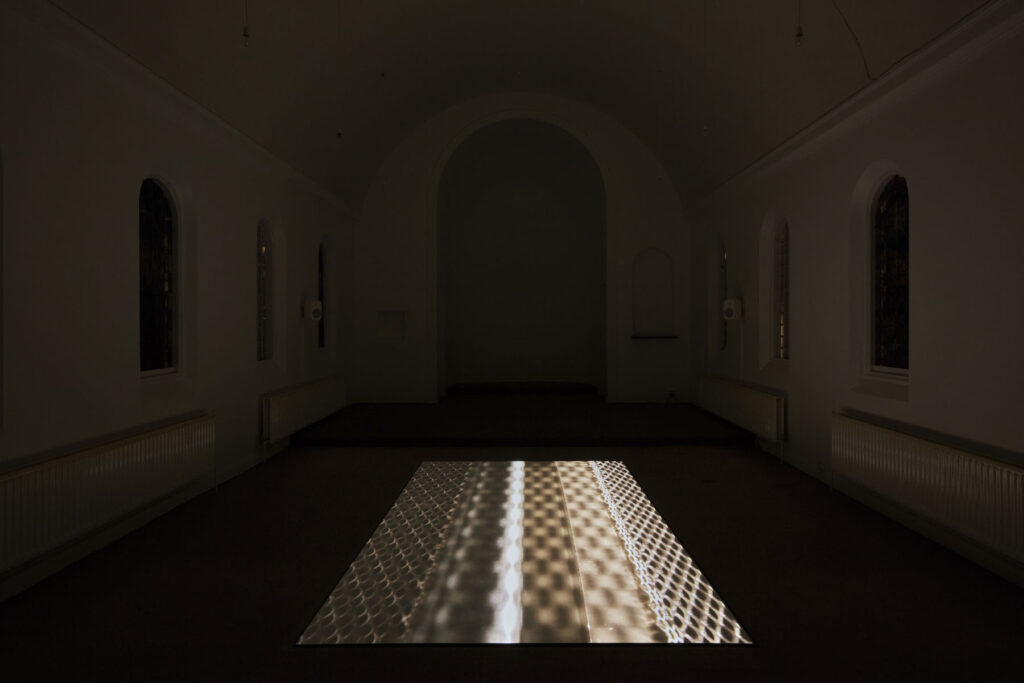

‘Silt’ a 35 minute documentary film produced by Iida Jonsson, Ssi Saarinen and Ona Julija Lukas Steponaityte, is an exploration into the post-soviet landscape following the formation of rapidly occurring lakes in Lithuania, one of which, rests on Lukas’ family land in Likanciai. The newfound body of water is a by-product of a failed multi-decade soviet drainage project, aimed at making wetlands more suitable for agriculture. Following the collapse of the regime, the Lithuanian municipality gained responsibility of such drainage systems, but high maintenance costs resulted in the prioritisation of farmland and infrastructure. As time passed, the drainage systems started to clog and what was once a drainage pipe, became a vessel for a lake to emerge on the family’s backyard.

The documentary demonstrates the group’s interests in the rendering of landscapes and is a response to the embedded narratives within it that influence our understanding of ecological emergencies, and the relationship between the landscape and systems of maintenance. The visuals are accompanied by a sculptural sonic landscape produced by composer Alexander Iezzi, referencing the historical interrelationship between landscape and sound. The dissonant harmonies, polyrhythms and metallic growls, coupled with foley and field recordings are almost reminiscent of musique concrete styles of music, providing the perfect soundtrack to the unnamed, unmapped lake.

Following their most recent exhibition ‘November’ at Inter Public and the screening of ‘Silt’ at the Danish Film Institute in Copenhagen, I had the pleasure to talk to them about how their collaborations and inspirations inform their approach to the creative process and their relationship to the entangled landscape.

I noticed you all completed your MFA degrees at the Sandberg Instituut in Amsterdam, is this where you first met as collaborators? How did this shared experience help you grow in your individual creative practice’s and come together with a shared artistic vision?

SSI: Iida and I were already collaborating, so we are used to sharing a project and practice. But yes, all three of us were studying the Master of Fine Art programmes at the Sandberg Instituut and this was the starting point for our collaborations. We had shared interests, and we just admired each other’s work. We were all interested in this idea of an accumulation of knowledges and bringing in our own experiences to our collaborative practice and approach. We were already working with similar topics, so for us, working together, was a way of making the work more rich, opening up shared discussions and accumulating these pools of knowledges.

LUKAS: We know each other’s aesthetics well and we know what we are interested in. There is definitely a process of building a shared library of references and a vocabulary of shared aesthetics that has a big impact on the work. We also have similar tastes and sensibilities, so we have a lot in common which creates a good basis to develop a shared language together.

S: We are also coming from similar professional backgrounds, but we still have different perspectives and skills we can bring into the work. For example, Lukas was working as a professional colourist, and Iida and I used to run a production studio, and I have also worked as an editor and cinematographer before. So when we talk about collaboration, we are bringing in our different skills and knowledges to our practice.

I’ve noticed that you don’t work under a collective name, but instead, you use your own individual names to credit the work. Why do you feel this is important to you and how does this impact your collaborative processes?

I: I think there is a certain openness and honesty to it which is interesting. Maybe there is a fourth or fifth name added to the collaboration in the future? So I think it allows us to expand and change shape to become different things.

S: I think to a certain degree, there is still a sense of separation within the work as I can recognise myself in the work and see the parts that have been touched by Lukas or Iida. Additionally, there is an entanglement in this; where our individual expressions are also informing each other, and we are benefiting from one another. So, there’s this intersection of aesthetics and ideas which becomes how the group work is ultimately presented.

I: We are also not crediting our individual roles within the work. It is still a shared process where we are all involved in the conversations and the various tasks that need to be executed. As Ssi mentioned before, it is really useful to bring together our individual, extensive research and knowledge that has been accumulated over several years.

You have worked together before to create the works ‘Terranium / Greywater’ and ‘June’. What do you enjoy about working together and what is important to you when collaborating? How has this facilitated the creative process for your recent exhibition ‘November’ and the production of ‘Silt’?

I: Being a fan of the people you work with is really important. You can really encourage and support people to invest in their work and their ideas by being a true fan of your collaborators.

L: A big part of our work as a collective, naturally comes down to talking. We need to find common ground on an idea or a vision which happens through communication. We spend a lot of time talking, understanding and approaching the shared vision in various ways. This also always comes with challenges, because communication is often one of the most challenging things when it comes to people.

It is also interesting, when working in a collective to see how your own individual expectations towards your production, expands. For me, collaboration allows me to do things that I would not necessarily be able to do alone. So maybe it is also about feeling more brave when you are working with people.

I: Yes I agree, because ‘Terrarium’ was a film using found footage and ‘Greywater’ was an installation, so ‘Silt’ finally gave us the opportunity to create something from start to finish, using all of our interests and skills in a complete way, giving us the opportunity to do everything we had talked about.

I’ve noticed your works are often inspired by the environment, exploring sites of environmental or urban decay. What is it about ‘landscapes in depression’ that inspires you artistically and what draws you to these kinds of landscapes?

S: I think this idea of the landscape and landscape depiction is very essential to our collective practice. Our research expands way back into landscape depiction in the 16th century, looking at the political intentions in mappings and topographies. We are especially interested in the use of landscape depiction to exercise power, focusing on how embedded ideas of nature dictates the way we should experience and interact with the landscape, creating this very essentialist view of an unchanged or static image of the environment. So I think we are working with complexifying this image and contributing to the discourse around it.

L: We aren’t looking for places where urban meets nature. For us the relationship is so entangled, there is no point in finding where one starts and the other ends. We want to talk about this crazy entanglement between the two, and the messy consequences of it.

I: What is also interesting, is, when you constitute the landscape, you also sign up to a variety of infrastructural injections such as, building bridges, maintaining trenches and constructing hiking trails. So there is an enormous number of resources and effort going into maintaining the static image of the landscape. This is specifically interesting for us, the landscape always comes with intention.

Often times, the landscape is undergoing constant change; people throw trash in the street, they create new footpaths in a field, but the government often intervenes to counteract these events, creating an interesting dynamic and tension between the ever-changing landscape and systems of maintenance.

How have your experiences, growing up, studying and living in different cities, shaped your relationship and understanding of the entangled landscape and how has this influenced your artistic process as a result?

L: We tend to work with stories and images that are accessible to us, so naturally this leads to working with images and ideas that we are surrounded by. ‘Silt’ is the most literal example of that, the film is about the sudden formation of a body of water in my family land, where I grew up. The land has been with my family for generations and naturally because of that, there is a story to tell about the soviet occupation in Lithuania and its impact on the nation and the landscape.

I: It wouldn’t have been possible to make ‘Silt’ without Lukas having this really personal relationship to the land. It is important to have a person in the process that has a strong cultural relationship to the site at hand because only they can see the various nuances that you can only understand through spending a lot of time with this culture and space.

S: Iida and I come from rural Finland, so we have a tendency to relate to those types of spaces and images. I think aesthetically this is the language that feels relatable to us because we understand it. The subjects of our films are about the entanglement of environments, and I think we are more asking the questions; what is shaping our experience and what are the signs that are given to us to navigate? We are interested in understanding and complexifying these signs.

In ‘Silt’ we were influenced by a landscape painter called Petras Kalpokas, who made a series of paintings depicting Lithuanian rivers defrosting after winter as a symbol of resistance against the soviet occupation. We were also looking at painters from the Finnish Golden Age spanning from the late 19th Century to the early 20th Century.

I: What is interesting about these artists, is that they both existed in a time of resistance, through the independence movements of Finland and Lithuania. So there is a clear inspiration for us in these two examples of how you can use art as a political mediator.

For your most recent exhibition titled, ‘November’ and the production of ‘Silt’, I have noticed that you have worked with the found materials within the landscape and incorporated these into your pieces. There’s a certain level of transparency and honesty between the subject and its representation within the art. What role do these materials play in the meanings of the pieces?

L: In ‘November’, we used disused solar panels and silt from the water, a found material that is like dust of the water. We were interested in thinking about the landscape as an event and the solar panels as ambassadors of such event, almost like how photography film is the ambassador of its subject when it is exposed to light. So, the found objects are almost like canvases, we develop them into something new as we respond to the found materials.

I: There is a honesty to it but there is also a dishonesty to it. The ways the objects are re- arranged and dealt with always becomes an interpretation of the space and the material itself. Any kind of documentary, painting or photograph is always altered and dramatised by the author. For us, there is sense of liberty in this; When we start to acknowledge the individual’s interpretation of a subject, we can start to critically analyse the tools used, start to construct narratives and create art that might have seemed untouchable before.

You often use film within your works. Why did you feel film was the most appropriate artistic medium for ‘Silt’, do you feel that film can portray something else that other mediums cannot? What is it about film you enjoy working with?

L: There is something beautiful about film being a container of many different skills and tools that can be used to tell a story. It has a duration and demands time of attention, more time than a still expression and it is important to sometimes ask for time from the viewer.

I: There is also a sense of accountability in this because you are taking someone’s time. I like the duality in this, you demand time from your own practice as well as the viewer’s.

S: We also all have previous experience making films. So it is a medium we all feel we can be very precise with and it is a medium we know how to use to our advantage. It is a craft we have invested a lot of time into learning, and we enjoy it because it creates an experience for the viewer.

I: I think it is important to embrace the crafts and the skills that you have. I don’t want to be an interdisciplinary artist, I want to be a disciplinary artist. It’s like when playing an instrument, you play the instruments that you can play. I think this is when you have the potential to say something really sharp, in a precise way that resonates with people. With film, we all have that close at hand.

Do you feel film, offers you a sense of freedom through creating limitations as it provides you with a framework to work within?

I: I think working together is a lot about this, establishing various frameworks that you can collaborate within and film has been one of those frameworks for us, like a playground.

L: There is also something very nice in letting the tools and materials you have dictate the content of the work. It creates a sense of openness which is developed through practicing the skill.

S: There is a text that compares the control over an artistic medium to weaving a basket. The shape and form of the practice is coming from the precise application and strength that you put behind each knot being weaved. It takes multiple attempts to know how much pressure to apply to a certain part and where you should be more careful. It takes time to be able to understand how to emphasise parts and how to portray a narrative through the work. When making a film, I enjoy how you can direct the way you narrate the story and you know how to guide the viewer through the narrative, when you want to do that.

What was your thought process behind the composition, script writing and assembly of the scenes within ‘Silt’ and how did this serve the narrative you were wanting to tell?

S: The film is basically divided into three different parts, and they all come from the videography styles of television broadcasting and documentation of sudden events. The first part of the film is filmed from the point of view of the cameraman. When we were devising those scenes, we were looking a lot at how sudden events are filmed by the by-standers, we were inspired by the sense of intimacy and immediacy portrayed in handy-cam footage of real-time events.

I: There is something beautiful about the ‘vlog’ video format because often, the cameraman and the cinematographer have discovered something simultaneously, so the encounter captured is very immediate.

L: In ‘Silt’ we are portraying this new body of water that has suddenly appeared as a result of a failed drainage system. Through borrowing languages from broadcasting videography, we are able to visually translate the speed at which this new lake has emerged. As a child I could run on this land, but now I can only swim there. So there is something also quite sci-fi-esque about the speed of this event occurring.

S: For the second part of the film, we approached the lake with more of a forensic lens. Focusing on what is happening under the water through the leeches and floating algae. During this part, we wanted to draw attention to the bottom of the lake, which was once part of the land. You can see the trees that were once emerging from the ground and growing on the field as if it were only yesterday. We are creating these clear images of a field that has been flooded and showing the new life that has started to emerge in this new lake. When we were writing these scenes, we were drawing inspiration from forensic discoveries of shipwrecks.

The last part of the film uses visual languages displayed in television broadcasting footage, taken from a helicopter view. We imitated a lot of camera movements from footages of volcanic eruptions, and we used these tools to portray the vastness and the scale of the lake, giving the viewer another perspective of the event.

I: A question we were exploring in our process and method was, ‘how can we capture something so serene and still while also showing the violence and rapidness of the emerging lake?’

The aesthetics of the film are cold and dark referencing the decay of the soviet infrastructure in the ‘depressed landscape’. What were you aesthetically inspired by and how did this influence the production process in ‘Silt’ and help you communicate the narrative you wanted to tell?

L: Digital colour grading possibilities are endless but at the same time the image is often dictating its own rules, so you are always adapting to the rules of the existing image. Sometimes it offers its own solutions and so, it is about attuning your eye to what the shot already has and then interpreting it further.

I: We have also talked about the false pretence of the documentary as a style, discussing this false idea of the neutral documentation of an event. Many people ask for neutral colour grading for a film, but there is no such thing, the footage and the image is always reinterpreted.

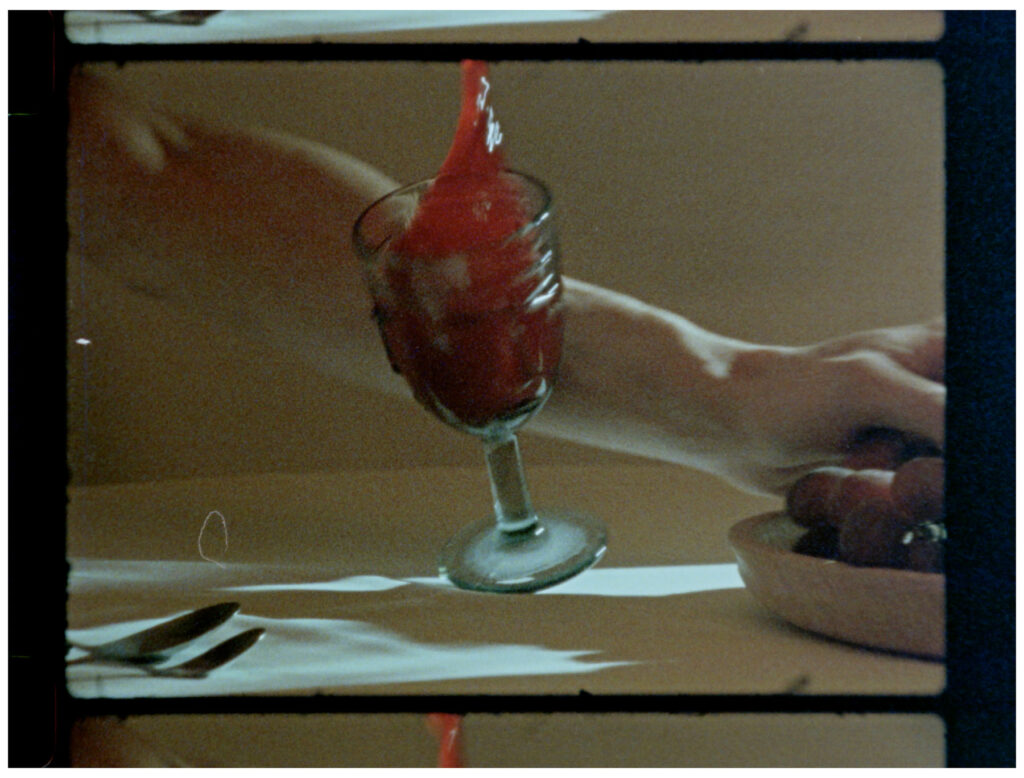

There’s also this element of horror in the film, I was reading about gothic literature at the time and I was inspired by the separation of terror and horror. Terror being something you anticipate and horror being something that’s already happened. I think the film holds a little bit of both; with horror being in the emergence of the lake and terror in the potential scale of this lake. I think the colours also help reflect this tension and emphasise the depressive state of the land.

The film music is composed by artist, Alexander Iezzi who releases music under the alias ‘33’. What was it about their work that inspired the collaboration? How did you feel their work and sound design complimented the aesthetics in ‘Silt’?

S: We work very sculpturally when we make film, drawing inspiration from a variety of sources such as 16th century cartographies, romanticist and modernist landscape paintings referencing different parts of art history and political ideologies that have dictated how spaces have been perceived. In a similar way, Alex’s work draws inspiration from a variety of genres, from metal punk to baroque music and is also assembled in a very sculptural way as these inspirations are collaged together creating both abstractions and figurations of the music. So, we could definitely see ourselves in their way of working, we could resonate and relate to their musical productions.

The textures and sounds used in the soundtrack of ‘Silt’ are also very sculptural. Do you think this style of sound design lends itself to the themes of horror and terror Ida described? How does the sound design help deliver the narrative you wanted to tell in ‘Silt’?

I: Creating a composition that embodied the history of the lake was important to us. This is a new lake, very few people know about its existence, and it is also a tragedy for the people that live with it. We worked with alarm sounds and bended them into violins and used the helicopter sound from the television broadcast footages we had used for visual inspiration for the film. So I think the textural layering of these different sounds and the sculpturing process behind the composition helped us narrate the story of the lake.

S: As with landscape depiction in painting, there is also a long history of landscape depiction in music. In Finland one of our most famous composers, Jean Sibelius, is known for having created this piece called ‘The Spruce’ about the Finnish forest. So it is interesting to relate the making of music to the portrayal of the landscape and understand how music can also feel like a painting or a portrait.

Do you think the piece almost challenges the traditional way music has interpreted the landscape in the past?

S: I think it is a response to it. Our work is also speculative, and it is a subjective interpretation of the landscape. We are interested in the traditional methods, but we also want to inject our own perspectives into the discourse. I think the landscape and our urban environments are so much more entangled and dynamic than they once were, so it feels natural that they are interpreted and represented differently.

Yes, I felt that through the dissonance of the music which seemed to reimagine the harmonious romantic way landscapes were portrayed traditionally.

I: Yeah, I think this is what is interesting about Alex’s practice. He works a lot with dissonant sounds and polyrhythms which, in the context of landscape depiction, challenges the rules and orders the classical representation of landscapes present. Especially as many landscapes we know today have been established through classical painting and music.

Credits

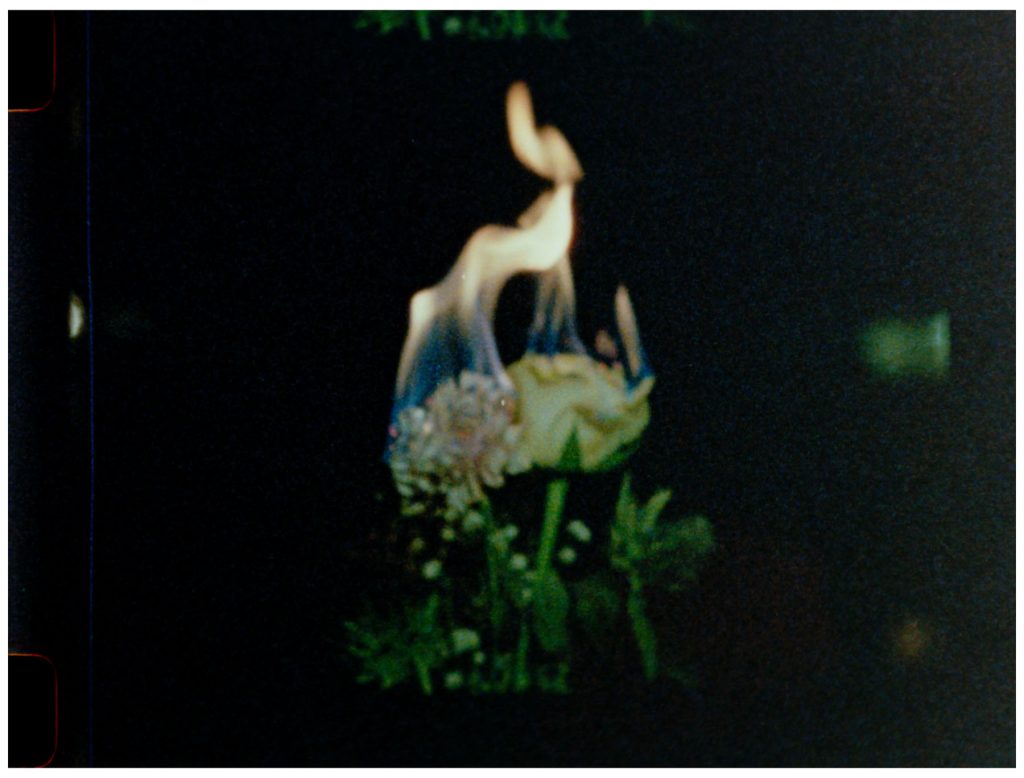

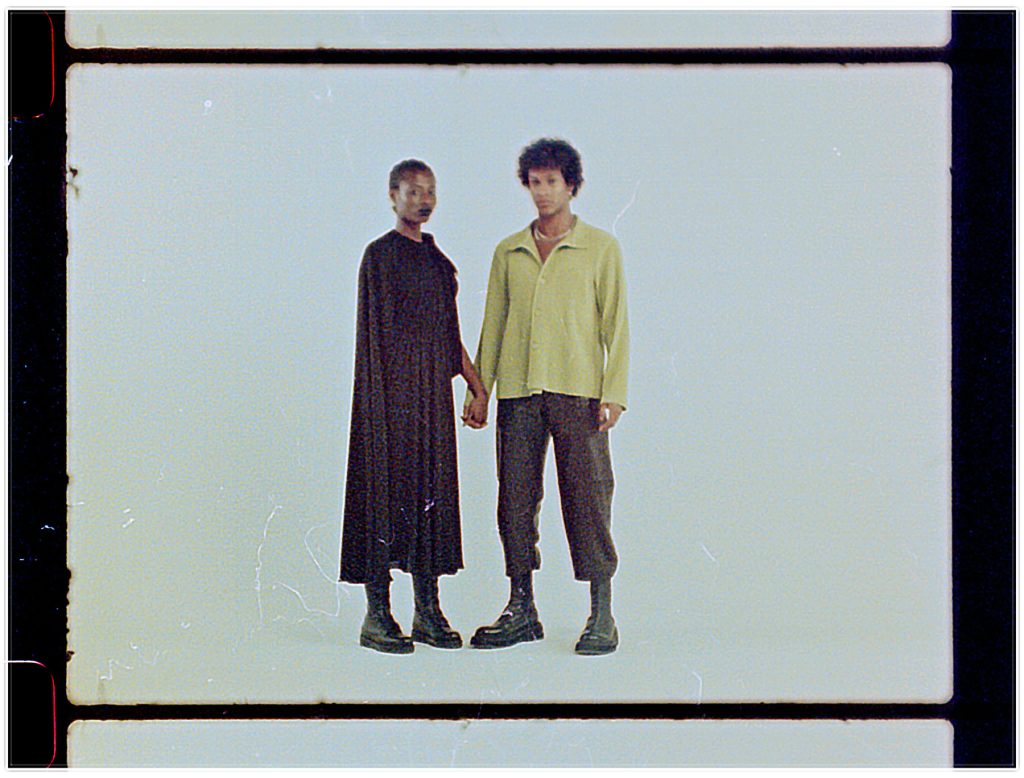

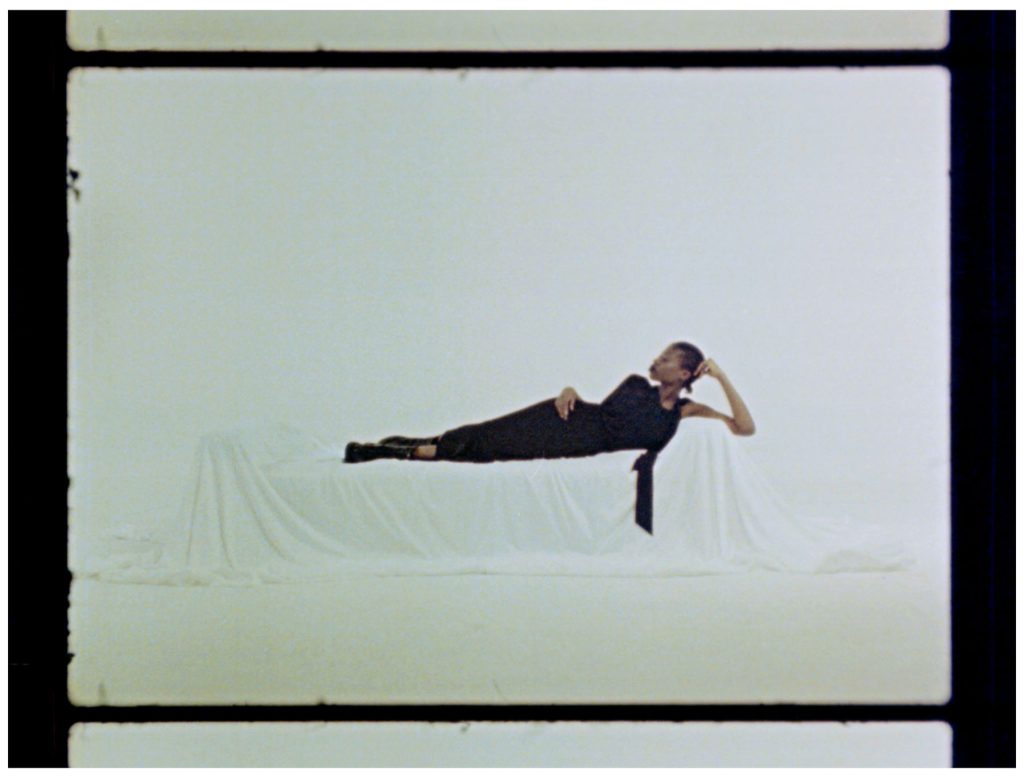

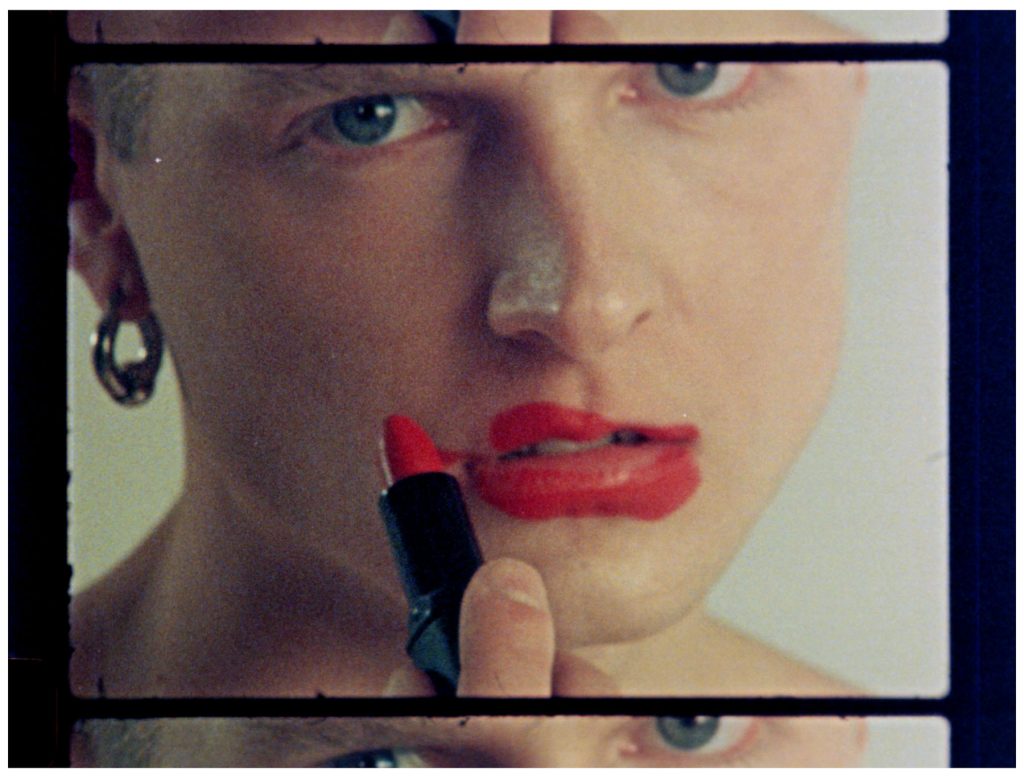

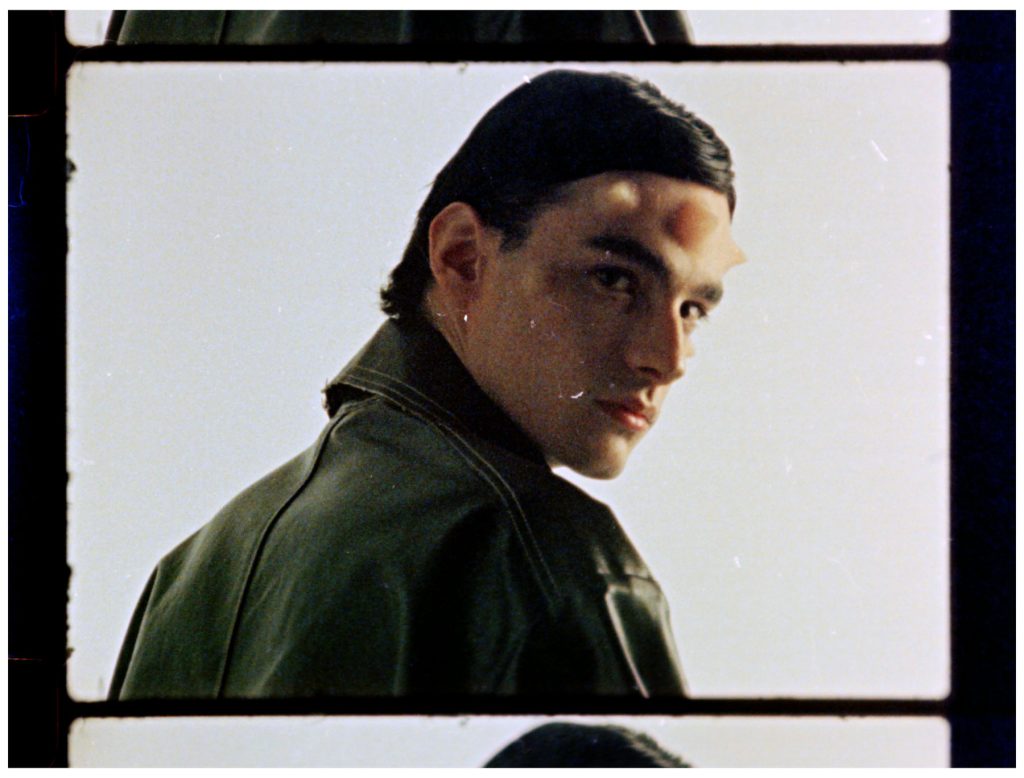

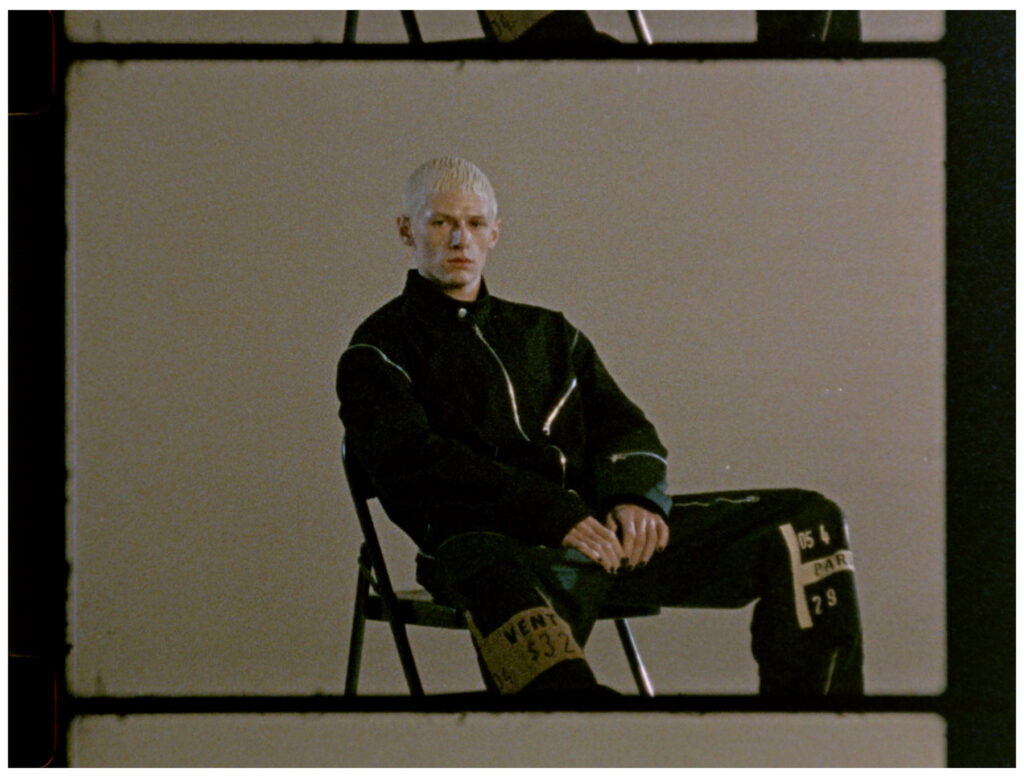

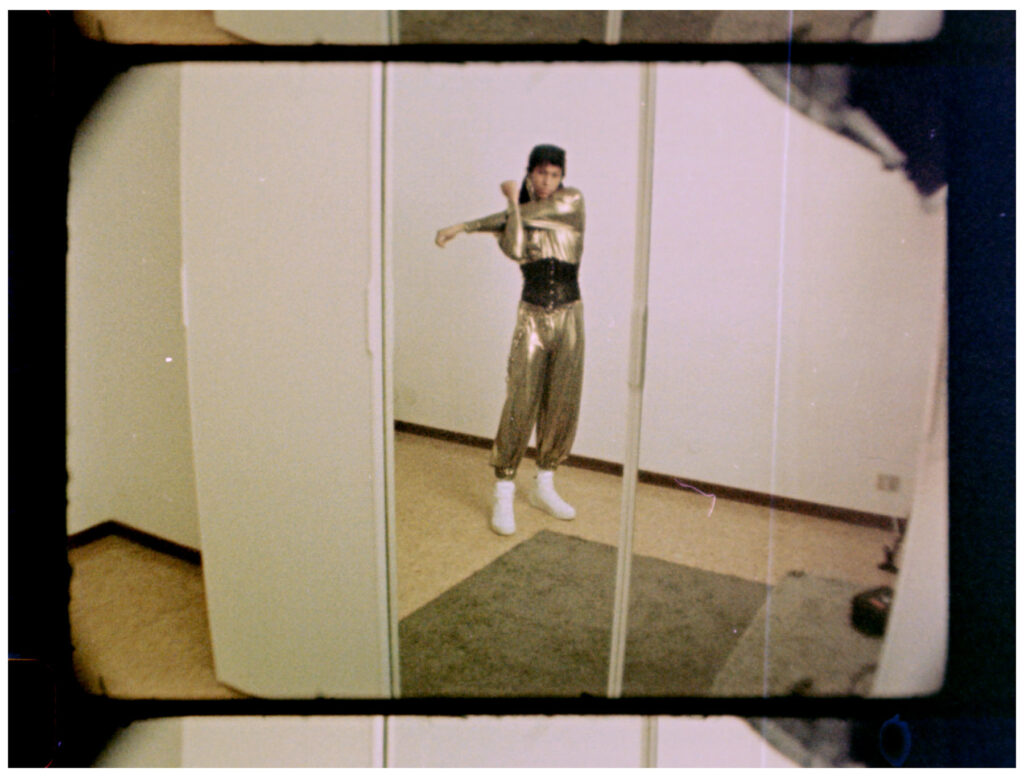

Silt Stills. Courtesy of the artists.

Order ‘silt ost’ here