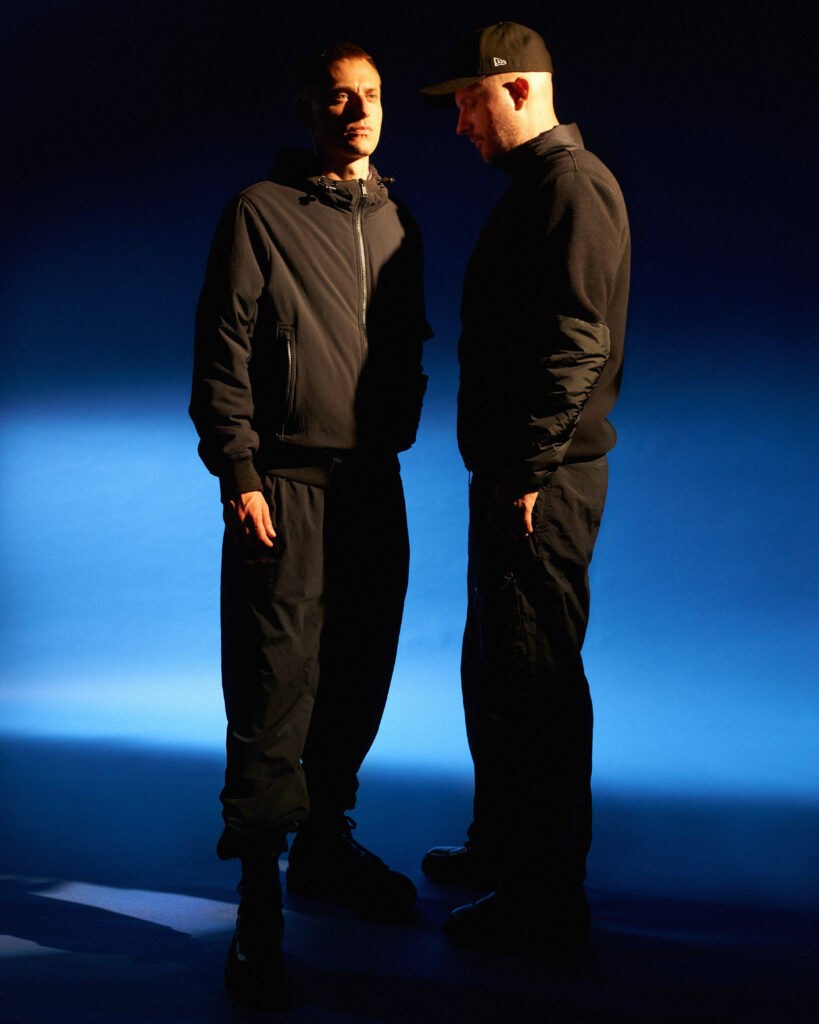

In Love Again

NR presents Track Etymology, the textual corollary to nr.world’s exploration of contemporary soundscapes: A series of short interviews delving in the processes and backstories behind the releases premiered on nr.world’s dedicated platform.

In Love Again and Five Years feel quintessential Mumdance but at the same time headed towards new territories. Listening to the tracks I had two reactions: Bobbing my head as a timid attempt to dance in the studio I was in, and reflecting on how the UK sound continuum, something you have been rightfully associated with, is intrinsically hybrid and continuously moving. You are now almost 15 years in the game, a veteran, if I might say so, but you continue to experiment and evolve your body of work. You have been close to it in so many ways throughout more than a decade: What would a Mumdance definition of the UK sound be?

I’m happy you enjoyed the music. It’s actually been quite a challenge to wrap my head around how to make happier, more optimistic tracks and incorporate them into something that matches my aesthetic. But that is part of the journey – I’m glad you picked up on the fact that I have always tried to evolve and challenge myself with every release. I’ve never really sat down and thought about the reason why, apart from it just always felt like the natural thing to do. But as I sit here and think deeply about it, it amuses me to realise it’s actually something that I latched onto at a very young age from my parents talking about Madonna and how she always reinvented herself, which as an idea fascinated me. I think constantly experimenting with my sound has been something that overall has created challenges career-wise, as a lot of people haven’t really known where to ‘place’ me. But at the same time, I feel happy that in my own small way I have broken some new ground, added to the canon, and helped to slightly shift the paradigm and allow newer artists to be able to express themselves more freely with their sounds.

In terms of defining the ‘UK sound,’ it’s an impossible task to encapsulate a whole country’s sound and musical heritage into a few sentences. The UK sound which I enjoy exploring, is underlined by lots of sub-bass and weight in the low end, engineered to play on a big sound system, with complex rhythms, and more often than not, a dark, futuristic mood. Other than that, it’s actually quite a puzzle to define, as the very nature of the hardcore continuum (and the very nature of life itself, in fact) is that it is constantly changing. I could list 500 tracks which encapsulate the UK sound, but as I only have a few paragraphs, I’m going to say ‘Swarm‘ by Doc Scott and ‘I Luv U‘ by Dizzee Rascal are two tracks which sprang directly to mind for me when I read the question.

During the very recent club ‘history’ (perhaps we need more quotation marks as I’m referring to the last couple of years), the idea of a defined musical scene mutated, evolving past geography toward a form of digital ubiquity. The continuous hybridization of sounds and the increasingly international profile of electronic music made things more diverse and, at the same time, more standardized. How do you navigate this paradox?

I don’t think this is a new thing, although I definitely agree it’s been accelerated. Nothing exists in a vacuum. In my mind, the core of any culture is shared meanings; then a lot of the time, further innovation comes from the conversations between one culture being exposed to another, between countries, cities, between people. Baltimore Club is an example that I have always found really interesting, as the first wave of artists like DJ Technics were all sampling breaks from imported rave records from the UK, which in turn were breakbeats that the UK had sampled from imported hip-hop records from the US, processing them and speeding them up. So, it’s this interesting symbiotic feedback loop which created something entirely new and innovative at many different stages of its cycle. This is just a quick example which sprang to mind as I write this, but once you start to recognise it, conversations between cultures play a big part in many innovations in art and music. It really interests me as an idea and is one of the main reasons why in the past I have done a lot of collaborations with artists from around the world and a lot of back-to-back DJ sets with people who are specialists in different genres to me.

In terms of where we are today with technology and culture, increased connectivity has increased conversations and the volume of art being created, which, like anything, has a plethora of consequences that could be deemed ‘good’ and ‘bad’.

«I love being able to send my music all over the world at the click of a button and am fascinated by technological innovation, but I think one downside of the digitisation of culture and the rate at which people digest it today is that a lot of the time, scenes and localised sounds don’t get enough of an incubation period to develop properly.»

In the past, a lot of the UK scenes – hardcore, jungle, drum and bass, garage, grime, dubstep – for better or worse, were all time-limited by the production process of pressing physical vinyl. This had its upsides and downsides, but a by-product was it naturally made things operate at a certain pace, which I think led to a much deeper exploration of sound and embedding of the music within our collective consciousness.

I guess with regard to navigating my own work, although I am very in tune with what is happening in music, art, and the various zeitgeists, I try my best to not focus at all on what my peers are doing, instead just following my interests and focusing on music which provokes a reaction within me, be it emotional, physical, or cerebral. That’s the key to it.

Usually, the jargon associated with musical cross-pollination feels somewhat…violent, almost. The formulation often goes something like ‘Genres bleed into each other.’ However, in your new record, the sounds don’t seem to bleed; rather, they play with each other. I understand that this might sound like mere semantics to you, but due to my professional inclination, I can’t help but fixate on language. This is your second record after a three-year hiatus marked by significant introspection. Are these more joyful, welcoming sounds a reflection of a new era for you? How much of your feelings are imbued in your music?

Yes, I definitely feel like the MD series marks the start of a new era for me – ‘Mumdance 3.0’. I have always referred to my musical activity in waves/eras. The first wave of Mumdance was from 2008 to 2011 when I first emerged and was working a lot with artists such as Jammer & Diplo. I think this was epitomised by my ‘Mum Decent EP‘ and ‘Different Circles – The Mixtape‘ (Both released in 2010). During this time, I was putting out music which had a foundation in grime & the UK hardcore continuum but was strongly influenced by regional music from around the world, especially what was going on in Mexico & Brazil at the time.

The second ‘wave’ of Mumdance started in 2013 after a 2-year hiatus with the ‘Twists and Turns‘ mixtape and was a lot more UK-centric and introspective, focusing on all the sounds which I grew up with: hardcore, jungle, drum & bass, shoegaze, and cross-pollinating it with ideas from my more contemporary interests; techno, and musique concrète – which is the sound which most people today know me for. The idea with that was to completely invert where my influences came from; instead of looking outwards around the world, I looked inward to my upbringing.

With this emerging third wave, as my last wave was very dark in mood, I made a conscious decision to do the completely opposite and try to make some ‘happy’ music and operate within genre boundaries with which I wouldn’t normally be associated, such as filter house. As I said above, it has been a real challenge, but I realise more and more that art is about the process, and this is how I like to spend my time.

In answer to your question, my feelings and outlook on life are definitely reflected in the music I make; they by their very nature are a sum of my experience. MD001 was a transitional record for me, just finding my feet again in the studio, but MD002 definitely feels like something new. For ‘Five Years’, I wanted to make a track which joyously celebrated half a decade of sobriety and the work I have done on myself in that period. ‘In Love Again’ references being back in love with music after a long time away and signals in my mind a return to form – that track really feels like an amalgamation of the ideas from the first wave mixed with the ideas from the second wave.

The Mumdance Archive is impressive. It stands as a testament to how, throughout your career, you have witnessed the evolution of the clubbing world and evolved alongside it. You have worked as a sound engineer in commercial settings, curated parties and events, delved into the purest underground scenes, and navigated more mainstream waters. After a hiatus, you are now 1 year back and seemingly fresher than ever. What did clubbing and electronic music mean to you then, and what do they mean to you now?

I’m very proud of the MD Archive; it took me a long, long time to put together, maybe like 18 months – it was my pandemic project. All my work was so disorganised and spread out across a number of old computers and hard drives, all in different locations. It was a very long and tedious project to go through everything and make sense of it, but at the same time, it was very timely for me as it was a period when I was feeling very lost. It helped me remember who I was, where I came from, and what I had achieved.

What I like about the archive is that when you see everything all together – the mixes, music, and interviews – you can see the progression in my sound and the progression of me as a person and artist. Also the aforementioned waves which have come and gone, and the themes that have stayed present throughout. I think a lot of people think I just play and create music randomly from disparate scenes, but there is a lot of thinking behind it and there are moods and themes which run through it all. Having everything in one place, you can really see it.

Another reason I put the archive together was trying to take power back from social media companies and big tech; so much digital culture has been completely lost over the past 20 years due to websites and hosting services going down or out of business. Which is both sad and scary.

An amazing thing about the archive is that it has evolved to become a platform from which I can broadcast radio. As a result of that and in tandem with Discord, a whole community has organically sprung up. When I do radio broadcasts, all the listeners meet up in the discord and there is a really buzzing live chat which has developed a new level of interactivity between artist and audience which I honestly have not seen anywhere else. There was one time where I hadn’t had any dinner, so listeners sent a pizza over to my studio live on air so I could stay and do a longer show & another time where when I got to the studio the CDJs weren’t there, so listeners just sent me their music live on air & we just all listened to each others music for a couple of hours; there have been some really beautiful experiences & I can comfortably say that the MD Discord is one of the friendliest places on the internet. Everyone is so kind, funny and helpful there. Social media always just upsets me, and the discord server is a complete antidote to that.

Electronic music still means as much to me today as it always has, I’ve accepted that I am here for life. I’m not out clubbing every weekend like I was when I was younger, but I stay connected and if something is interesting to me I will make an effort to go and experience it first hand, even if it means saving up and traveling to another country, which is something I have always tried to do throughout my life;

«I’m a firm believer that you can’t form a proper opinion on something unless you have experienced it first hand.»

I want to give a big shout out to my friend Chris Yaxley who gave a lot of his time and energy helping me code the archive. He is one of my best friends from childhood; we started DJing and buying records together when we were 12, so it was really nice to revisit all this with him.

5MD002 is out on your new label, MD Dubs. How does MD Dubs differ from Different Circles? Why did you feel the need for a different outlet?

MD Dubs serves as an outlet solely for releasing my own music with a relatively short turnaround time, whereas Different Circles functions as a highly curated platform for showcasing other people’s music. I believe MD Dubs also signifies a general levelling up at every stage of my production process. I can honestly say that the tracks on MD001 and MD002 represent the best music I could have possibly made, utilising the best equipment available to me at that specific moment in time. The tracks are mastered at Abbey Road by Alex Gordon, who truly understands my vision and possesses an amazing ear. Recently, I’ve begun sharing my studio with a mix engineer named Alex Evans, and we’ve naturally started collaborating. As someone solely focused on mixing as a career, he is a master of his craft and adds a dimension that I could never achieve on my own, teaching me so much in the process. In previous stages of my career, I handled everything myself, but this time around, I’m trying to explore a different approach.

Whenever I start doubting myself and if my output is good enough (which is quite a common occurance), I remind myself that I spent countless hours working on it, revising and refining it to the best of my ability within the time frame allotted. It’s been mixed by a Grammy-nominated mix engineer and mastered at Abbey Road. It truly represents the best I could achieve at every stage of the process.

«As I wrote the shoutouts for MD002, I was struck by how many people played a part in bringing the EP to life and creating the visual world around it. I think thats a beautiful thing.»

You stated that each MD Dubs release will be accompanied by a Sholto Blissett painting. You always referenced a wide plethora of extra-musical elements in your work, one of the most dear to me being William Gibson. Besides musical influences, what drives and inspires your ethos as a creative the most?

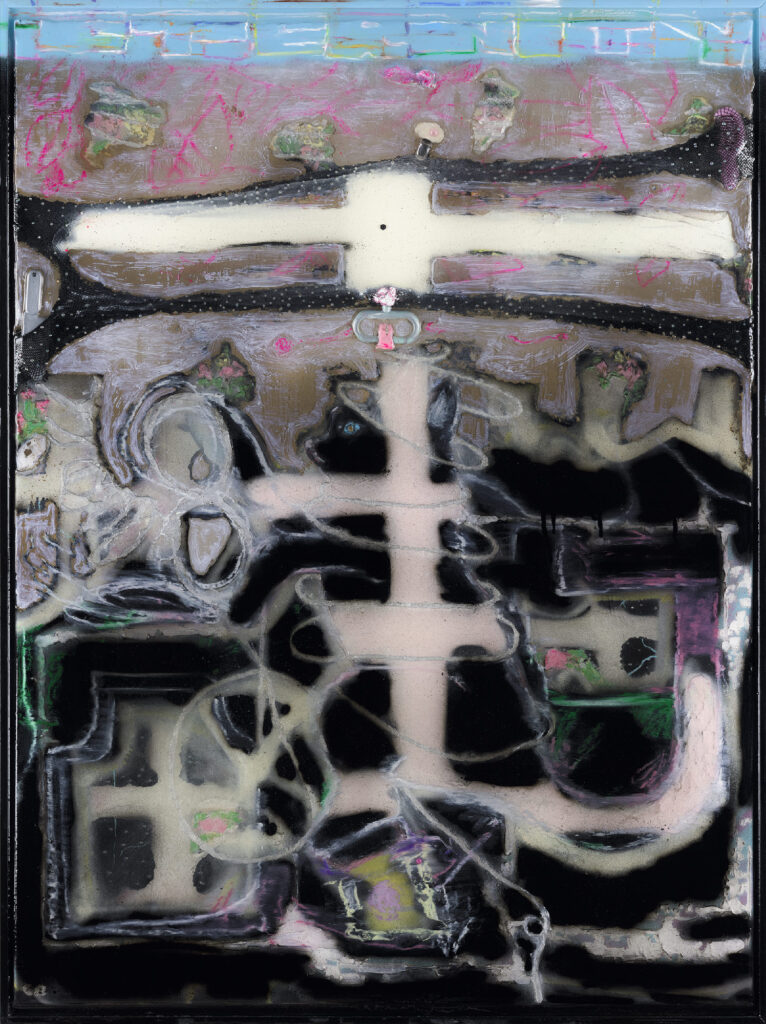

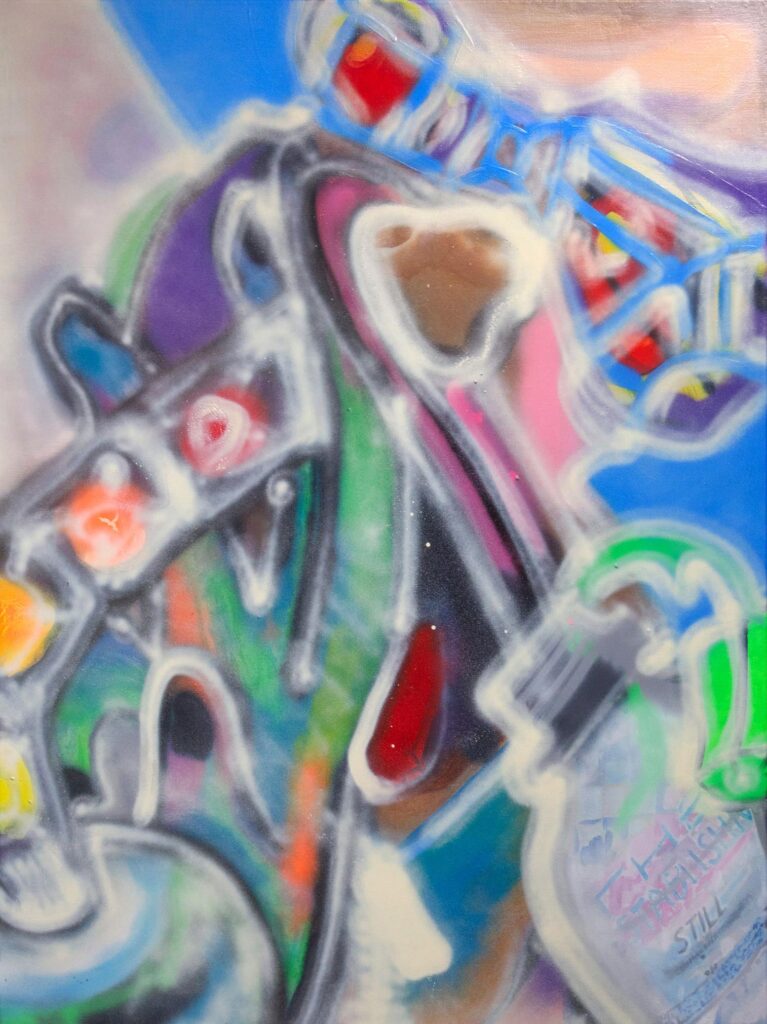

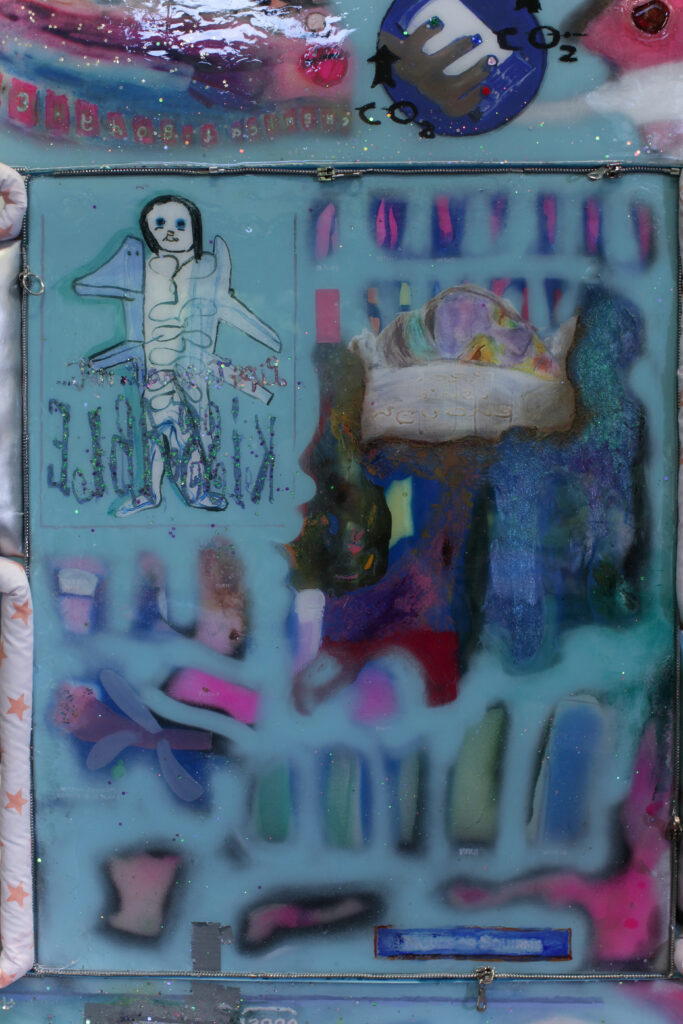

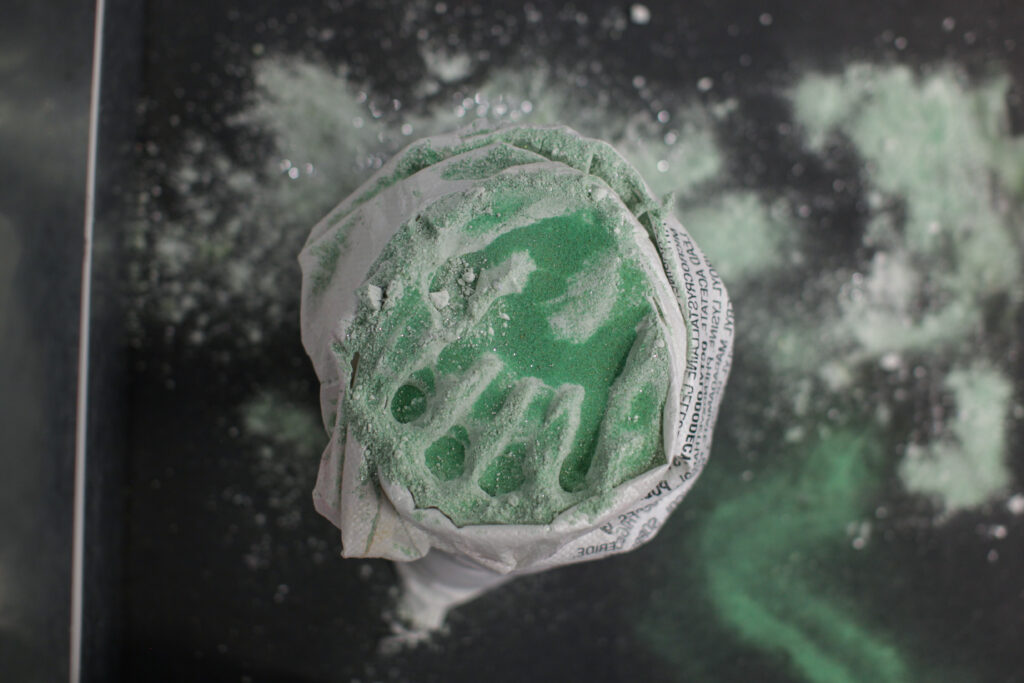

I’m really happy to be collaborating with Sholto Blissett; His paintings remind me of a mixture of Fredric Edwin-Church and Giorgio de Chirico, they resonated with me from the very first moment I saw them. I always make it a point to attend graduate art shows to see what the new generation is creating each year, and that’s where I first encountered his work, pre-pandemic. A few months later, during the pandemic, his art was still on my mind, so I decided to commission a painting from him. He cycled over and personally dropped it off, and we’ve stayed in touch since then. When I thought about what I wanted to do with the MD series, I thought of his artwork immediately. I believe it really complements and encapsulates what I’m trying to achieve with the series. Working with him has felt natural and organic, and I love that each artwork actually exists in the real world. It’s been amazing to see his career blossom, and I am certain it will continue to do so.

Of course as a musician I get very inspired by other musicians, which is part of the reason why Logos and I wrote the track “Teachers” – to express our gratitude to those who have influenced us. Outside of music, I draw inspiration from various sources; books and literature are definitely among them. Reading a book is like ‘updating your software’ and expanding your worldview. There are authors who have been highly influential to my work as an artist. William Gibson, for sure, and more recently Jorge Luis Borges (I’ve literally read everything he ever wrote), Gabriel García Márquez, and, on a deeper level, Thich Nhat Hahn. Reading is akin to travel and art; it exposes you to someone else’s way of thinking and doing things.

Visual art and art theory are very influential to my work on a conceptual basis. Minimalism is a core theme that runs through all of my discography. I come from a working class background and have no formal education in art (or in music, for that matter), I’m completely self-taught through reading and experiencing as much as possible firsthand. Conceptually, El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich, and Agnes Martin have influenced my music by embodying abstract minimal art stripped back to its core, often without any sort of reference to the real world. This influence extends to the graphic designers I work with. I spend a long time discussing art and design Alex Gross and Lucy Wilson at All Purpose studio, who handle all my design work & have become good friends. This time around, there was a conscious decision to convey a lighter mood with the graphic design while still keeping it super minimal to reflect the music. If you look at the artwork for Radio Mumdance Season 03 series, you’ll see the influence from Lissitzky and Malevich is very apparent.

I believe that while conceptualising, theorising and engaging with art in its various forms is enjoyable, there has definitely been an over intellectualisation of dance music in recent years, which can become tedious. I admit that I’ve been guilty of this at times, but I always prioritise keeping things fun above all else.

«I want my work to represent a collision of high and low brow culture.»

DJing is a somewhat conversational discipline. On one end of the club there is you, your taste, your sound, on the other there’s the audience, with their vibes and moods: Different audiences lead to different conversations –DJing happens in between. Does your experience as DJs and these conversational elements of the discipline inform your music production, or is producing the space where you reclaim total autonomy for where you want your sound to go?

Nine times out of ten, I create music with a focus on the club in some shape or form. I always ensure my tracks are highly functional and easy to mix, with DJ-friendly intros and outros. However, everything in between is always centred on innovation and communicating something in a unique way. I try to take the accepted paradigm and bend it into a strange shape, so it’s recognisable yet feels alien. I’ve mentioned in past interviews that I try to make my tracks like firework displays for a sound system. I think this ethos is particularly evident in ‘In Love Again».

In terms of DJing, lately I’ve been focusing on 4-deck extended sets. When I began DJing, I only did one-hour sets with two decks, but now I prefer longer sets—five, six, eight, even ten hours. I have a lot of music I want to share and a lot to communicate, so longer sets make more sense for me. It’s also very gratifying to soundtrack an entire evening for people who are strapped in and committed to the journey. Learning to use four decks has been very enjoyable as well. If you listen to my DJ or radio sets, you’ll know I don’t use any sort of syncing. (Let it be known that I have no problem with people who do; I just find syncing more confusing than enabling) However, I also enjoy the fact that at any moment, my set can fall apart in quite a dramatic fashion—and quite often it does.

«But that’s what’s human about it, and I’ve learned that the human element is what everyone truly appreciates the most.»

Last question: What more do you have in store for 2024? Something you are particularly excited about?

In the past, one of my weaknesses has been inconsistency. I tended to work in frantic bursts, and then burn out completely. This time around, I’m aiming for a calm and consistent output of good music. A marathon rather than a sprint. I plan to release four MD Dubs releases this year, one every three months. Additionally, I’ve been collaborating with an immensely talented choreographer named Zoi Tatopoulos We have some very interesting projects in the pipeline…

Finally, I’m pleased to announce that Different Circles will be returning in 2024. We are in the process of putting together a compilation called ‘Ping Volume One,’ which originated from an in-joke with the Discord community. This joke evolved into an episode of ‘Radio Mumdance called «The Ping Report» and now it’s blossoming into a conceptual compilation, marking a new chapter in the label’s lineage.

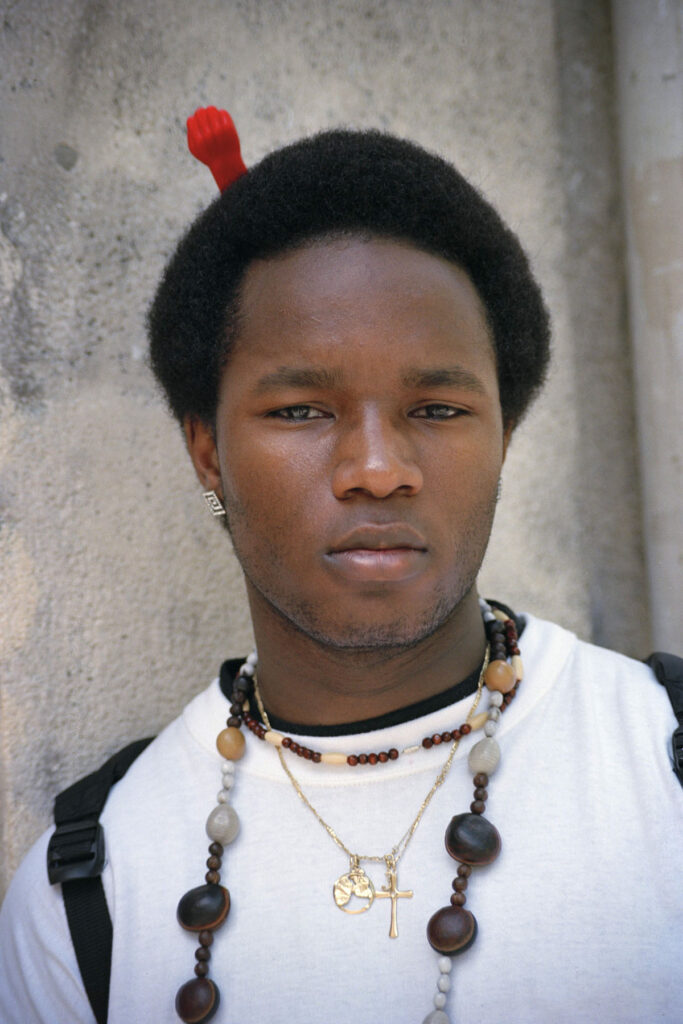

Interview · Andrea Bratta

Artwork · Sholto Blissett

Photography · Sam Hiscox

Pre-order the digital album here

Follow Mumdance on Instagram and Soundcloud

Follow NR on Instagram and Soundcloud