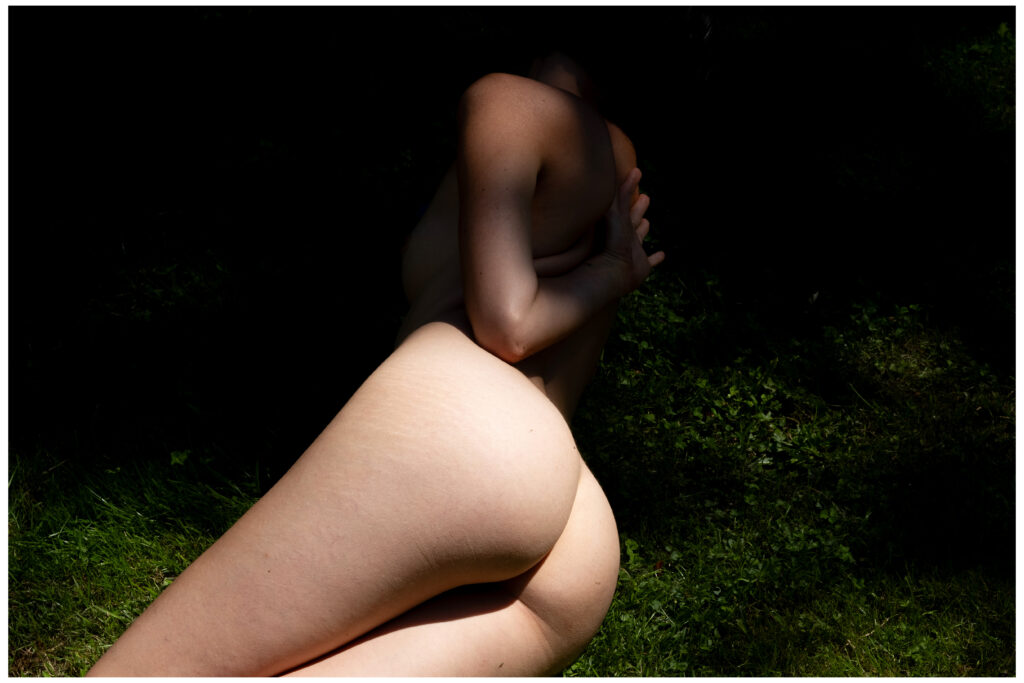

En Plein Air

Team

Photographer · Sara Pavan

Art Director · Flavio Crespi

Styling Assistant · Giovanni Tricase

Supported by FUJIFILM, Shot with FUJIFILM GFX100S

Team

Photographer · Sara Pavan

Art Director · Flavio Crespi

Styling Assistant · Giovanni Tricase

Supported by FUJIFILM, Shot with FUJIFILM GFX100S

The mountainous village of Vals is blessed by the grace of natural wonders. Rising above sea level in the Canton of Grisons, the Swiss idyllic refuge is home to thermal waters dubbed healing hot springs, their history dating back to the 17th century. Here once lay a sanatorium transformed into a spa hotel in 1964, brought about by the physicians marveling at the curing properties of the springs in the 19th century.

The entrance of the spa hotel ushered in a shift from medical tourism to leisure travel within the neighborhood, all the while retaining the suggestion of a place for alternative healing methods. In 1983, the municipality of Vals reigned over the hotel compound and tapped architect Peter Zumthor, a Grisons native, to architect a new structure to house the thermal baths. The mineralized water of the St. Peter spring had been luring in bathers for more than a century, but Zumthor’s architectural masterpiece for the thermal water’s new home further ushered the territory as a sought-after getaway.

He built a monolithic building made of raw concrete and 60,000 slabs of Vals quartzite, a nod to the archaic beauty of the Vals Valley, and divided the baths into six pools, spanning between 14°C and 42°C pools. Here, the stone architecture and the lush natural land enclosing it form a visual and spiritual harmony. From then on, the architectural community of Vals grew, forming an ensemble of sought-after hospitality and structures backed by the minds and craftsmanship of some of the most revered architects today.

Two years after the opening of Zumthor’s thermal baths in 1996, his masterpiece and the hot springs were honored a status of protected heritage. Yet as years went by, the surging demands of more sophisticated travel and tourism urged the community of Vals to burst forth from its cocoon. Avant-garde buildings began to appear, crafted under the hands of celebrated architects, namely Tadao Ando, Kengo Kuma, and Thom Mayne. Their presence has pronounced Vals as a haven of sojourn that welcomes guests to dip their toes in its remedial mineral springs and luxuriate in one of the world-class accommodations surrounded by the meandering hills, fragrant fields, lengthy hiking trails, and snow-capped ski slopes.

7132 House of Architects suits the name it was given. Tadao Ando and Kengo Kuma bring in the influences of their Japanese roots as they both steep the rooms they designed in the design ethos and lifestyle of their homeland. Ando pays homage to the subtle aesthetics of Japan’s tea houses when designing his 18 rooms and bathes each space with a transition between wooden panels and slabs. His balcony windows offer unobstructed views of the alpine scenery from the mountainside across the room, and his minimal use of furniture, other than a bed taking up most of the space and a wooden bedside table, distills any kind of clutter and distraction.

Similar to his compatriot, Kuma employs the tranquil aura of wood to envelope his 23 rooms in a sensation of cozy oakwood cocoons. He layers the modern Swiss oak panels, one slightly on top of the other, until it forms what may resemble dragon scales that make up the walls and ceilings. Continuity threads Kuma’s design. He places a lengthy slab of wood beside the bed which extends to the bathroom and where the basin and faucet are set upon. Here, openness follows as Kuma veers off from closing up the space and opts for an open floor-level shower with clear glass casing and a base of local granite. Showering means the guest affords a view of the bed and the abundant grove peering through generous windows.

When Thom Mayne’s design emerges, a sudden shift takes place. The architect, who designed 22 rooms, turns to wood for some of the spaces and black stone for the rest. He plays with the two materials, often letting the other win while ensuring they complement each other. In his wood-winning rooms, a sculptural free-standing shower stall stands at the center of the space, an attempt by Mayne to immerse the guests in a three-dimensional experience of space. Its lifesize, stone-like architecture is corralled with a luminous, milky film to enable the guest to see the outside from the inside. Stepping into Mayne’s Stone rooms, Vals quartzite creates a cinematic ambiance, occasionally interfered with by the warm glow of light concealed behind the walls and the lemon-yellow enclosure of the shower stall.

From thermal baths to hotel rooms, Peter Zumthor exhibits a sensuous journey physically and emotionally. His ten rooms are distinctive from his collaborators as he infused each space in stucco lustro, a plastering technique from the Italian Renaissance that produces light-reflective gloss and likens to the surface of marble. He selects a spectrum of zesty and introspective hues, swinging from lush red and vibrant yellow to illusory black, and melds everything with handpainted curtains made of Habotai silk. Luxury at work effortlessly infiltrates the rooms, coupled with the chandelier wrapped in what may be globe-carved stones.

7132 House of Architects is an idle passageway to the entire 7132 dreamscapes. Before reaching 7132 Thermal Baths, guests may pad through 7132 Hotel 5S whose three penthouse suits on its top floor were also designed by Kengo Kuma. Inside the hotel, rare natural materials like wood dominate the landscape, forming a harmonious balance with the scenic grassland sitting outside the property. In another path, guests are led to the chalet of 7132 Glenner, an adjoining accommodation, which sits at the center of the village. Its traditional Swiss design blends well with the modern interior and rooms, an understated guest house brushing against architectural giants within the complex.

It is no longer a myth how Vals gradually received its namesake as a coveted destination and a welcoming respite in the cradle of Swiss nature, from the hotel rooms designed by revered architects to the believed curing property of the hot springs. Even if the guests move away, the lasting impressions 7132 has left them pulls them back in, inviting them to once again return and soak in the wonders of nature and luxury.

When we think of European summers and the festivals that define each month, drenched in sunlight with the heat on our skin, one such festival that joins ranks beside the northern titans like Dekmantel and Glastonbury is Primavera Sound. Initially beginning its legacy in Barcelona in 2001 and now for the first time in Madrid, the festival has become a pioneer in the events space, becoming one of the largest and most-attended festivals in Europe. Boasting headliners such as The xx, Tame Impala, Kendrick Lamar and Patti Smith, but also spotlighting smaller, local artists, it’s a place where creatives big and small come together and revel in the Barcelona heat.

With a focus on gender equality and their role in the sustainability of the location, this year’s Primavera Madrid debut is an opportunity to reexamine their track record of eco-conscious achievements and active gender equality efforts. In this interview, I chat with festival curator Joan Pons about the music scenes of Spain, TikTok-era festival etiquette and the broader subjects of inclusivity and sustainability at Primavera.

Is there a specific moment in time or influence from the music or creative scene that inspired you to get into the curation game? Were you an experienced raver or partygoer all along, or rather somebody more behind the scenes?

Of course. We have always explained (almost taking on legendary dimensions) that the idea of the festival was born from four friends, who at the beginning of the century wanted to bring the alternative and electronic music artists of that time who were not touring in our country. We believe that this initial idea remains: we still consider ourselves music fans and we still want to bring our favourite artists of our present to our home. More than a raver, personally, I consider myself what I said before: a music fan who has been to many festivals, of very different music styles and each one of them is enjoyed in a different way. Some are for dancing, others for sitting and relaxing, others for a singalong, others to surprise you and others to provoke new sensations. I think Primavera Sound, in the end, is a festival where you can find all these kinds of possibilities. In other words, we have made the festival in our own image and likeness.

When considering the rave and music scenes, Madrid and Barcelona might not immediately spring to mind for many. What is it about these cities, specifically the Spanish and Catalan music scene, that might draw more people to these places to rave? Is there a stark difference between the two?

I would like to politely disagree with the apriorism from which this question arises: Barcelona and Madrid are two cities that, at least in this century, have been very important places on the map through which almost all relevant artists and tours have passed. Proof of this is our own history – if we did a festival, it was because there was demand from the public, artists and industry. Also, international interest – for years now, more than 50% of our audience has been from abroad, and 30% from the UK. So we understand that if you say Barcelona, for some people, the first thing that will come to mind will probably be the football team, but for music fans or those with cultural interests, it will probably be Primavera Sound. Obviously, this cultural vibrancy and musical life make cities a hotbed of club scenes, concert halls, music scenes and important artists. Some of them were maybe born around the festival, performing their first steps and finally being headliners, like this year’s Rosalía.

You’ll often see on platforms like TikTok the discussion of festival etiquette, and that many partygoers have ‘forgotten’ how to behave or act respectfully during concerts and events. This was most likely borne out of the Covid lockdown, with a lot of Gen-Z’ers experiencing their first nights out and festivals without the ‘practice’ of partying in their later teens. With Primavera focusing on sustainability and inclusion at its core, how does the festival foster the environment of making people feel free to experience the music in their own way, while also recognising the need for respect and care of the artists and organisers?

The Primavera Sound public is very abundant and diverse, and there will be both aware and escapist people – you can’t tell. What we can say is that the festival is aware and doesn’t want to be a bubble detached from reality, and if some of our gestures, decisions and actions in this sense can help the public that attends the festival to be so too, then that’s perfect. We have done visibility actions and we’ve been involved with both Open Arms and Greenpeace. We also believe that by moving forward on the path of sustainability we are raising awareness among our public (such as the reusable cups, with the almost total elimination of plastics), with tarpaulins explaining the UN programme of 17 sustainable development goals, of which we have been part of since 2019, because the organisation itself made us aware that we were complying with many of them. There are also pioneering initiatives such as Nobody’s Normal, which was born as a protocol to prevent, inform and act in the face of sexual aggression and is now a plan for the promotion of sexual and gender freedom.

Finally, there are our identity decisions, which may seem artistic, and also speak of the reality surrounding us with an inspiring and transforming spirit: the parity poster, increasingly inclusive and diverse because reality is also increasingly inclusive and diverse, not by chance. We believe it is a duty to our time and our reality, and this is what our assistants have told us with very positive feedback that we did not expect after the first year of implementation. They said that they were finally at a festival where they felt free, safe and comfortable to show their sexual identity. So in the end, maybe we do have an aware public.

Primavera boasts a 50/50 gender and pronoun lineup from 2019. With the fact that many bigger industry names feature in Primavera each year, how do curators ensure that smaller artists, some of whom might be LGBTQ+ or gender non-binary, also get the spotlight, as well as financial support? What is the process for research there?

We believe that there is no small print at Primavera Sound and that every name on the line-up matters. If it’s at Primavera, it’s because we love his/her/their music, that’s for starters. Each artist fulfills their function, whether in terms of artistic balance or diversity. The truth is that there is not much mystery in creating an inclusive and gender-balanced line-up, you just have to want to do it – once you have that in mind, it almost works itself out. We also feel that the smaller names actually get the same exposure as the big names because the line-up comes out with all the artists at the same time. They share the spotlight with each other. Also, we create individual assets for each and every one of them and promote all of them equally. It would be disrespectful if that weren’t the case.

I would like to think that this year we have made progress in the gender-balanced lineup, because it’s no longer 50%, and we have taken into account 10-20% of artists who do not identify with a binary separation of gender. We believe that percentage will get higher and higher because, in reality, it will also be higher and higher. If in some way we manage to make this aspect visible through our artistic programming, we can only be proud.

The festivals obviously draw thousands of partygoers each year. In cities like Madrid, where there are issues with heavy tourist flows and the pollution and impact on the local residents that come with it, how does Primavera ensure that the residents of Madrid are not negatively impacted by this large presence of festival-goers?

We believe that our impact on any city that hosts Primavera Sound does not have to be assumed to be negative. In fact, in economic terms, it is highly positive for many sectors (public transport, restaurants, hotels, museums and leisure). In more intangible terms, it brings a cultural value to the life of the city, which during the days of the festival becomes more vibrant and with the eyes of the whole world on it.

On the other hand, we don’t believe, based on our studies and attendance data, that Primavera Sound festival-goers are an annoying type of visitor to the city. In fact, when we talk about it with the institutions of each city, we tend to consider them as cultural tourism.

Primavera has renewed its partnership with the UN Sustainable Development Goals Campaign. With pledges like gender equality and education on the docket, does this alliance inspire Primavera to become a leader in this sustainability and inclusion space – what are you hoping to inspire with this alliance? Do you see yourself as an example in the festival scene?

We like to think that if we are really so insistent on the issue of inclusion and gender equality, it is because Primavera Sound is such a popular festival with so much media attention that we believe in and defend this policy. With this, it can be inspiring for others and ultimately transformative. Whether it really is, I can’t say. But it definitely would NOT be if we didn’t do it. About sustainability – although we received the A Greener Festival award, we know that it is a long road, a process which we will improve little by little. So, if we are an example to anyone, it is to ourselves: each year’s progress should be a benchmark to be beaten in the next edition.

Credits

More info · Primavera Sound Festival Madrid

Special thanks to Chris Cuff (Good Machine PR), Joan Pons and Henry Turner (Good Machine PR)

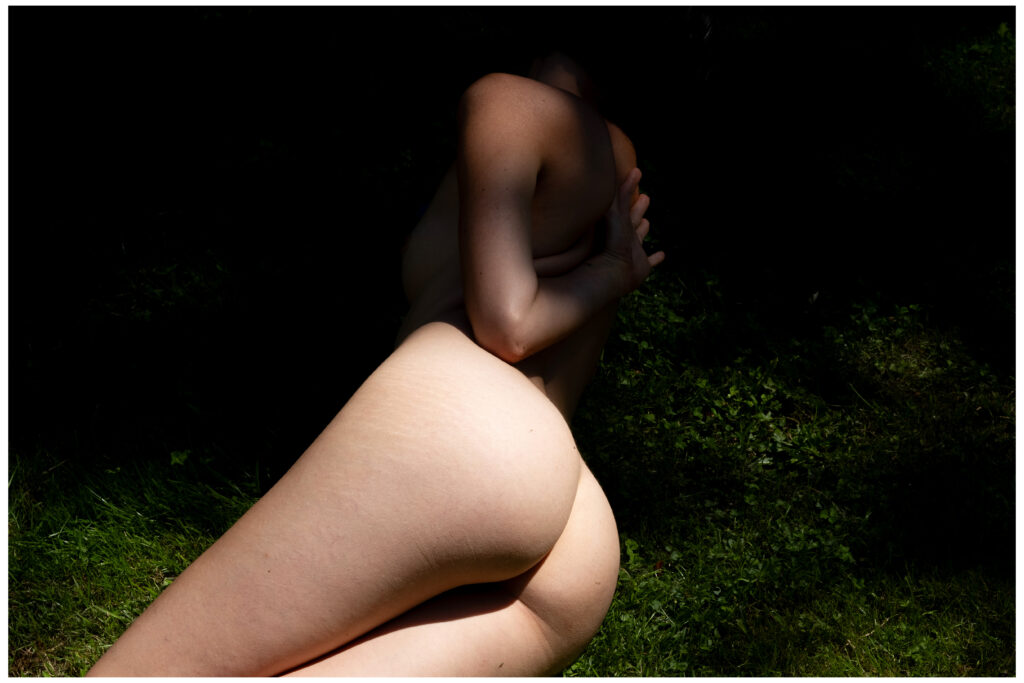

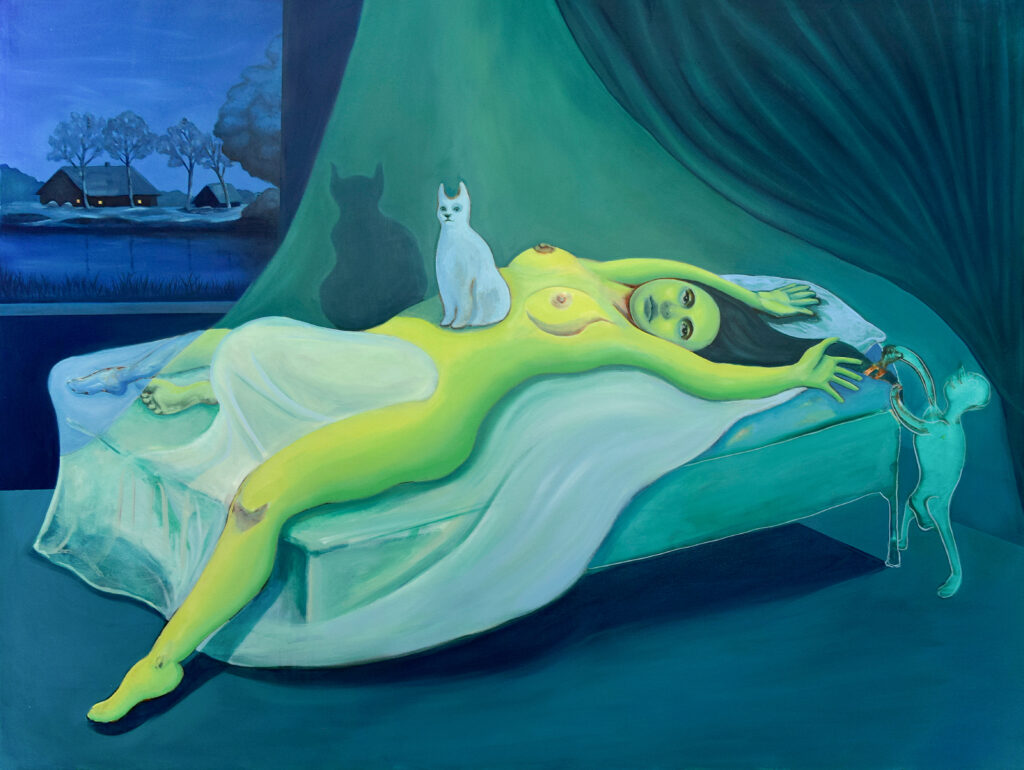

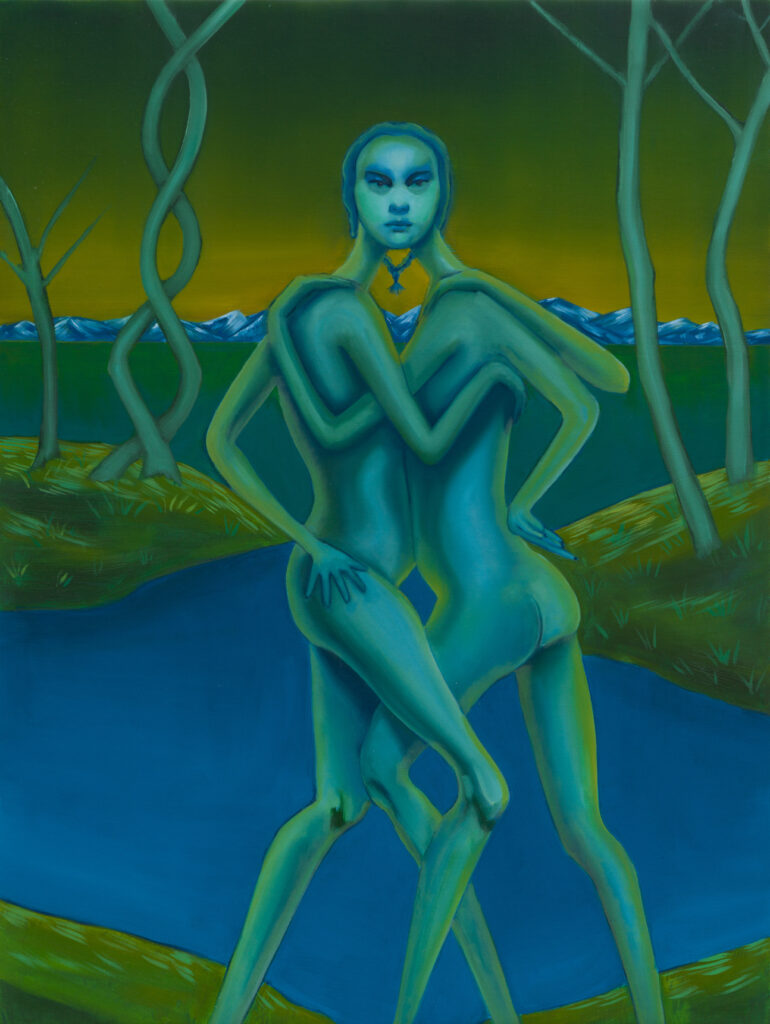

Les Dîners de Mamito, 2022

Bambou Gili’s paintings are world-building projects, sprawling in narrative and unified by rich, tight colour palettes. Throughout her body of work, fantastical landscapes activate the feminine figures inside them, allowing for nature to become an ally, a co-conspirator, a unique character in and of itself. In each series, the artist — whose inspirations range from the animation of Hayao Miyazaki to the French Impressionists — dives into a singular colour spectrum to experiment freely and tap into possibility. Oil drippings in green, blue or purple produce a textural, eerie stillness that moves across tableaux like an omniscient spectre. Gili’s surrealistic scenes, imbued with this energy, are both clandestine and playful: lush plants, serene bodies of water and ethereal trees conceal subjects from one another as their concurrent stories unfold, and each protagonist exudes a presence that matches the magnitude of her surroundings. Within Gili’s alternate universe, environment and human emotion vibrate at an equal frequency somewhere between waking and dreaming.

The Face Stealer’s Pond, 2021

Your paintings deliver an intriguing sense of mystery, a haunting quality,sometimes spectral but in some cases almost ironic. The subjects are oftenwomen portrayed in nature or domestic settings. One particular work or yours, Sleep Paralysis(2021)reminds me of The Nightmare by Heinrich Füssli(1781), while others bare similarities with the secret forests of Rousseau. Beside arthistorical sources, what are the inspirations behind your works? Do you look at peoplefrom your personallife,photographs,magazines,socialmedia?

Yes! Neighbourhood Sleep Paralysis was based off of Nicolai Abildgaard’s Nightmare (1800), after Heinrich Füssli. Regarding inspiration, nothing is off-limits. I tend to gravitate towards working in series. I like to focus on an idea for a long period of time and see what bodies of works come out of it. While I’m doing research for that idea, I scour everything. If I see something that makes me think of the series, I document it and store it in my series folder. So, take my last one — I was looking at imagined scenes from Calvino’s Nonexistent Knight, 14th-century armour from the MET collection, Scooby Doo stills, etc.

Neighborhood Sleep Paralysis, 2020

While looking at your works one can clearly notice the predominance of blue and green, applied both for living figures as for landscapes. Where does this fascination with these tones come from?

Ha! I get this question a lot. Fun fact: In Zulu, ‘blue’ and ‘green’ are the same word. When I go to the MET, I’ll end up staring at a bright green Lisa Yuskavage painting, admiring the use of colour.

In my last solo, The Non-Existent Night, the series started as an exercise to focus on colour at night. A way to consciously limit my palette to greens, blues and purples. That’s not to say I want my next series to focus on these tones exclusively.

Aggie & Pieter, 2022

Talking about light work and how important it is for you, I was reminded of theimpressionists, who often tried to capture the same subject under different light. Can you tell me something about this study of light and how you incorporate it inyour practice?

Light at night is notoriously hard to capture. You don’t often see a true representation of lowlight scenes. Photos and videos often do a bad job portraying those blues. Which is what led to my night series.

I find the dichotomy of timeframes in your work very interesting: on the one hand, the depicted subjects don’t belong to a specific era historically, on the other, they’re located in the specific — and narrow — time frame of the night. How do you look at time when addressing a new series? Is there a straight conceptionoflinearity?

Honestly, I have not thought about it! I think that the red thread here is the fact that all humans have experienced the night.

I had the pleasure of seeing a preview of your new series, which you willexhibit in your next solo show at Night Gallery (LA) in March. Can you explain the inspiration behind it and how you shaped it through paint?

The work is based on, built around Goodbye Earl, a country song by the [Dixie] Chicks. It’s an upbeat tune, just four minutes or so, but as you listen, you’re introduced to an entire saga — two childhood friends grow up together in a rural area. One moves out, the other stays. The one who stays ends up in an abusive relationship and, try as she might to leave, can’t seem to escape. Well, after exhausting legal outlets, she falls back on her old friend, who returns and helps hatch the plan…Earl has to die.

Now, the thing that intrigued me about the song was the storytelling. They manage to build this entire world — give you details about the friendship, walk you through a murder, get you on their side — in a matter of minutes. Not a movie or a six-part series, but a short song. But somehow, there’s considerable depth, a lot of colour to the story and the characters.

Mind-Body-Body Problem (After Junji Ito), 2022

As a painter, I thought that’d be an interesting challenge. Can you, like The Chicks have done in a song, tell a story in a series of paintings? A story you physically walk and move through? And more than just illustrating a story, can you express the same depth? Have it stand on its own — draw you in, intrigue you, where is this going? ‘Oh shit! But, wait, oh yes, let’s go’. In short, can it move you the way the song does? A world-building exercise.

Storytelling is thus pivotal to your work. Whether it’s to convey a specificsense of mystery, like in the 2020-22 series on the night, or an actual concatenation of events, a single painting exists in relation to the other. Thinking in these terms, what was the difference between your old works and this last series?

Surely there’s some stylistic coherence. So they’re loosely related. But I mean, every year of my life you could ask me to look back two years in the past, and I’d be slightly embarrassed of who I was and what I was doing. You could read that really pessimistically, but the way I see it…if you’re not feeling that way, you’re not evolving.

Blue Kitchen, 2021

While talking about your upcoming show, you told me that the theme of the song slowly became close to your personal life while you were painting the series. In what sense do you think that this song by the Chicks and your translation of it in paint can be relevant for yourself and for collective society, women in particular?

Making the works, you’re forced to view the Goodbye Earl narrative through the cultural context of 2022. It’s not just an arbitrary story. It’s about friendship, relying on your fellow women, revolution if you will. That if it really has to come down to me or you, well, I’m choosing me, bitch. Fuck you. That rings different after 2022, after overturning Roe. Gives it a stronger bite.

But still, there’s a femininity to the murder. They kill Earl over dinner. Compare that to, say, the Goodfellas painting (from this series) — the opening scene, Pesci, DeNiro and Liotta are driving down a dark road, they hear some bumps in the trunk. They pull over, open the trunk, where there’s a guy, barely alive and covered in blood. Pesci stabs him a bunch, DeNiro shoots him multiple times, and Liotta’s voice-over: ‘As far as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster’.

You gotta love that these ladies didn’t want to kill someone, didn’t want to take it there — so when they’re forced to, it’s considered, it’s bloodless. Just a poisoning of peas.

How do you see your work developing in the future?

It’s an opportunity to experiment with new colours, new themes. I hope it feels completely different.

Evil Twin in Vivienne Tam, 2022

Artworks

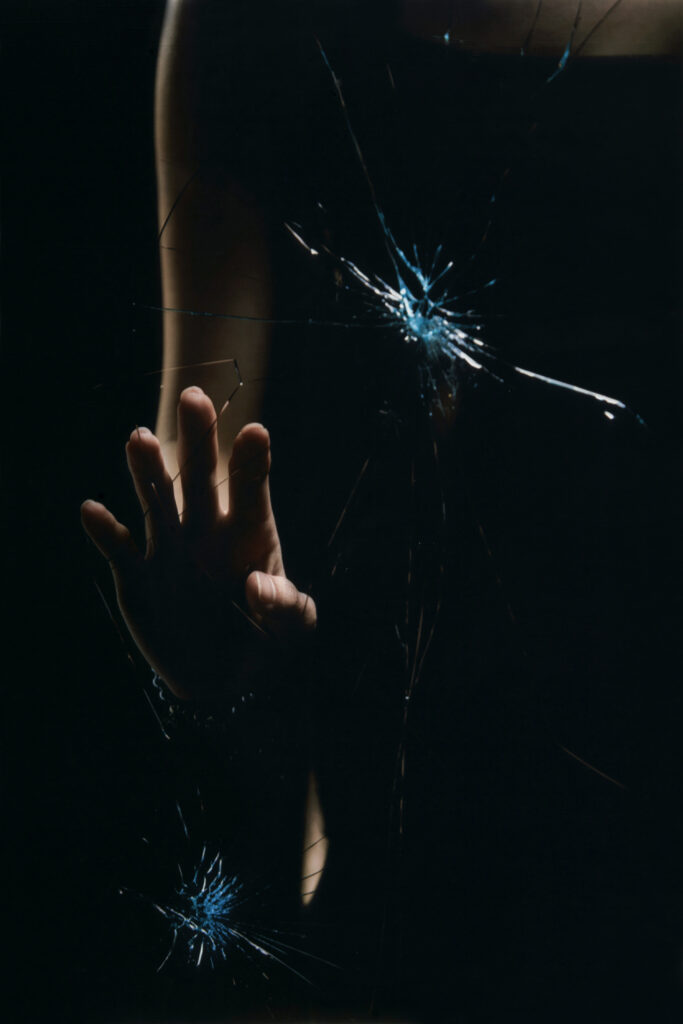

Team

Photography · Tommaso Montenesi Posch

Art Direction · Luca Paolantonio and Tommaso Montenesi Posch

Styling · Luca Paolantonio

Casting · Morfosi Studio

Hair · Dominique Ascione at Blend Management

Makeup · Raffaelle Tomaiuolo at Blend Management

Set Design · Giulia Zollet

Models · Samuele C, Ko Eun Woo and Paul

Photography Assistants · Marcello Raguso and Maria Luisa Zoccoli

Set Design Assistant · Elisa Grumi

Poster Design · Pierfrancesco Gallo

3D Artist · Michele Ciniero

Designers

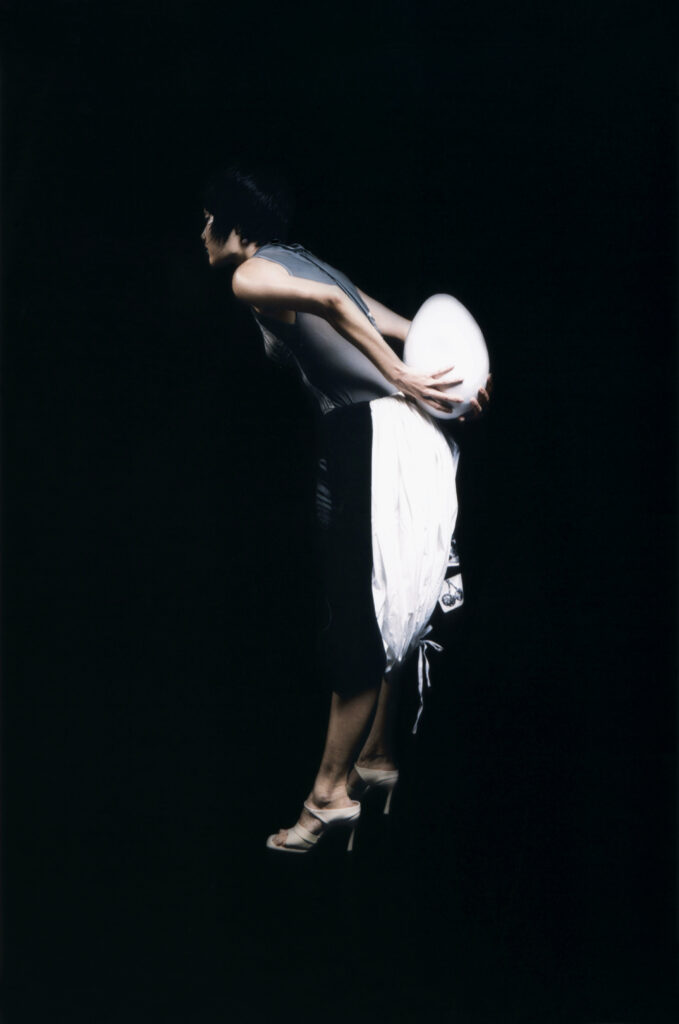

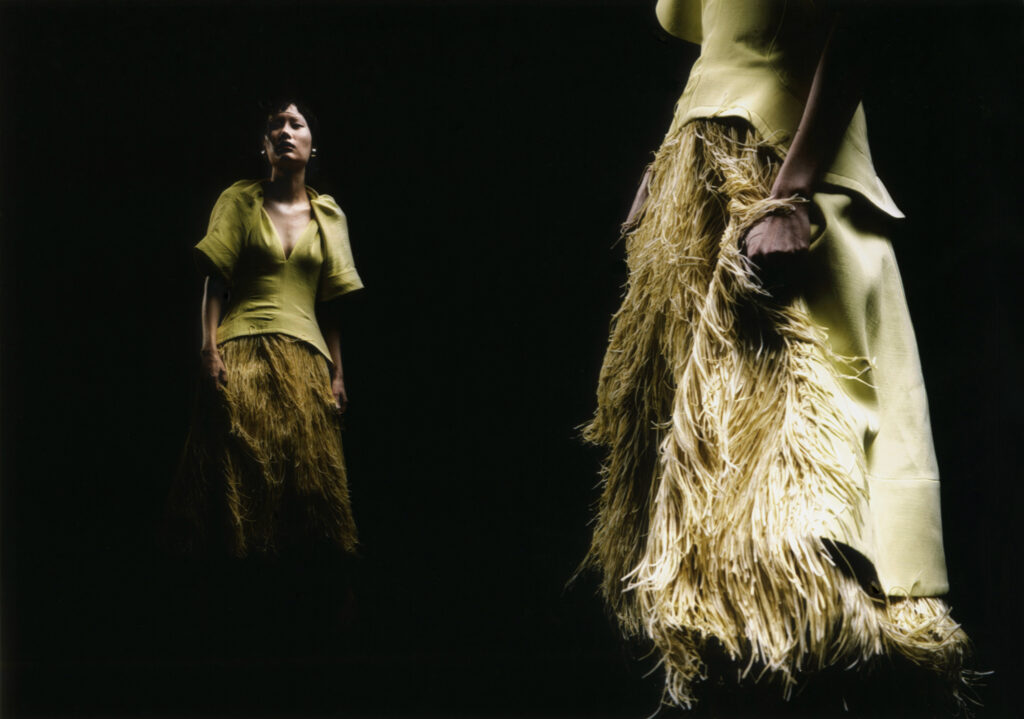

Team

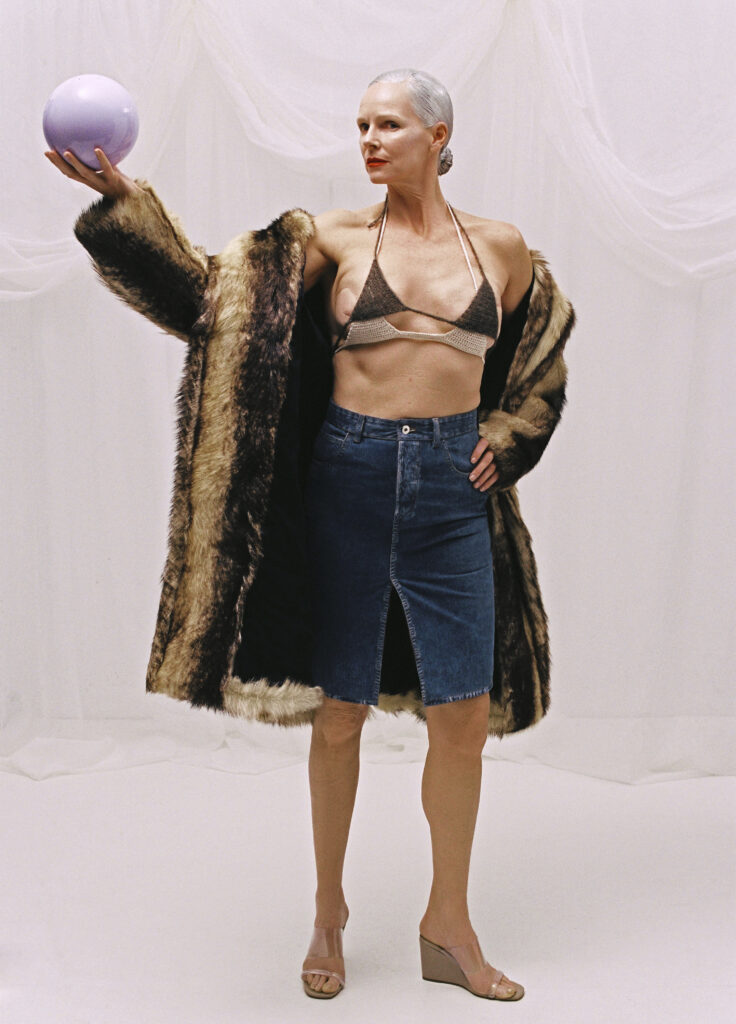

Photography · Andrea Lamedica

Co-Creative Direction and Styling · Allegra Coccolo and Sonia Alipio

Casting · Sofia Michaud

Hair · Davide Perfetti

Makeup · Filippo Ferrari

Model · Jiyeon Park at The Lab Models

Photography Assistant · Francesco Imbriani

Styling Assistants · Seo Young Kim, Anna Di Bernardo, Francesca Filosa and Enrico Calvo

Production · Clara Giberti, Coming Studio

Designers

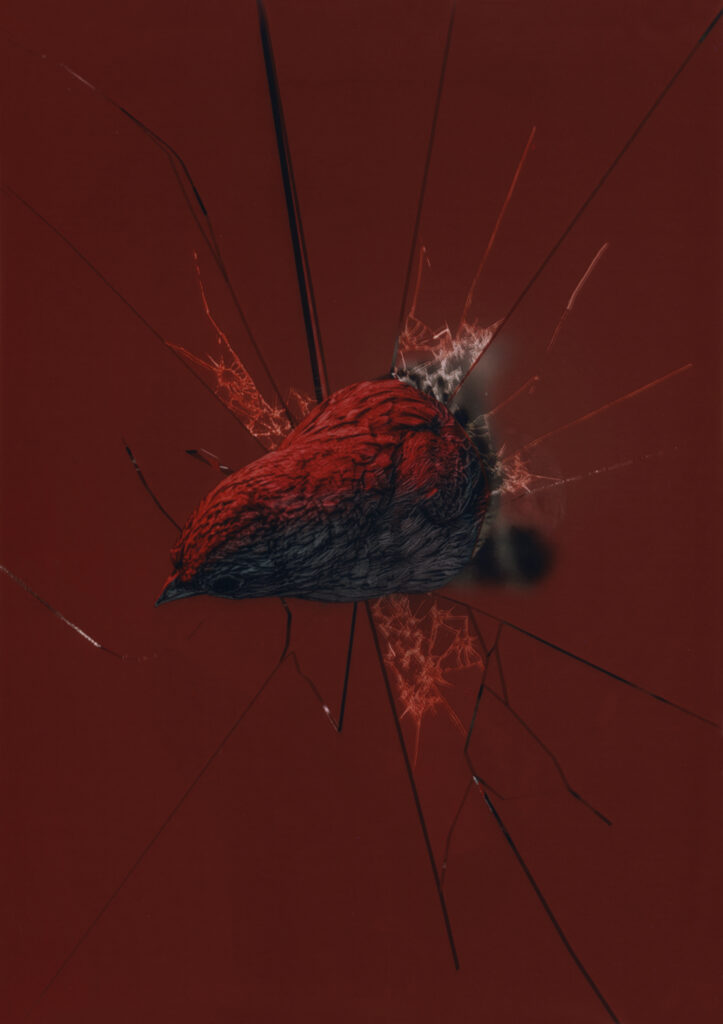

Team

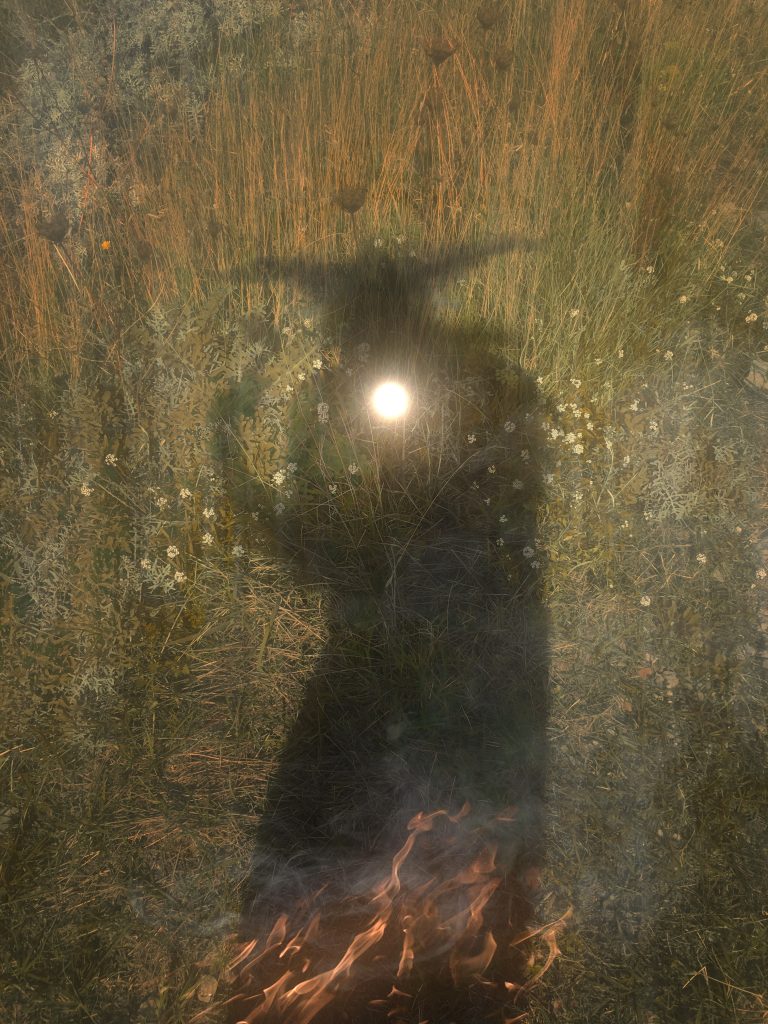

Photography · Celine Paradis

Art Direction · Celine Paradis and Indra Zabala

Styling · Gina Berenguer

Casting · Alexis Ocón at Gaze

Hair · Manuela Pane at Kasteel Artist Management

Makeup · Mariona Botella at Kasteel Artist Management

Set Design · Indra Zabala

Models · Irene Sesé, Sasha and Delfina at Uno Models and Claire at Francina Models

Light · Pascal Schrattenecker

Retouching · Alba Nieto

Location · Committee Studio Barcelona

Designers

The Trip, 2022

Sun Woo (b. 1994, Seoul, South Korea) is a visual artist whose work embodies the intersection between two cultures and generations, and the way technology can inform and transform artistic practices. Born and raised in Seoul, South Korea, Sun Woo migrated to Canada around the age of ten and despite the challenges of being an immigrant, the experience of growing up between two cultures has deeply informed her identity and artistic practice, especially in a time of rapidly shifting technological landscapes.

Her compositions evoke traditional paintings with a precision almost only possible digitally. By integrating digital tools into her practice and merging them with analog approaches reflecting the generation and cultures in which she grew up, Sun Woo explores the intersection of technology and the human experience. Her work reflects the sense of in-betweenness that characterises the contemporary experience and questions the location of the body in today’s technology-filtered reality.

Sun Woo discusses with NR her upbringing, her creative process and the messages behind her recent exhibitions. She explores how her experience growing up between two cultures has influenced her work, why she chooses to use a combination of traditional and digital techniques, what she hopes to convey through her art and her perspective on the merging of cultures and technology in contemporary art.

Fountain of Secrets, 2022

You were born and raised in Seoul, South Korea but left for Canada around the age of ten. What are your earliest childhood memories there after migrating? How did those two places aliment your desire to create and paint?

When did you start creating? When did you realise this was something you wanted to pursue?

Moving to Canada was not an easy experience as I had to leave my life at home behind and adjust to a completely new environment. Even in the company of friends, I constantly felt alone and never fully understood, which naturally led me to seek other things that could help fill these holes. These first became movies and magazines rented from my aunt who ran a small variety store in town, and later on, new devices such as computers and online platforms began to emerge. They allowed me to remain connected to my community in Seoul, but the physical distance still made me feel like I didn’t belong anywhere.

“I think this kind of upbringing and the sense of groundlessness strengthened my desire to create and paint, as it gave me a voice that was free linguistic and cultural barriers.”

When I moved to New York to attend college, I began to pursue my practice more seriously. Placing myself in a community of artists triggered me to dive into art making as something I’d like to continue to pursue. So after receiving my degree, I moved back and got a studio in Seoul, which is where I’ve been based since then.

What would you say has been most impactful from the merge of these two cultures? Is there one you feel more strongly attached to?

Your compositions evoke traditional paintings but with a precision almost only possible digitally. Airbrushing, hand painting, photoshop are some of the traditional techniques and digital tools you use for your artworks. Why have you chosen those? How do you think technology and analogue coexist together?

I think both my identity and practice have been heavily informed by the experience of growing up in between two cultures and generations. Being an immigrant in a time of rapidly shifting technological landscape allowed me to reach my homeland any time through the screen, while staying physically tied to the cultures of a foreign country. At first, it was difficult since I was born before these devices were introduced and had to teach myself how to utilise them. But they gradually became an intimate part of me, both as a friend and a channel into the world beyond physical bounds. This experience naturally led me to integrate digital tools into my practice, merging them with analog approaches as a way of talking about the generation and cultures in which I grew up. Through this process, I also wanted to reflect on the time that we’re living in, the sense of in-betweenness that comprises a large part of the contemporary experience.

“I often find that my identity bears resemblance to today’s digital images — the way they wander without an anchor.”

Circuit of Requiem, 2022

On one hand, I think this sense of empathy drives my urge to take these images out of the screen and ground them in the physical space of a painting. Because I imagine them as virtual bodies floating in the online environment, the process of distorting and augmenting them on Photoshop reflects my interest in exploring the transformative aspect of contemporary body, fostered by its increasing interaction with technology. By bringing them out of the web, giving them a tangible form through bodily labor, and putting them back on the Internet, I’m trying to question the location of today’s body — including my own — especially after much of our activities have transitioned into the digital sphere after the pandemic.

Could you tell us about your show ‘Memory of Rib’ curated by Jeppe Ugelvig with a special screening of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Mouth to Mouth (1975) and your show ‘Invisible sensations’ at Carl Kostyal in Milan in May 2022? What were the messages behind these exhibitions?

‘Memory of Rib’ was a show that brought together a group of artists whose works evoke or deal with the idea of corporeality. It explored concepts like the body’s instability, limitations and contingency by looking at the ways in which it interacts with today’s technology and sociopolitical landscape, while also thinking about how we detect and identify with images of the flesh seen in commodities and media. It included a diverse range of artists in terms of age, sexual identity and cultural background, especially with Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, whose work from 1975 provided a historical anchor to which younger generations of artists could contribute their discourse.

The works that I presented in the show, titled Silent Companions and Baggage, developed from my research on prosthetics and medieval armours and weapons — tools that have evolved to complement physical weaknesses and came to function as literal arms, legs, and skins of an individual.

“Weaving these histories with the relationship between today’s body and technology, I tried to construct compositions in which the organic intersects or collides with the mechanic to become something transcendental.”

Through images like melting meat-candles and strapped rock-flesh, I tried to address how it feels to be a body in a digitally mediated world, which at once “enhances” you and nurtures your feeling of insufficiency.

‘Invisible Sensations’ was my solo show that opened earlier that year, and it also dealt with the emotions and sensations related to inhabiting a technology-filtered reality. It included paintings and 3D-printed sculptures that evoke body’s limits, vulnerabilities, and struggles to resist their mortal fate, as well as social constraints that continue to oppress the female and coloured body. Images of my own body parts, including medical scans that I carried with me at the time to treat a prolonged illness, were collaged with elements that allude to mechanical presence, becoming fragmented, reconstructed, and translated into otherworldly beings. Through this convergence, I tried to look into the fragility and endurance of today’s bodies and question the extent to which their unification with technology can liberate them or transform the atmosphere they inhabit.

Diligent Heart, 2022

How is the process usually for you when putting together a solo show?

In my past interviews, I’ve revealed that I collage images via Photoshop. But even though my works are presented as images, they actually begin with text. From stories to dissertations, various sources of written materials provide inspiration for my work. Despite this, I am interested in creating something that can only be communicated by being in the presence of my works — something that is to be experienced and surpasses the written language.

“Paintings are not simply re-enactments or something that fits perfectly into an existing theoretical frame, but they are a result of materials that I channel through my own body and create to evoke a response that cannot be fully harnessed by rationality.”

Sometimes, the exhibition space also determines what I decide to paint, even when it’s a white cube. It is important to me that the works speak to the space and vice versa, and that the work is presented in a way that reinforces the viewing experience. As a result, I tend to spend a lot of time contemplating on such a dynamic, which often determines the work’s size and form.

Detail crops from The Crimson Letter (Triptych), 2022

Your work also interrogates Korean societal desires and more specifically the ways in which female bodies are viewed and represented. Could you talk more about that? How do you think gender roles and stereotypes surrounding being a woman in Korea, will evolve?

Because my practice interrogates today’s social condition and technological landscape through the lens of my own psychological and bodily experience, many of my works are inevitably tied to my identity as a Korean woman. In result, they often speak to the experience of being a female body in both online and offline environment, as well as a body inhabiting two different cultures.

In addition to my painting practice, I’ve also been working on a project called Dadboyclub with an artist and friend, Sangmin Lee since 2021. Dadboyclub, to both of us, is a platform to channel issues specifically regarding the experience of being a woman. For the first iteration of our project, we exhibited virtual ‘products’ that each house a story about womanhood. Objects like an inflating, studded baby pacifier that obstructs a woman’s throat, or a ‘flower’ with a rolling eye that detects and destroys hidden-cameras with automated spears, reveal the conditions and violence women may experience in society through a long-winded joke. These products do not actually exist, in real life nor as NFTs — so they cannot be sold — which was an important aspect of this ‘virtual store,’ which was also a commentary on how female narratives embodying pain are consumed as entertainment online or through popular media.

Sinkage, 2022

Absurdity is a driving force of this practice, as we navigate the ways we can express our discontent with inequality as well as emotional pain that is regarded as superfluous. Whether it be a small feeling from a failed relationship, to discovering violence embedded in the myth of Psyche and Eros — Dadboyclub re-situates women’s stories, old and new, revealing a prickling truth of reality that was often disregarded as minute and obsolete. We believe the personal is political.

There have been some progressive developments over the past few years regarding gender issues in Korean society. There has been a change of perspective regarding parenting and housekeeping especially, which have been regarded as female duties up until very recently. More women are speaking up about sexual violence and trauma, which have been looked down upon before the Me Too Movement in Korea. But at the same time, there still remains a local issue of victim-shaming and the taboo of publicly claiming yourself a feminist, grounded in the society’s age-old history of Confucian patriarchy.

“Discussions regarding female equality are voiced more often, but with the growing polarisation between a progressive agenda and right-wing counter-movements — which seems to be a global phenomenon — the backlash hits harder, making it difficult to gauge whether we are moving forward or simply repeating the past.”

Which other mediums and tools would you like to explore? Would you consider using AI systems such as DALL·E?

Actually, my current practice already involves AI in a way, since I often use images that are fed to me by my search engine and social media — which, after analysing and machine-learning my interests, provide me with new sources. In this sense, I often allow my devices to become the agent rather than controlling all aspect of the process, and the resulting work becomes a joint product of these voluntary and involuntary selections. Even so, I sometimes find new programs like DALL-E quite haunting. How do artists justify their practice when AIs actually produce artworks on behalf of them? What new roles are we to take on?

Detail crop from Diligent Heart, 2022

There is a certain longing for the 2000s in your work. Is there any recent pop culture events that has marked you? What are some of your favourite music albums and films?

I think my works embody a sense of longing and empathy in general, not only for the 2000s but also an older past or even the future. They sometimes long for a certain time, place, or person that I’ve physically experienced but also ones that I haven’t. I find this faux-nostalgia, a longing for a time that I do not know, to be an interesting cultural phenomenon that I also engage in. In this sense, the convergence of the physical and virtual plays not only into the process and medium with which I work, but is also echoed throughout the narratives and depictions that drive the work.

No-landing Flight, 2022

How do you feel our hyper consumption of media is shaping us? Do you think we risk to lose ourselves if less time is spent on building connections or do you think it is an inherent part of shaping our identity?

In this new age of technology, how do you ground yourself?

I also find it hard to navigate a time like this, where you’re seeing so much and being surrounded by so many people, especially through social media. From a certain angle, I feel like the world seemed much smaller when we were less connected, as it gave each of us more presence and weight. Now it seems to be the other way around. Our sense of importance seems to dwindle as we become exposed to the lives of so many strangers and ours constantly displayed alongside theirs. We’re endowed with more options of things to see and people to meet than ever, but simultaneously, we also become one of those options as well. These are some of the things that I’ve been thinking about lately, and how do I ground myself in an age like this? I still don’t have an answer to that.

Dadboyclub, Camouflower, 2022. Website

What was the first piece of art you saw that left an impression on you?

Francis Bacon and Louise Bourgeois were among the very first, and they still continue to inspire my practice.

Credits

Artworks · Courtesy of the artist and Carl Kostyál Milan, London, Stockholm.

Female Pentimento summons liminal portals to apocalyptic ecstasy, fairytale daydreams and irreversible escapism. They blast saturated white beams more powerful than a spotlight; more sacred than a burst of sunlight at the end of the rain. They draw from human experiences, seemingly projecting the artist’s personal encounters at times, and lend support to viewers by digitally opening new doors for their worries and fantasies. Female Pentimento’s nurturing principles have harvested a tight-knit community whose eyes for art are satiated, ears for wise words quenched, and minds for optimism fed.

The New York-based visual artist positions herself as virtual holy water solidified by her purpose in this lifetime to impart beauty and hope through words, images and music. She finds her self-design in bringing positivity into the double-tap realm to be a constant spring of inspiration for her followers to lap up. Her unearthly visuals reap the seduction for optimism. Her floating palm-sized butterflies pocket luck that guides people out of their limbo thoughts and toward a deep sense of calm. Her multi-winged phoenix brings the prophecy that whoever holds their gazes at its orb of light shall be gifted with prosperity, in a way that it has never entered their lives before.

Every image she creates even comes with a short caption that offers itself as a mantra for manifestation. I protect my inner landscape from all harm, forever. I no longer scare myself with my own thoughts. The most miraculous things happen to me, and I am in awe of all the incredible experiences that enter my life.And when the sinews of my thoughts tear, the miracle I need comes gently into view.

For NR, she lets our readers in on her light-filled purpose and life that ranges from art to music.

What were your earliest memories of art?

I think on some level I’ve always wanted to do something with the arts. As a child, I was mesmerised by the piano, and later down the line, painting. I didn’t truthfully grow up with a ton of art influence around me though, outside some of the obvious avenues, like cartoons and anime.

My earliest memory of encountering fine art is when I was in 6th grade and my mom brought home prints of Ansel Adam’s work. I didn’t think much of it at the time, but that was likely the gateway to me dialoguing with artwork in a more critical and meaningful way.

How did you come up with the moniker ‘Female Pentimento’?

For me, the power of having a stage name is that it gives me permission to explore a new heart dimension without being constrained to what I already think I know about myself. My ultimate intention is for the name to touch on this idea of revealing hidden aspects of oneself, just as a pentimento in art refers to the reappearance of earlier layers of paint.

In this context, the female’ aspect of the name emphasises the idea of a feminine presence, revealing parts of the self that were previously hidden. I hope to others ‘female pentimento’ suggests a sense of uncovering and reemergence with a focus on the experiences and perspectives of a feminine energy.

As for the history behind it, I was brainstorming ideas of what I wanted my moniker to be and I kept returning to Picasso’s ‘The Old Guitarist’. In the work we know today, we see the iconic, downtrodden figure of a man in anguish — however, underneath the image is an original underpainting of an unnamed woman breastfeeding a child in a much more lush, idyllic scene.

“I always thought that relationship made for an interesting metaphor around my own gender identity and mental environment.”

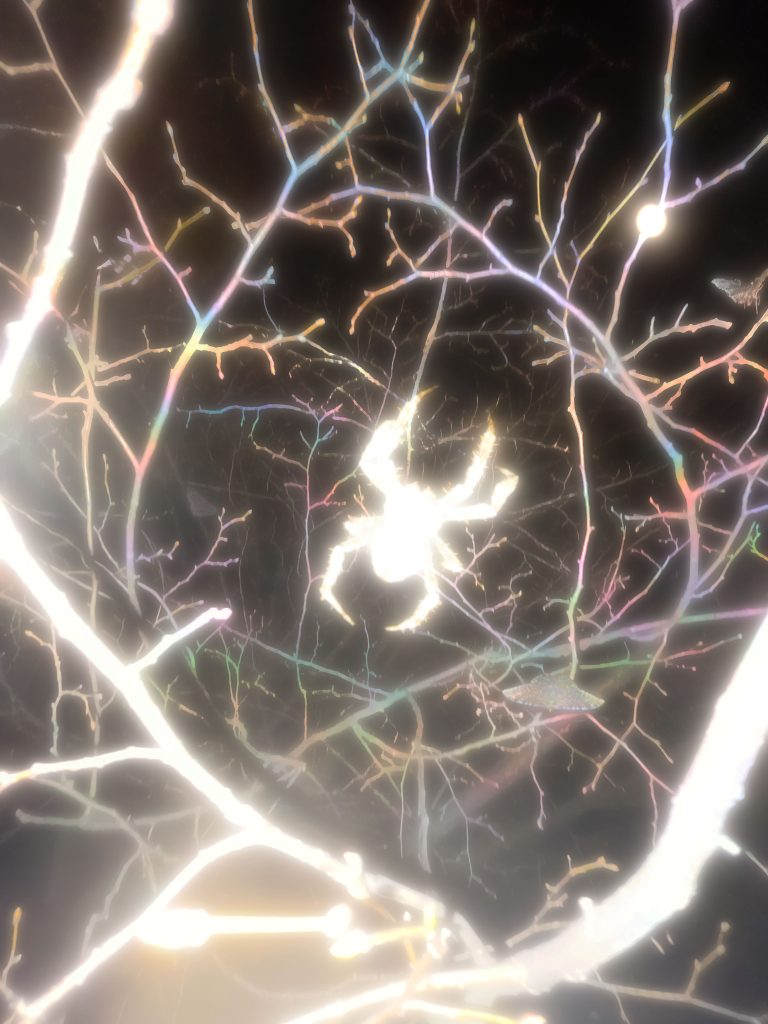

Tell me about your journey to light becoming your source of visual inspiration.

Over time, light has just become an instinctive element I’ve been drawn to. Since I started focusing on photography, I’ve been interested in all sorts of different natural phenomena including sunlight, lightning and rainbows.

I love how symbolically loaded these elements are throughout cultures and art history. I find light (and nature) a universally understood language that doesn’t have all the conceptual red tape that other subject matters have. One could look at a photograph of a wildfire stretched across a landscape, teeming with wildlife, and know instinctively how to feel about it.

Many, many creatives have influenced my present work, and the lots of visionary artists that come immediately to mind are Agnes Pelton, Hilma af Klint, Belkis Ayon — the list goes on and on.

How was your environment growing up?

Growing up, my environment was a bit chaotic. I was raised in a single-parent household in a small southern town in Virginia. We moved around a decent amount as my mother was a minister, and the church relocated us regionally every couple of years.

I imagine anywhere I grew up would have been a challenge for me. When I was young, I was a very sensitive and shy child. I used to see those attributes as more of a liability, but as I get older I revere the tender and reserved parts of me the most.

Do you see your works as touching upon religion, faith, or both?

I think the first part of the question is for the viewer to decide. What I can tell you though is that when I’m creating, I borrow a great deal of inspiration from different religions and spiritual practices like, but not limited to, interconnectedness, spreading kindness and advocating for mindfulness.

As for my personal practice, I’ve been describing myself recently as a biospiritualist, which is an ideology that posits that the biological is inherently intertwined with the metaphysical.

How does nature empower you as an artist?

It’s the catalyst, the subject, and the artist in my mind. I don’t think I’ve created any recent work that doesn’t bow deeply to the natural world.

“I see our earth as the ultimate wellspring of inspiration.”

What’s your inspiration for making portals that seem to be passages to unearthly worlds?

Portals are probably one of the most magical elements I experiment with in my images. Sometimes, they border on the fantastical (or unbelievable) end of the spectrum, but I think living in a para-reality is often the job of an artist. That is, thinking beyond what you know to exist and imagining a world of what could be. I like the idea of living in that space of potentiality full-time; it keeps me curious.

Do these portals symbolise a form of escape from reality?

Certainly. In some instances, portals convey the idea of transitioning from one realm to another, offering a way out of the physical world. In others, I find it fascinating to reimagine myself as the light source or portal, and to consider what it would be like to exist in a non-corporeal form.

How do you come up with the often inspirational and reflective captions behind your visual works?

The captions I attach to my images often stem from phrases and ideas that I feel compelled to remind myself of. They are often direct affirmations that I use to uplift and empower myself. Through these words, I hope to offer others a similar source of comfort, hope, and inspiration.

I’d also add that I’ve been deeply influenced by authors such as Jack Kornfield, Louise Hay, and Marianne Williamson to name a few, who have shaped my understanding of the power of affirmations and positive thinking. They have inspired me to craft mantras that not only accompany my visuals but also uplift and empower those who encounter them.

Do you see yourself as a guardian of light, both visually and linguistically?

Over the last few years, I’ve felt strongly that my calling in this lifetime is to impart beauty and hope to the world.

I trust in my ability to live up to that goal. I know I can do it.

“Whether through words, images, or music, I think my greatest purpose may be to bring positivity into the lives of others and be a source of ongoing inspiration.”

Credits

Artworks · Courtesy of female pentimento

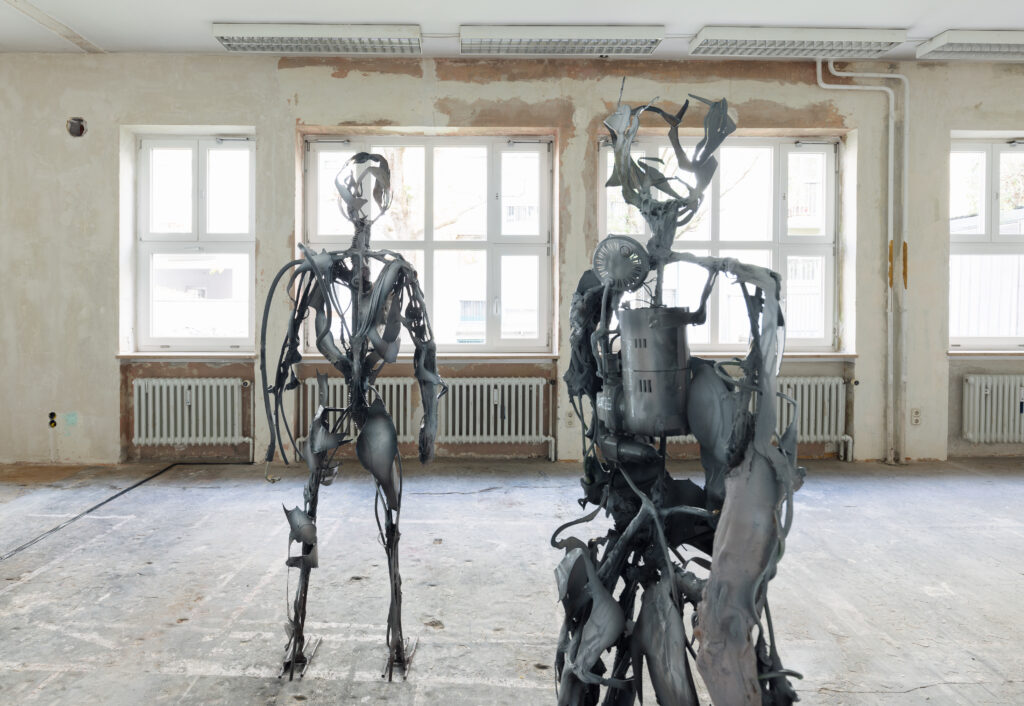

After completing her Bachelor of Fine Arts in Seoul, South Korean-born artist Yein Lee went to the Academy of Fine Art in Vienna, Austria. She stayed there to live, refining her technical prowess into an intensely profound body of work. And she is far from done.

Combining her past experience, dexterous innovations and interest in advancing technology, Lee has exhibited her work in numerous locations, showing her work ten times just in the last year. Her sculptures have approached the world with the strength of a cyborg. Their creator has constantly developed alongside them, her mind evolving with the same creative mental software that transforms these objects into personable, breathing beings.

Her work has an unrelenting originality. The sculptures are crafted into augmented forces. Lee approaches the overall composition with creativity in mind; she creates the presented proportions, and her treatment of the fabricated flesh can be felt through panels and poles. Lee installs biomechanical forms that brush against the fabric of a wall. The dark, drooping and dagger-sharp bodies poke out of the white walls of a gallery. Xylophoned rib cages jerk out with splayed bones, like arachnid arms reaching around a polymer and epoxy heart. Loose limbs fall like sinuous vines bleeding black and stretching into nothingness like the electrical wires that they are. These forms are obscure and anything but human. However, they hint at a humanity that can be found within ourselves, only with multiple jabbering mouths sealed in polymer paralysis. If humans are contorted in hate and loosened by drink, Lee’s hand-made creatures are intensified with the cold glitter of a PVC plexiglass and wires that twist like wilted willows.

These are not merely artworks in stasis. They transform over time and have a life of their own. Lee transfers the essence of being into objects with an actuality and reality at their core, giving the pulsations of a creature with a soul.

You originally studied traditional painting in Seoul and then moved to Vienna. Since finishing up at The Academy of Fine Art, you have continued to live there. It has been almost a decade since you graduated from University in Seoul. Why did you stay?

I had no idea about the city at all. Soon, I decided there was a young, active scene going on, and there were many spaces for artists to produce, especially considering the smaller scale of the city. Many artists were around the city, and everyone was working around me, and I enjoyed this input and movement. Now I really have a sense of community here.

Did this sense of belonging come immediately or over time?

My friends are here, my partner is here and my studio is here. I now know how to source my materials, and I know how it works here when it comes to running my studio. This usually takes some time. You have to get used to a German-speaking country and then deal with the art bubble (which is all in English).

Your material practice has branched out from the norm and has spread into the realms of technological components, metals and alloys, and plastics and organic materials. At what point did you move towards sculpture?

Through my BA in Seoul, I focused on Asian painting, and then for my Masters, I followed a more modern path with Contemporary Art Direction. I went to Berlin and then went to Vienna for the Academy of Fine Arts, where I continued in the painting class. I struggled a bit as I couldn’t find my own visual language through paint. At the time, the whole Zombie Figuration discourse was going on (in the mid-2010s), and there was an overwhelming overload of paintings.

So, what did you do?

I tried to forget everything I had built so far, and I decided to leave Vienna and go to Shanghai for an Artist Residency Program. But I didn’t bring any material with me, on purpose. In the program, there was a lot of leftover material from the previous residents, so I just collected it all and began using these random materials that artists had left behind. Leaving my old studio behind and starting with new tools was really helpful. I started using hot-glue guns, plastics, acrylic colours and polyurethane. I started working with these new materials, and after that, my painting became more sculptural. When I returned to Vienna, I kept experimenting with different materials and processes, and learning casting and welding helped me get closer to what I was looking for.

The scale of your artwork varies, yet the forms depicted remain relatable. One can see a drill-motor heart and limbs of steel, a chest with spread combs like fork prongs and body positions that feel so human. When you returned to Vienna, how did you start collecting the materials for your sculptures? Are there human elements you search for which operate as surrogate body parts for the forms?

I like that it feels human. In 2018, I really started getting into sculpture. I turned to casting and melding metals out of curiosity, but soon I fell in love with it. After using these plastics and metals for painting, I began making the frames for the works, which later became structures in themselves. As I explored these forms of matter, I knew I needed an anchor to communicate with the viewer, as my visual language of monstrosity tends to be less communicative and more framed. Using the human form was a translator. There has always been a presence of organic matter in my work. Even before I went to Shanghai, I had always used bodily elements; when I returned, I deepened my research on organic structures and was influenced by pop culture and movies. This all helped push out my creativity, and body machine parts started working as surrogates, but sometimes they just expanded on body parts.

Technical skill is a quality by which sculpture is evaluated. Does your practice involve meticulous working and reworking until you are happy with the result?

Every time I work, there are millions of possible next steps to creating the sculpture. For example, how much should I bend this piece of metal? But I like that. It is nice to explore these possibilities and refine the options for finality.

“Finding what’s ‘right’ is a thrilling feeling.”

And how do you know when to stop?

I could pretend to be a genius and say, ‘I just know’, but there are rules to follow for basic forms; I have an individual formula, focusing on the completeness, content, consistency of form and ratio of texture to balance in the composition. When everything fits into what I want to talk about, I know it’s done. I’ve definitely grasped more of an understanding of finality, which came over time and through more experience with my materials. The experience gives me more choices in what I can do. The experience makes it easier to see what is possible.

“The point of arrival for artwork is the ability for the piece to be presented.”

However, for many artists with a strong technical focus, the mastery of a process can be overlooked for a purely aesthetic interpretation; it can become cold. Despite this, your pieces have a lucidity, a sense of being which can speak.

How do your technical skills allow you to grow such a concept?

Coming from a painting background, I came into sculpture with quite a messy and dirty technique, but I let it be like that, and it turned out that I liked doing it the ‘wrong way’. For instance, with latex, I was supposed to pour it carefully into the mould, but actually, I did it the wrong way to try something new. It gave me a more instant expression. At times, being used to traditional techniques makes the work enter a certain frame, whereas what I wanted to say about sculpture and how I wanted to expand my work was more fluid; let it drop and overflow. I thought, ok, let’s break some rules, see how far they can be broken and how I can use the pieces, whether they are ‘failures’ or not.

Do you wish for your sculptures to communicate with the audience somehow? Do you want them to breathe like us or remain objects for opinion?

I always have my own intentions and ideas about my sculptures. Sometimes I have favourite parts of a work and what it is supposed to be. However, once the sculpture is out of my studio and leaves my hands, it is not mine anymore. Sculpture should have its own agency, and it should be able to deliver certain things to different people but without the arrogance of a god. I like to leave it up to viewers with what they see. Sometimes it is very different, and I think, ‘that’s ok’.

How does it feel to separate yourself from them? And how do you feel about your work as a whole?

I feel strange. I do a lot of drawings, but they are not necessarily related to the outcome. Some parts of a drawing can be involved in this outcome, but the journey is only partially planned. Once I have finished a piece, I think, ‘what are you?’. Sometimes I feel alienated from the sculpture, and other times I feel attached to it. It’s a weird mixed feeling because I never planned to make this sort of work. After completing a sculpture and it is sitting in front of me, whether it is the scale or material elements, It still takes me by surprise.

They also possess a depth that seems personal. Rather than being shells or a disregarded snakeskin, they could almost be seen as extensions of your personality. Is your working method related to this emotional connection?

I make my sculpture in a way that fits my personality. My working method is who I am. I am always slightly rushing, determined and sometimes slightly clumsy and rough. But my character is shown throughout my work, and it’s funny to see it, but the gestures do show.

Are they autobiographical?

They express how I feel, but they aren’t autobiographical. Many artists take inspiration from their experiences, so some of my experiences are embedded into the process and final outcome. But then, for me, it often gets separated; the initial idea that exists when I start a work sometimes changes while I’m working as my thought process goes into a meshed structure rather than a linear method.

When you are in the process of making these artworks, what do you feel and see? What sort of environment do you put yourself in (besides the physical surroundings of a studio)?

Not too often, but sometimes I get into a trance. It feels like a buzzy, feverish and floating sensation when I really concentrate, but that could also be the caffeine and exhaustion. When I get highly focused and concentrate so much, I get absorbed into the process so much that my body disappears and it is just my brain and hands.

How do you want people to react to these works? The sculptures are hardly embodiments of peace and harmony. At least in the conventional, Edenic sense. Sci-fi characteristics emerge when words like ‘hybridism’ and ‘cyborg’ are thrown around. Still, your work takes a step further by removing the past and melding present silhouettes into alien forms articulated to a raw framework you have created. How do you react to sci-fi labelling and labelling in general?

Hybridity has been such a significant term that has circulated, but it is now a natural concept at this point. With sci-fi, the concept is a current metaphor for our imagination and society. It is a present-term idea that moves around our dreams and narratives. There are many bodies today that are very attached to artificial material, and I see the hybrid concept as a phenomenon that already exists. I was always more into manga and animation, so I got more ideas from these magazines than from traditional sci-fi; I didn’t grow up with it, but lately, I’ve been watching all the classics, but only as an adult. My works are about what I see and observe, but people can receive them as one ‘type’ of art. It is the same with science fiction: it gets categorized as one thing. The artist Ivan Pérard says, ‘Sci-fi’ is a modern fable’, which I very much agree with. Animism and mythology operate around nature and culture, and science fiction mirrors society just as much. It is about our life as it stands now.

And what do you want to change this attitude?

It is essential to keep talking about art in a way that doesn’t limit terminology and simplifies the language that describes it. In my work, there are lots of languages of monstrosity, and people immediately think of the artist, H.R. Giger and how many monster-esque forms are coming back in art.

“The sculptures embrace distinct ambivalent emotions.”

For me, the works are in a status of becoming. I want people to discover hope in the form of reflection on our current society. It is necessary to focus on the details and have more sub-categories to be aware of.

Do you think your work promotes that concept?

I hope so. I have been trying to find a way to communicate it with metamorphic presences, blending the ‘me’ and ‘you’ and ‘us’. For that reason, I worked more into the human form to express a language of monstrosity that is less misunderstood and more anchored. Making these forms relatable makes them beings you can communicate with. Components resembling human body parts communicated and specified what I wanted to say.

These sculptures have their own weight. They possess a dense mass that stands perfectly. They support themselves just like Francis Bacon’s creatures in his Crucifixion paintings did. There are various rods and stabilising factors involved. However, these prodding protrusions make the artwork whole by grounding the body and creating a proportionate form. How do you want your work to stand?

Through wires and steel supporting the sculpture’s weight, they can look weightless and rooted to the ground at the same time. Being in the air is a nonhuman thing, and my works take components of human anatomy beyond bodily function. I want them to stand with natural and artificial elements growing from this body coexisting.

And towards what environment do you see them moving?

I want to explore all sorts of locations. I don’t just want my work in white cubes. I’m working on this sculpture park exhibition in the Netherlands which will be interesting; the surroundings there are radically different, which will also dramatically affect how the sculpture behaves and how it is interpreted.

Your production has led to your works avoiding the limbo between weightless futility and a heavy, immobile mound. In many senses, the fact that these works float yet are still weighed down by gravity makes them appear as embryonic creatures captured in stasis. Do your choices in materials and proportion impact the presentation/display of your works and their ultimate impact on audiences?

Proportion is only one part of the decision-making on form, so it’s hard to say it’s the ultimate effect, but it is crucial that my works have a certain openness. With Devouring Chaos (2022), I liked having a balance between the human anatomy, electrical wires and wooden branches that poke out of the skins. The branches make the piece float in the air and, at the same time, stay rooted to the floor as if it were a plant. I like having a duality and coexistence of weight and weightlessness, a growing and wilting being. I find that concept really interesting, and I want to explore it further in a different direction.

A word that sparks to mind when observing your work is protuberance. Not only in the content of your subject matter, (as it juts out of a human shadow with the suddenness of a razor-sharp guillotine) but the context of these protrusions. Do you want your artwork to jut out from the norm?

“I want them not just to jut out of the norm but to stretch out the norm and expand normativity. These forms convey that we are all simultaneously different and alike; it is the form that decides the content just as much as the content decides the form.”

How do you decide what form these sculptures will ultimately take?

In the beginning, the size of the works themselves is planned. Because of shipping, the scale is regulated for practicality. When I started working on my latest pieces, I fixed their average size first. However, the forms then develop and grow out of my imagination, and with Devouring Chaos, I got the idea of this fazing face and legs frozen in motion from a long exposure picture. Showing constant movement across frames in a particular image was an interesting visual element that led to a transition in the movement process.

Your expertise in gleaning used and disregarded materials comments on the extremes of consumerism and assists in communicating the issues regarding the state of the environment today. How do you see your art playing a part in the way we move forward?

I would like to embody specific thoughts and concepts in my sculpture. They are metaphors and suggestions. Let’s say a viewer could see a broken iPhone cable as part of my work and wonder, ‘Yeah, I do have a couple of broken smartphone cables somewhere at my home, too’ Then it’s a good start.

And the ultimate goal for them?

Being born abroad and living in a foreign country is frustrating, and you sometimes feel like you do not belong. Even the concept of nationality is weird for me here, and within Vienna, I live in a bubble where I only speak English. It is weird but interesting. I want to explore the possibilities of representing the body in this way. For example, the issues of hyper-consumerism and the ecological crisis come up in my sculpture with aesthetics and materials providing belonging in an extended body. I want to embrace more possibilities of the body. I am not just ‘me’, but I am a human. I consist of thousands of cells, fluids, and microorganisms living with me. This comes out in the work with not only the mechanical components and broken machines, but also branches and formed figures that look like microorganisms and then faces. I try to use macroscopic with microscopic imagery to comment on both the body as an individual entity and the world as a whole.

There’s no missing one of your works. Not only do they jump out with their presence, but they are wholly yours and could be produced by no other artist but you. The structures you make are transformed into a veritable presence that catches the eye in a second. Is there more to be done?

I want to keep creating and working on my career. The practice I want to promote is one where humans are not in the centre of the world, but I want my sculpture to coexist with the world in a way that expands certain areas of thought but not in a ‘core’ social sense. I am happy with what I have been able to make, and I try to give credit to myself instead of just being a perfectionist and asking myself every time, what more should I have done? But sometimes, you just can’t push it further because of budget, time or energy.

Are you confident in the artwork you produce?

There is always room for improvement, but the best thing is to be able to learn from your work and improve upon it the next time. Looking back, I did my best work within a limited time, and although it is difficult, I always want to improve. However, I am happy with what I have done and what I will continue to do. Sometimes you have to move on and keep working on the next piece.

“My confidence is in my desire to explore more possibilities.”

Credits