“sometimes the planning is just a roadmap to set the initial building blocks for the society to evolve”

Science fiction is in at the moment. In October we’ll be trooping to the cinema to watch the film adaptation of the Dune saga, which is to sci-fi what Lord Of The Rings is to fantasy. The viral Ice Planet Barbarians Kindle novels, an epic romance series about blue alien boyfriends, has been picked up by Penguin Random House. Even on Netflix the new Korean drama Squid Game, which blends together horror and near dystopian sci-fi in a nail-bitingly binge-worthy package, is currently number one in the whole of the UK and worldwide. And in 2054 they are going to start building a sustainable city on Mars.

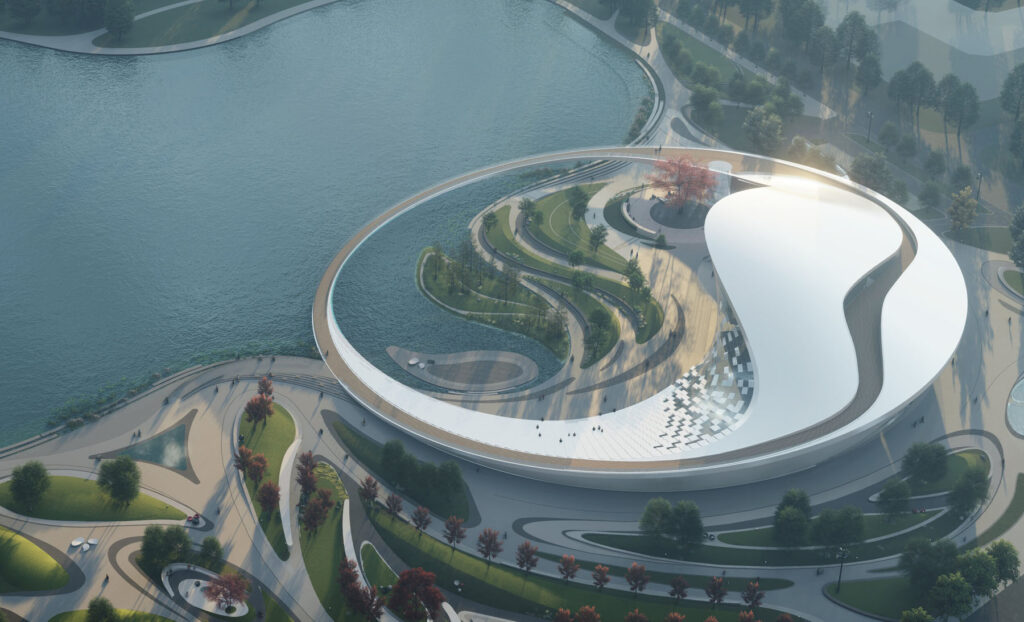

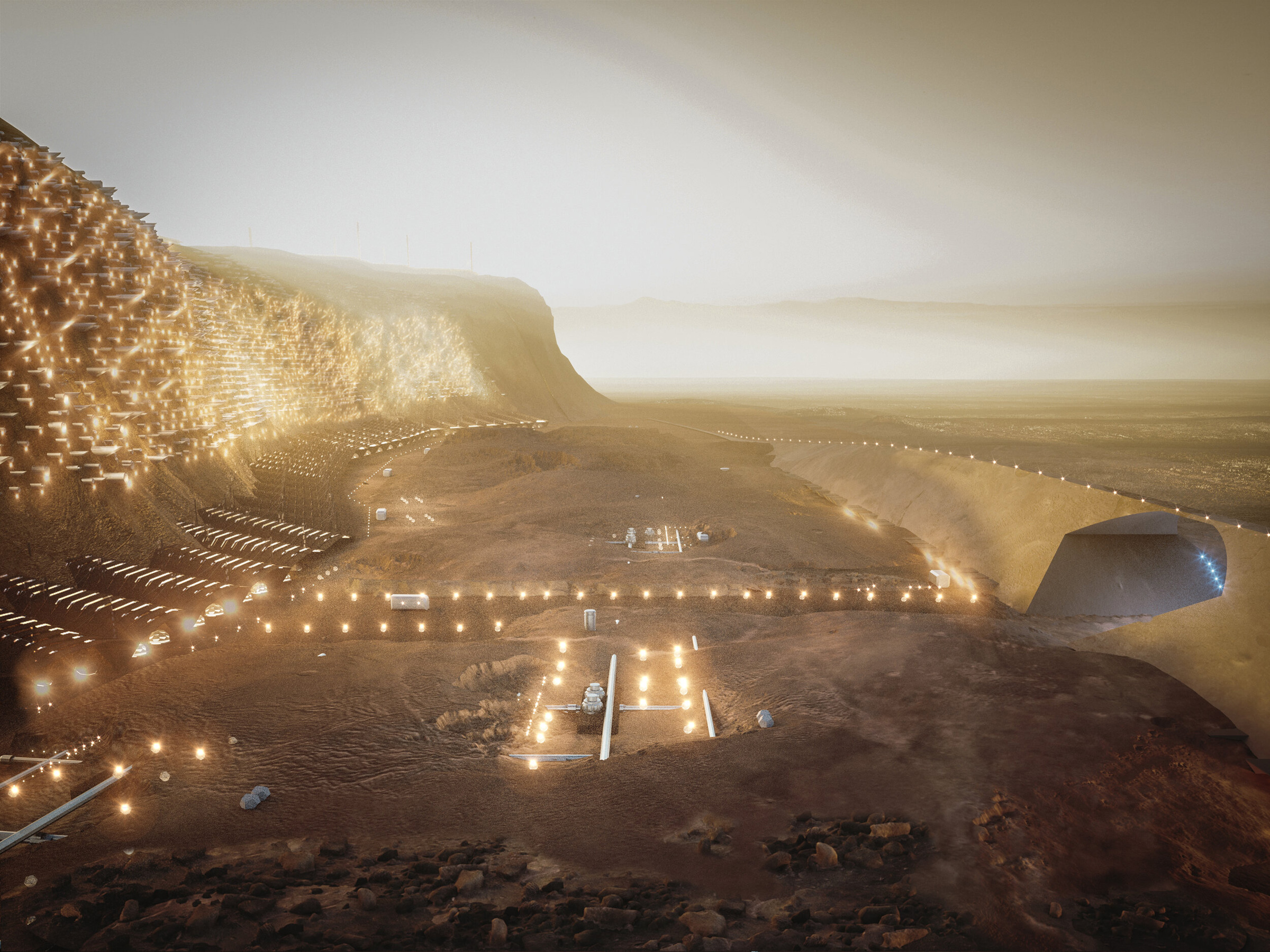

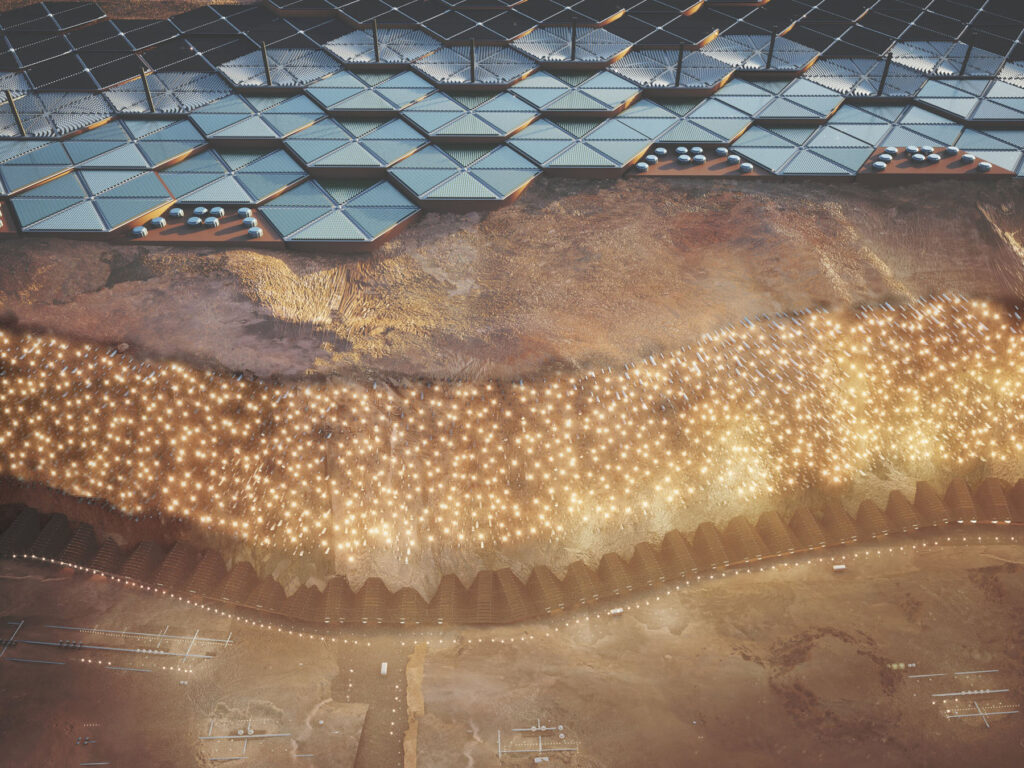

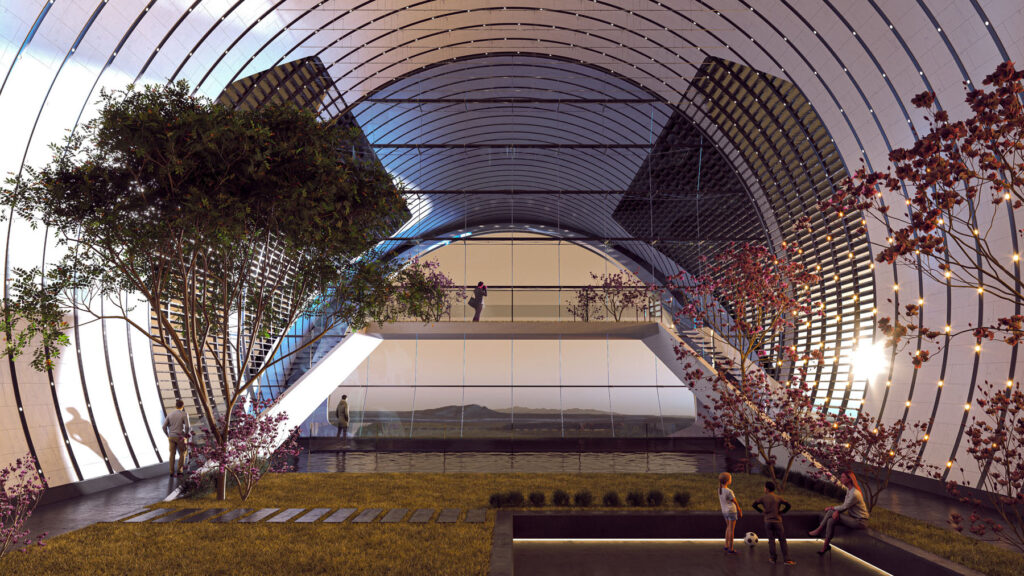

Oh wait, that one isn’t fiction, it’s actually going to happen. Or at least that’s the aim of ABIBOO Studios who have teamed up with SONet to design Nüwa, one of five cities proposed to be built on the red planet, with the first colonists set to arrive in 2100. Built into the slope of the Martian cliffs near Tempe Mensa, “the steep terrain offers the opportunity to create a vertical city inserted into the rock, protected from radiation and meteorites while having access to indirect sunlight.” The city will be connected via high-speed elevator systems, and everything from schools to farming to indoor parks will be available to the citizens. To get there you will need to spend one to three months on a shuttle and tickets will cost a whopping estimate of $300,000. No need to worry about the return fare though, once you arrive on Mars you will probably be there for good, so it’s certainly not a journey for the faint-hearted. NR Magazine joined ABIBOO founder and chief architect Alfredo Munoz in conversation.

Nüwa is an incredibly exciting project and it has been stated that the things that can be learned during the conception and creation of this city could be applied to issues on Earth. However, is there not a risk that these solutions will never actually be implemented on Earth, especially as there are already solutions to issues here that still haven’t been fully implemented such as renewable energy etc, and the majority of resources will be focused on the space race and cities like Nüwa?

So there’s obviously always a risk of the innovation not being implemented, but there is definitely the opportunity to implement it. And that’s where the learning that we can do by thinking out of the box and implementing it back on Earth is very valuable. Let me give you one very simple example. When we were working on the solution for finding the most efficient way to generate food on Mars, we developed hydroponics technology, which in concept is a technology that allows farming indoors. It’s highly efficient. It has been going on on Earth for a while, but recently it’s become quite common in the US.

It’s not possible to have an animal-based diet on Mars. The reason for that is that they require a lot of space, which obviously on Mars, it’s tricky because we cannot have them all outside in the environment. We need to treat that spaces where animals would be in a similar way that we would treat the spaces for humans, with the right pressure, the right oxygen. This is very expensive to build and very expensive to maintain. So it was not realistic to consider a diet based on animals. The team of life support experts proposed a solution that was mainly based on algae and insects.

When we analyse the area that we needed per person to farm the food that humans would need on Mars, we were talking about a little bit more than 100 meters per person. That means that in 100 meters per person, we were able to generate all the food that future Martians could need. Okay. Now, let’s look at Earth, on average, every person requires 6000 m² for farming. So if you compare a 6000 m² per person versus 100 m² per person, there’s a huge gap. That means that we could use more efficient technology for crops and for farming and we could reevaluate the type of diet that we have on Earth. It can liberate a lot of space on Earth where we can actually plant trees or nature. That could help a lot with climate change.

So, yes, there is always a chance that the technology that’s developed for space will not be implemented on Earth, but sooner or later, if it actually brings value, it will be implemented.

How do you think culture would potentially evolve within these cities on Mars and what might those new culture’s look like and involve?

So culture is very connected to how we live in the cities. One of the key aspects for us was to create a sense of identity, a sense of belonging. When we designed the city, we were very clear we were not designing a temporal settlement. We were aiming to create a city where people will go and live and die, and have families. So a sense of belonging and identity is critical, and that is part of what we think will drive local culture.

Another thing that I think is very important is the sense of community. So Mars is a very harsh environment. It’s not like Earth, where we change our environment as per our needs. On Mars, we will need to adapt to the environment. So that means that in such a harsh environment, we actually need to rely on each other much more than we do on Earth. On Earth, we used to rely on each other much more. Then as centuries passed and culture changed especially Western culture, we became much more individualistic. But we think that given the harsh environments on Mars, society will have to rely much more on their neighbours.

“We will need to look after our neighbours and our neighbours will need to look after us. If that trust is broken due to the harsh environment and challenging conditions on Mars, everyone might be at risk.”

That has a critical impact on how culture would be, because again, we ambition that culture must be more gregarious, where people will be not so focused on their own self, but also where the sense of community will be even higher than on Earth.

I imagine that there would have to be some kind of like a law enforcement system or some kind of punishment system. How would that work in such a small community to rely on each other?

Definitely, and that’s something very interesting that we still need to explore. We are currently at the state where we conceptualise the main ideas of the city. We are currently developing it from the architectural and engineering point of view, and the schedules that we are talking about are quite large. We might be able to start construction of the city on Mars by 2054, which is almost 35 years from now. So there is a lot of other analysis that needs to be done in conjunction with a multidisciplinary team of experts that might add some of those questions that you are asking.

There is always the risk of somebody not behaving properly and that has to be included in the way that the city functions in the same way that we are thinking about hospitals, the same way we are envisioning a location. It has to be considered what type of law will run on Mars. Maybe this is an organic process. Maybe the first settlers will have to find a way to organise things with some inspiration from some things that work on Earth. But then at some point, the society will have to be self-autonomous over there, and they will make their own decisions.

For this project there were included proposals for economic models, forms of government and dedication systems and the question was asked “Since we have the chance to start over, would life on mars be better than on earth?” However Nüwa will still retain many capitalist elements, “We envision a system that will combine the private sector – we’ll have our own economy and currency that will incentivise entrepreneurship”. Why not implement forms of true socialism or communism, as capitalism is already failing us here?

Sure, innovation will be critical. Settling on Mars will require levels of innovation that we are not even used here on from people on Earth. So we are not aiming for the city to have huge differences of wealth. Indeed, we do ambition that people might have more wealth than others, but not the extreme situation that we have here on Earth.

And when we look into the past at communism, humans find a way to look into their own personal interests without looking for the good of people. Right. I live in the US. I appreciate capitalism as a way to encourage innovation, and I think controlled capitalism is something that facilitates innovation. What is not good is that when you have monopolies that take over the market and new entrepreneurs cannot provide the innovation, that is not true capitalism. However, on Mars, we believe that intellectual property and an opportunity to generate value to society should be rewarded through recognition in society and through wealth among others.

But have you not considered creating a society that wouldn’t use money? Because then you would do away with the issues of some people having more and some people having less. Instead, you could come up with other ways to incentivise people to be innovative?

There are a lot of opportunities to continue exploring in this space. So again, we are architects and scientists, but it’s important for us to have people from different fields to add value to the project. We worked with a multidisciplinary group of experts that went from astrobiology, economy, life support systems, planetary design. So we have a very large amount of people, but that was only the first step, right. There will be a lot of opportunities to continue evolving so, going back to what we were talking about, it could be possible.

And definitely, there is something to investigate with that. But we don’t see, at least as of now, the harm of rewarding it through a certain level of wealth, because ambition is part of who we are as a species. We are the human species, wants to strive for a better life and wants to strive for a better thing for themselves and for their community. We ambition that Mars could be a great gateway for the scientific community to be recognised as they deserve. And that is connected again with innovation, connected to culture.

We’ve seen designs for Nüwa but there are also four other sister cities such as Abalos City which would be located at Mars’ north pole and Marineris City in one of the biggest canyons in the solar system. How might the designs of these cities differ from Nüwa?

Yeah, so we did not expand too much yet about the alternative cities but I’m going to explain first why there are many different cities. One is access to resources. In our case, we ambition self-sufficient, sustainable cities on Mars. That means that we are not relying on resources from Earth to operate or build a city, only in the very early phases. The rest will all be constructed from local resources on Mars. There are a lot of resources on Mars but they are in different locations. Therefore, we need to have a small set of settlements to be able to access those resources. Secondly, we must consider safety or resiliency. What happens if there is a problem, an emergency or something that is not expected in one city and everyone is in danger? We need to secure everyone and move them. Somewhere far enough away so they can be safe. And if you combine those two situations, we thought that to create a safe, long-lasting culture and colony on Mars, we needed to split it. And in this particular case, we split into five different cities.

We think that providing an open platform for creating identity is important as well, so different cities will have different cultures Some of them might be very different from each other, and that again connects to the sense of identity. Why do some people like London and others like New York because they are different, right? It’s not only about the culture of the people living there, but also the physical environment that makes room for that culture. It’s all interconnected. So we think that a successful permanent colony on Mars will be divided into different settlements, and all those settlements should have some type of unique identity

As life on Mars would require 10x more energy to support than on earth it has been stated that, even with the aid of technology, life there would involve an intense lifestyle and settlers could be contracted to spend 60-80% of their working lives contributing to the city. One cannot help be reminded of the song The Fine Print by Stupendium, which went viral during the pandemic, that talks about indentured servitude to corporations in space. As the price of a one-way ticket is estimated at $300k and would no doubt require a loan for the majority of people, what would prevent similar such issues from occurring in Nüwa?

So I’m not aware of the reference that you were mentioning. That $300,000 was a very quick estimate to premature to know what will it actually cost? That number was more of an academic level calculation based on today’s numbers. Is moving to Mars going to be easy or cheap? No, but you don’t need to go to Mars. If you don’t want to go to Mars, feel free not to go to Mars. Some people decide to move to very remote areas, and some people prefer to live in a nice, comfortable place in the Mediterranean, it’s is a personal choice, right? We can all choose what we want to do with our lives. So some people might be more inclined in going to Mars despite the harsh environments.

But it’s going to be an extremely tough life, probably not appropriate for most of the people that live on Earth. Those that want the sense of adventure, the sense of exploring a new frontier in what being human is, and to be pioneers in what is next for the human species. Those are the ones that might be willing to go to Mars and have a very tough life. Again, it’s not easy not only because of the amount of work that will be required.

So again, if somebody wants to go to Mars for a holiday, probably that person is not going to be welcomed by the community because that’s not a person who is going to contribute.

We do ambition again, that the city is owned by the people, not by corporations. Again, there is a lot of room for development on this, but we think it’s important for the citizens to own the city and to own the proceeds associated with potential trade that might happen in the city. Obviously, there would be a lot of trade going back and forth between Earth and Mars.

But yeah, it’s not going to be easy, or cheap, or safe. And it’s not going to be pleasant because the diet is going to change, and the environments that we are building, which we think is amazing and so spectacularly beautiful, but they’re different to what we are used to. We’re not going to see the ocean, or nature, or have the opportunity to walk around without the suit.

“It’s only for certain people in the same way that in the fifteenth century some people were willing to risk their lives to travel west. In America we had the opportunity to explore new frontiers, and that will be only for some people that want to do it.”

I’m curious because you said that if you don’t want to go to Mars you don’t have to. But historically speaking, a lot of settlers and pioneers were people who were forced to go. If you look at Australia, a lot of people who were settled there were often criminals. It was the same with America. So I wonder what kind of people you would imagine would settle on Mars?

In this particular case, we ambition more people with vision, people that have a strong sense of community, a high appreciation for science. Which, again, if you actually look into the background of astronauts, they usually have a very high appreciation for science and for exploration, for adding some contribution to the history of humankind.

But in that particular case of settlers in the past, it was always connected to commerce. If you look at the reason, maybe not in Australia, but in the America the main reason why people were willing to go was commerce. And that’s where we see there is some room for the private sector to add value not only to the scientific community, but also tourism and mining. So there are opportunities that will come, associated with commerce between Earth and Mars, that could support some people to go.

Could a city like Nüwa be built on earth and would it be a viable economically and environmentally sustainable alternative to cities we have at the moment?

Yeah, so some aspects could be implemented on Earth. One of the critical characteristics of Nüwa is that is in a vertical cliff. One of the reasons for it is to compensate for the pressure, because the pressure outside on Mars is very low but we wouldn’t need to do that on Earth. Radiation protection is also very important, but here on Earth, we don’t have that problem.

The magnetism on Earth protects us from that radiation. But we see problems with climate change, with temperature rising. In some areas, the temperature is becoming so high and that’s going to continue to increase, so living on the surface might become very complicated in the future. So we do see some room to implement some of the solutions that we will implement on Mars. In that case, as of now, we are working on building a small version of the solutions on Mars in extreme environments on Earth.

So you build a small building in order to learn from it, to adapt, and change things as needed in order to be able to modify whatever is required. So you can continue improving the solution. So that is something we are currently working on. So we ambition building some parts of the Nüwa city here as a way to achieve an additional level of research and development. Also with the possibility of adding tourism, the scientific community could come and start experiencing on a very small scale how society could operate on Mars.

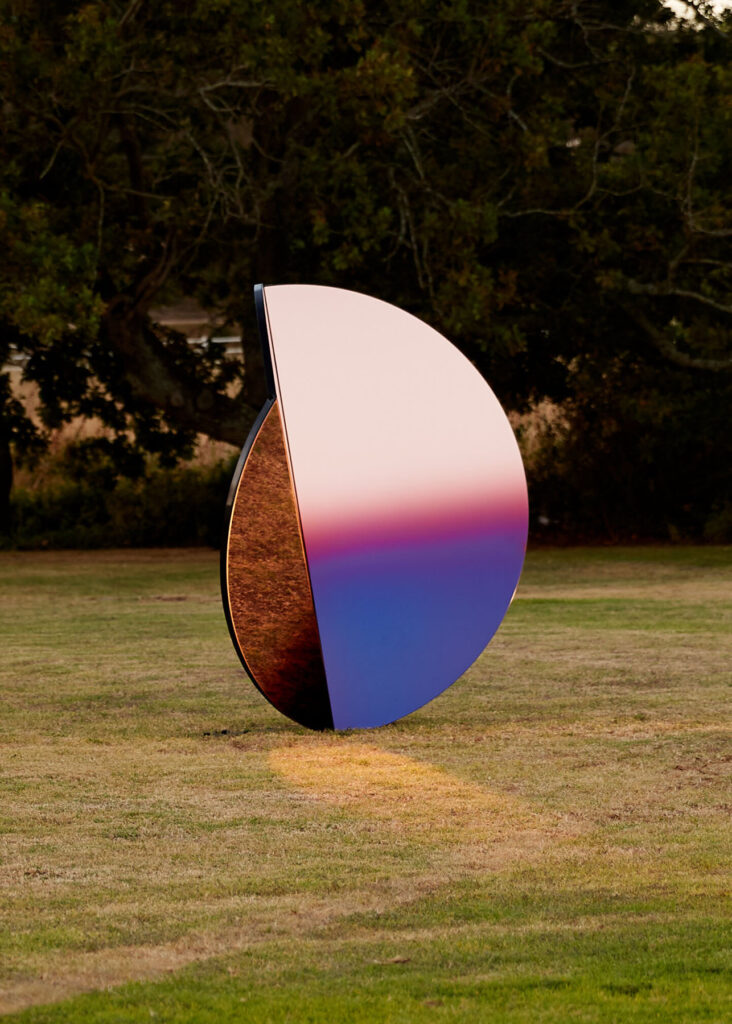

The interior living spaces are obviously quite uniform and modern in design. However, it has also been mentioned that maintaining the good mental health of the people within these cities is imperative. As humans find expressing individuality important would there be scope to customise their living spaces or would that require too many resources? The same goes for fashion and other things like that?

Definitely, that’s a very important point. And we are currently working on that aspect. We do ambition customisation. That is very important again, to the sense of identity. We want to feel a sense of belonging, but we also want to feel that we are not one among many. We have our own personal taste that has to be respected.

Similar to how we do co-living here on Earth or when you go to a dorm. You have private areas that are small, but you can customise a lot in your own space. Then all the common areas are public where you incentivise the social aspect of the community and where you have much more space to enjoy than in your private space.

Also with fashion, we are now working on the next round of designs where we are thinking about how fashion could be. If you wait a few months, you will have more opportunities to see how things are coming together.

What other ways do you think people will be able to express their identities within the cities?

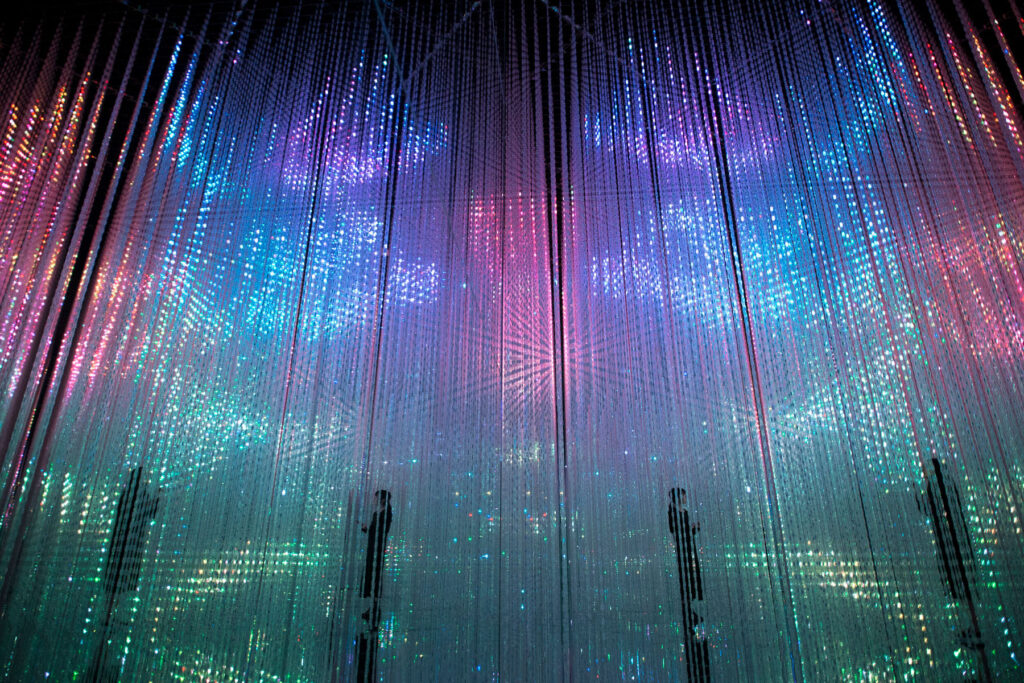

Arts. We are giving a lot of importance to that. We think that self-expression will be an essential aspect of society on Mars. Again, the advantage here is that Mars is not going to be in isolation. It takes 20 minutes to communicate between Earth and Mars, so there will be a lot of communication and interaction between the Martians and the people living on Earth. Right. So there will be a lot of room for again transfer of ideas because life on Mars will be so different, people on Earth can learn a lot from the experiences that Martians will have.

The use of AI and robotic technology will be integral to life on Mars, however, have you considered how people’s relationships with AI and robots might have changed in the future and how that might affect cities like Nüwa?

Definitely. We are working a lot on the next wave. I was telling you that in a few months you will be able to see the next round of exciting solutions for colonies on Mars that we are working on. And this question that you are raising is very connected to that.

“We see that AI and robotics will be essential for the survival of Mars, and therefore the relationship with humans will evolve. To consider robots not so much as tools, but as an emotional beings that we relate to.”

In Japan is very common that they don’t see robots as objects as we do in the West but instead see a type of soul associated with the robots. And we envision that not only on Mars, but in the near future. The relationship between artificial intelligence and humans is going to evolve or transcend from a pure tool to an emotional connection. I mean, the movie Her is a fun example. As we will not be able to have many animals on Mars robots could become the next type of pet where we have a very close emotional attachment.

I imagine because it’s like such a harsh environment, having that companionship would be essential for the good mental health of the people there.

Definitely. We think that the tools that robots will provide will not only be rational, they can also be emotional. And the communication with Earth as well. Again, remember that we are talking about the hyper-connectivity among the citizens on Mars and with the citizens on Earth as well.

Do you envision people being able to control the robot from different cities as a sort of way of online dating?

That’s again is something we might need to see what happens organically. Sometimes we can’t plan. As architects, we are good at planning, but sometimes the planning is just a roadmap to set the initial building blocks for the society to evolve. The local architects, the local politicians, the local engineers and the local artist will have to find their own way to live. That’s the beautiful part, right? To leave it so open. That allows for innovation locally. And that rounds up our conversation about how important innovation is going to be for the future Martians.

Credits

Images · ABIBOO STUDIO

https://abiboo.com/