Fighting The Good Fight

When some people hear the name “Denzel Curry,” they think of the explosive chorus of his high-octane hit “Ultimate.” Others may think of his viral music video for «Ricky»––which recreates the backyard brawls Curry attended in his hometown of Miami––or the fact that he toured with superstar Billie Eilish, who has proclaimed Curry to be one of her favorite artists. The rapid conclusion that can be drawn from his flashiest achievements––that Denzel Curry is a great rapper––pales in comparison to the one drawn by those who have dug deeper into his complete body of work. When you truly connect the dots of his career, you are confronted with a portrait of an artist who has made a truly massive contribution to the development of hip hop in the past decade.

Curry, who began writing rhymes as a child, was still in high school when he became a part of SpaceGhostPurrp’s infamous collective, Raider Klan (stylized RVIDXR KLVN), whose gritty sound, gothic aesthetic and hieroglyphic style of writing influenced an entire generation of rappers and headlining acts. Curry was also a member of the creative cosmos who helped establish both Soundcloud and South Florida as one of the most exciting breeding grounds of underground and experimental rap in the 2010s. He helped transform a digital platform into one of the most consequential genres of its time: Soundcloud rap.

On each new record, Curry reinvents himself. He evolved away from his original claim to fame, the aggressive, speed-rap of Imperial (2016) and into a more confessional and vulnerable terrain with Ta13oo (2018). Last year, he conquered boom-bap with Melt My Eyez and See Your Future––an album that revives the beats and politically minded rhymes of 90s hip hop. Even though Melt is his first record that actually sounds like Nas, De La Soul and Wu-Tang Klan, Curry’s high-level wordplay and amplification of social issues have long embodied the spirit and soul of «golden age» hip hop artists, who viewed their music as a means of political resistance. Critical issues like criminal justice reform, systemic racism and police brutality are deeply and tragically embedded in Curry’s life and creative output. Both his classmate, Trayvon Martin, and brother, Treon Johnson, were murdered by the police, in 2012 and 2014, respectively.

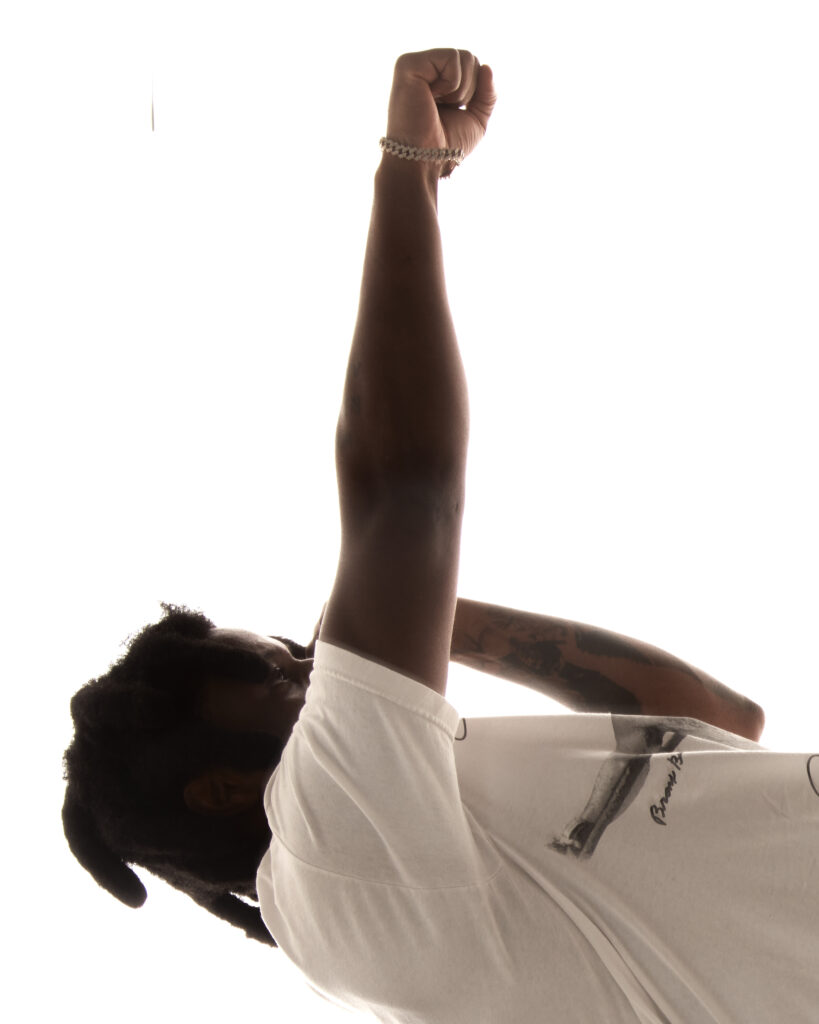

The art of the battle is a theme that connects Curry’s childhood with his greatest sources of inspiration: anime, video games and martial arts. Conflict is at the center of his musical oeuvre, which sheds a powerful light on the harrowing realities of being Black in America––and the internal dialogues of someone at war with both the world and themself. And despite his many accolades, Curry’s status in the music industry today is the byproduct of a constant fight to be seen, heard and respected. With his pen as his sword, Curry has proven himself time and time again to be a formidable match for any opponent. Denzel Curry is, above all else, a fighter worth betting on.

Cassidy George: I know that you’re really devoted to your Muay Thai practice. Is that how you started your day?

Denzel Curry: I can’t do Muay Thai today. I fucked my neck up yesterday doing calisthenics because I didn’t warm up. Now I have to chill.

Cassidy George: Is Muay Thai so embedded in your routine that not being able to practice makes you feel «off»?

Denzel Curry: Yea, plus I get fat really easily! Normally, I spent most of my time on the couch and eating. I still plan on getting sweaty today though––but at the sauna.

Cassidy George: Earlier this summer, you released a new single «Blood on my Nikez.» It’s a big shift in sound from your last album, Melt My Eyez and See Your Future. Is this the start of a new era for you?

Denzel Curry: This isn’t a new beginning, I just wanted to have fun with my music. Melt is my perfect project. It’s the best thing I’ve ever put out, but I don’t feel like it got the recognition or appreciation that it deserved. Everyone is just concerned with numbers and what goes up at shows. So many other artists, like Kenny Mason, also came out with impeccable projects last year. I feel like they were swept under the rug because they weren’t «popular.»

Cassidy George: Is that a difficult or intimidating place to be in, as an artist? What comes after a magnum opus?

Denzel Curry: I plan everything far in advance. When I was making Melt, I already knew what the next project would be. It may not come out now, next week or next year––but it will be released at some point. I just need to flesh it out a bit more. Until then, I’m just dropping shit that’s fun. Melt set a really high standard for me and I won’t release another album until it’s 100% ready.

Every track that I write, I write from my feelings. Back in the day, a lot of my feelings were just anger and sadness. When I came to LA and was making Ta13oo, for example, I was in a new environment and there was nothing around me. I experienced a little bit of depression. Making that album…it was very internal to external. I had so much more fun making Melt because the stuff I was talking about, like therapy, and just the soundscape I was going for––it took the burden off of my shoulders. Once it was well received by the public and critically acclaimed, people were like: «Wow, I didn’t know he had this in him!» The upside of that is that it caused a lot of new people to want to work with me because they saw a new side of me, beyond the «rah rah rah» of Ta13oo or Imperial.

People are so wishy-washy though! When new things come out that they like, they go back into the old stuff and are surprised that it’s good. Many people didn’t even listen to those records because they expected just one thing from me. That’s the narrative I’m trying to change.

Cassidy George: What was the narrative, specifically? And what new narrative are you trying to construct?

Denzel Curry: That I was a one-trick pony and that I’m not versatile. I ended up proving on Ta13oo that I was hella versatile. My true fans know that in each project I do something different and that I always nail it. Of course, people will always choose not to listen––but that just comes down to preferences. I can’t let that kind of thing get to me…but I let it get to me. You know what I’m saying? I’m human. It is what it is.

Cassidy George: I think one of the greatest pleasures in life is proving people wrong.

Denzel Curry: That’s my greatest revenge! It’s the best thing I’ve ever done and the only reason I’m successful. I get good at so much shit just to spite whoever said I couldn’t do it and all of the people who said «stick to one thing!» I’m like, «Okay, see you next year!» I remember there was this guy back when I was getting into rap who would always ridicule me. I just never stopped rapping. One day «Threatz» blew up and this man hit me up again and said, “let me get on a track!” I was like, «ain’t you the one who said I couldn’t rap? You wanna be cool now? Fuck that!”

Cassidy George: Your parents supported your rapping from early on though, right? Who was it that didn’t believe in you?

Denzel Curry: Some people thought it wasn’t possible because they didn’t see it.

Cassidy George: By «it» do you mean your talent? Or potential?

Denzel Curry: Yea, but everybody sees it now because they can’t avoid it. People only see things when they’re unavoidable.

Cassidy George: When I heard Melt and saw your music videos for “Zatoichi” and “X-Wing,” I immediately thought of the Wu-Tang Klan. In many ways, you are continuing a long tradition of rap that is influenced by Asian culture. Any thoughts about why there is so much synergy between those two worlds?

Denzel Curry: Wu-Tang’s 36 Chambers and Raekwon’s Only Built 4 Cuban Linx… those albums were essential listening for me back in the day. As far as culture, I grew up watching Toonami. I also watch kung fu movies, but anime was what really did it for me.

Cassidy George: Battles are an ongoing theme in your history, your hobbies, your music and your message. On Melt, the battles you rap about are both internal and systemic. Who or what, if anything, are you battling right now?

Denzel Curry: The same thing that I’m battling now is the same thing I’ve battled since the day that I was born: my demons. I am always translating that into my music. I knew I had to take martial arts seriously because I needed to reach a level of fearlessness, where you can go up against anybody and be unshaken.

Cassidy George: Even yourself?

Denzel Curry: Of course. You can be your own worst enemy.

Cassidy George: Is that what you were working on in therapy?

Denzel Curry: Yea, but I don’t go anymore. I just want to live my life without feeling like I’m walking on eggshells. Therapy only increased my anxiety, funnily enough. It helped a lot, which is everything––but it felt like I was being told what to do. I just want to live my life with no ifs, ands or buts.

Cassidy George: Wow. Eggshells? Really? Isn’t the whole idea that you are free to share and say anything without judgment?

Denzel Curry: I didn’t feel it during sessions, I felt it when I walked out of them. I felt like I had to snitch on myself constantly. Now, I’ve done the work. I’m good with myself and I can make the right choices. I don’t want to go in there and get all of the answers.

Cassidy George: You strike me as someone who doesn’t respond well to being told what to do.

Denzel Curry: Shit, man. I’m an Aquarius! We’re known to rebel.

Cassidy George: I’ve always thought of you as «my favorite rapper’s favorite rapper.» But which artists are you most excited about right now?

Denzel Curry: Paris Texas, Kenny Mason, Destroy Lonely, Ken Carson, JID, Jasiah, Midwxst. A producer named Sophie Gray and an artist named Sherelle. Also Kaytranada, PLAYTHATBOIZAY, Amber London.

Cassidy George: Is there anything that all of those people have in common?

Denzel Curry: All of them have this appeal that came from the underground. There’s nothing industry about it, it’s real.

Cassidy George: That’s also been a theme in your career.

Denzel Curry: Yeah, it’s a battle. It’s not about what you know, it’s about who you know. It gets exhausting because you think that these people should know by now what you’re capable of, but some people are scared to get outshined and others don’t see the value in helping you.

Cassidy George: Are you good at playing the game?

Denzel Curry: No, but I always stay myself when I am playing it. I just think it’s best to treat everyone with respect and dignity.

Cassidy George: What frustrates you the most about the industry in 2023?

Denzel Curry: Labels and the people that run them. When I say I want to work with another artist, they say «Sure, we’ll get to it”––and never get to it! It’s all fake. If they don’t see what you have to offer at that moment, they put you on the back burner. Everything I put out is quality and yet I am always questioned about the things I do. Right now, I’m focusing on getting my singles right. With albums, I’m playing the long game. I want to make sure everything I put out is timeless.

Cassidy George: How do you do that? By ignoring trends?

Denzel Curry: No, you have to pay attention to trends. You just can’t ride them all the way. You take bits and pieces. Good artists copy. Great artists steal. But you can’t steal something new from somebody that’s newer––that’s fucked up. I’d rather steal from old shit and make it new. Think about it: you couldn’t have Jackie Chan without Charlie Chaplin and Bruce Lee.

Team

Photography · Geray Mena

Styling · Sophie Gaten

Hair · Chrissy Hutton

Grooming · Alice Dodds

Location · The Rubicon London

Special thanks to August Agency