«Too much analyzation can kill the work, there has to be some mystique and some danger or risk you take along the way»

An old glasshouse stands but continues to shatter as the wind runs through it. From its corroding rafters hang hair-like strands of organic matter, draped in entangled troughs that no longer grow but choose to speak in muffled rustles, envious of the birds that idle overhead, they are filled with longing. They are like exposed roots, barefaced and all out of tears, they sway in the breeze and pretend that they are flying. Gravity hums, its vibrations oscillate between remembering and forgetting what it is to be defied.

The Glasshouse sits at the edge of each of our individual ideals. Sometimes waves crash beneath it and within its walls we are surrounded but not safe. Others remark at its fragility but when I reach out to touch it and slide my palms down the old wood, I say that it is strong. I wrap my arms around myself and say that it will hold me like you used to, pulling at my shoulders for a tighter embrace. Defiance doesn’t always look like a lie. I learned to protect myself from within these walls, I tell you that I trust you but speak through them. I want to build a home with you but I don’t know how to leave this house without burning it down.

These sentiments are presumed, coaxed out of my subconscious as I press “Play” on a video that displays the work,

Glasshouse created a decade ago by the Icelandic artist, Sigurdur Gudjonsson. I was watching a screen, from my computer screen, with no tangible distance between perception and reality. This is Sigurdur’s strength. As the recipient of the 2018 Icelandic Art Prize as Visual Artist of the Year for his 2017 exhibition, Inlight, and the selected artist who will represent Iceland at the 59th Venice Biennale to be held in 2022, Sigurdur is a master of the senses. Utilizing moving imagery, synchronized soundscapes and installation, the viewer is dropped into an emotional fragment, engineered through layers and loops that create an immersive world numbed by specificity where feeling is not a derivative of direct experience. Having installed his projections in locations like morgues and churches, Sigurdur first sets the scene by taking the viewer out of his or her respectively normal settings and then transports them into his projections where the metaphysical becomes an invitation to surrender. Whether it is the innards of the Glasshouse, a lone pillar erect in the sea, or an electron-microscope’s magnification of carbon, the contours of these incongruous visuals become hyper-narratives that the viewer projects meaning onto as if reaching to reclaim a shard of something broken and without genesis, like a memory evading recall.

The footnotes of our innermost psyche are lured to the fore as viewers ascribe meaning to Sigurdur’s often poetically abstract works.

You’ve said about yourself that you’re often “quick to come home” when you find yourself abroad, what does home mean to you and how has it shaped your work?

I have been lucky enough to both travel, live, study, and work abroad and that has been very important for me. I currently live in Iceland so you could say that it is my home now, although I might choose to live elsewhere temporarily later. There has always been fascinating energy in the Icelandic art scene which has always fascinated and inspired me, both in visual arts and music and I think I can say that it has shaped my works in many ways. However, I think it’s incredibly healthy for every artist to stay abroad for some time and broaden their perspective and build new relationships. This is something I try to do every year, whether it be in connection to working or exhibiting.

What does Iceland provide that has made it a place that you have decided to stay and find success in your work?

Reykjavík is a small city when it comes to population and you are quite close to the sea with a view over to the mountains, it’s also only a short drive into the wilderness which I count as a blessing. I guess you always take some inspiration from the environment and the people you meet on the way and all of it somehow weasels its way into the subconscious, which I guess must be reflected in the works I make. At the moment, Iceland suits me well as I am focusing on a large-scale project for the Venice Bienniale in 2022. I work with a great gallery here in Reykjavík named BERG Contemporary and I have a nice studio close to where I live with my family.

How were you and your community in Iceland affected by COVID19? In a place like New York for instance I think it really altered the ways in which we were actually connecting with people. We’re always moving at lightspeed, often with a set of priorities that aren’t our own and it was a way to be forced into introspection.

COVID19 has been handled quite well over here. In March almost everyone stayed mainly at home for a few weeks and then we managed to get rid of COVID19 during a large part of the summer so people could enjoy each other’s company without worrying too much for a while. But now we are facing the third outbreak over here and I really hope for an international solution soon. If we look at Iceland specifically it has been affected by so many things, apart from the obvious and most serious effect on those that became ill. Iceland has been a popular destination for travelers over the past few years, so the travel industry is struggling. Theatres just opened again for the first time since March, but there are only half or one-third of the usual numbers allowed into the auditorium. Musicians haven’t been performing and of course, art exhibitions have been postponed as well. But I am lucky as I’m working in my studio all day at the moment so it doesn’t affect my everyday life too much at the time being.

The perceptive experience is an anchor in your work where emotional fragments can be strung together to mirror something whole in its potential for universality. What do you want people to experience when they come across your work? Is the desired result always a certain emotional response and do you want that response to be singular?

I’m interested in creating a surrounding experience for people, multiple layers of perception, a world you can immerse yourself in, not only an emotional one; it can also be strong visually or physically and hopefully it moves something within the audience.

It’s interesting because we all experience life as individuals, but when you put us in this context where the individual is surrounded, their perception is controlled in a way that almost forces them to confront something more subconscious. Are the frames you build mirrors for humanity almost?

I hope so. That would be amazing. I guess it’s easier for an outside viewer or audience to answer these questions, it’s rather difficult to know what impact one’s work has on others.

For me, it’s created from within but often also it’s a way to express what my eyes have caught when I walk through life.

So my work stems from an inner drive and sometimes a need to put focus on things that have caught my attention, which can be anything from machinery, man-made construction, or technical relics for instance. I hope that the audience experiences their read of the different layers of the narrative within each piece and that the whole space comes together simultaneously, combining different elements

You use the word narrative, do you consider yourself a storyteller?

No, I think I’m always trying to hide the story.

In what way?

I like it when a narrative becomes more of an undercurrent.

You mean it’s something that you want your viewers to bring out of themselves to fill the piece?

Exactly. It’s always a pleasure when that happens. Perhaps we could say hyper-narrative.

The creation of a narrative through perception is interesting. You often work with musical composers and sometimes there are inherent narratives present within sound, especially when things are instrumental and there are no lyrics to guide you in terms of emotionality. Where do you find those nuances?

When I’m in the process of doing work, it’s sometimes a very unspoken process because it’s not a specific path that I’m following. It’s almost like wandering around until I feel that I have reached an area of interest. Then I start to make different implementations and play around with it. This process is sometimes like tuning an old radio back and forth until you catch the frequency you like.

Normally I think we assume that the ways of working are like, okay here’s a video and we need to engineer a sound for it, but how is it working in the inverse, like making videos for sound? What is the dialogue that you’re having, not only with yourself, but with the other artists that you’re collaborating with?

It’s a different process with different artists.

Like with Anna Thorvaldsdottir, a composer I worked with on my latest work, Enigma, it’s a very intuitive process. We almost don’t have to speak. I know her quite well and she knows my aesthetic, and vice versa and the outcome is somehow always interesting. We throw ideas back and forth for a while and then they start to take form.

A lot of your work is time-based and in tandem, it seems that the relationships you’re cultivating with your collaborators also work on this scale. Do you feel like the collaborations themselves are also like time-based projects?

In a way, yes. Some of these projects are unique and created in the moment, while others have evolved further and manifested themselves into longer partnerships. But it can be said that the works themselves take care of how they develop, whether they grow or not. If that happens, it’s always a pleasure.

Right and inherently there is a level of intuition that comes with relationships that allows for a deeper level of empathy and perceptiveness that becomes activated through collaboration. What do you think is the connection between creativity and intuition and to what extent are both tools for society?

I think the process of all artists is a combination of intuition and knowledge and it is important to trust it and follow it.

When I look at a piece, the experience engendered seems quite universal and that’s a rare thing because it signifies that you as the artist, have been able to trigger someone’s emotional response without knowing anything about their experiences or their personal narrative. It’s like the work is looking outwards somehow and sees us individually, is this your intent?

Thank you. Those are big words. My answer is maybe.

How do you know when a work is completed per se? Is it because you feel a certain way after you look at it or how do you know?

You never know. It’s usually defined by the moment when the piece goes away, you have to stop at one point. I like when the piece gains its own life somehow and starts to grow inside a space; when it becomes possible to play with the video in a performative way where its surroundings activate the video somehow and the reading of the work becomes completely different due to its placement.

Locations are so interesting for you. You’ve done exhibitions in a morgue and church and when you take your pieces out of these settings and into a museum for instance, how do you think that changes the piece? Is its intent or means of communication ever impacted in a negative way?

I am very inspired by the space I work in each time. So very often the environment influences my work.

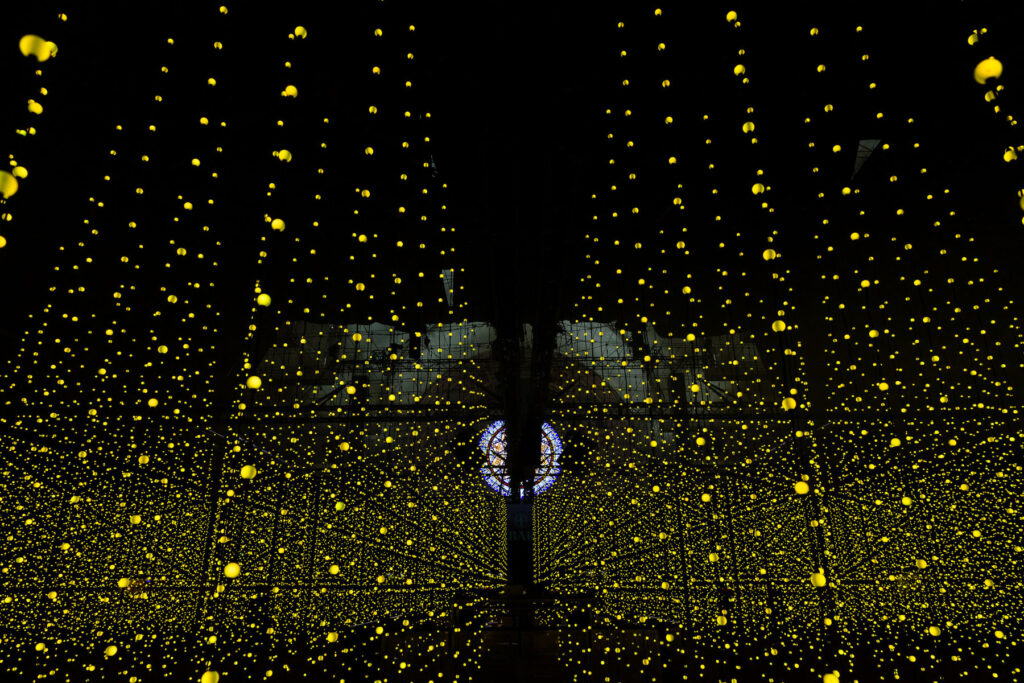

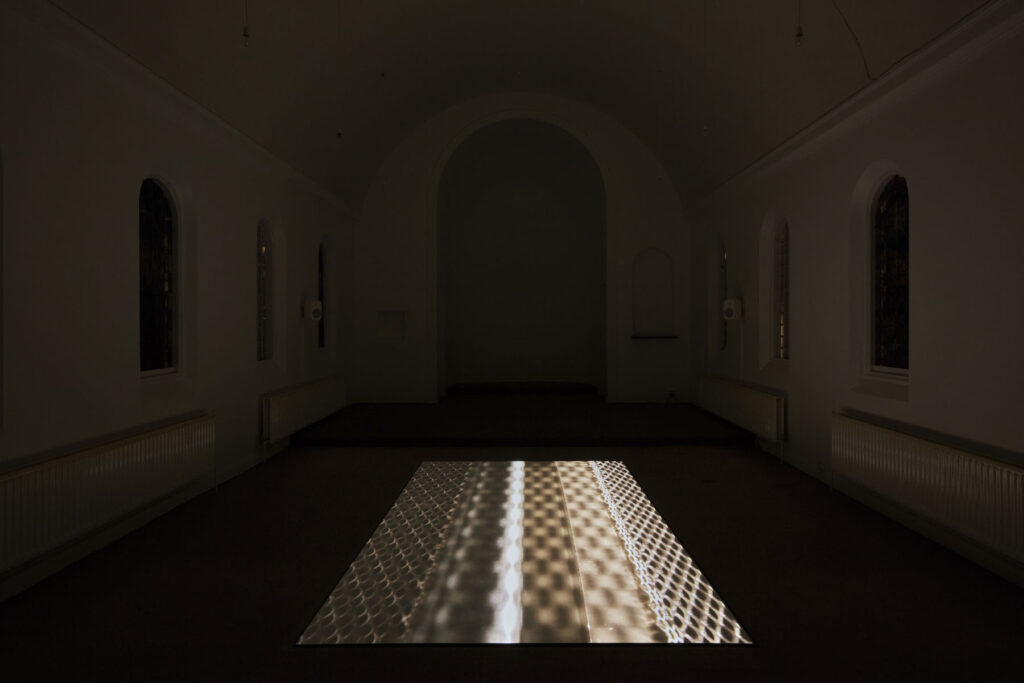

Fuser was deeply influenced by the old chapel in Hafnarfjörður which I found when I worked a project for ASÍ Art Museum in Iceland and later the work was also screened in an old barn in a farm in the North of Iceland. Even though it was created in a chapel it works well within a gallery, so that’s not to say that even if a work can be created and inspired from a house or a raw space, there’s always a new layer that is added to it when it enters a gallery or even a museum.

Do you think you lose anything though when you take it into the museum space or a space other than what you created a piece in?

It can happen, but at the same time the focus on the work can become clearer, which sometimes makes it better.

Do you think a work should always be malleable? You’re actively having to change a piece that you thought was “complete” so is that exciting for you as an artist to have to rethink something that you thought was finished?

No, I don’t really change pieces after they ́ve been performed unless it ́s another score that I write for it. It can be interesting to reflect on an exhibition in two different locations and reshape it.

Do you consider your work to be accessible? Is this something that is important to you?

It’s hard for me to say. I’m rather in search of nuance or something that clicks rather than thinking too much about what happens when the work is ready. I guess it would be risky to think too much about how people receive the work. For me, it’s about taking on the journey of creating the piece and challenging myself in the process. It has to be risky somehow otherwise it would be boring. You have to take a risk and make the most of the ride, the rest is up to the receiver.

We think that people exist outside of their work as if it could be separated, but for you, do you think your work is a reflection of your inner psyche?

I guess it’s influenced by what I see and explore and what I choose to show to others and in that way, it’s very much so related to who I am. Some videos I create from images that I have imagined or an idea that comes from within but in other cases, I choose to show to others what has caught my attention. I guess art can have its own soul or psyche as well. It becomes its own character. My work is fuelled by my inner psyche without me being able to explain that further or analyze it. I’m not aware of how. Too much analyzation can kill the work, there has to be some mystique and some danger or risk you take along the way.

How does your work make you feel? How has it changed who you are?

I ́ve never thought about that. It’s more about expressing an idea in my mind and finding the right form for it. I tend to be thinking and focusing on the next project rather than dwelling on the ones that have already been produced.

The names of your pieces are rather poetic. Ranging from the idea of a veil, connection, even a deathbed, are your titles meant to guide the viewer?

For me, the title is always a kind of trigger that possibly poetically expands the work.

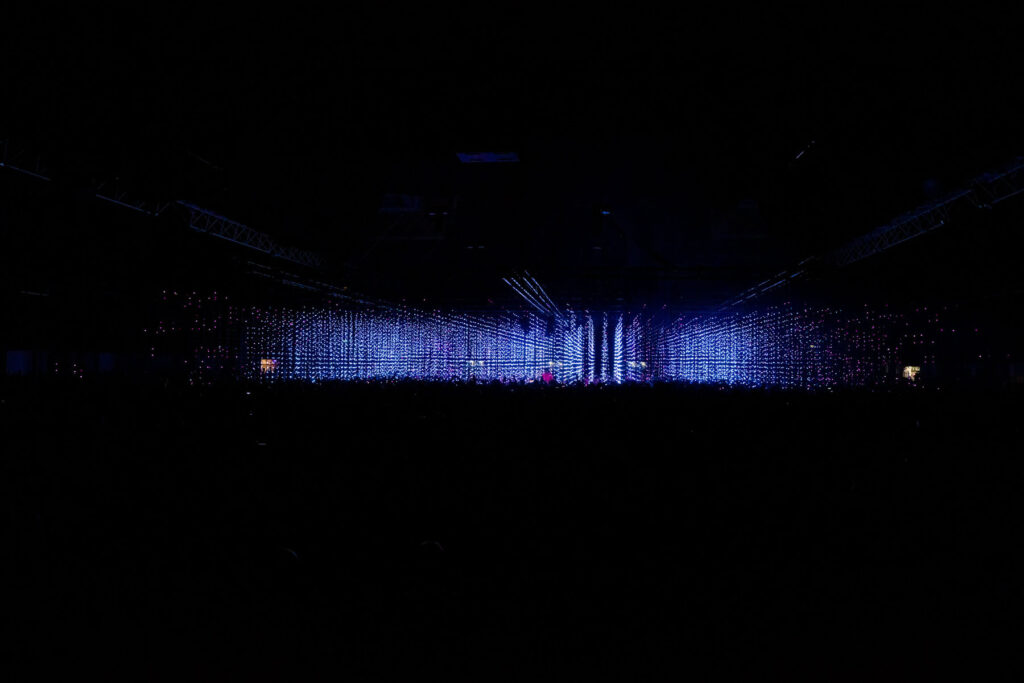

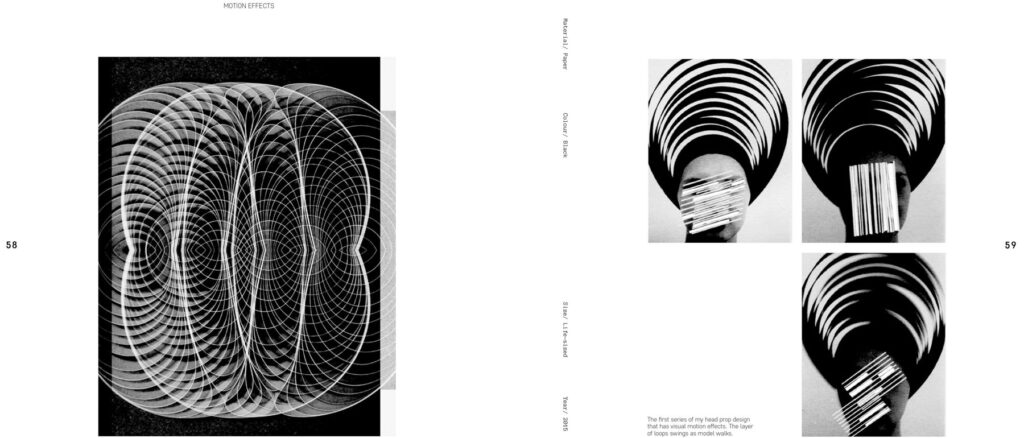

Sigurður Guðjónsson is an Icelandic visual artist based in Reykjavík. Working with moving imagery and installations, his works carry carefully constructed synchronized soundscapes, and provide organic synergy between sound, vision, and space. His works often investigate man-made construction, machinery and the infrastructure of technical relics, in conjunction with natural elements, set within the form of complex loops and rhythmic schemes. His all-immersive multi-faceted compositions allow for the viewer to be engaged in a synaesthetic experience, that seems to extend one’s perceptual experience beyond new measures. Sigurður has often collaborated with musical composers, resulting in intricate work, allowing the visual compositions, to enchantingly merge with the musical ones in a single rhythmic and tonal whole. His newest work, Enigma (2019), is produced in partnership with Anna Thorvaldsdottir (composer) and comprises of a string quartet and video. Created for an immersive, full-dome theatre experience, Guðjonsson broadens a fragment seen through an electron microscope into an extensive 360-degree video, exploring scale, perception and the poetic notions of the-in-between. Recently on tour with four-time Grammy nominees, TheSpektralQuartet, it is due to be presented at The Adler Planetarium, IL, Carnegie Hall, NY, Kennedy Center, DC, The Reykjavík Arts Festival and among other exhibition places in 2020. In 2019, it was announced that Guðjónsson had been selected to represent Iceland at the 59th Venice Bienniale, to be held in 2022. The artist was awarded the 2018 Icelandic Art Prize as Visual Artist of the Year for his 2017 exhibition Inlight, which featured video installations set within the defunct St. Joseph’s Hospital in Hafnarfjörður, Iceland and commissioned by Listasafn ASÍ. His work has been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions around the world, in such institutions as the National Gallery ofIceland, Reykjavik Art Museum, Scandinavia House, New York, BERG Contemporary, Frankfurter Kunstverein, Germany, Arario Gallery, Beijing, Liverpool Biennial, Tromsø Center for Contemporary Art, Norway, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, and Bergen Kunsthall Norway.

Credits

www.instagram.com/sigurdur_gudjonsson

www.sigurdurgudjonsson.net

Photos

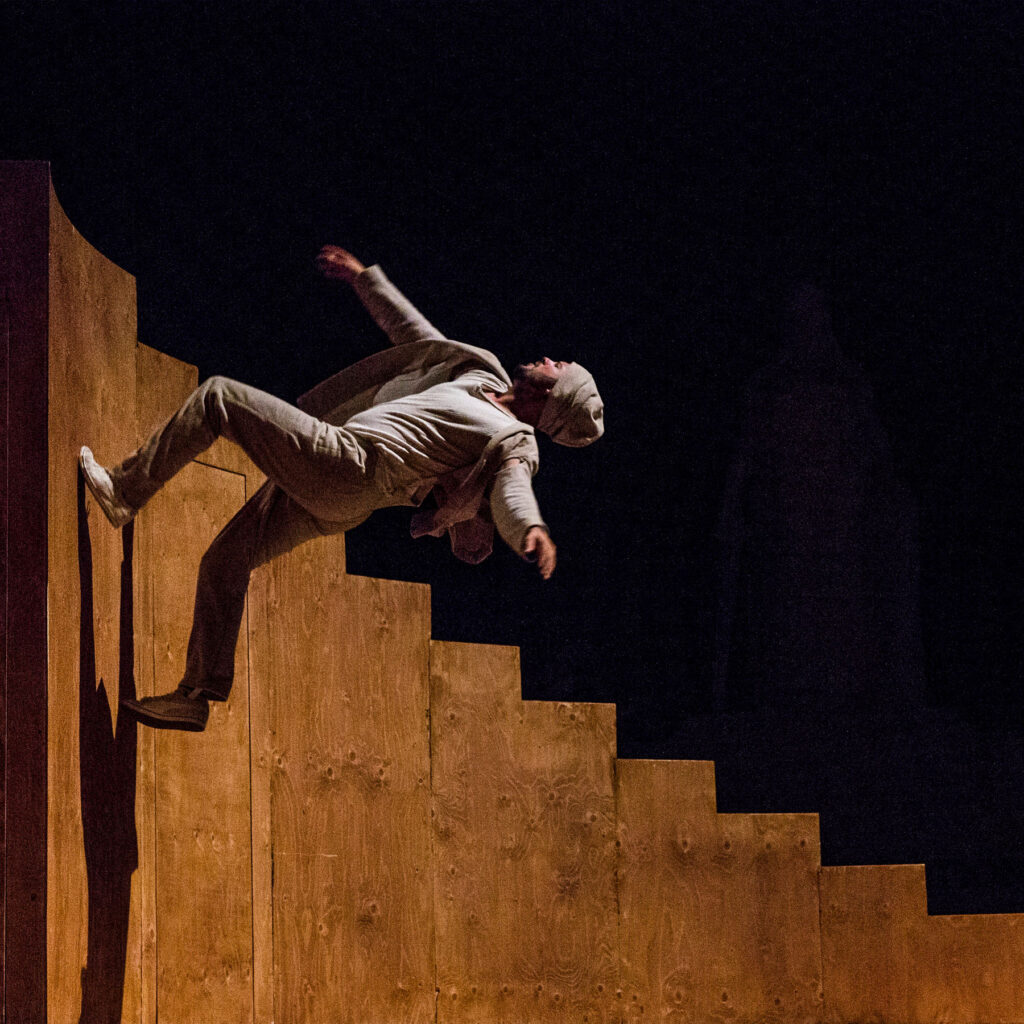

- Enigma, 2019 4k video, 27 minutes 49 secondsImage courtesy of the artist and BERG Contemporary

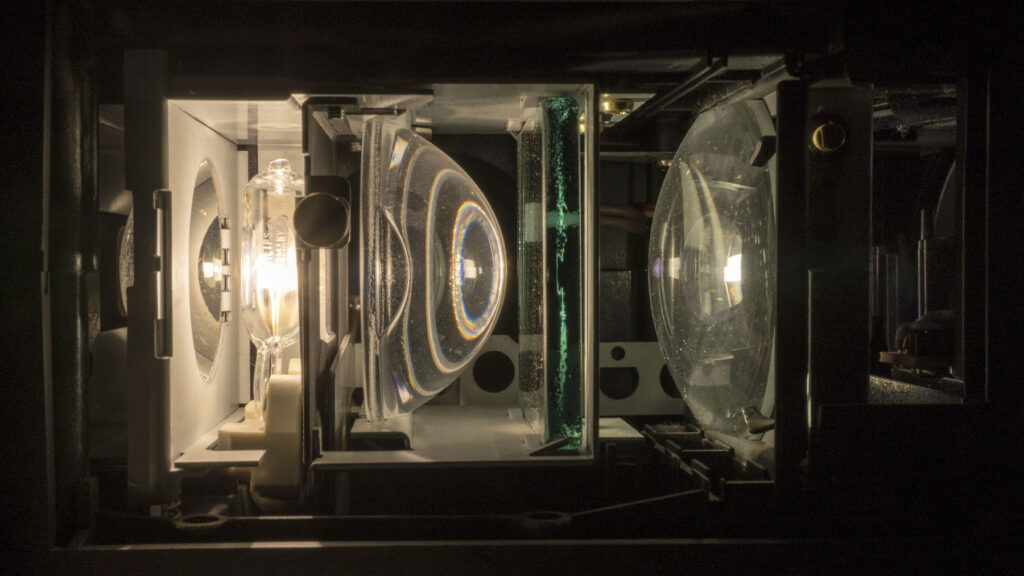

- Lightroom, 2018 HD video, stereo sound, 9 minutes 27 second Image courtesy of the artist and BERG Contemporary

- Mirror Projector, 2017 HD video, stereo sound, 16 minutes 10 secondsImage courtesy of the artist and BERG Contemporary

- Scanner, 2017 HD video, stereo sound, 40 minutesInstallation view: ASI Art Museum, exhibition in the outbuildings of Kleifar farm, Iceland Image courtesy of the artist and BERG Contemporary

- Fuser, 2017HD video, stereo sound, 38 minutes 45 seconds Installation view: ASI Art Museum, exhibition in the chapel and morgue of the former St. Joseph’s Hospital in Hafnarfjörður Image courtesy of the artist and BERG Contemporary