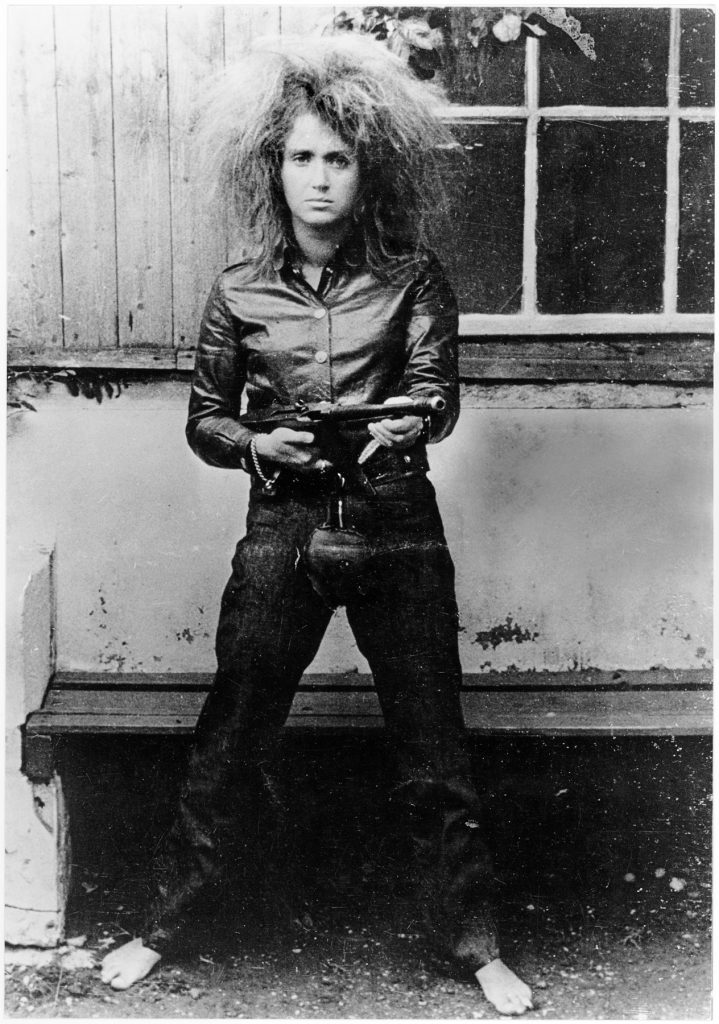

“whenever there is a human, I approach them as if they were a sculpture. And whenever there is an object, I approach it as if it was living.”

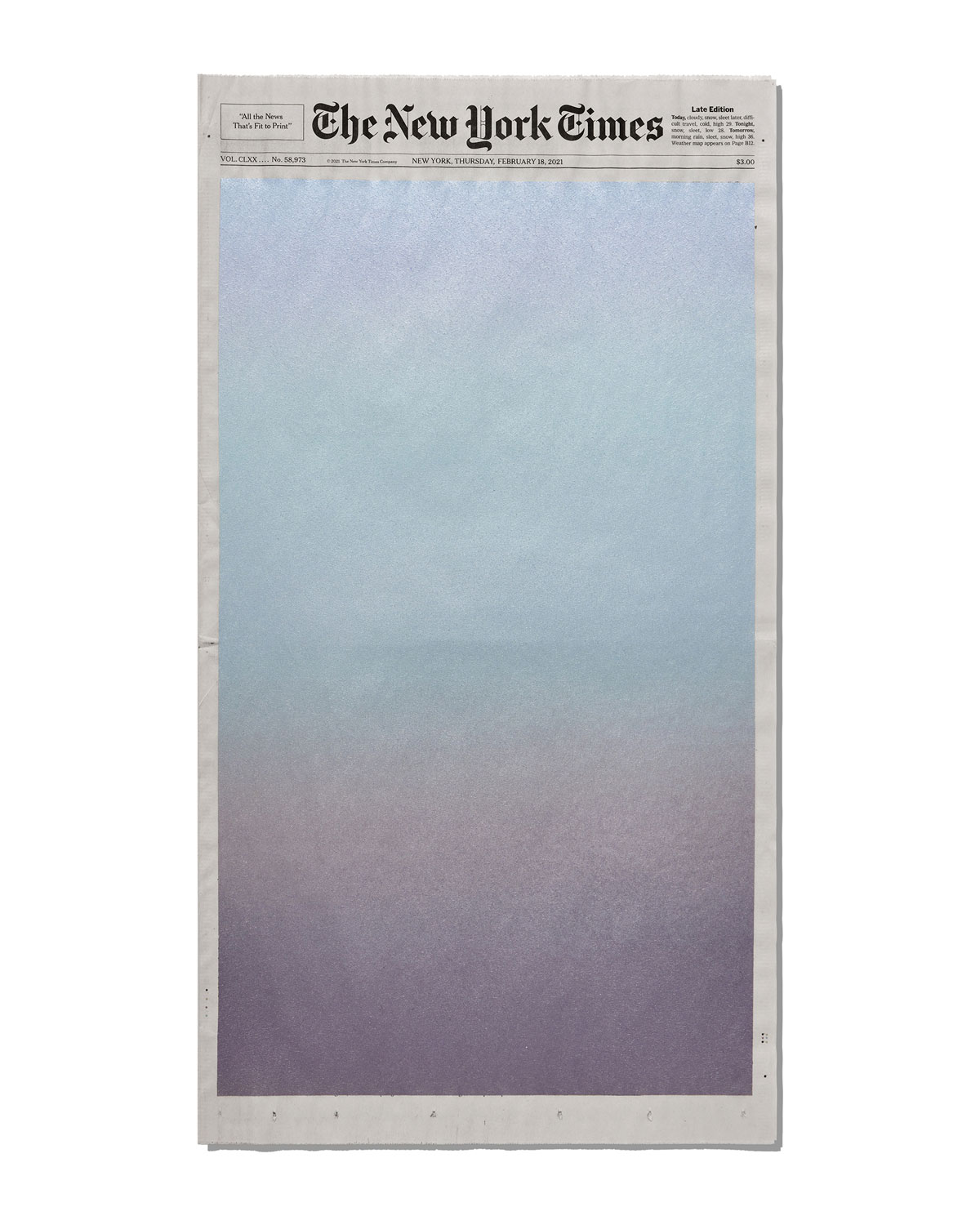

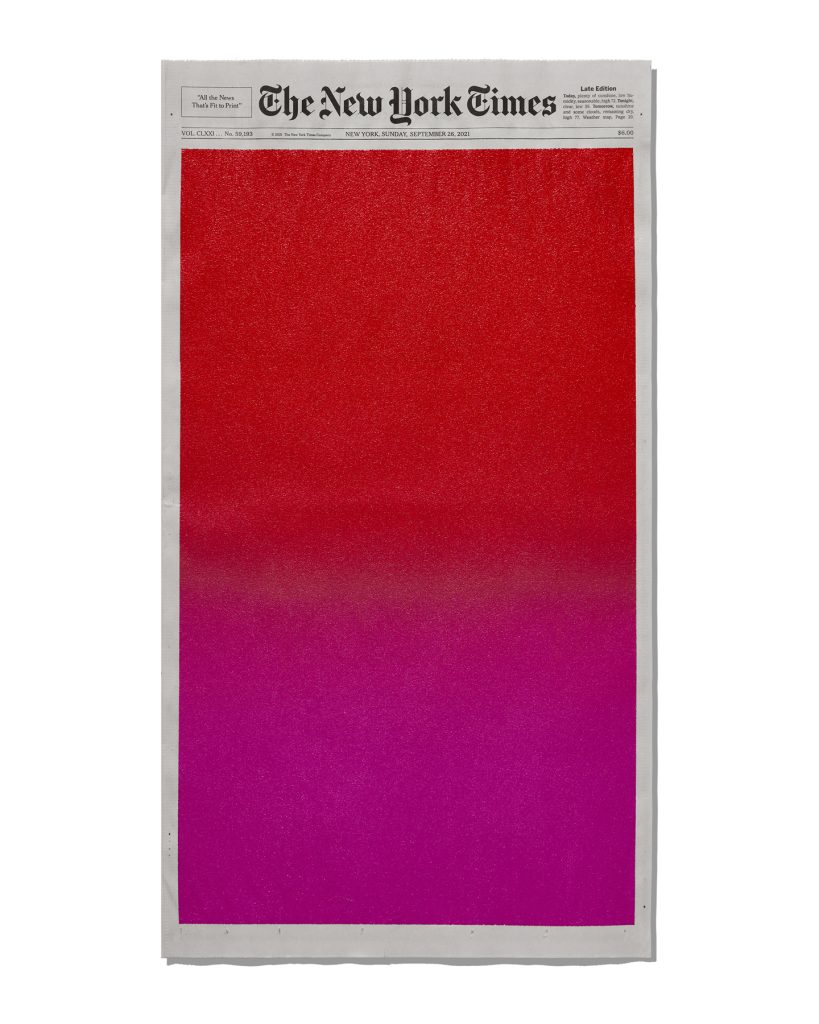

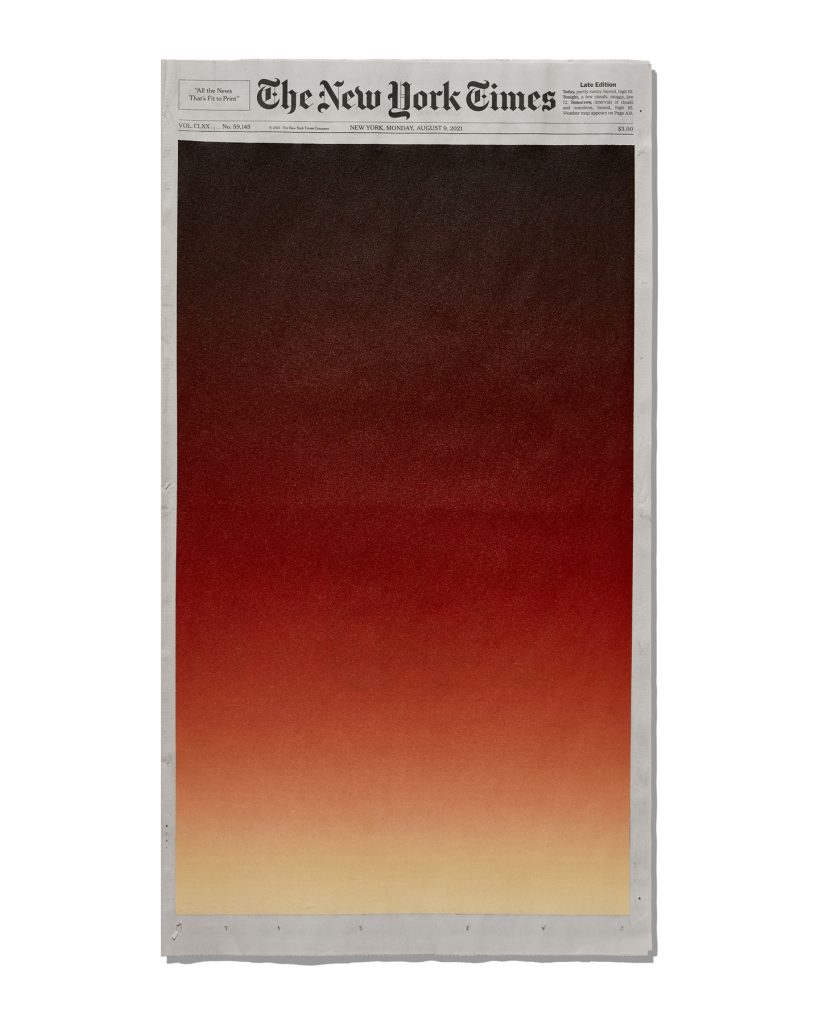

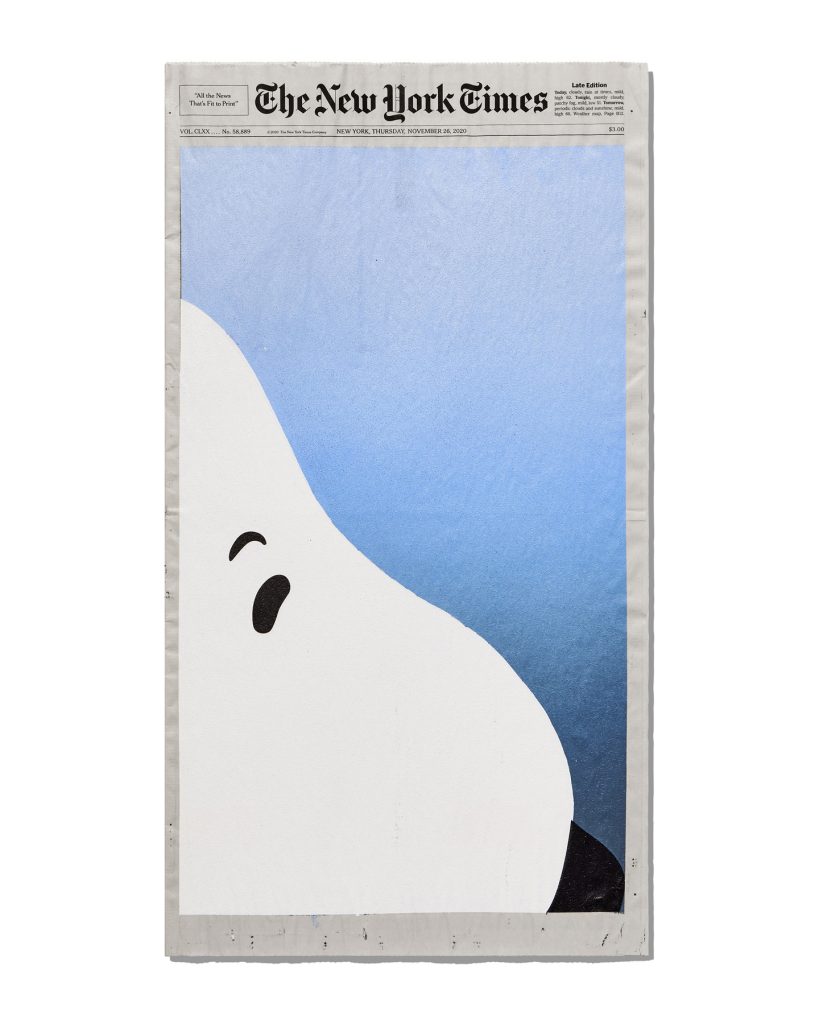

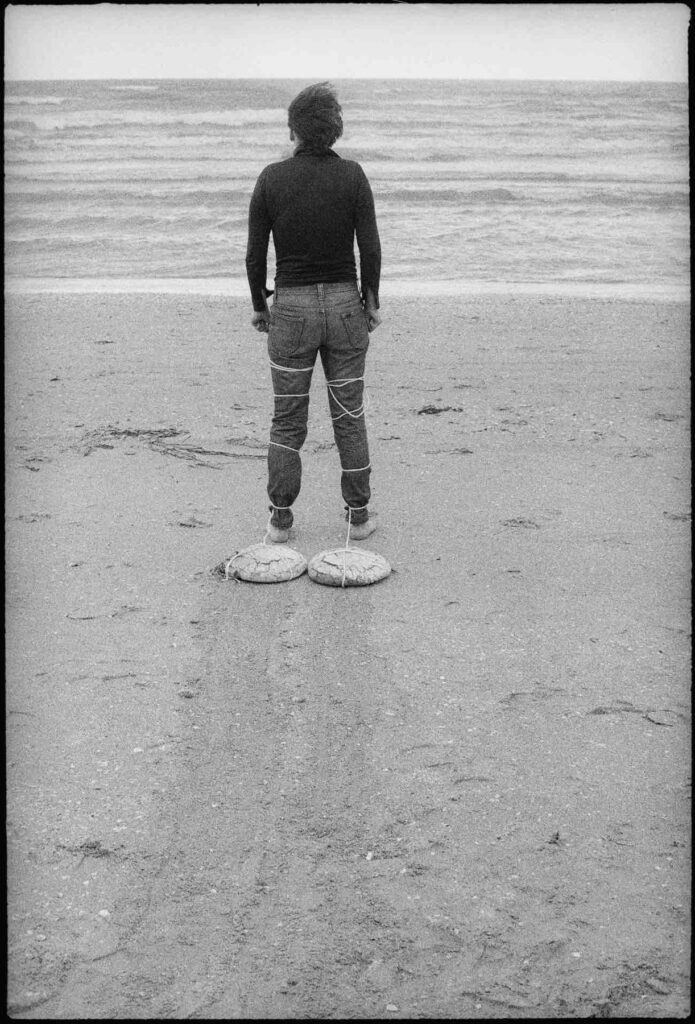

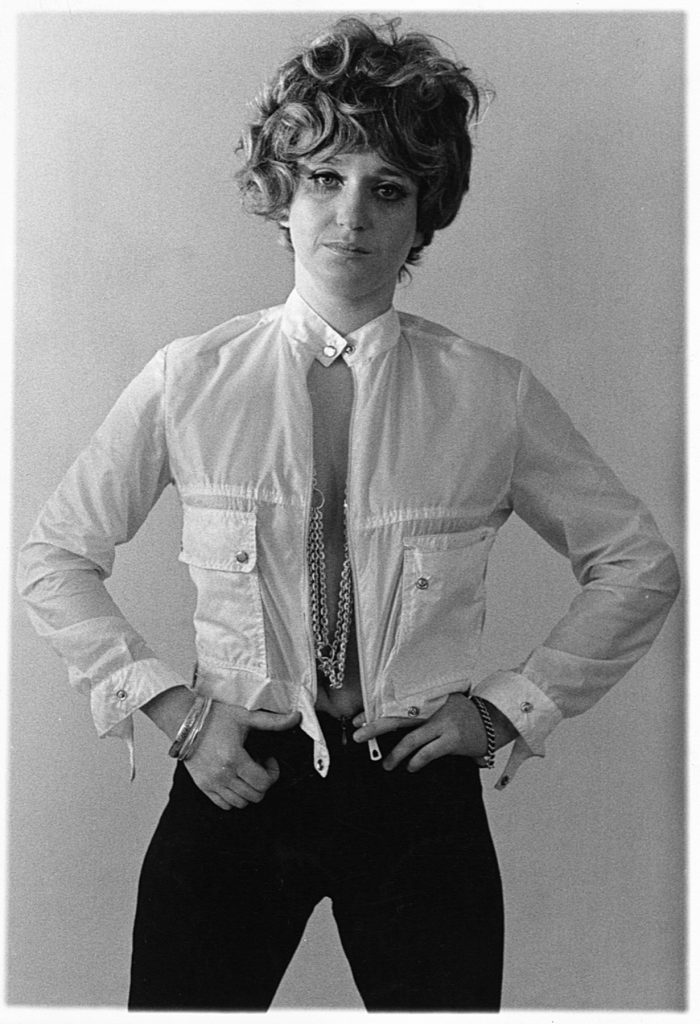

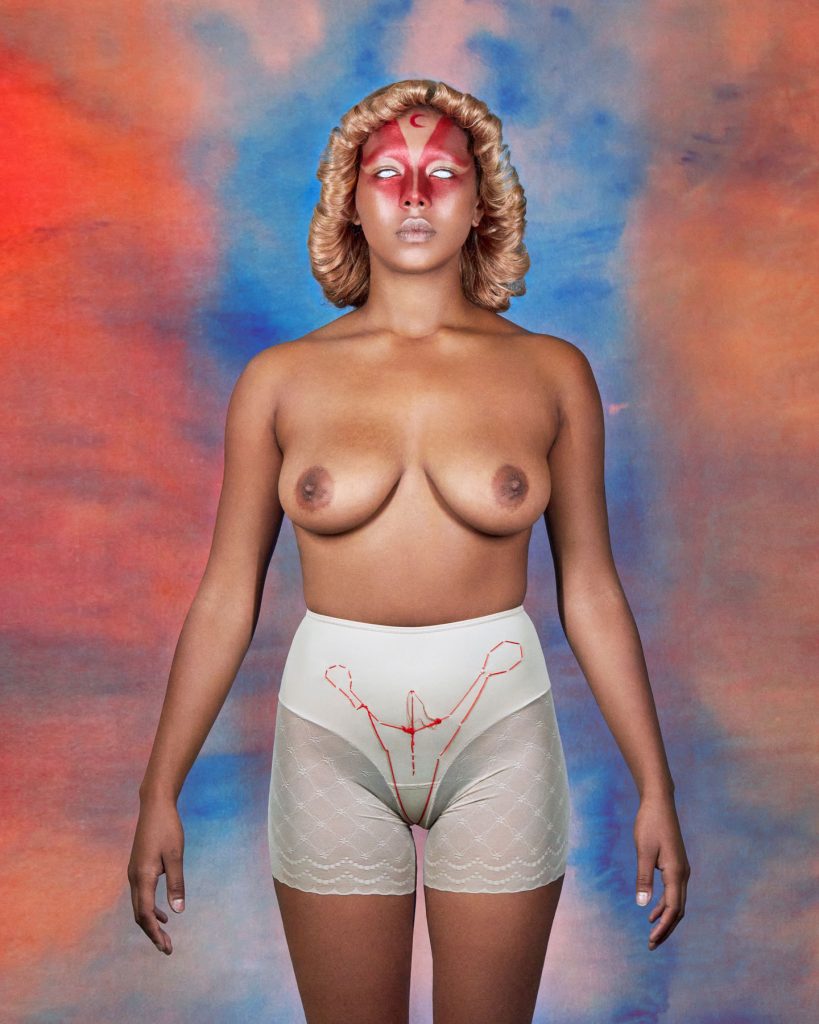

For Alexandra Von Fuerst, photography is a way to explore the relationships between the human body and nature, and how the two are more inextricably bound than we may think. As she explains to NR, her work celebrates the ways in which nature communicates with us. And as the title of her series, Dialogue with Nature (2021) suggests, Von Fuerst uses her practice to share these conversations with her audience. But how does she define this voice that the natural world uses? It is fundamentally feminine, in the sense that it simultaneously conveys empathy and strength. The idea of femininity is another recurring theme in Von Fuerst’s work, but the ‘feminine’, it should be stated, does not necessarily imply gender. In Godification of Intimacy (2021) – Von Fuerst’s first foray into shooting male nudity – the photographer investigates how the body can be elevated beyond what we see anatomically. Von Fuerst explores this idea through the form of a triptych, where the same image is reproduced in different colours – the ‘real’ image positioned alongside two inverted interpretations. In this way, Von Fuerst shows the viewer the ethereal, otherworldly side of her subjects – literally, the ‘Godification’ of the body.

In her work, the photographer’s vivid use of colour is not just an artistic device; it is a crucial element in her investigation into the human form and nature. Explaining below how she came to develop her practice, Von Fuerst speaks of the emotional qualities that colour can have. The photographer is interested in how colours can make her feel, and how the colours themselves feel; and this is a question that she extends to the viewer. Just as Von Fuerst’s work is a conversation with nature, colour, and form, it’s also about creating a dialogue with her audience.

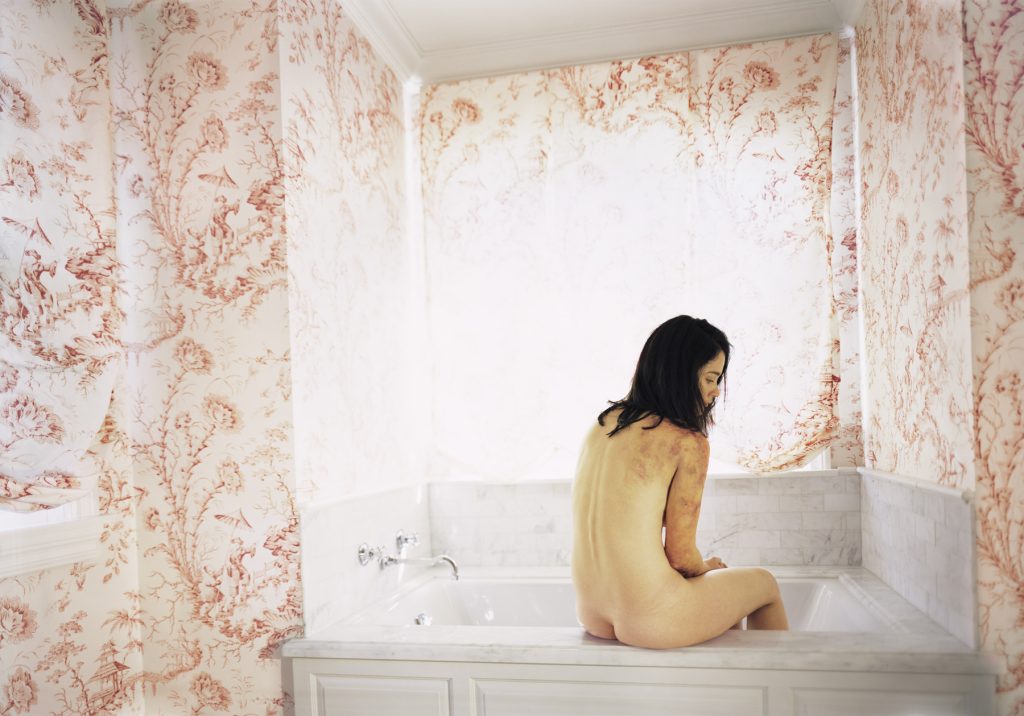

Across her art series, personal and commissioned editorial work, Von Fuerst is not afraid to shy away from subjects and images that some might find difficult. The ‘taboo’, as she calls it, is another of Von Fuerst’s interests; crucially, how can we make the taboo beautiful, and will that allow us to confront and overcome unspoken fears? The photographer handles this with extreme delicacy (even if, as she says, she can be full-on), creating work that is gorgeously rich, without exploiting the difficult conversations that she hopes we can have.

NR: First of all, how does the idea of ‘celebration’ tie into your work?

AVF: Honestly, all my work is about celebration because it’s about elevating everything that I shoot, that I see, and that I’m trying to empower. In particular, I want to celebrate the things that we don’t want to look at, like imperfections. Not only skin imperfections, but things that are much more deeply hidden that we don’t really want to look at because it’s a little bit uncomfortable. For example, this could be blood, or waste, or death. And I think, for me, this is very important, because celebrating and elevating something that feels taboo, or that you don’t feel comfortable about, is giving more meaning to live itself. At least, that’s how I see it. I think that, for me, this is my celebration: a celebration of the imperfections, of everything that is a little bit hidden, and it’s also a celebration of life.

“I think that’s what I care about, making the uncomfortable beautiful, so that it really elevates it to the same as everything else.”

NR: What really strikes me about your work is your distinctive use of colour, and the way you compose your work. How did you go about honing that style?

AVF: I think in terms of the visual style, I knew I couldn’t do it any different. It’s funny, because when I started, I felt differently – I was trying to emulate the photographers I really liked. For example, I always had big respect for Mapplethorpe and his study of the body, or Guy Bourdin’s use of colour. And the photographer duo, Hart Lëshkina, were working a lot while I was at university, so I was looking at them too. And I was trying to [recreate that] but it didn’t happen, and I was like, “goddammit, it doesn’t come out that way – it always comes out bright, pop, a lot of shapes.” So, I was like, “why isn’t it working out? Why isn’t it working that way? Why does it come out completely different from what I want?” And so, at that point, I wanted something else, but I decided to go with the things that actually came out which was very colourful and very bright. So, I learned how to convey that and dived more into shape and colour and tried to dig deeper into how to make it more honest to myself. From something that was initially very pop at the beginning, it became more grounded. Instead of being just colours, it became more about what colour could represent. If you use colour in a certain way, you can really feel it. And I like the idea that people can feel the colour and feel the image. Rather than just the form, I was really trying to feel that emotion, you know; colour for me is this emotional response about how I see reality, in a sense. So, it became a very instinctual, finding the emotional side of myself, which I would also say is a more feminine side.

“Instead of trying to give it a shape, I allowed the shape to show itself.”

NR: That’s really fascinating to hear. Actually, one of the series that I wanted to ask you about is Godification of Intimacy and the striking use of colour there. When you talk about how colour can capture emotion, is that what you’re talking about when you look at this series?

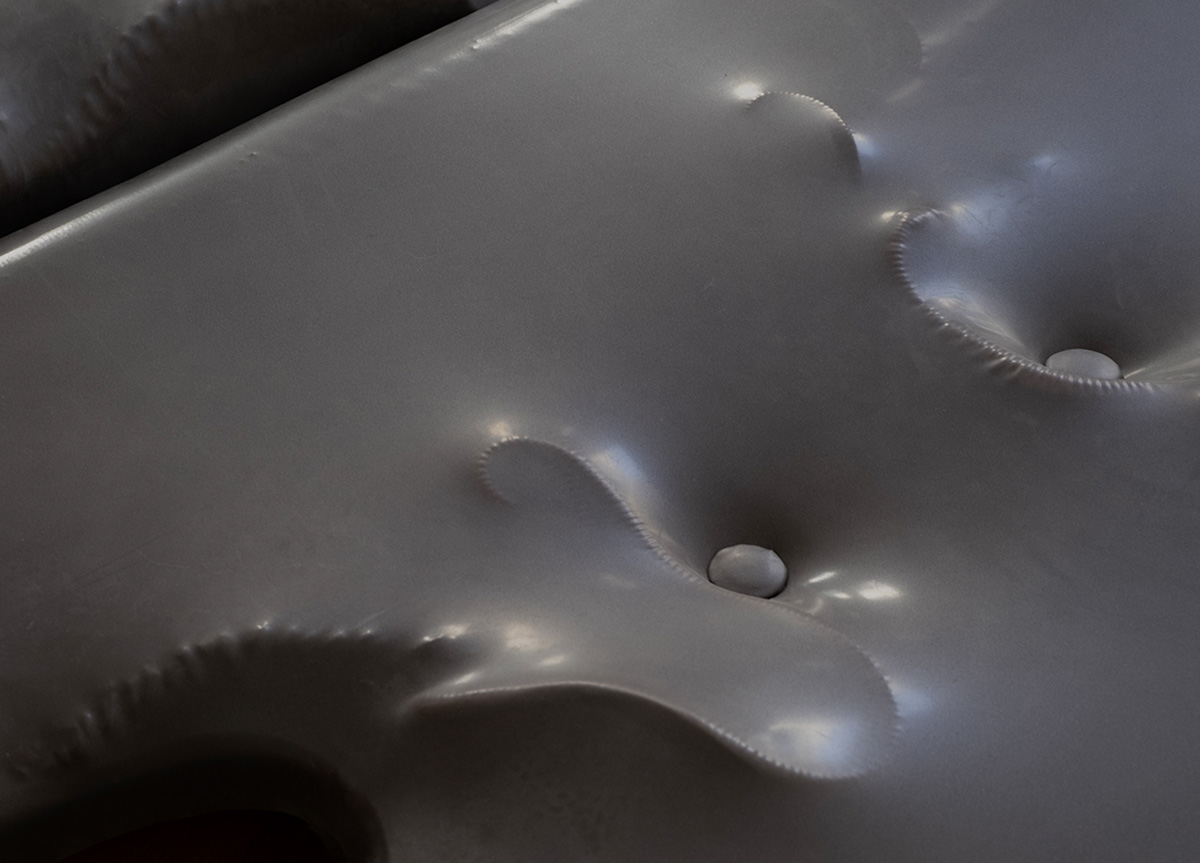

AVF: Yes. I think in general, I don’t say “this is going to be pink.” I really go with if it feels pink, or it feels another way. Godification of Intimacy was my first time shooting male nudity. It was just me and two models in an empty space, and I really wanted them to just interact and to move and to have that sensation of dancing and comfort. And it was something very new for me because it wasn’t how I would usually work, and so it was really about allowing it to grow and to move and it was such a beautiful experience; it was such an intense experience as well. There was a connection between the three of us and there was nothing else – it was just that moment and that sharing. So, I think the colours somehow are very elevated because that moment was also very elevating, which is what I wanted, in the sense that ‘Godification’ is about the higher state of ourselves, rather than just seeing the body. I’m not talking about the body, I’m talking what is behind the body, what is beyond the body. So, the colours are almost as if I’m diving into a spiritual expression of the body, depicting the energy around it, rather than just what I see. And the triptych, for example, is an evolution from how seeing it plainly to an expanded point of view where it’s not about the body anymore. It’s not about the nudity, it’s really about whatever comes beyond that.

NR: That’s really interesting, especially your point about moving beyond the body. Again, something I’d like to ask is that, as well as the body, objects with an anthropomorphic quality often feature in your work. Do you approach the body and objects differently as your subjects?

AVF: Not really. I mean, whenever there is a human, I approach them as if they were a sculpture. And whenever there is an object, I approach it as if it was living. So, for me it’s kind of the same. It’s different in that you enter differently because you’re trying to give more movement to one and less to the other, right? And you want to bring them to being on the same level; I don’t want to give more, or less, life to one of them, I’m just trying to make them equal.

NR: Your work explores the notion of femininity in different ways. How does your use of the natural world allow you to convey a sense of femininity?

AVF: I’ve always felt that there was such a feminine voice within every aspect of reality; it’s the organic, nature, and the body. Even shooting male nudity, for more it’s about this female voice, or softer side. It’s not necessarily soft because being a woman can mean very strong and empowering. But it’s much more fluid, more empathic and understanding – but it’s also direct, too. A big part of what I’m trying to get into is really giving a voice to the organic because I feel like there is so much depth there. It’s just a different sort of communication in a way – that’s why A Dialogue with Nature (2021) was born. Because for me, it’s the natural, organic aspects of the everyday. Nature talks to us – it is trying to communicate something to us. It’s just that the way they do it is very different – but I find it very feminine. You can stand in front of a tree, a plant, a rock or a mineral and see how complex it is. When you look at how many shapes it has – you could stay there for a day just looking at it. And I think all of these aspects of this organic material, they are actually talking even though they’re not speaking; they don’t have a voice as we would perceive it.

NR: In our correspondence, you mentioned that you prefer doing interviews over Zoom rather than email because it feels more personal. I read that during the [2020] lockdown you made yourself available for people, strangers, to call you. Why was that important for you?

AVF: When lockdown came – I’m a person who is happy being alone, but I realised how even for me at that point, it was stressful. All of a sudden, nobody wanted to communicate with anybody else because there was so much fear. I think it became so important to just try to go the other way like, let’s keep it open, let’s keep a dialogue. I thought to do the best with what we have and stay in a more positive space. I said to myself, I have time I don’t have like any rush, and I can consecrate some time to someone who was having a bad day or is having a good day.

“I think communication enables you to let go of fear because all of a sudden, [you realise that] I’m not alone or, it wasn’t that hard to talk or, it wasn’t that scary. And it also brings a human perspective.”

NR: You mention there about how communication can allow you to let go of fear, and I wanted to tie that back in with what you said earlier about celebrating the taboo. Do you see your work as shining a light on things that people might fear in a beautiful way, so that we can breakdown the fear of the taboo?

AVF: I really hope so – that’s the sense of it, which is that I’d like people to try to look at fear and not reject it. To actually look at it with more love and more joy. I know that, sometimes, it’s very direct; as my mother would say, you need to be a little bit more delicate in the way you’re dealing with things. Sometimes, I’m being direct, but my intentions are to make [the taboo] more accessible and more discussed. I mean, my work is not just about the picture; it’s about being able to start a discussion or create dialogue, to create accessibility. I think, for now, I’m really just at the beginning of this process, but I’d really like it to become a window for people to really have a discussion to start seeing things with more acceptance. And I think the moment that discussions are open, the moment communication is open, ignorance [towards the taboo and fear] disappear because all of a sudden, you’re facing it. You’re talking about it, you’re solving it. So, I think communication is very, very important.

Credits

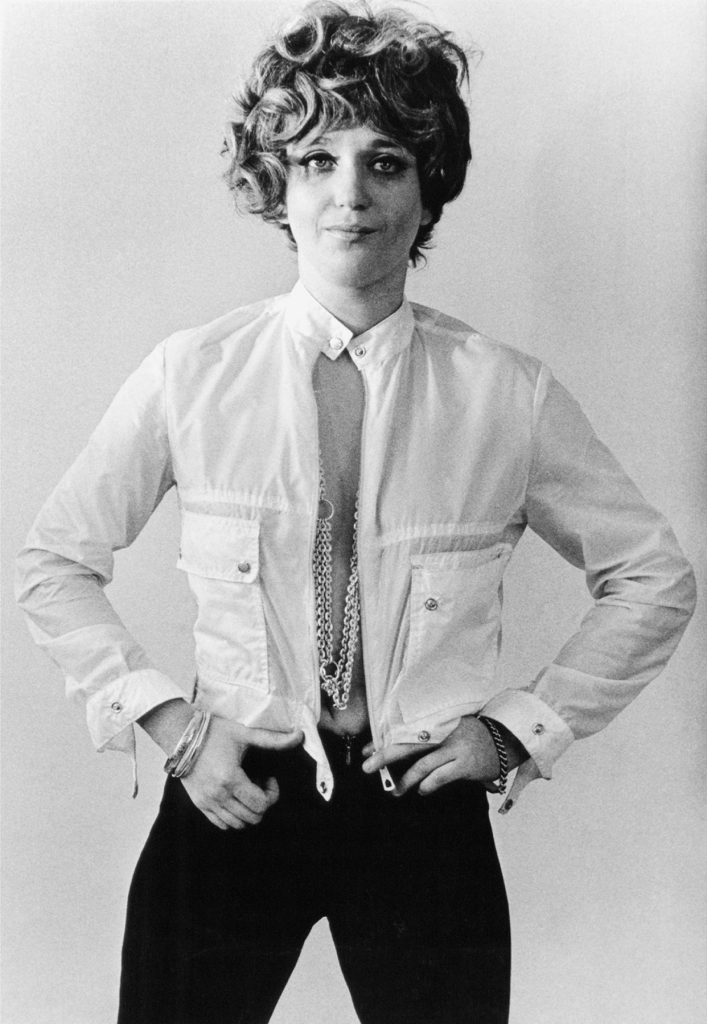

Images · Alexandra Von Fuerst

https://www.alexandravonfuerst.com/