Vincenzo De Cotiis: Navigating the Intersection of Analysis and Experimentation in Architecture and Art

Vincenzo De Cotiis, an architect and artist from Milan, Italy, has built a career that blends the past and future through his unique design philosophy. After studying at the Politecnico di Milano, he founded his studio in Milan, which serves as both his home and the center of his creative work. De Cotiis’ designs result from continuous analysis and experimentation, merging space and time, cultural layers, and unexpected leaps. His projects, though complex, are powerfully expressed through their materials.

Your architectural philosophy is deeply rooted in a continuous process of analysis and experimentation. Can you elaborate on how this approach shapes your work?

My work is an ongoing dialogue between analysis and experimentation, where each project is a journey through layers of cultural and temporal significance. This process allows me to create spaces that resonate with history while embracing future possibilities. By continuously challenging conventional boundaries, I strive to evoke emotional responses through the interplay of materials and forms.

How do you select the materials for your projects, and what role do they play in your creative process?

Materials are chosen for their ability to convey stories and emotions. Each project requires careful consideration of how each material can contribute to the overall experience. I do not limit myself to a fixed list of materials but allow the concept and context of each project to guide my choices. This flexible approach enables me to explore new possibilities and create unique designs.

Your studio in Milan is the heart of your creative endeavors. How does the city itself influence your work?

Milan’s rich cultural heritage and dynamic contemporary scene provide a constant source of inspiration. The city’s architecture, art, and vibrant design community encourage me to blend traditional craftsmanship with innovative techniques. This fusion of old and new is reflected in my work, creating pieces that are both rooted in history and forward-looking.

If I asked you to take me to a place in Milan that holds special significance for you, where would it be and why?

I would take you to the Brera district, which is a hub of artistic and cultural activity. The juxtaposition of historic buildings with modern galleries and studios embodies the essence of Milanese creativity. It’s a place where tradition and innovation coexist harmoniously, much like in my own work.

Your work often balances between the future and the past. How do you achieve this equilibrium in your designs?

Achieving balance involves a deep respect for the past while being open to future innovations. I draw inspiration from historical contexts and reinterpret them through a contemporary lens. This approach allows me to create designs that are timeless yet progressive, embodying a sense of continuity and evolution.

Can you give us an example of a project where materiality played a crucial role in shaping the design?

It is difficult to choose a single series, as all my projects hold deep importance for me, and each explores materiality in unique ways. Every project is an intellectual exploration of how materials can interact and transform each other. In every work, I seek to discover the intrinsic properties of the materials and bring out their expressive potential, creating a dialogue between material and form that transcends time and space.

Your work often involves unexpected interactions within spaces. How do you approach creating these unique experiences

Creating unique spatial experiences involves a meticulous process of layering different elements to provoke curiosity and engagement. I aim to disrupt conventional expectations by integrating unexpected materials, forms, and textures, encouraging viewers to explore and interact with the space in new and meaningful ways.

What are some of the intellectual and artistic challenges you face in your design process?

One of the primary challenges is maintaining a balance between artistic expression and functional design. While my work leans heavily towards sculptural and conceptual art, it must also serve practical purposes. Navigating this dichotomy requires continuous experimentation and refinement to ensure that both aspects coexist harmoniously.

Looking ahead, what directions or projects are you excited to explore in the future?

I have a profound appreciation and understanding of the history of art, which deeply influences my work. Each of my series is rich with references to the past, yet my aim is always to reinterpret these elements in a contemporary way. I am excited to continue this exploration, blending historical influences with contemporary art principles to create innovative and timeless pieces. I am particularly enthusiastic about projects that allow me to delve deeper into this fusion, bringing forth new and unique interpretations that resonate with today’s discerning audience.

In order of appearance

- Vincenzo De Cotiis Foundation. Photography Wichmann + Bendtsen. Courtesy of Vincenzo de Cotiis Foundation.

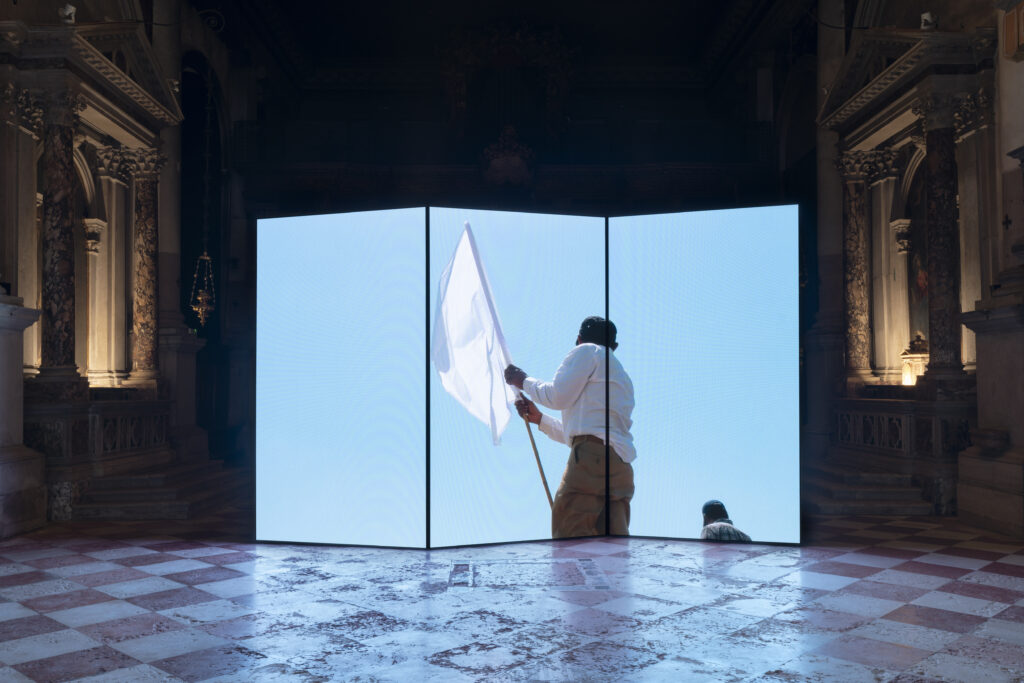

- Vincenzo De Cotiis. Installation View, Archaeology of Consciousness Exhibition, Venice. 19 April – 24 November 2024. Photography Wichmann + Bendtsen. Courtesy of Vincenzo de Cotiis Foundation.

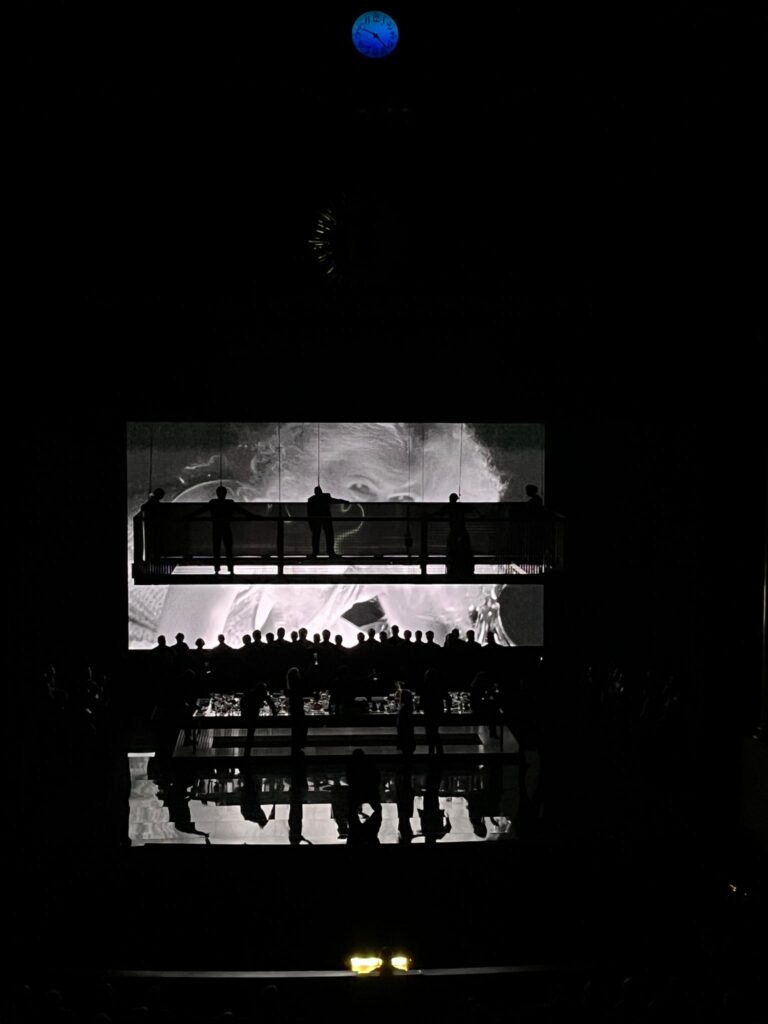

- Vincenzo De Cotiis Foundation. Photography Wichmann + Bendtsen. Courtesy of Vincenzo de Cotiis Foundation.

- Vincenzo De Cotiis Foundation. Photography Wichmann + Bendtsen. Courtesy of Vincenzo de Cotiis Foundation.

- Vincenzo De Cotiis, DC2316 VENICE, 2023. Hand-painted recycled fiberglass, German silver, fabric. Courtesy of Vincenzo de Cotiis Foundation.

- Vincenzo De Cotiis, DC2310 VENICE, 2023. Hand-painted recycled fiberglass, Murano cast glass, German silver. Courtesy of Vincenzo de Cotiis Foundation.

- Vincenzo De Cotiis, DC2312 VENICE, 2023. Blown Murano glass, cast brass. Courtesy of Vincenzo de Cotiis Foundation.