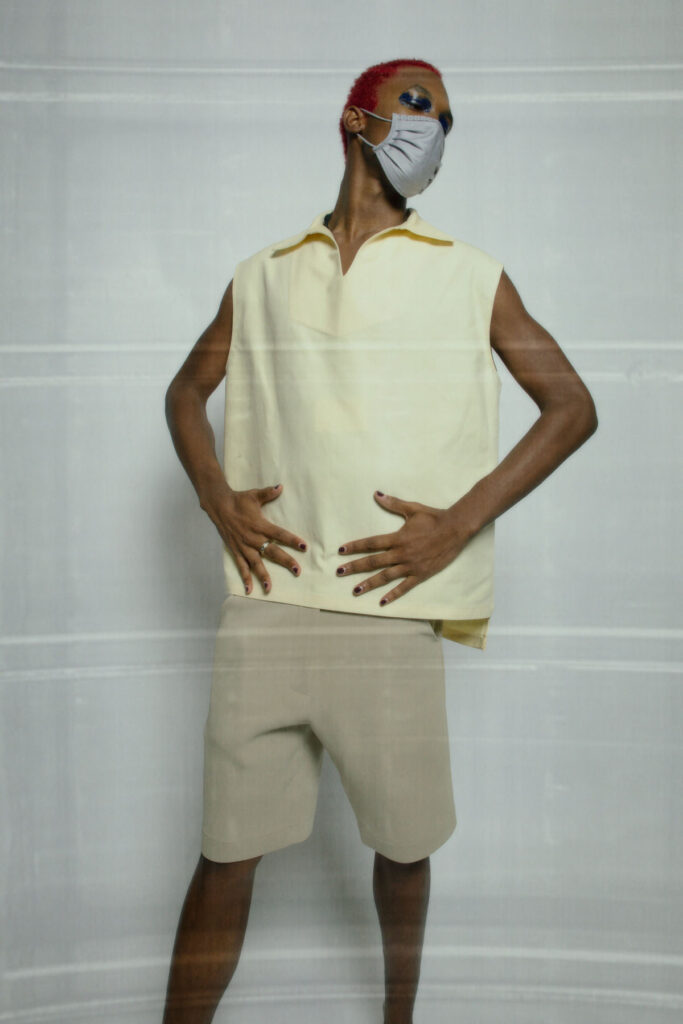

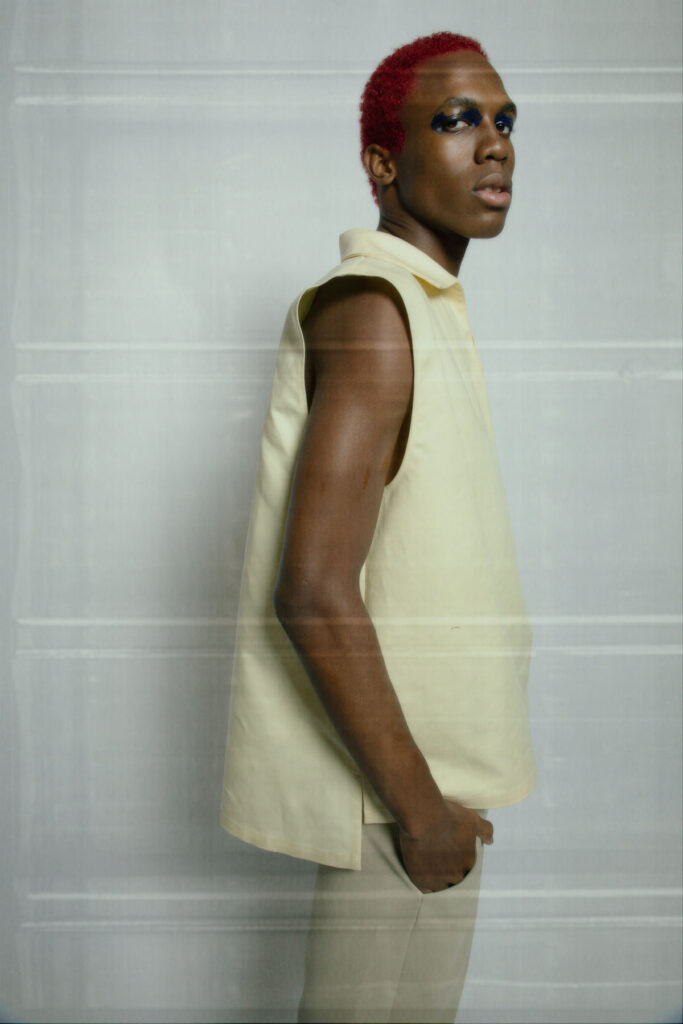

Founded in 2009, Practice Architecture is a London based firm adept at delivering various acclaimed cultural, community and residential projects. The firm has established itself as one that creates exceptional structures with a strong sense of place, and has a hands-on approach, getting involved from a design’s inception through to a structure’s completion, and help to curate both space and the activity it houses.

For their innovative Flat House project, the firm worked alongside hemp farmers and with sustainable methods of construction to construct a zero-carbon home in Cambridgeshire from prefabricated panels, all in just two days.

Their smaller scale Polyvalent Studio project was created within the parameters of the caravan act, meaning in most contexts it does not require planning permission. It was designed by students from London Metropolitan University and constructed within just 12 days, exemplifying the possibilities of low embodied energy design and the benefits of a collaborative working process in the industry.

Practice Architecture is currently working with food growing workers cooperative OrganicLea in developing a 10-year plan for the expansion of the infrastructure at their main site Hawkwood. The project will deliver substantial new educational buildings and volunteer spaces alongside a large community hall and kitchen, and the project will be built from natural materials as a self-build, working with the volunteers on site.

NR Magazine speaks with Practice Architecture to learn more about these projects, how they incorporate sustainable methods into their practice, and their ethos as a firm.

What inspired you to start working with cultural and community projects?

We started making things in London in a very informal way. We worked a lot with our peers and what we were doing was really part of a broader DIY culture within our community. In the absence of institutions that spoke to us, we made our own spaces in which to explore our own culture. This kind of work was only possible under the provision of it being temporary, but serendipitously, almost all the places we built in this era are still here.

We made our buildings in a very hands-on way, going on site ourselves, with friends and volunteers to build a project and used very basic tools and equipment to do so. This experience continues to feed into the work we do now, our understanding of materials and the way we design with others.

More designers are using hempcrete at the moment, and I’m familiar with artists using it on a small scale with pottery and sculpture, but nothing like on your Flat House project. What was the process like when building with this material on a larger scale?

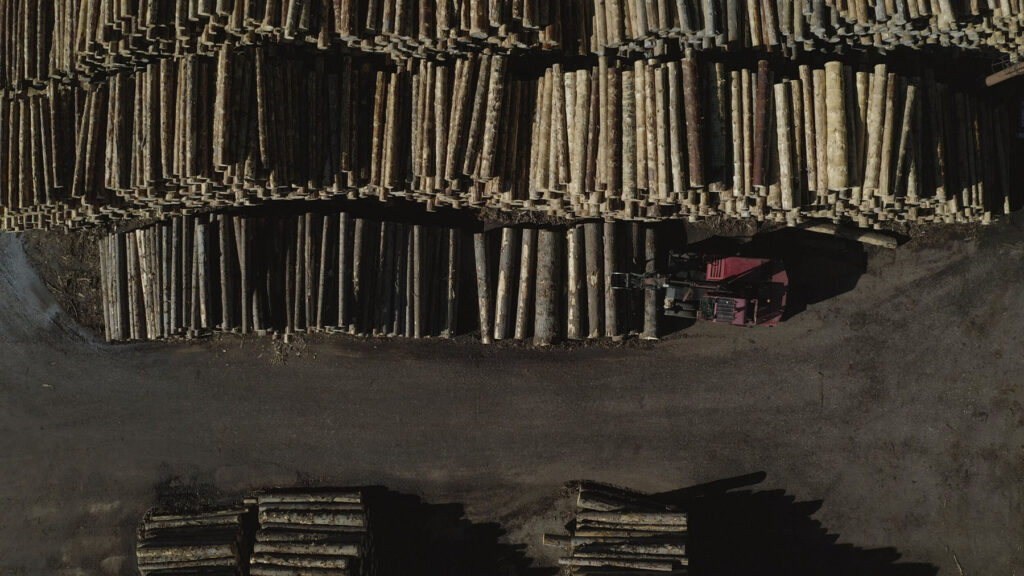

The process began with the drilling of the seeds in the 30 acres of field that surround the house. This was overseen by Joe Meghan, a hemp farmer who had supported Steve Baron the client and founder of Margent Farm in getting a licence and specifying the appropriate subspecies of plant.

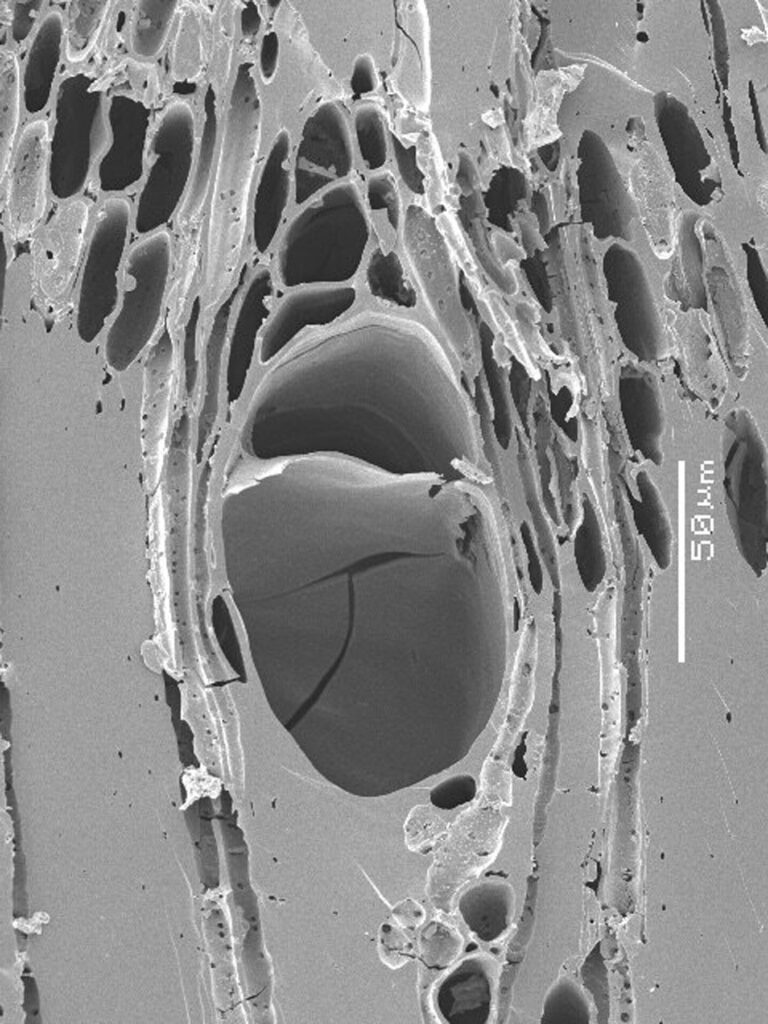

Hemp is a very resilient crop, with long tap roots that help to rehabilitate and condition soils that have been degraded through industrial farming practices. It has a short growing season of 3-4 months, after which we were able to harvest the seed and stem and process it into usable oil, fibre and shiv (the woody core of the stem).

The project makes use of each element of the plant, with the oil being used by Margent Farm in health and body treatments, the fibre being made into a cladding and the shiv into the hempcrete insulation. Each element of the plant went through a different process, with the fibre being felted and blended with a sugar resin and the shiv being chopped and mixed with a lime binder.

We designed a cassette-based construction system using structural timber with hempcrete to form an insulated panel, refining the construction details with Oscar Cooper from Lignin Builds. The panels were constructed in a factory and dried before being brought to site and lifted into place over two days. The cladding was made a few miles down the road with the impregnated hemp fibre matt pressed to form corrugations. The cladding is very easy to work with as it’s light and can be cut using a simple hand saw. We were lucky that with so many elements of experimentation, everything went very smoothly, and the building came together as anticipated.

Aside from sustainability, what were the other aims and inspirations behind your Flat House project?

We wanted to demonstrate how, what are often thought of as traditional materials, can be applied in a very contemporary way using the latest construction technology. The project celebrates the simplicity of its construction and how few materials went into making it. The key thing with Flat House was not just to develop a building, but to develop a whole system that could be replicated at scale across the country.

The project has led to the establishment of Material Cultures, a research organisation that explores natural materials in the context of offsite construction. Could you talk a bit more about that?

Yes, Material Cultures is now doing the work of scaling up these ideas and applying them to large scale housing and commercial projects. We are working with a variety of clients and housing developers – people who are interested in doing things differently. Alongside this, we carry out research projects with a number of universities, developing full scale mock-ups and looking at the broader cultural context of the work we do.

Material Cultures is exploring how regional specificity and a relationship to regenerative agriculture might shape the evolution of new housing typologies. The low carbon construction industry is still relatively embryonic, which means working across many fields and disciplines simultaneously to make things happen. That’s why we are really excited to be working with Yorkshire and the North East and ARUP to develop a regional strategy for a transition to a bio-based construction economy.

It’s this kind of interdisciplinary weaving together that is going to make change happen.

What does collaboration mean to you as an architecture firm?

For us architecture has always been as much about process as it is about built form. The design is material and construction led, which means really understanding how something is put together.

“Each project is an opportunity to connect with different disciplines and expertise, to learn and test something.”

We have been really lucky to have amazing long-term collaborators such as Henry Stringer – one of the most inventive makers of things – and Will Stanwix who has over 20 years’ experience of working intuitively with natural materials.

We generally make places directly with the people that use them, whether that be through getting everyone on site during the build or developing genuinely engaged co-design processes.

How do you go about balancing space and intimacy with a project?

We are really interested in spatial qualities and the different ways in which we are acted upon or made to feel by a building. We look to create balance, often pairing close and intimate spaces with more open ones. Material plays a large role in this. Arriving at the Straw Auditorium project in Bold Tendencies you move from the harsh open floor plates of the concrete carpark into an intimate womb like space, enveloped by the tactile warmth and smell of an organic material.

What inspired you to work with cellulose-based materials for the Polyvalent Studio project?

The Polyvalent Studio project was developed with David Grandorge and students at the London Metropolitan School of Architecture. The project was a continuation of Practice Architecture’s work exploring natural construction at Margent Farm and shares a lot of the material technology developed with Flat House.

The building is designed within the caravan act meaning it can be moved in two independent modules and that it could be built without planning permission. It touches very lightly on the ground with timber footings that penetrate the soil line. These are made from Accoya, an acetylated timber product that can far outperform other timbers and represents exciting opportunities for the substitution of traditionally high carbon materials in exposed areas.

The studio was designed and built by students at London Metropolitan School of Architecture. What was it like working with students and completing the project in such a short space of time?

Building the studio together with the students was a really amazing experience. They brought so much energy, passion, and commitment. It is mournfully rare for architecture students to get an opportunity to use their hands and build things at scale.

“Building things is one of the most direct ways to learn how to design things, and the lack of genuine understanding of construction by architects is what leads to many tensions between professions.”

This project was established within the context of your research into natural materials and low carbon construction techniques like with Flat House. What other kinds of innovative solutions to sustainable construction are you hoping to work with?

We are always looking to learn about new materials. Currently this means exploring innovative straw and mycelium construction and looking at the role of chalk within structural and civil engineering projects.

With the theme of this issue being Identity, I’d love to know how you feel the firm incorporates sustainability and education into its identity.

For a long time, sustainability was something we did by default, but we didn’t really talk about it or have a way of articulating what we were doing. We saw our work as predominantly socially driven and about process – and the architecture and materiality as a means to an end.

It’s been interesting over the last few years to begin redressing and articulating an underlying intentionality behind our approach to how things are made. Underlying the design is a deep concern for how the things we make fit within a broader cycle and ecology of things. Where do the components come from and where do they end up? How can we be resourceful and responsible? It’s been great to begin to articulate these things and situate what we have been doing within other conversations around things like regenerative agriculture and the logic of global supply chains.

How important is adaptability to you?

We want to make buildings that can respond to their users. This means they need to be able to adapt and evolve. You can design in a way that either makes this very difficult or enables it. By keeping structure exposed and close to the surface and making the construction legible, it empowers residents and users to add, change and adapt.

Working with a food growing cooperative, your Hawkwood Plant Nursery project also champions natural materials and community collaboration. Could you talk a bit more about the aims for this ten-year plan?

It’s really exciting to be working on a number of large-scale food growing projects in London. These kinds of spaces are so important and so different from other types of green spaces such as parks. They offer the opportunity for a genuine connection to soil and to land – one that is mutually nourishing and that brings you into contact with most important natural processes that we all depend on like the water cycle, photosynthesis, composting and soil formation.

Hawkwood and the other Market Garden City project Wolves Lane are leading the way in setting a precedent for socially and community focussed food spaces. We are looking to embed genuinely circular principles in the project, working with the resources available on site and integrating locally sourced natural materials wherever possible. The principal being that anything we are bringing onto the site can ultimately return to those natural cycles itself, in the form of mulch and compost.

Credits

Images · PRACTICE ARCHITECTURE

www.practicearchitecture.co.uk