“Alec Soth does wander but he does it in a territory that he knows best”

When you think of an exhibition from a world-famous photographer, it would not be unusual to assume it would be located in a big city known for its rich cultural heritage such as London, Tokyo or New York. Certainly, your mind would not immediately go to a tiny green island between England and France. But Guernsey, which is part of the Channel Islands, is where you can find photographer Alec Soth’s exhibition Looking For Love.

Of course, this is not the first time a big name has been associated with the island, it was the home of exiled Victor Hugo and inspiration for his book The Toilers of the Sea. There are several paintings by Renoir of the rocky coves and caves of the southern cliffs. In addition to this, the Channel Islands were the only part of Great Britain that was occupied by German forces during World War II and this history inspired the best selling novel and subsequent film adaptation The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Society.

In recent years the island has also become known for its photography festival involving well-known photographers such as Martin Parr CBE and Mark Power. Now the Guernsey Photography Festival welcomes Alec Soth to that list for its ten year (plus one due to delays caused by the pandemic) anniversary.

Alec Soth is an American photographer who was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He gained fame for his colour photographs which he takes on a large-format camera. His work has been described as being based in the ‘documentary style’ and much of it consists of the people and landscapes in the rural and suburban American Midwest and South.

This particular exhibition of Soth’s work ‘Looking for Love’ consists of earlier works of his, taken before the projects which propelled him into the spotlight of the art world. NR Magazine was joined by Jean-Christophe Godet who is the Artistic Director of the Guernsey Photography Festival and the curator of ‘Looking for Love’ at Guernsey Museum at Candie.

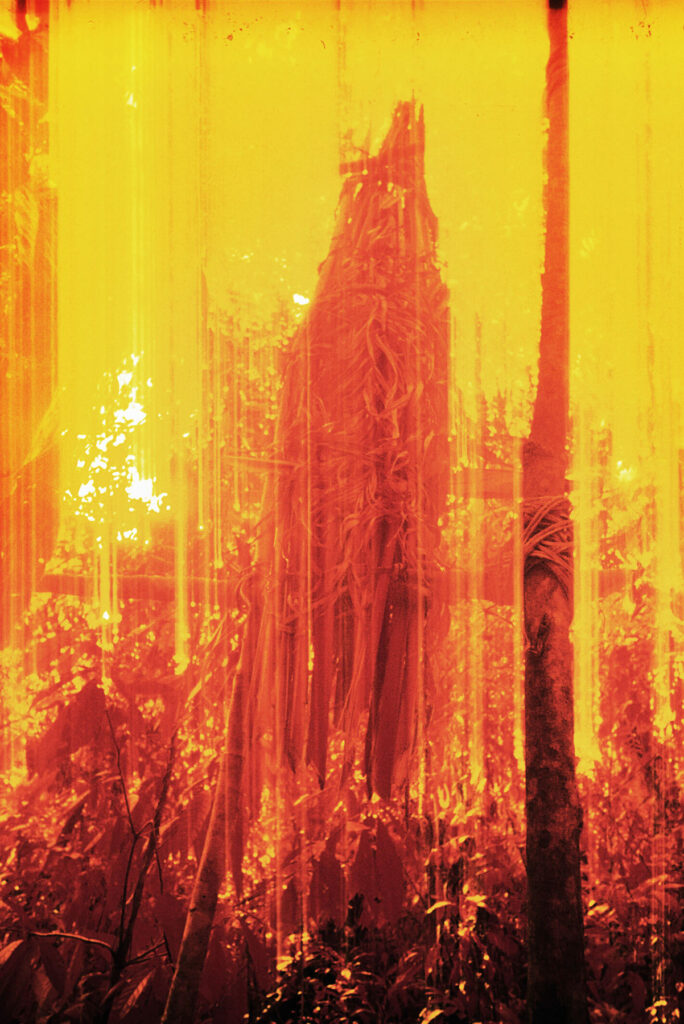

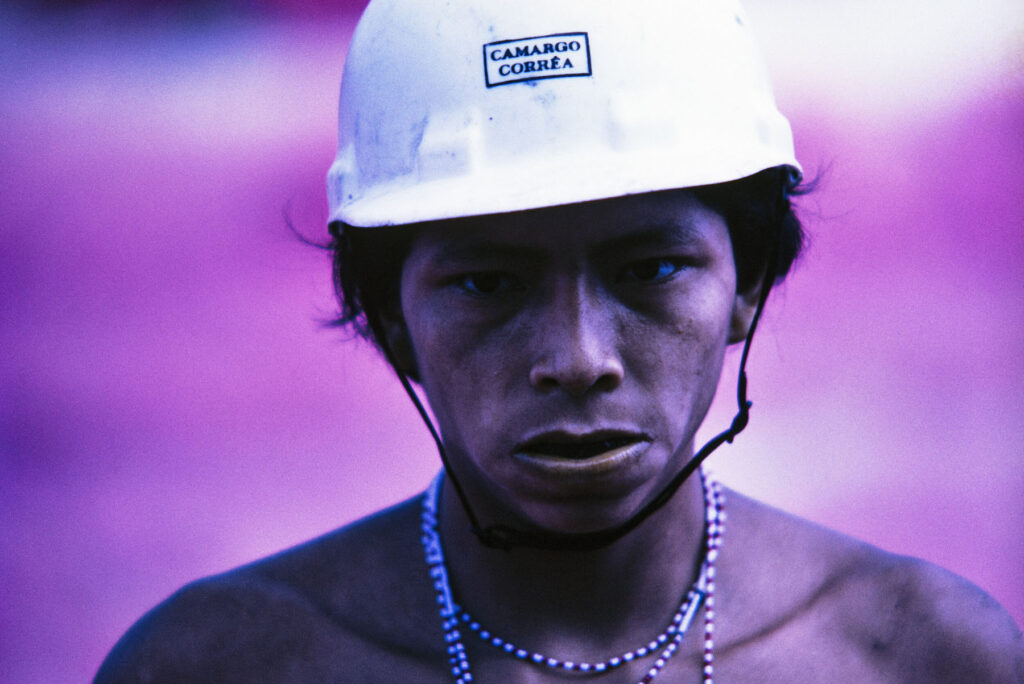

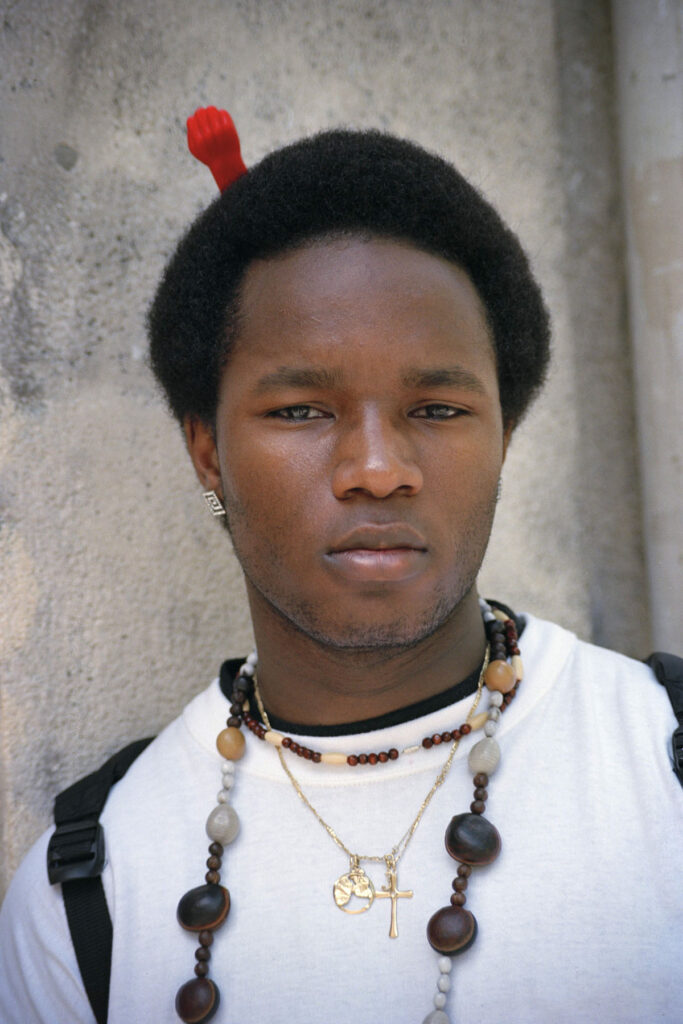

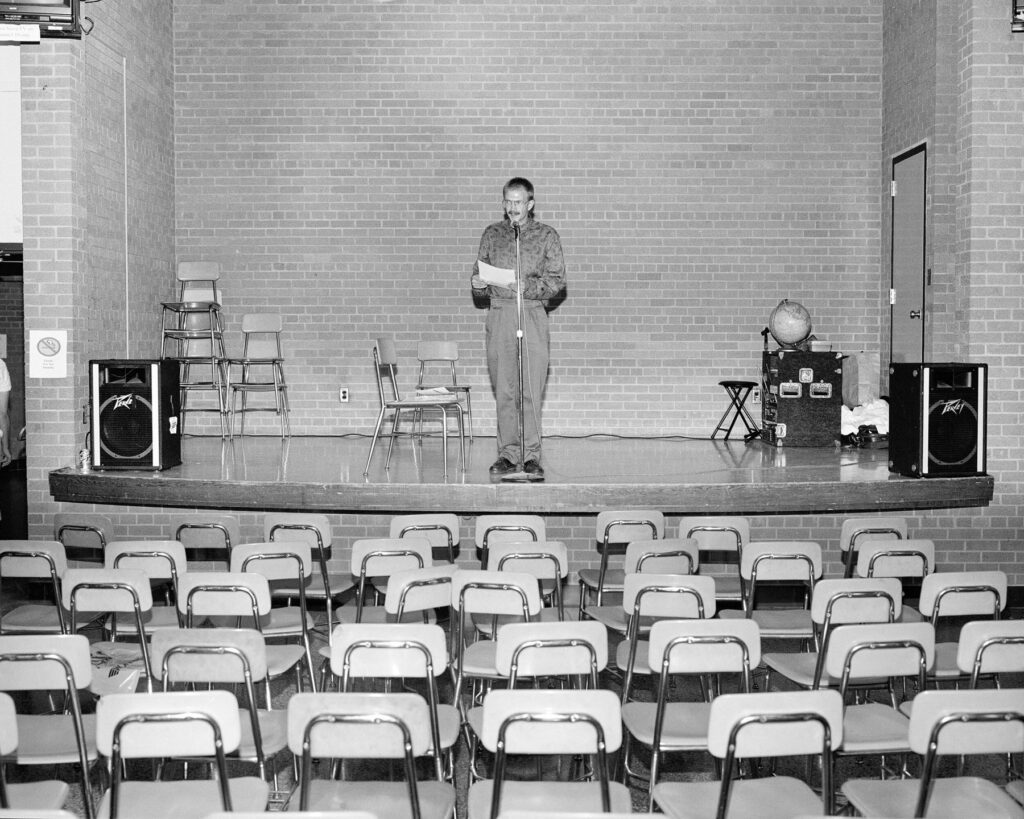

Upon entering the gallery one is greeted by a sea of black and white photographs of people with a few landscapes dotted in here and there. The introduction on the wall tells us, in Soth’s own words, about the time in his life that the pictures were taken. Jean-Christophe Godet expands on that text. “People think this exhibition is one project but it isn’t, it’s a collection of projects. This was a time when he was quite young and feeling miserable, as we all do when we are young. He didn’t know what he wanted to do with his future but was still interested in photography. His job at that time was to work in a photo lab where he processed all the films. In the evening he would go to bars, and meet people and take their photographs. At this stage, he was in a learning process. That’s why we were interested in this exhibition because we wanted people to know where Alec Soth came from.”

The photographs in this exhibition were not taken on a large-format camera like much of Soth’s work, Godet explains, but on medium-format. “The next projects he did, which is what he became famous for, that’s when he started shooting on large-format with the big camera. He likes taking his time when he shoots people, so setting up the camera gives him a chance to meet and talk with the people. It helps him relax as well because he’s an introverted person. He’s the type of guy, if you sit next to him on a plane, he won’t talk to you. He learned how to be more social from doing this exhibition.”

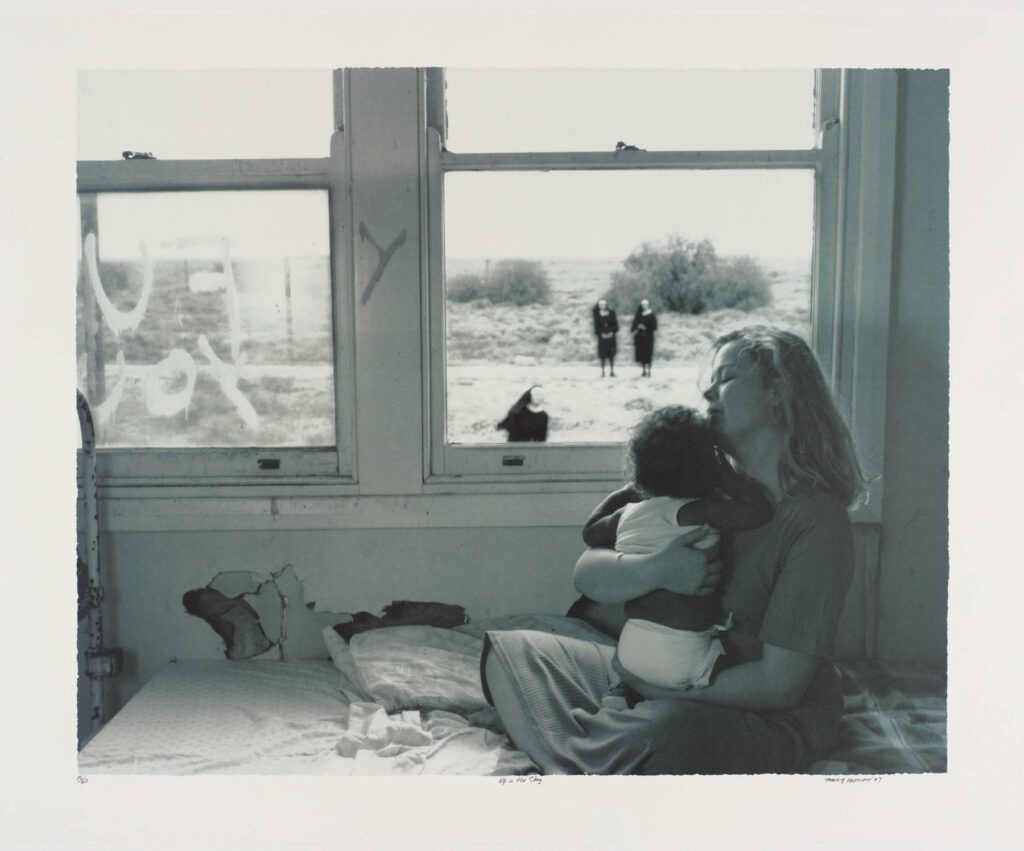

Godet walks over to a pair of photographs, “There’s no story in this exhibition. Soth liked that, it’s up to you to decide the story of the characters you are going to meet. From a curatorial aspect, I wanted people to be able to infer their own meaning onto each picture, but also at the same time some pictures work together to tell a story.”

He points at the duologly, “For example, I decided as a curator to put these two pictures together. The two middle-aged men in one picture appear to be looking at the young girl in the other, who seems to be flirting with a boy. You question who the girl is and if that’s her boyfriend? Then when you put the two pictures together you question if the two old guys are at the same party? Are they perverts or are they nostalgic about the time when they are younger?”

Godet gestures to the rest of the exhibition enthusiastically “There’s no information about these images because Soth is more interested in human nature. He’s not a documentary photographer, he’s not telling the story of the people in a town in Midwest America, it’s more about understanding feelings and emotions. He wants you to decide the story behind them. He wants you to imply your own experiences onto them.”

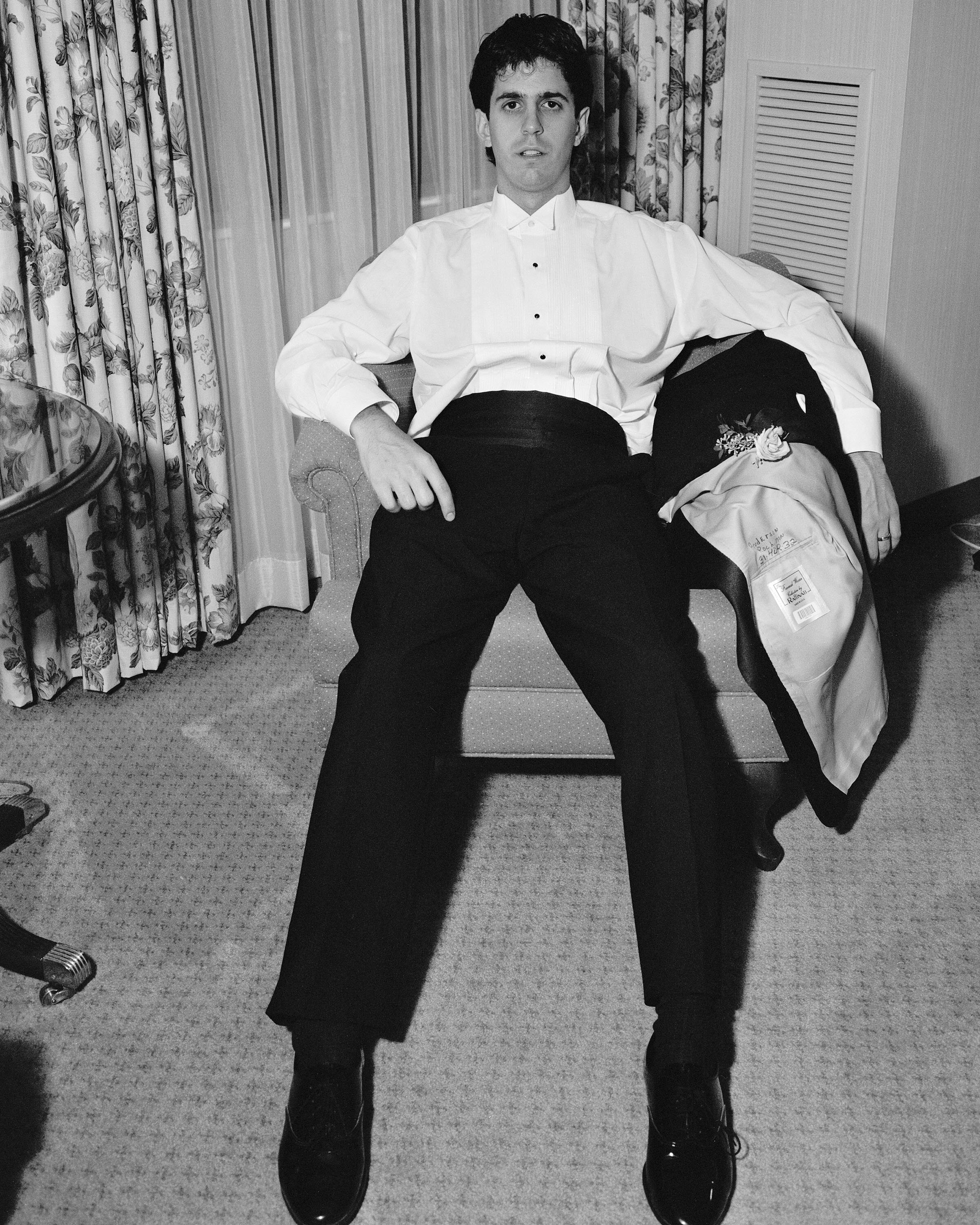

He leads me to another image, this one of a young man in a suit, easily missed in the sea of photographs. “This is Alex Soth’s self-portrait. He took it the night before he was getting married. He looks quite relaxed, maybe half drunk and he looks like he is feeling quite satisfied with himself. There is something there that he is trying to tell us because his work is always about him as well, it’s about the way he feels and relates to the world. At the beginning of the exhibition, we are told that he is miserable and alone but now we discover that at some point during this project, looking at people looking for love, he found his love, in some way, by getting married. But it’s up to us to decide how we think he is feeling about this.”

Godet beckons me to the centre of the room. “In this central part of the exhibition, we changed the tone so it looks like it could be the inside of a bar or a club. In this section I was able to put three generations of three different women telling their own story. The young teenager clinging to her lover, the middle-aged women on her own in a bar looking strong but also a bit lonely, and finally the glamorous old lady with her cocktail. I love how, with Alec Soth, you can connect these together. This exhibition is about loneliness and searching, about feeling disappointed and neglected but also hope. Overall it’s kind of dark and lonely because that’s how he felt at the time, but there are plenty of layers. For me, I think that’s how he became famous because he reaches us with his human emotions which is universal.”

He continues walking around the exhibition. “He’s not trying to impose anything on us, by saying ‘oh look how beautiful that is’ or ‘I’m going to show you what love is’, it’s up to us to integrate the raw human emotions he has. You need to take your time to absorb the photos, it’s not like the Wildlife Photography of the Year exhibition. It’s not like ‘oh that shot is spectacular’, and then you forget it when you move onto the next one. With Soth’s work, it’s like you suddenly slow down and you really appreciate how much is in each photo. The images are so strong they stay in your mind for a very long time.”

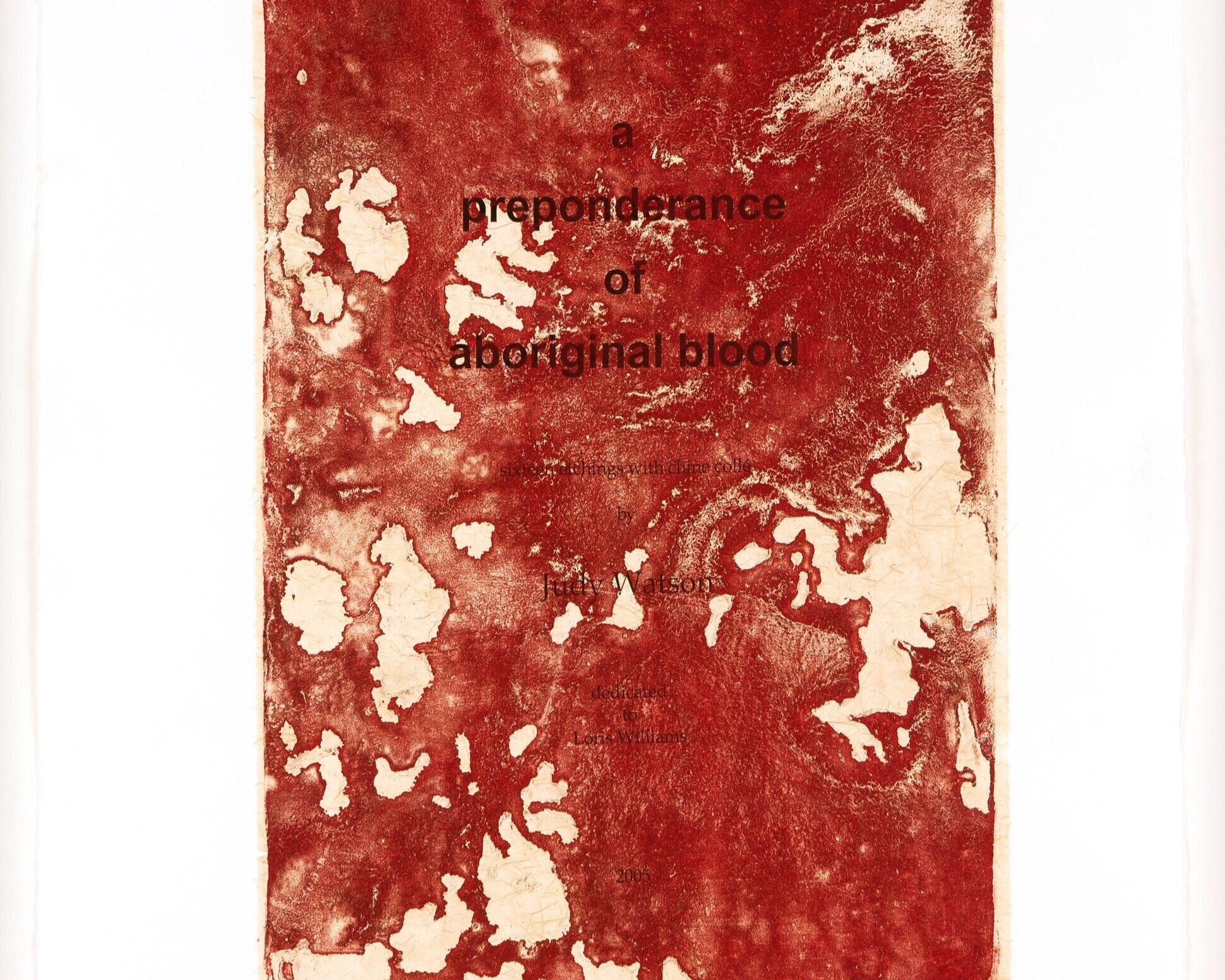

Back near the start of the entrance, he points at one image which has been blown up to cover an entire section of the wall. Against a snowy backdrop is a billboard upon which is a personal ad titled ‘Looking for Love’. It’s one of the few texts to be found in the exhibition, a deliberate choice Godet explains. “Soth is a massive reader of poetry, but he doesn’t like associating the two because he says poetry and photography tend to reject each other and I understand why he says that, because there’s already so much poetry in his photo he doesn’t need more.”

“But what is the difference between Soth’s work and the images of everyday life you can find on social media?” I ponder.

Godet tells me that, “I would say Fine Art photography makes you think. That’s why the Guernsey Photography Festival focuses on contemporary photography and fine art photography because you reach a different level. Everybody says it’s quite easy to take a photo and that’s true. We have the technology to take a good photo readily at hand, but for example, if you take a photo of the sunset on one of Guernsey’s popular beaches like Cobo.” He gestures dismissively, “‘Wow great photo’. The problem is those photos will be distributed on the net and there will be a million photos of Cobo and the sunset and they all look the same. They all look pretty in terms of colour and they have the wow factor but then you forget them. Because we have been oversaturated by them. It’s like reading a good book, when you read a good book it stays with you for a very long time and the reason it stays is because it triggers emotions within you and makes you think about life, your own and others, and that’s where the difference lies.”

Curious, I ask Godet how Soth came to be a part of the Guernsey Photography Festival. He is only happy to tell us the story and talk more about both Soth’s art practice and personality.

“I met him in Paris seven years ago when I introduced him to the idea of coming to Guernsey. At the time I remember he said, “What?” and I said, “Guernsey…”, “Where is that?” And I said “Oh it’s a small rock in the middle between France and England’ and he started laughing about it. I think he didn’t take me seriously because at the time we were just starting the Guernsey Photography Festival and we were not well established like we are now.

But then word started spreading internationally that there was something quite interesting developing in Guernsey for photography and also we had Martin Parkin and Mark Power come over. Mark Power is a good friend of Alec Soth and all those people were our best ambassadors and they were saying “Oh yeah I’ve been to Guernsey, I’ve met Chris and the team there and it’s been a fantastic experience, it’s a great festival” so slowly we gained a good reputation.

So I met him in Paris again for another big photography festival, and he recognised me and I told him that we were going to celebrate our ten year anniversary. And he said, “Oh yes I’ve heard about your festival now and I’ve been told good things.” He was supposed to come last year but unfortunately, because of the pandemic, he couldn’t make it.

In my opinion, he is one of the biggest names you can get in the world of contemporary fine art photography so the moral of the story is never give up. But he’s a really nice guy, intelligent and modest as well. There’s nothing pretentious about his work. Everything is coherent with Alec Soth. When he takes a landscape, every single detail in that photo has some kind of significance. And it’s all about what he know’s best, which is America. Soth has never been a travel photographer, there is this myth about being a photographer that you travel a lot that you travel the world, the lifestyle of freedom and wandering the world. Alec Soth does wander but he does it in a territory that he knows best. All his personal work has been related to the midwest of America. I love that about him because what’s the point of sending a photographer to say the Middle East when they don’t know anything about the culture. It’s much better to ask someone local to take the photos and give us the reality of things.”

Speaking of keeping things local, “Do you think Guernsey has the potential to become a big cultural hub of photography and Fine Art?” I ask him.

He laughs, “I’ve been working on that for the last ten years. I do believe there is potential there, but I think to reach that there is a necessity for a political drive for cultural development. I think unless we reach an agreement on a political level there will always be a bit of a struggle. Because if you want to be a cultural hub you need to invest in it. You can’t just rely on a small amount of public funding and donation and sponsorship. I’ve worked on lots of different major projects in major cities and you need funding for it. With the Guernsey Photography Festival, we have tried our best and we have proven it is possible, but I think a political position is necessary. I think there is a tendency in Guernsey to be satisfied with what we have, and while I don’t criticise that, there is so much more in the world to discover in terms of the profile you can create. It’s important to help and support local artists, but I think if we want to attract people to come to Guernsey as a hub local artist won’t be sufficient. You need to have big names like Alec Soth. Then people hear about it and think ‘oh wow this is pretty cool place to visit and live, not only can you enjoy the beaches and wildlife and historical culture but you have names like Alec Soth as well.’”

Before he leaves I ask a final question, “What are the plans for the future of the photography festival.”

“This is just the starting exhibition for this years festival,” Godet tells me, “because on the 23rd of September we are having a big open night for the Guernsey Photography Festival with the Guernsey symphony orchestra and we will have a multitude of international artists. I think in total we have 25 exhibitions planned in celebration of our ten year (plus one) anniversary. We have some really exciting artists but I’m not going to mention any names, you will have to wait for the press release, but it’s going to be big!”

Later, as I walk away from the museum I think over Soth’s work exploring the beauty and complexity of the mundane and Godet’s thoughts on the need for local governments involvement in local culture. Lost in thought I stumble on another small outdoor exhibition of different photographers work, about ten minutes walk from the gallery. It’s concise and wonderfully accessible to the public. It reminds me that Soth’s most famous work was created in the region he was born. With the pandemic making us rethink travel, perhaps it’s time to look away from larger cities and instead demand for art and culture to also be brought to, and created in, our own tiny pockets of the world. Something the Guernsey Photography Festival has already been doing for ten (plus one) years.

Credits

Find out more about the exhibition on www.museums.gov.gg

Images · ALEC SOTH

www.alecsoth.com/