“It inspires me to see so many young people standing up and having a voice”

What it is to be ‘American’ is, particularly within the context of current affairs, inherently political. Linguistically, ‘American’ is the demonym of ‘America’ – referring to the noun used to denote the natives or inhabitants of a place. But it is also a term that has found itself being actively, and sometimes violently, reclaimed in the interests of a particular form of nationalistic ideology, one that seeks to control who can and cannot be ‘American’.

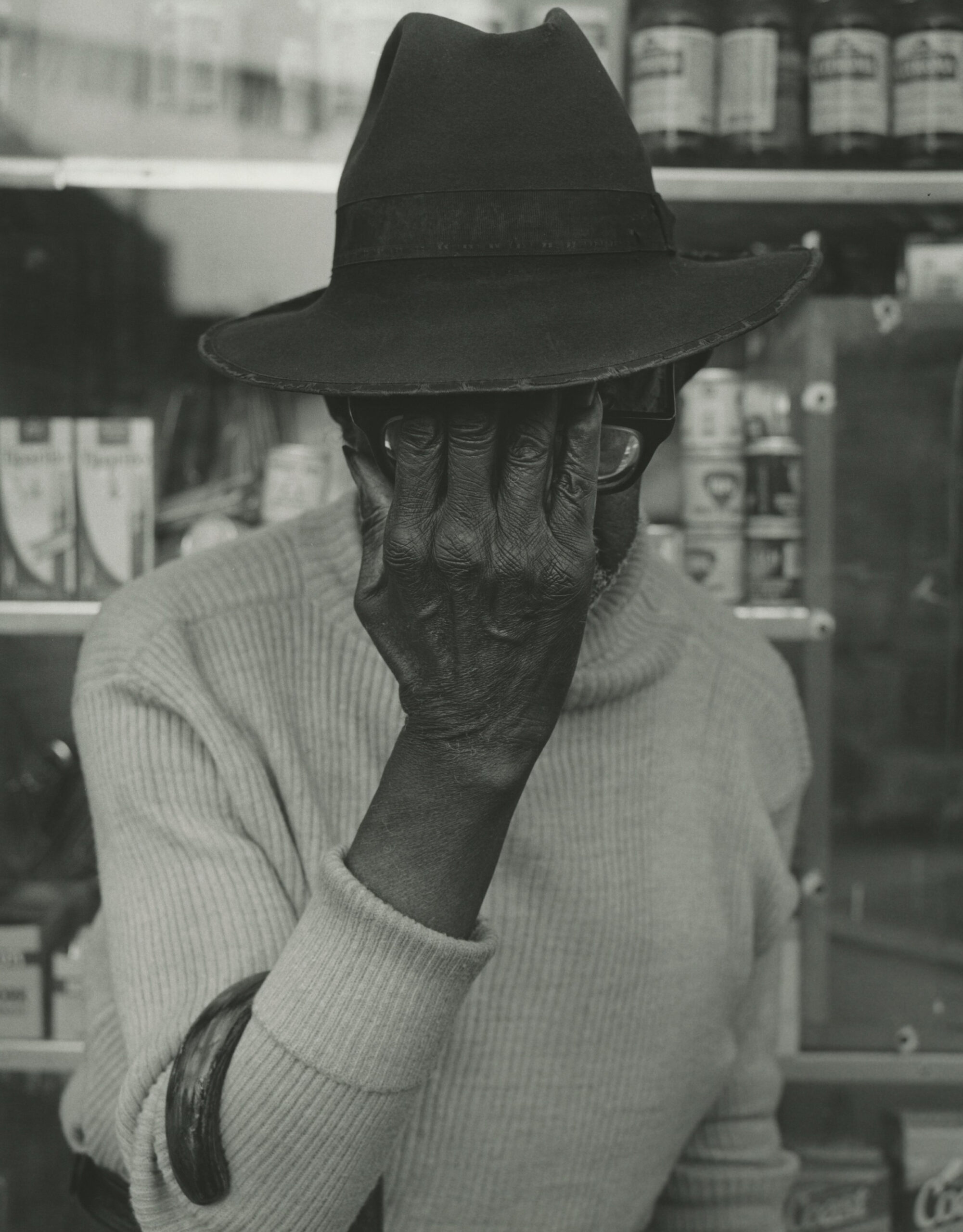

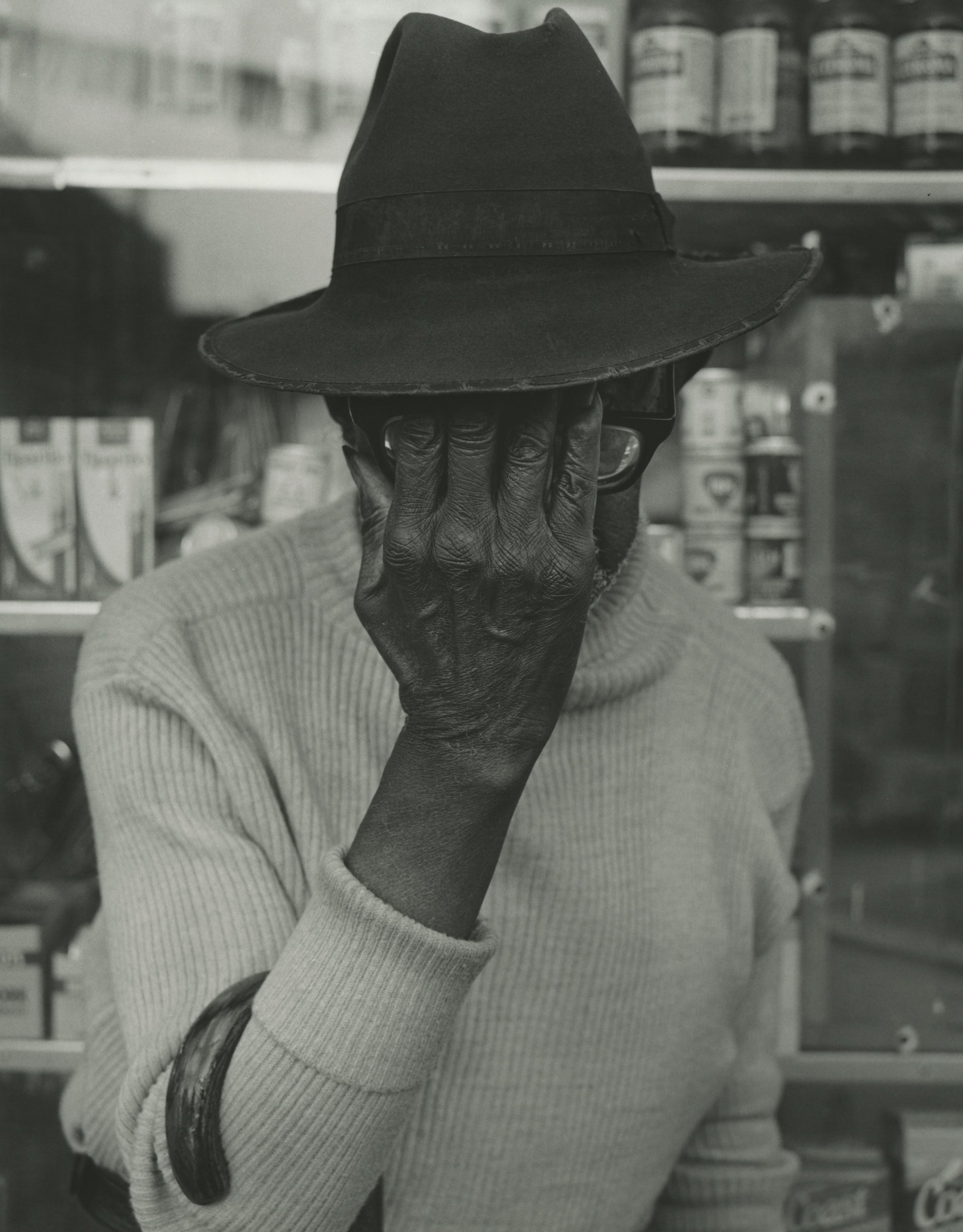

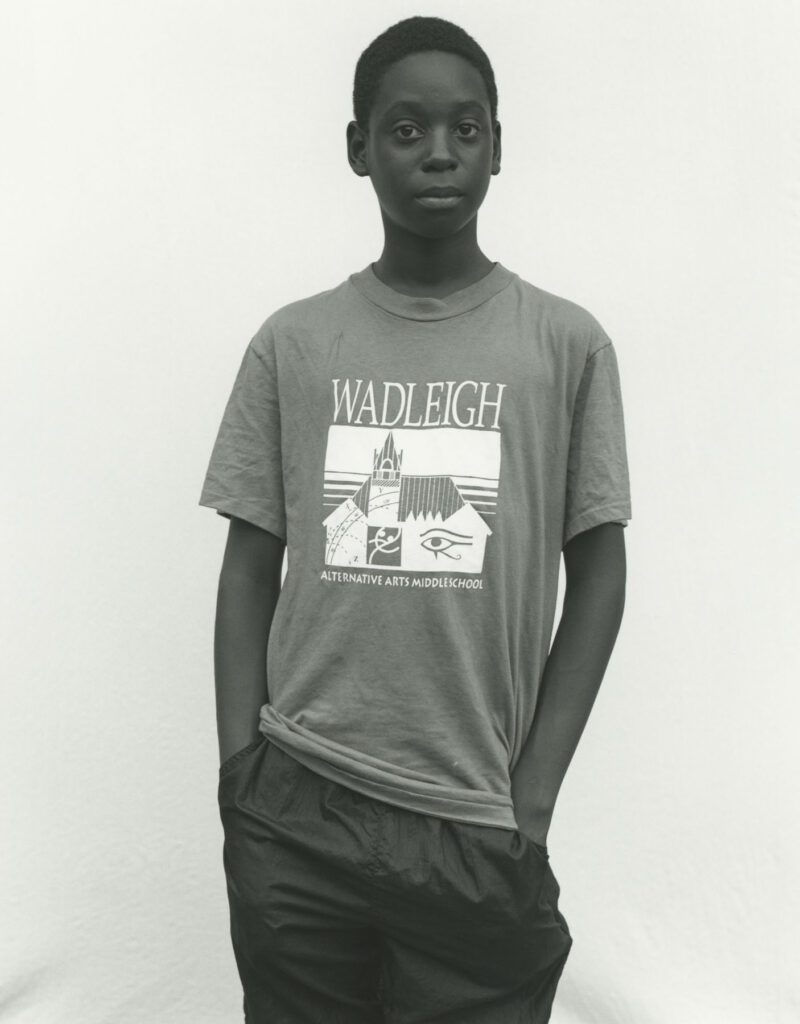

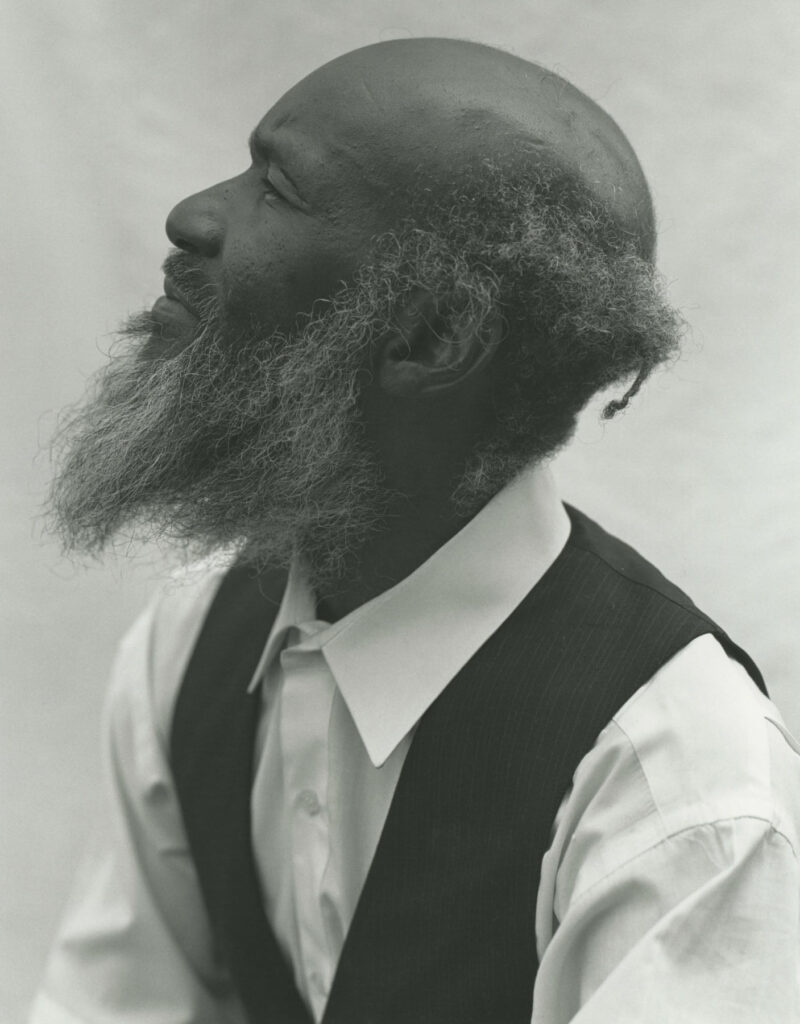

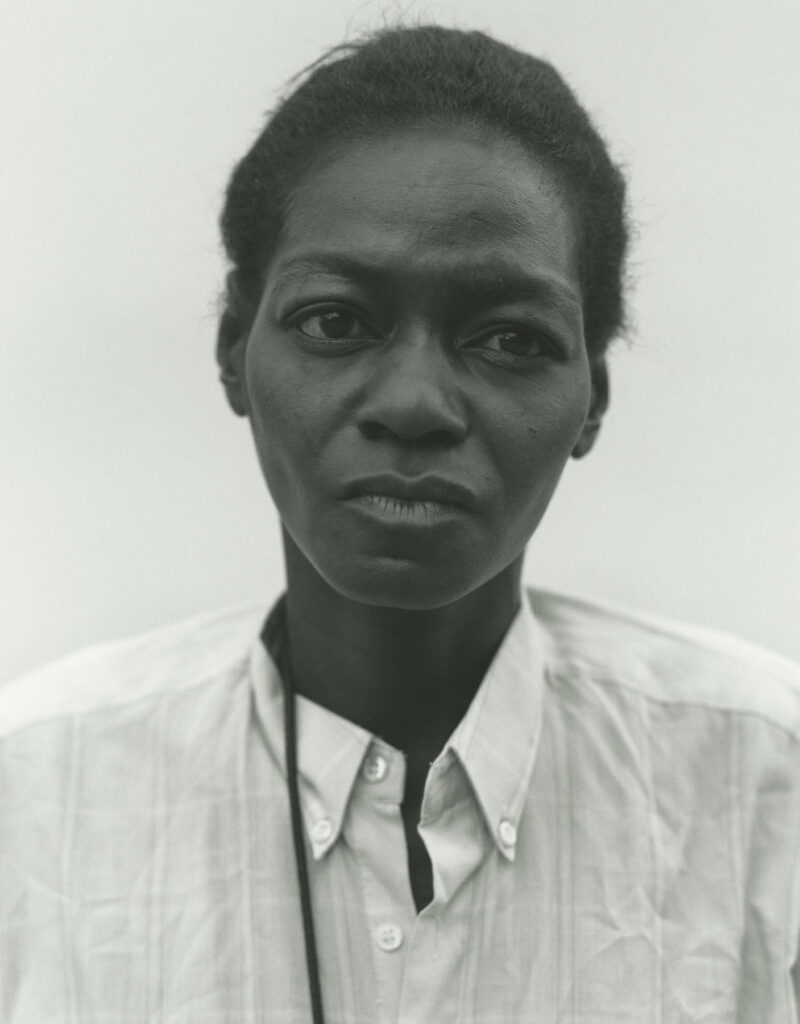

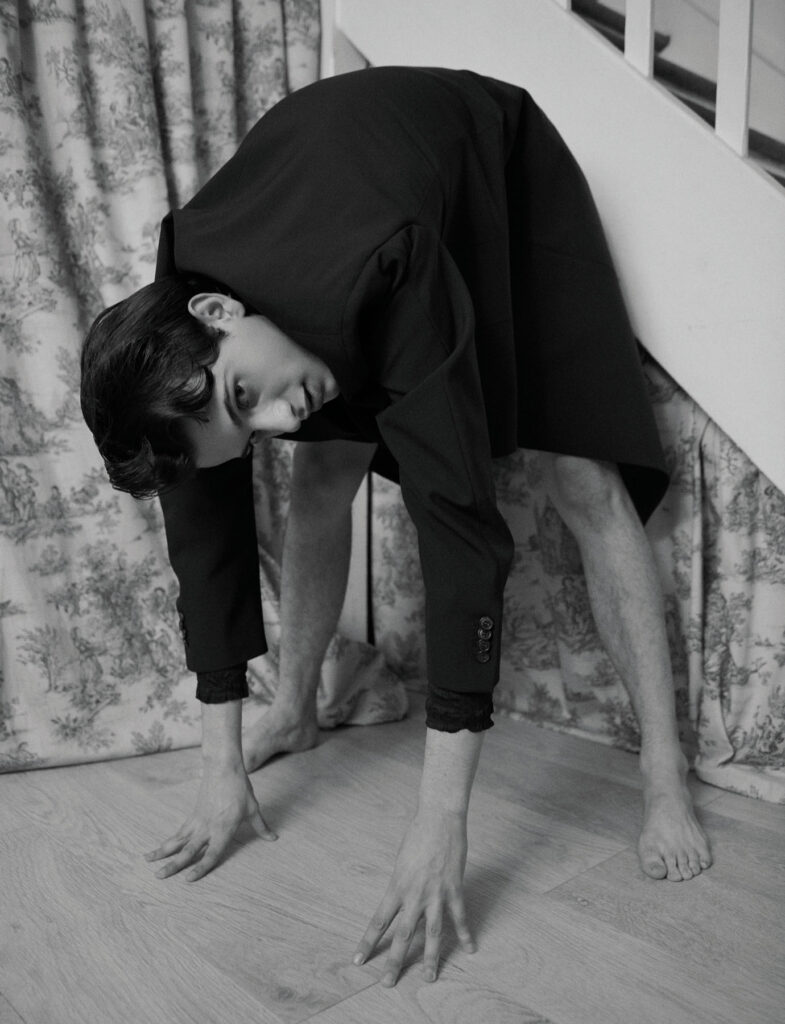

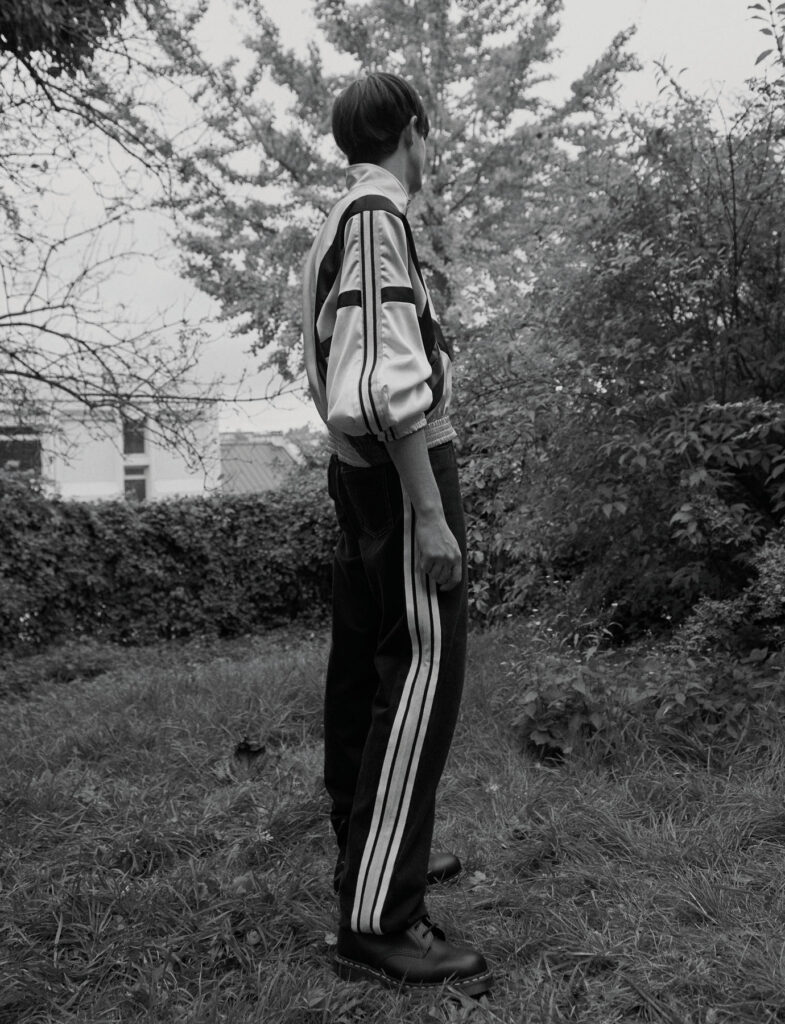

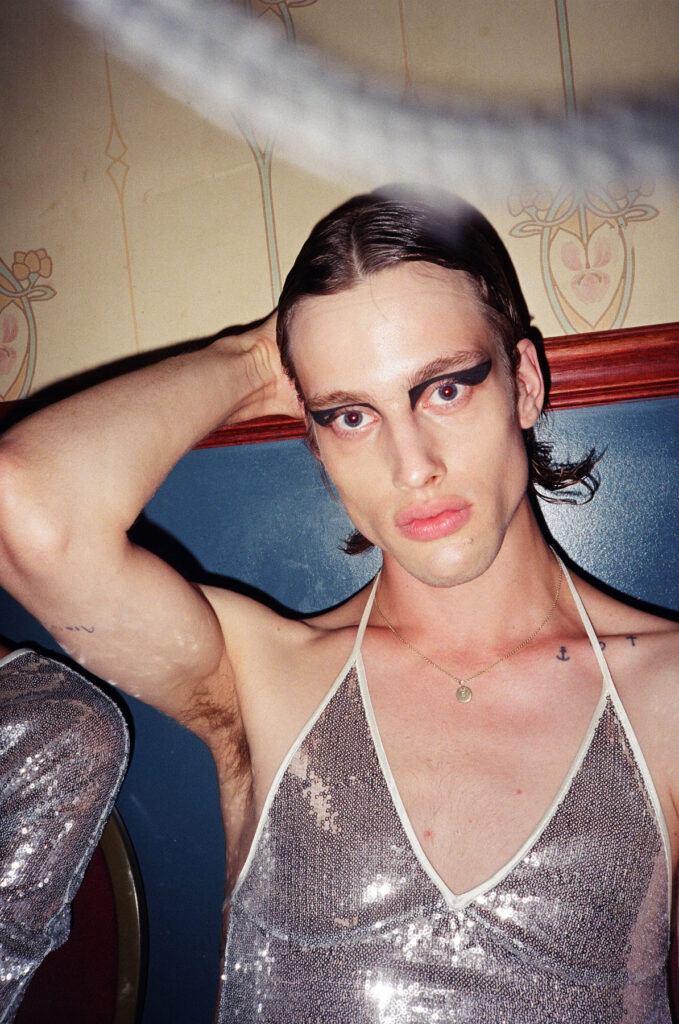

Within this context, the photographer Marie Tomanova presents Young American, a series of portraits of young people in New York – in which their attitude, youthful fearlessness and ambition trumps established connections to the United States. Tomanova, herself, is not American by birth, having moved to North Carolina from the former Czechoslovakia in 2011 to work as an au pair. Since then, and having ended up in New York, the photographer has built up an oeuvre of work that addresses and unpicks notions of identity, gender and displacement.

Turning the camera on herself at times, Tomanova’s self-portraiture is an attempt to discover a sense of belonging amongst the unfamiliar landscape of American soil. In her images of others – people that she has approached at show openings, in the street, or found via Instagram, that make up Young American, Tomanova captures the same sense of intimacy that is felt in her self-portraits. Shooting one-on-one, the series offers a captivating insight into life in the transient metropolis of New York, from a perspective that hinges upon the hopes, dreams and ambitions of self-defining Americans.

NR: Where did the idea for Young American come from?

Marie Tomanova:About a year ago, I was having brunch at my favourite café, Mogador in East Village, with the art historian Thomas Beachdel; we were discussing my work and came up with the idea of the show based on a portion of my work, which he would curate. From there, I then specifically began to shoot more portraits and we mixed in older work with the new. I started to photograph portraits about 3-4 years ago and I did the last shoot just two days before the opening.

NR: How has your own experience in America shaped this series, and your work in general?

MT: I came to the US in early 2011, and I thought I’d stay for six months, a year at the most. It’s been 7 years now, and I consider NYC my second home. There have been tough times over the years – moments when I hit rock bottom and didn’t have family around to help. I cried, feeling helpless, homesick and considered running back home… But that’s all part of life, and I always try to find the positive side of things, even when it looks like there are none. For me, America is a place where things can happen if you work hard and have lots of grit. I fell in love with discovering new things and who I am whilst being so far from friends, family and my comfort zone, and this is all reflected in my work. Young American is my portrait of “America”, in terms of how I envision it as an immigrant and it depicts the America I feel that I belong to.

NR: As someone coming to the US from the Czech Republic, how has this shaped your conception of the ‘American Dream’ – compared with people who’ve lived there their entire lives?

MT: I was born in communist Czechoslovakia and remember the long lines for tangerines and oranges that were only available over Christmas. My parents couldn’t travel and, after the Iron Wall had fallen, we went to West Germany for the first time. I remember everybody staring into the stores, at all the food options – all the cheese and produce selections that we had never seen or had. This oppression shaped the idea of the American Dream as a giant promise of Levis, Coca-Cola and the land of opportunity. When I was a teenager, I used to obsessively watch bootleg DVDs of Sex in the City and I was in love with Carrie Bradshaw’s world. It was nothing like I had ever seen before and I based a lot of my ideas about America on that. After coming to NYC and living here for a while, I realized that it was totally naïve idea, and I am glad that there is “more” to it.

“I cannot say how people who have lived in the US their entire lives feel, but it seems to be, at least now, a very divided place – there’s a struggle for true equality and tolerance.”

NR: What do you think is the appeal of ‘America’ for youth culture?

MT: America meant a lot of things to me (as someone coming from another country) from equality, opportunity and the idea of American Dream. I think the answer is particularly well stated in curator Beachdel’s show statement: “Marie Tomanova’s Young American… celebrates the freedom and identity of the idea of an “America” still rife with dreams and possibilities, hope and freedom. Her images, direct and without artifice, confront us with the power and beauty of people simply being, the young…just being. And in this just being is the essence of unity, love, and acceptance.” I could not agree more with this; I came here for equality and to be who I am.

NR: What impact have the interactions with youth in NY as part of this series had on you?

MT: I feel very inspired by young people and it is always exciting to hear their stories and dreams and the reasons they came to NYC. Some of the kids are native New Yorkers and that is also fascinating to me. I love to hear their life stories of growing up in the city. NYC youth culture, and youth culture in general, is vibrant, fearless and radiant – and it has a strong voice. It has been a great journey for me to have the opportunity to connect with so many amazing people, to learn from them and to see so many new perspectives on life. I have learned how to listen to people better and how to stand up for myself. This series is about “Americans” who are not defined by their passport or visa; instead they are defined by having hopes and dreams – I relate.

NR: Do you think that Young American highlights an alternative type of community at work that transcends a traditional understanding of how people come together?

MT: While I do not like the phrase ‘alternative community’ too much, I think it is true, and I hope, that the youth are a strong community and have a voice that will shape the future. In the US, it is so easy to focus on oneself and the consumer culture, and forget that people have to stand up and stand for something. It inspires me to see so many young people standing up and having a voice – they are strong and express how they feel. They demand to be heard and they demand to be treated a certain way. They are unafraid of being who they are and this is extremely important and a critical part of Young American.

NR: What role does the human form play in your work, and how does this change depending on what you intend to convey – in terms of your own body [Between Flowers, Rocks, Trees and Self] to up-close shots of people’s faces in Young American?

MT: In a way, it’s not that different. My self-portraits in nature are about identity, displacement, celebration and trying to connect to my youth growing up in the forests of Mikulov. When I came to the US, those memories were all that I had, and I struggled to find my identity in a new country. On reflection, this was me trying to fit into the American landscape, or to find my place in the American landscape. And Young American is very much the same idea of trying to see how I fit in the American society.

“The portraits are really of them, me, and us. We are all in their eyes. We are human.”

NR: How has the format of photography opened up the possibilities of expression for you?

MT: I love taking photographs. I really love the process of looking through the little view finder of my Yashica T4 and concentrating on the moment before I press the shutter. It’s just the fact that I can shoot anybody I meet and really capture them in their own way. I’ll meet people at openings, or on the subway, or I’ll see somebody I want to shoot on Instagram, and what photography does is allow me to actually create a real connection with them, and capture that in the photo. In a way, photography has really allowed me to be me, and I found out who that is through this process. It has been magical.