“do as little as possible”

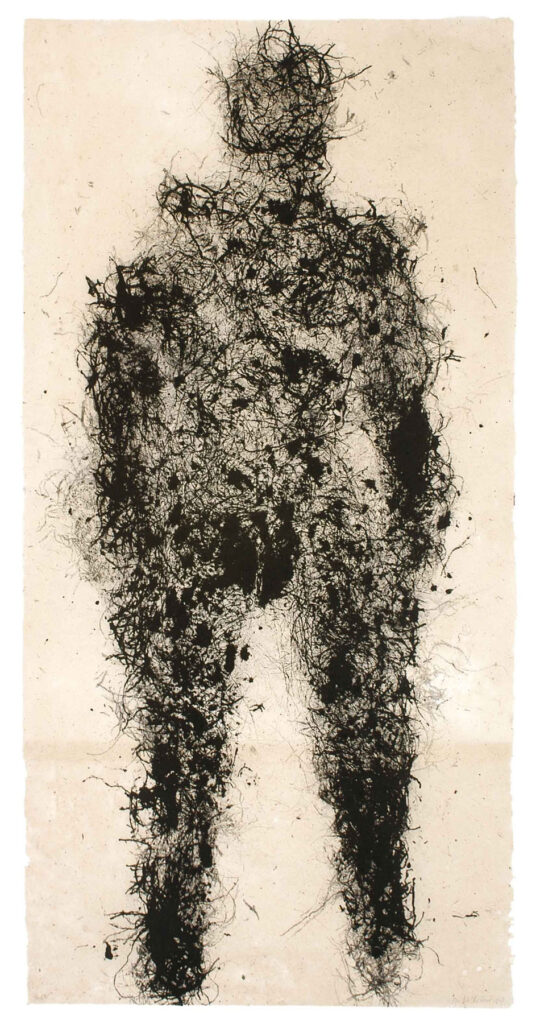

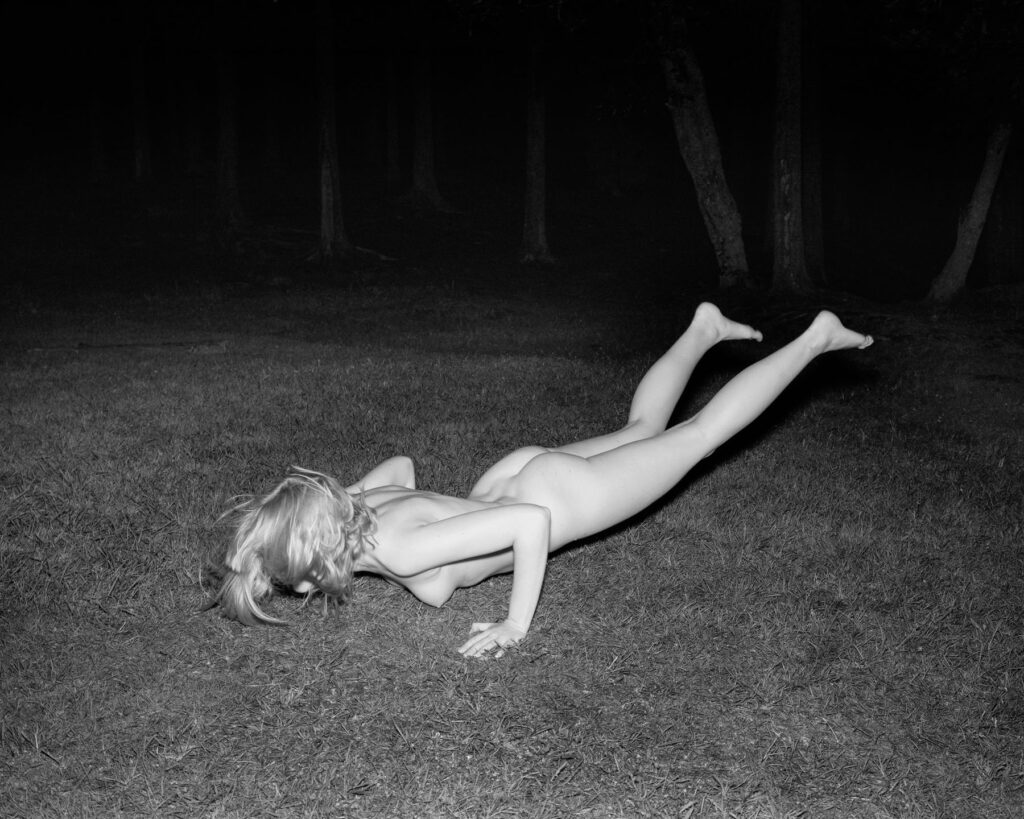

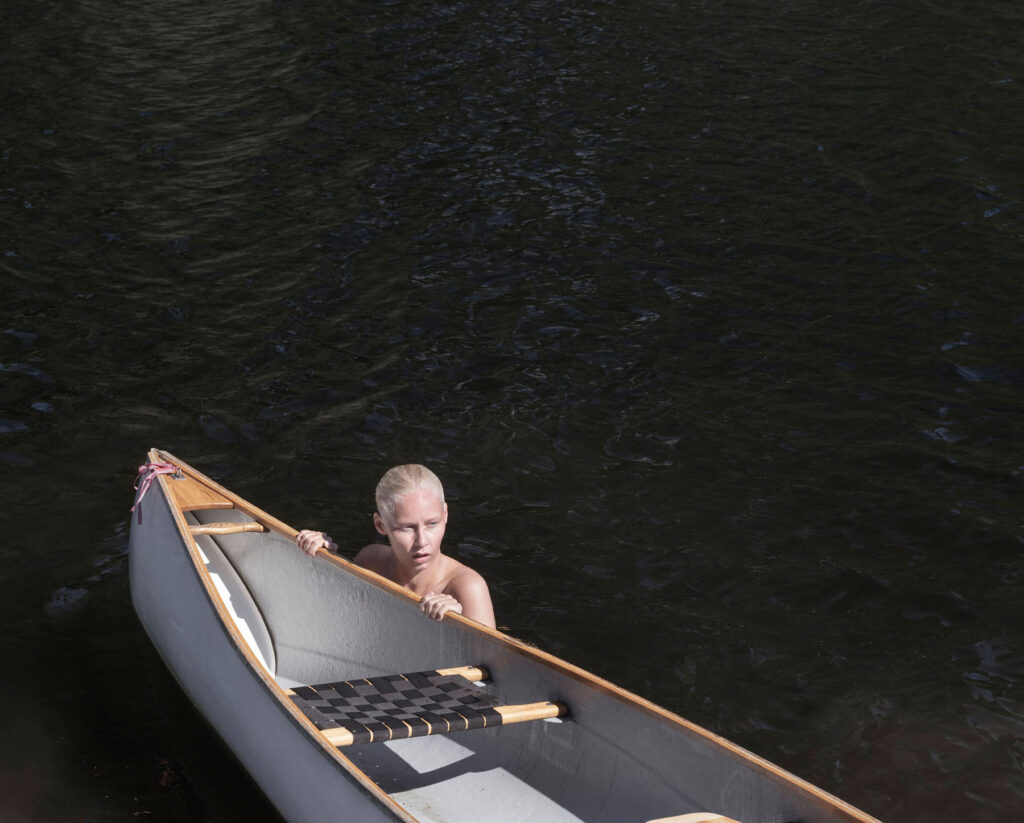

In GT Nergaard’s photographic practice, the intersection between fiction and reality offers the grand gesture of self-portraiture. Every photograph reflects his journey towards discovering personal narratives that have shaped his background, artistry, and thoughts. As he builds his themes around these philosophies, he creates photographs based on his imagination and observes a situation through his lens, all while forming a bond of who he is and how he wants himself to be.

Through a monochromatic palette, the Norwegian photographer includes his viewers as he fuses self with nature. A Vitalist at heart, he employs the life force in living things to calculate his shots and summon delicacy, grace, and rawness in his photographs. With the sun as his source of light in the day and the flash of his camera at night, GT captures the interaction between man and nature, eliciting poetry in visuals and autobiography in practice.

Let us begin with the two sections that divide your online portfolio: North and South. Do these pertain to certain locations? What was your idea behind these projects? What did you aim to capture?

The inspiration for my work comes from the locations I photograph in, using the sun as my main light source. Based on climate, I work simultaneously between these two projects in different locations: one in the summer where I shoot in Norway, and the other in the winter where I travel to southern regions, North and South.

For the last ten summers, I have been working on the Storvatn project, recently published as a book. Storvatn is the name of the lake where my family had a cabin thirty years ago and my childhood paradise. In this project, I travel back to the lake in search of my own identity and to reconcile with my past, the time being just as long I have been working on a project in Essaouira, Morocco. Then, when the winter in Norway is at its darkest, I travel to a warmer climate. The project is a very personal and poetic interpretation of Morocco with the working title birds of passage and will be published as a book in the Autumn of 2022.

We are excited about this new project you have! This ties up to how you identify your work as at the crossroads between fiction and reality. Why did you settle on these themes and not other elements? How do you define fiction and reality? In your daily life, do you dwell in fiction, reality, or both?

For me, photography is a medium where I first and foremost convey a personal story and a reflection of myself. The work is like a parallel world, where reality and fiction intersect and create a new narrative. I define fiction as creating photographs based on my own imagination. Reality is when I am an observer in a real situation I have not constructed, and where I take photographs without manipulating them.

It is difficult for me to relate to just one of the methods since they are interdependent, just as I relate to a dream world when I sleep and reality when I am awake.

“The dream may appear surreal, abstract, and difficult to interpret, but intends to create a balance in my life to make it easier to deal with reality.”

It is wonderful to know how reality and fiction balance the dynamics of your life. I wonder if this thought is a root of your work, which is strongly influenced by vitalism. Could you elaborate more on this? How did this occur? Was it an intentional choice to pursue it?

Years ago, I saw an exhibition at the Munch Museum in Oslo with the theme Life force – Vitalism as an artistic impulse 1900 – 1930. The term Vitalism comes from the Latin word Vital and is based on the assumption that there is a life force in all living things. The artists in the exhibition represented a distinctive period where body, nature, and health are at the center and the cleansing power of the sun as one of the central themes. Among the Norwegian artists from this period are the painter Edward Munch and the sculptor Gustav Vigeland. Their works show nude people engaged in play, swimming, and sports, with nature as a backdrop.

From the Vitalists, I affirmed my photographic style and a philosophical understanding of my own concepts. I do not draw direct inspiration from their work, but from a common motivation in the theme.

You interpret the interaction between man and nature in your photography. What discoveries about this interaction did you find out that fascinate you and influence your art practice?

My attraction to nature as a theme comes from a personal need and a simplification of the photographic process. Ten years ago, I worked as a commercial photographer in fashion and advertising. The working day consisted of large productions in the studio, a lot of technical equipment, and a large crew. At one point in my career, I came at a crossroads, where the result was to find my way back to the freedom I felt when I started as a photographer and a simpler working method.

Today, there are no clothes, hair styling, or makeup on my models. Everything is done in an outdoor location, and the sun is the only light source with the exception of an on-camera flash at night.

“None of the images are manipulated or retouched in photoshop. With this simplification, the inspiration to create gradually came back, along with my photographic identity.”

Continuing the previous question, there is a sense of freedom in the way your subjects embrace confidence in their bodies. As a photographer, how do you interact with your subjects? How do you know when to capture the scene? Have there been any challenging times during your shoot?

I depend on finding people I work well with, who are free by nature and have an understanding of the concept. Many of the models are artists themselves and have a clear awareness of their own bodies and identity. They are equal partners who I have worked with for many years and consider my friends.

I prefer to create a natural situation where I can photograph without taking too much direction. The ideal situation is to travel to a location for several days where the narrative and images occur more naturally. In such a setting I can work both day and night, which gives the story a sense of time and space.

I have two ways of directing. In the first, I take a clear direction and do a controlled study, shaping my subject with light and shadow. In the second, I work in a snapshot mode where the subjects are in action and I direct more intuitively.

“I think the alternation between the stylized and the random makes the project more dynamic and playful.”

I have never experienced situations during a shoot that I would describe as challenging, with the exception of the Norwegian climate. In my region, we can experience four seasons in one day, which can make it challenging to work outdoors with nudity.

Your photographs evoke a sense of timelessness through their monochromatic colors. Is there a reason for this choice of style? How do you work with light in this case?

Today, I think it is because I am a monochromatic person. Everything I own is black, white, or natural wood, with only a few touches of color, a natural choice and typically for a Nordic minimalist design.

In the beginning, it was more of a practical choice since all work was processed in the analog darkroom. I have always been attracted to a classic and timeless expression. Not only in photographic references, but in film, music, literature, and design. I draw a lot of inspiration from contemporary references as well, but the classic is always my starting point.

I am often asked how I work and manage to create the specific quality of my photos. The honest answer is: to do as little as possible. I work based on a ‘Pure Photography’ style where the photographs are created through the control of composition, tone, light, and texture. There is no use of manipulation and effects.

To wrap it up, how do you perceive the body, nature, and health? Are they distinctive or combined entities of life?

Today more than ever, I feel it is important to reflect on the role of humans as part of nature and how dependent we have always been and still are on each other. By taking better care of myself and living sustainably, not only will my health and body improve, but I will also take better care of nature. Everything is interconnected.

Credits

Images · GT Nergaard

https://www.gtnergaard.com/