It’s funny though, because I eat very differently when I’m there compared to how I eat here, and I think of food in a completely different way. I think London has this immense pressure – there’s this stress to deliver things that are exciting and different all the time, whereas in other places you don’t think of it like that. Instead, you think of food more as a necessity rather than an artform. I think they’re both very important and they’re both part of how I work. They’re two very different approaches but I don’t think I could do what I do without them both.

What do you find most interesting about the intersections of the culinary and fashion worlds?

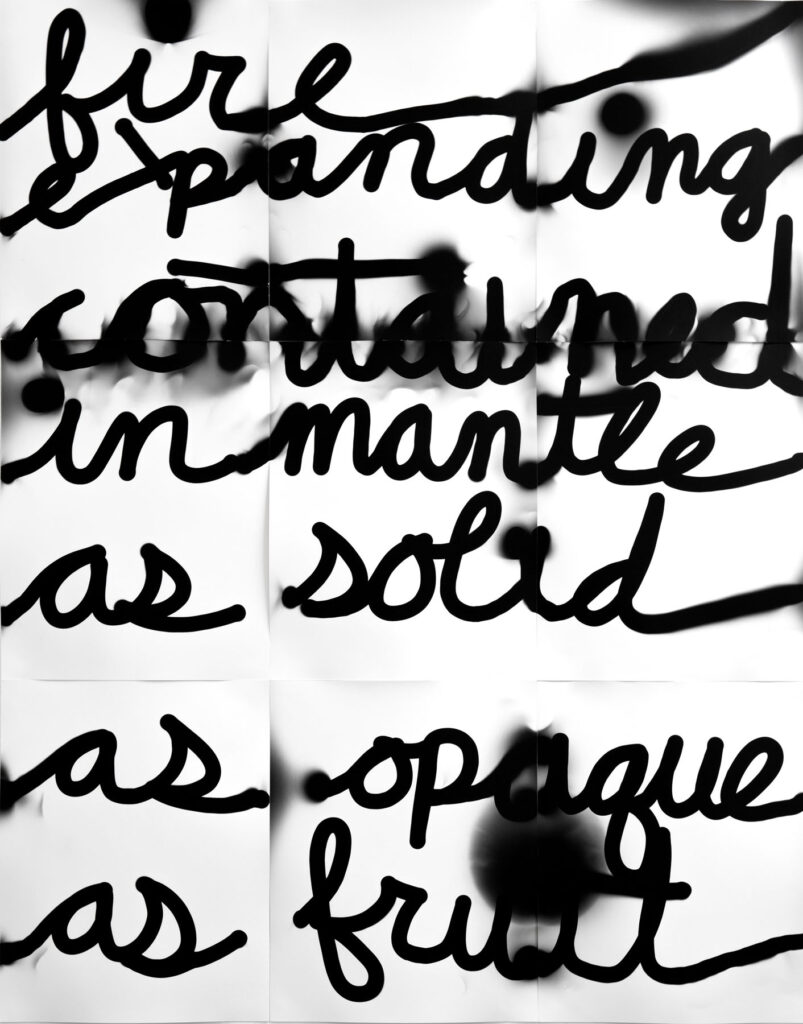

When you work for a food client that wants to sell a product and wants to focus on what that food is for a restaurant or a hotel etc, I think you can get so stuck in trying to sell something, that you forget you can have fun and play around with it. What I really love about shooting food for a fashion brand is that it doesn’t really matter what the food is, as long as the overall image looks good or has an energy or an emotion attached to it that is interesting and visually appealing.

If you were just focussing on food clients, all you really want to do is make something look delicious, and that’s not always the best way of taking an amazing image. Sometimes trying to be too realistic takes away from the magic of creating an image. That’s what I really like doing with brands that aren’t necessarily always about food – you can have more fun with them without having to worry about what every element looks like. As soon as you start to do that you lose the sense of a really interesting image, and it just becomes more about the product.

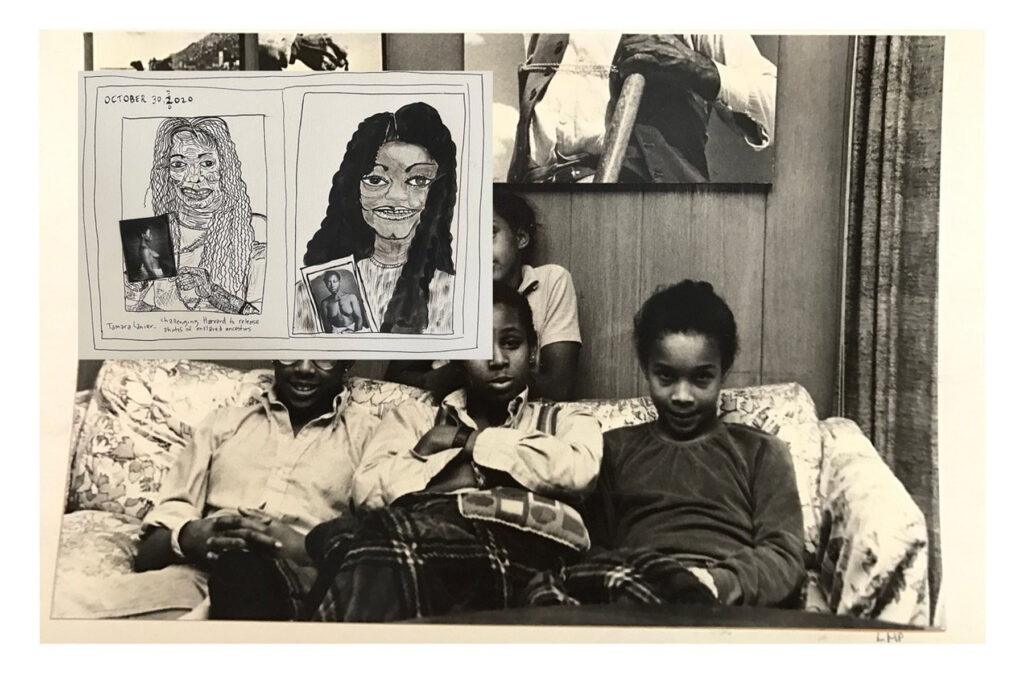

With the theme of this issue being Identity, I thought it would be interesting to hear about your signature dishes or any favourite recipes from your childhood.

Honestly, the thing I love to cook the most is pizza. I know it sounds really basic, but it’s what I love to make the most. It’s so simple and it’s something that everyone loves, but its also something that is a lot more difficult than people think – it took me years to perfect a really good dough.

I also love pastries, and I love to cook with seaweed. I don’t really have a specific recipe that I go back to, but there are certain kinds of food that I seem to always go back to, and then maybe new flavour combinations will come out of that.

I’m really into cooking vegetable skewers at the moment, but things come and go depending on the season. Since I’ve been vegan, I find the versatility of an ingredient like seaweed to be really interesting.

What stands out to you most about the London food scene?

The level of the food industry is really high in London. When I go back to places like France, people always ask me ‘don’t you miss French food and French ingredients?’ and in Italy it’s the same. People say the food is disgusting in London, but I’ve had some of the best food in the world here. There are so many people from all over the world, and so many different communities – you can go east and see the Vietnamese community, you can go a little bit more north and see the Caribbean community, and every community has some stand out places that are incredible.

Something I miss when I go away is that idea that I can have food from all over the world. If you know where you’re going, you can find things that are incredibly special, and I love that.

The downsides are that it’s a very fast-paced city, and a lot of restaurants open and close really quickly, because its very expensive and its not necessarily financially viable to run a restaurant. I think in general, it’s a very hard city to break into. The food industry is one of the most difficult industries to get into. It’s very challenging to own a restaurant and I admire people who can actually run a restaurant 24/7, because it’s so demanding and such hard work. But I think it’s also a very special place for food.

I love it. It’s so diverse, and we have some of the best chefs in the world here. So many chefs come through London just to open a restaurant because they know the clientele is here.

Do you think you would ever live anywhere else?

That’s the question I’m asking myself! I’ve been here for 14 years, and I love it, it’s an exciting city, but I think the older I get, the more I realise I’m ready to live a life that’s a little bit more relaxed.

I think as long as I have a foot in London then that’s fine. I’d still want to be in the city, because it’s an exciting place to be, and I think you learn so much from other people here and get so easily inspired. I don’t think the level of creativity would be the same in a smaller city, and I think I would miss that if I left. But I’m definitely drawn to a more relaxed lifestyle with a bit of sun.

Is sustainability important to you and your work?

Yes, its really important! It wasn’t something I thought was that important when I started working, but now I think every chef in the world has some level of responsibility and should understand that we can’t really be cooking in the same way that we were 50 years ago. I think if we want to move to a more sustainable food chain in general, and we want to really improve our systems, whether that’s the way we farm and fish or the way that we eat – I think it’s a collective effort.

I think chefs have a responsibility to show people options and to make good examples. I take it quite seriously, that’s why I don’t cook with meat and fish anymore. Especially in a big city, you hear lots of people say, ‘what if we all bought meat and fish from sustainable farms?’ and that’s great if you have the money to do that. I don’t disagree with the idea that we should still be eating meat every once in a while, I just don’t think it should be part of our diets in the way that it is now – I think it should be something we do extremely rarely.

The problem is that it’s cheaper to buy a kilo of chicken wings in a supermarket than it is to buy really good quality vegetables. I think that’s where the responsibility for chefs lies, in breaking away from that broken system.

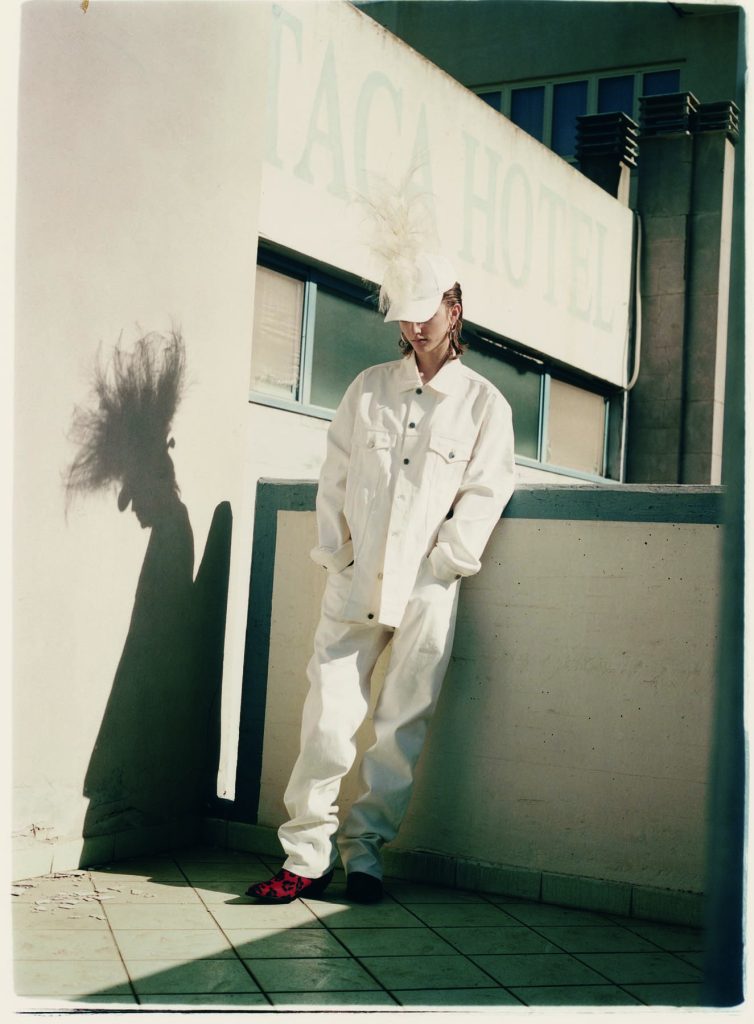

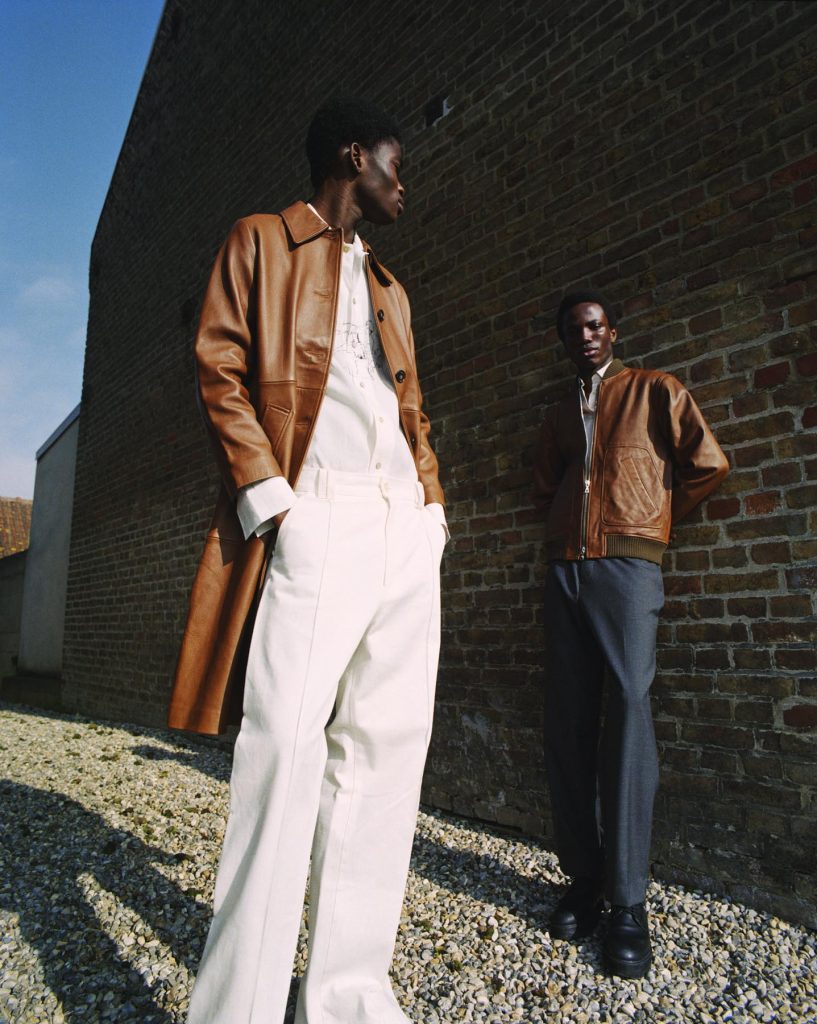

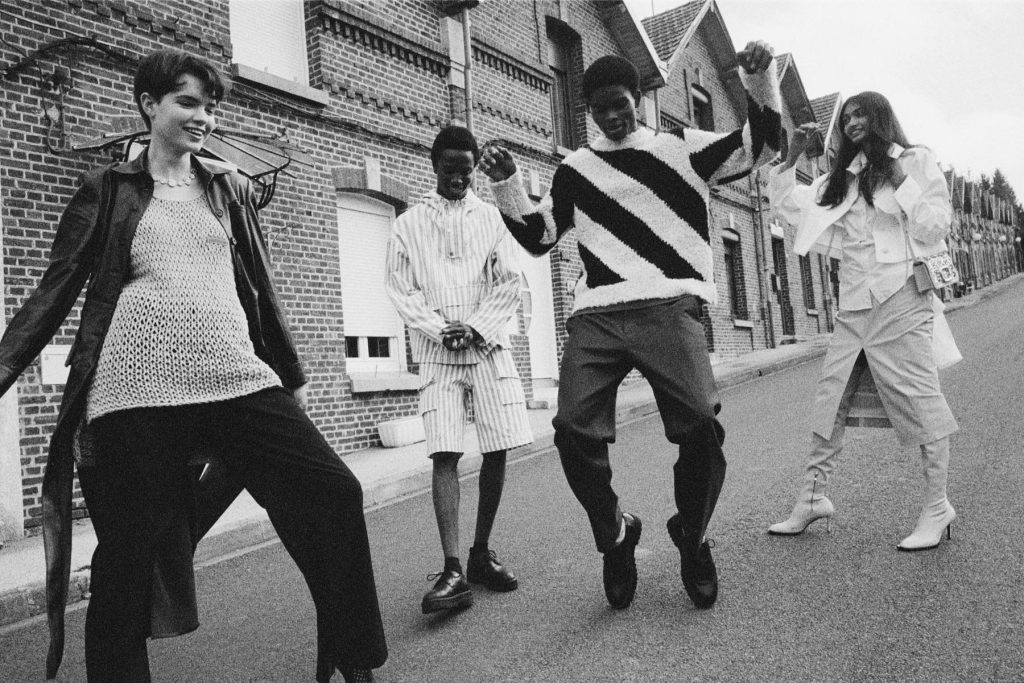

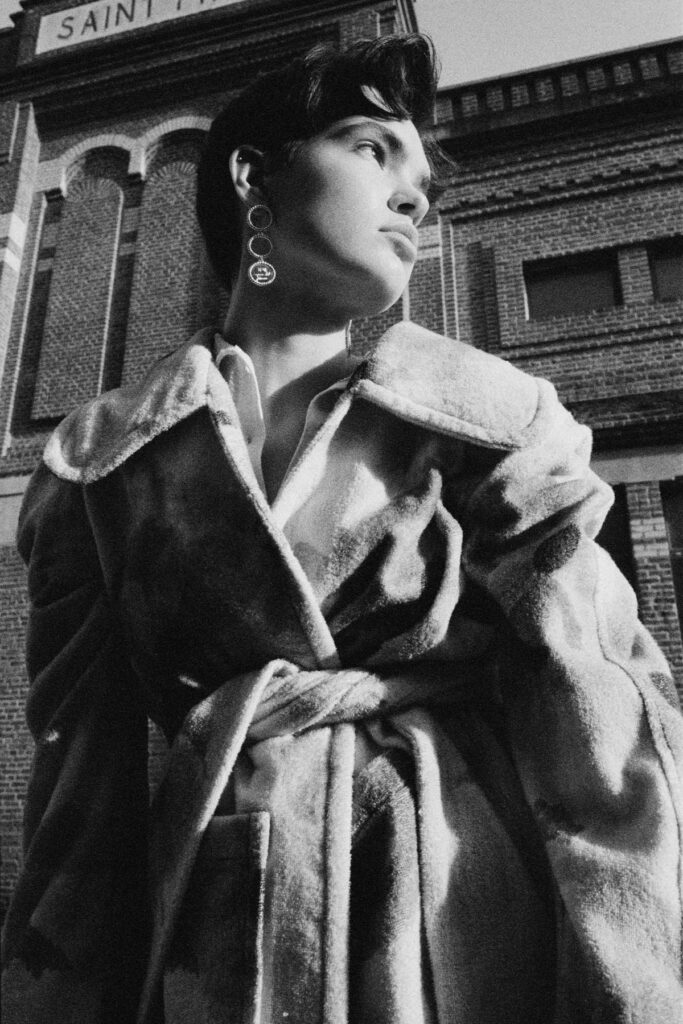

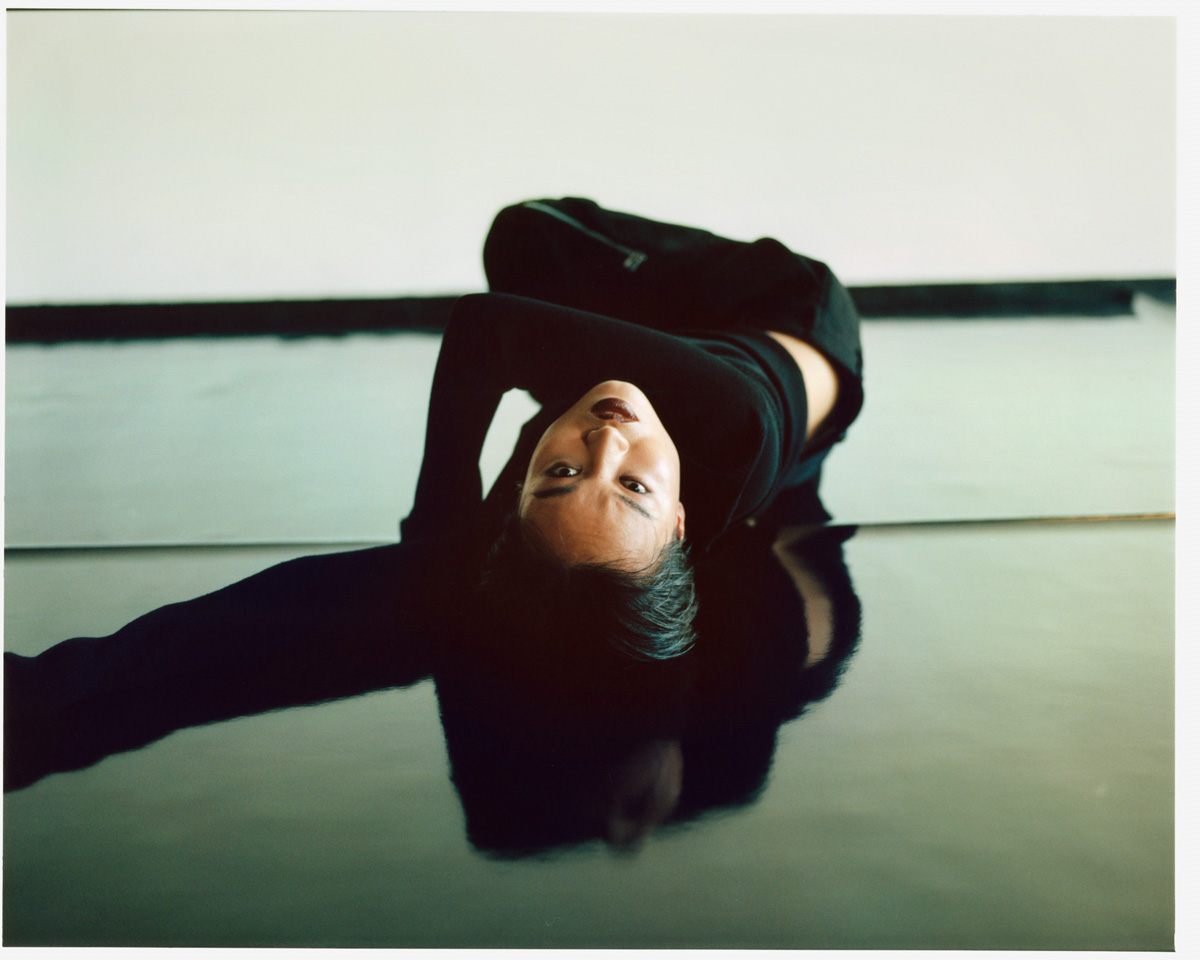

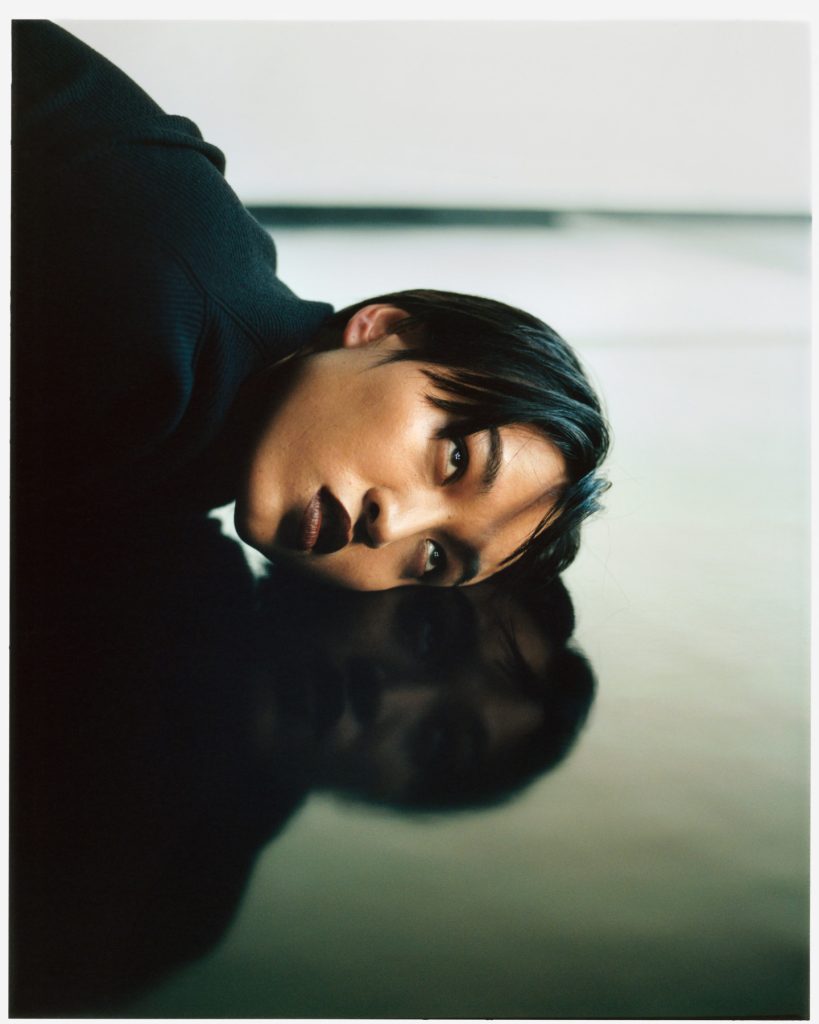

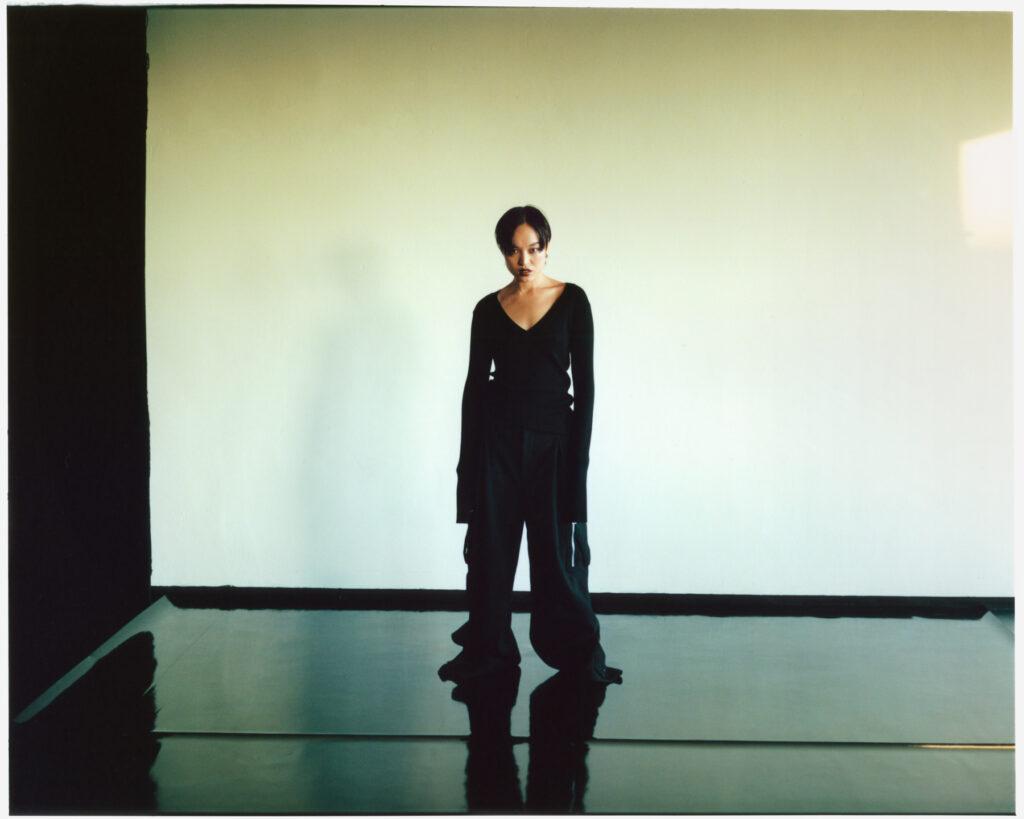

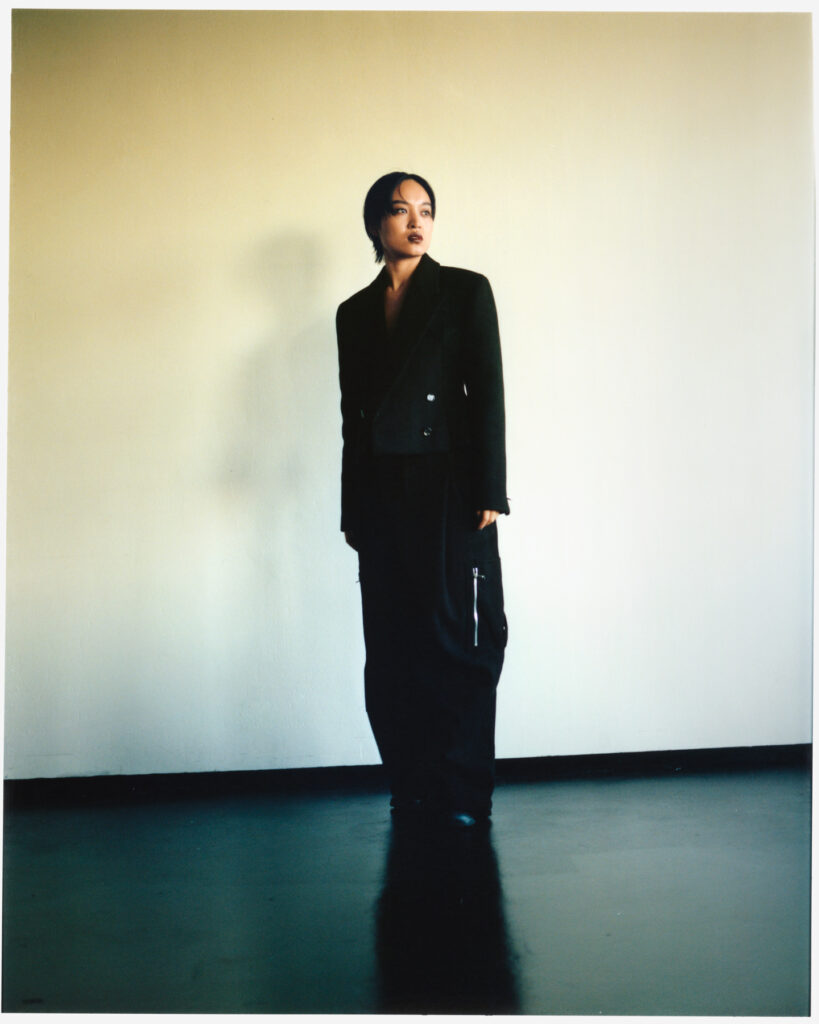

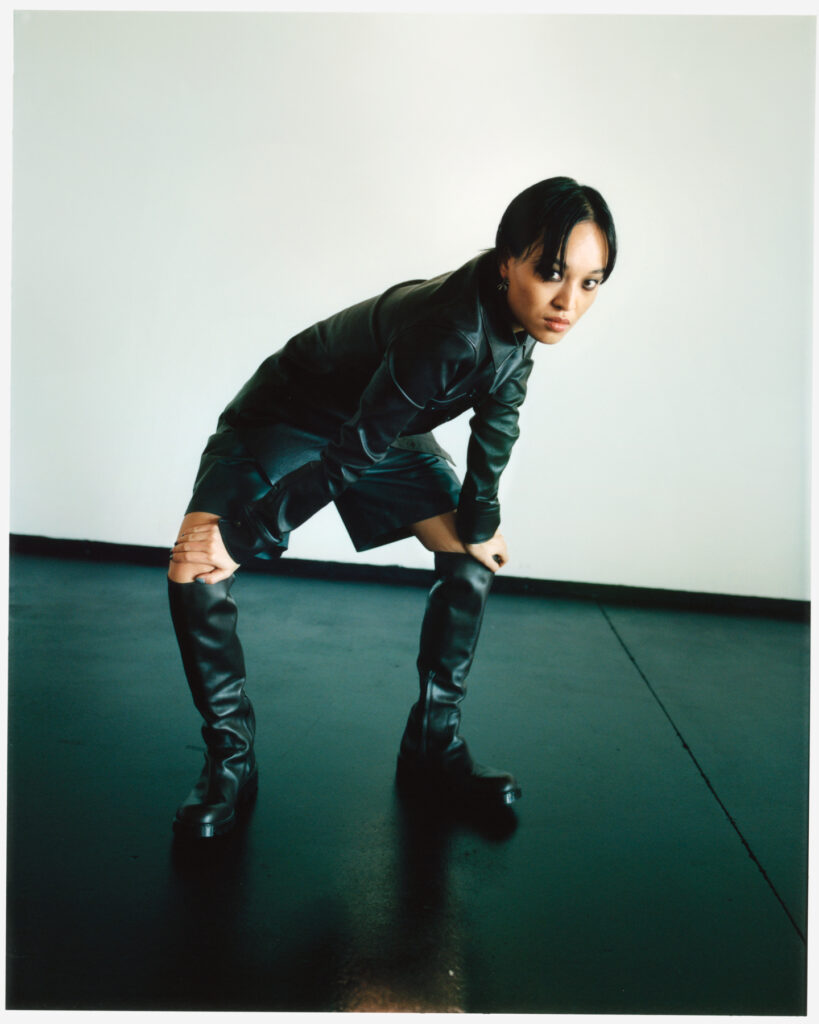

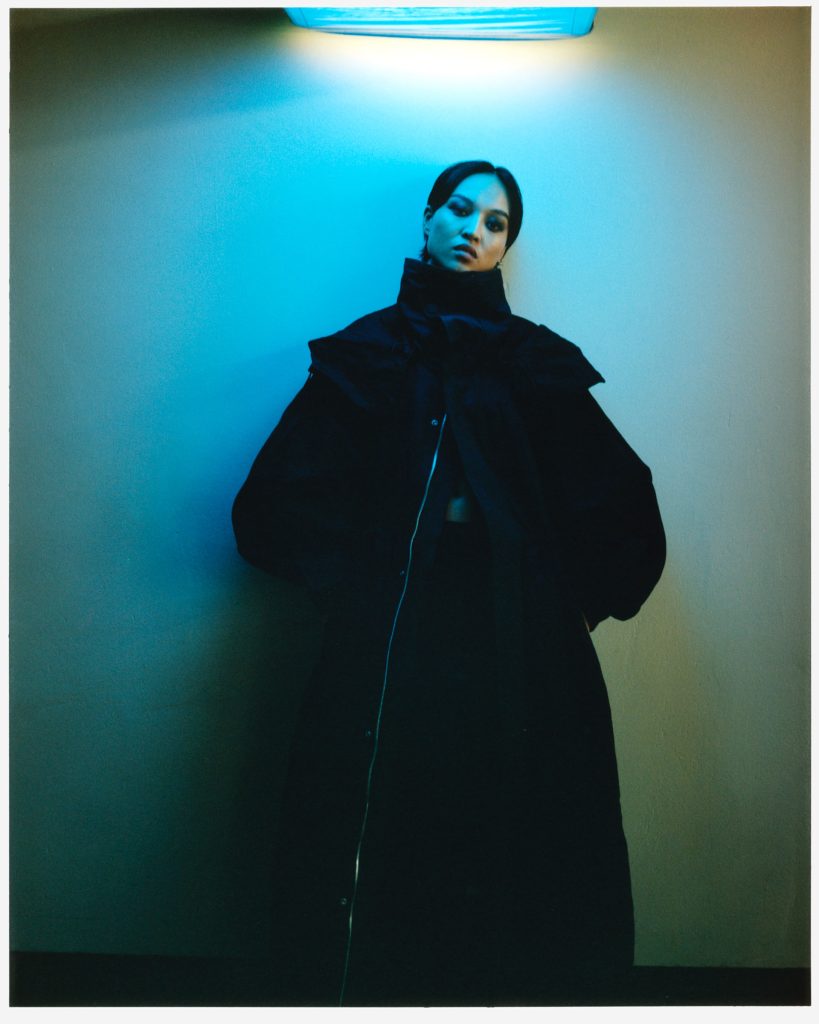

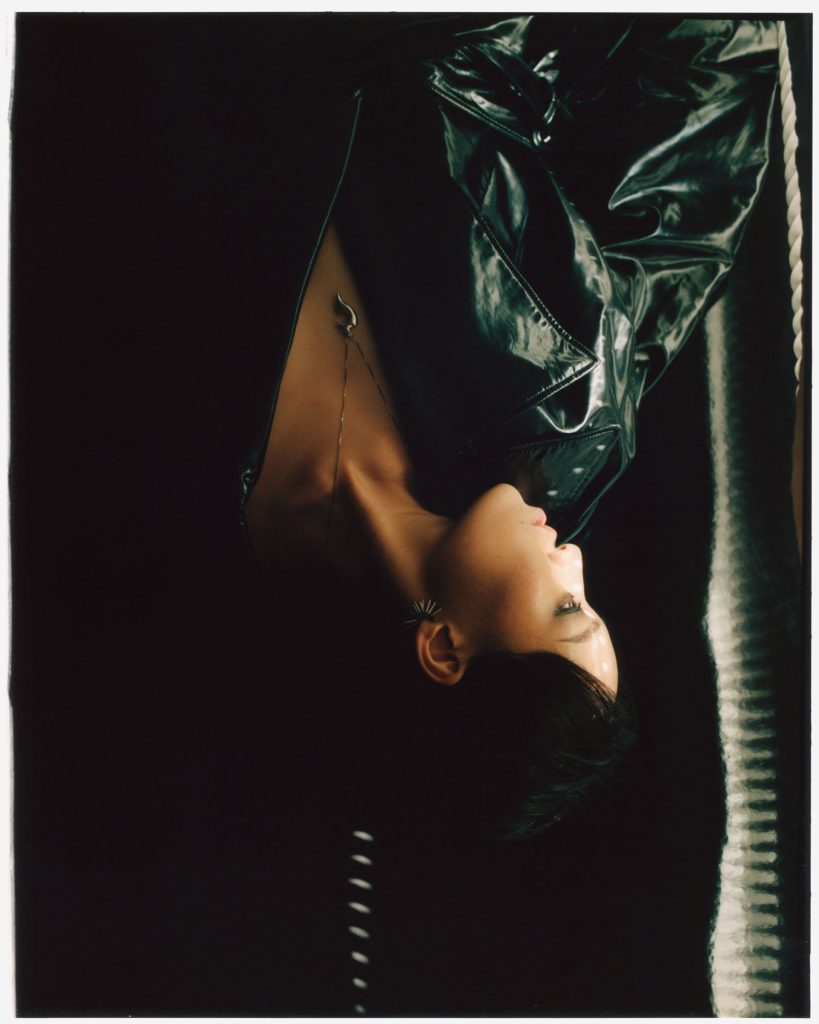

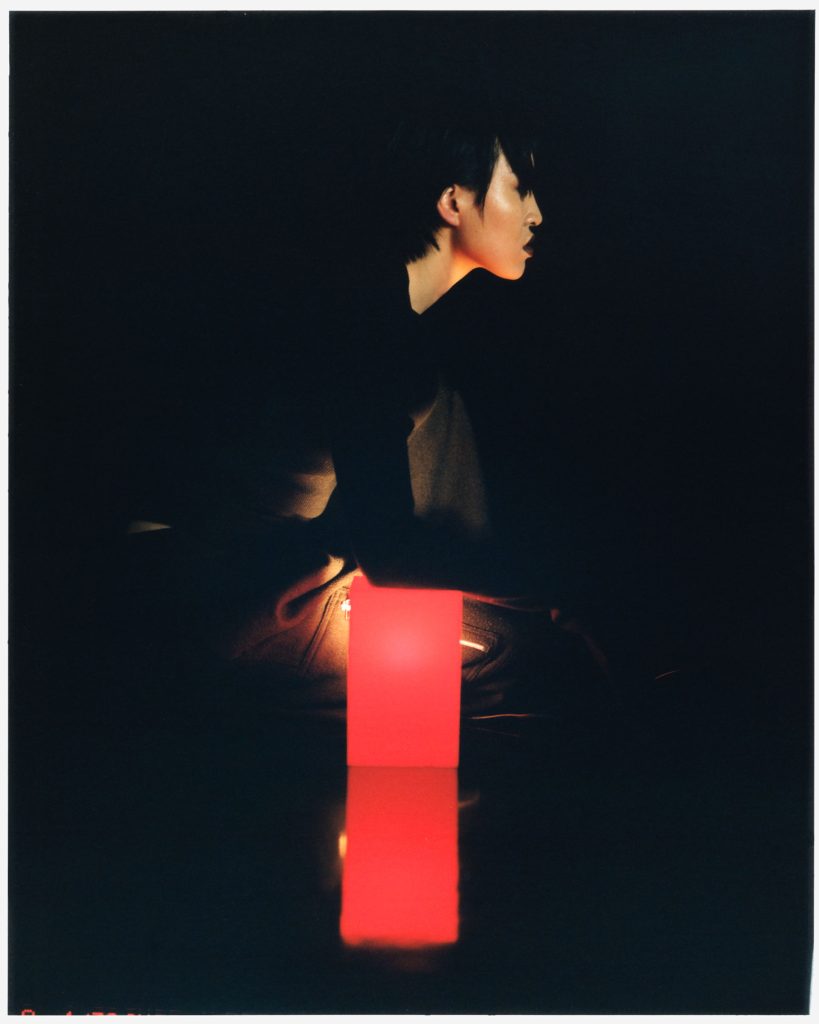

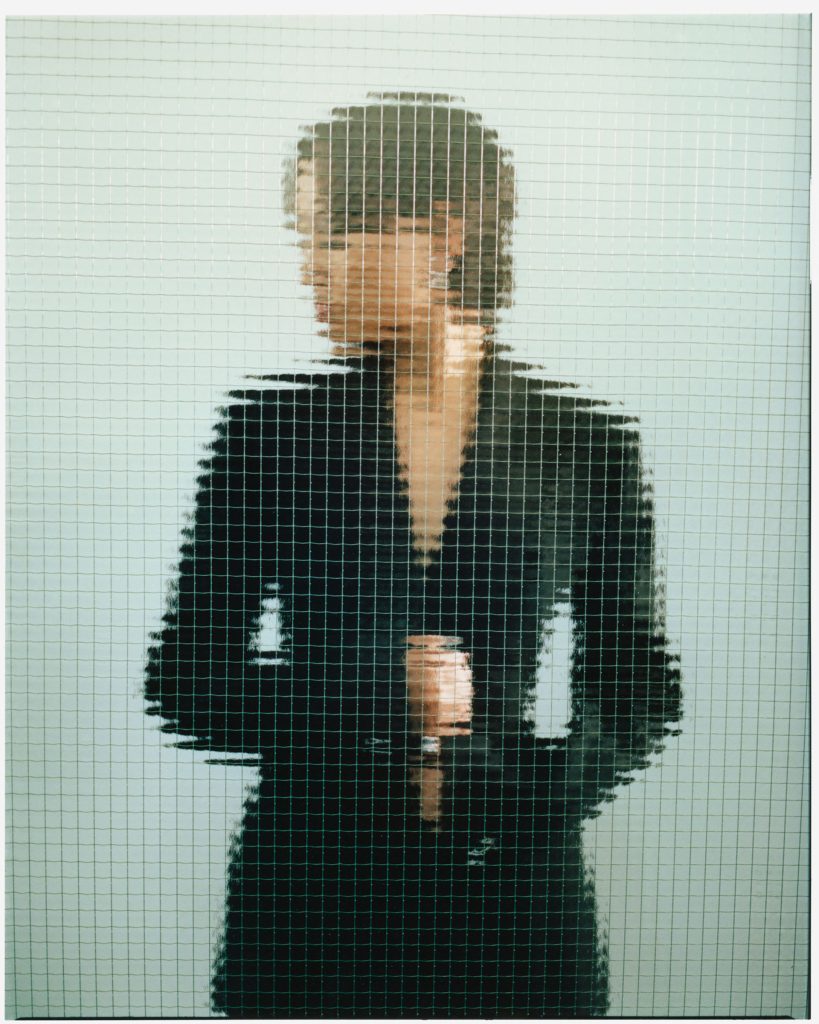

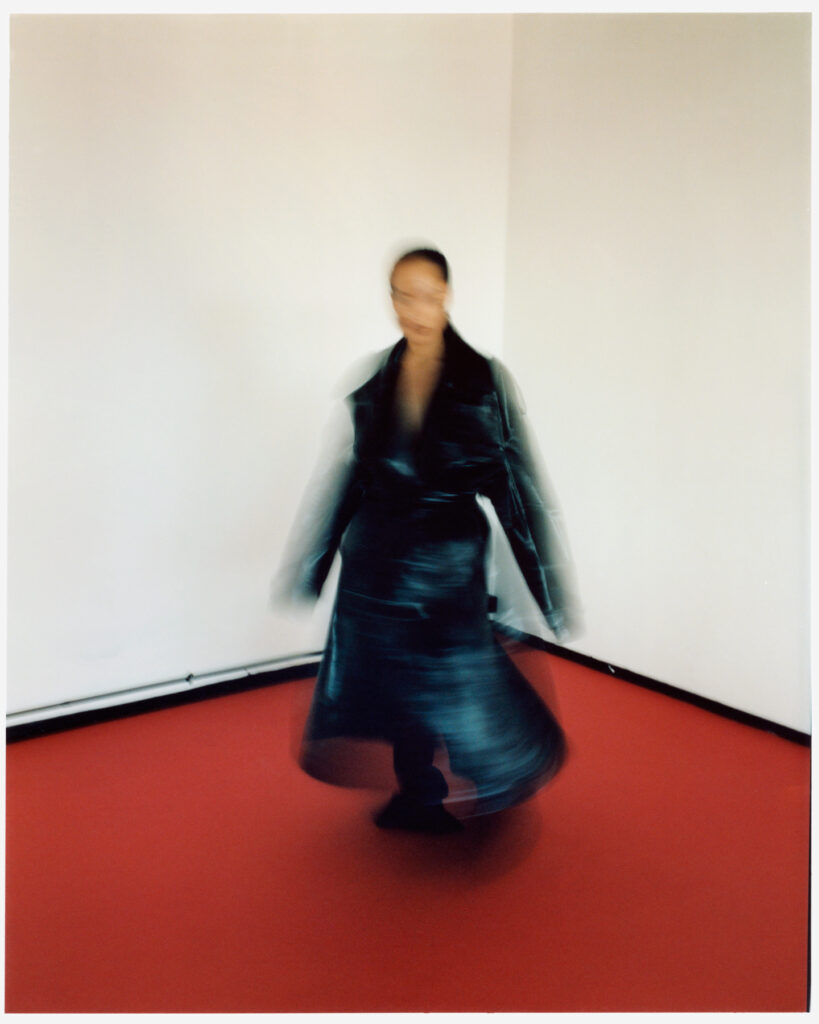

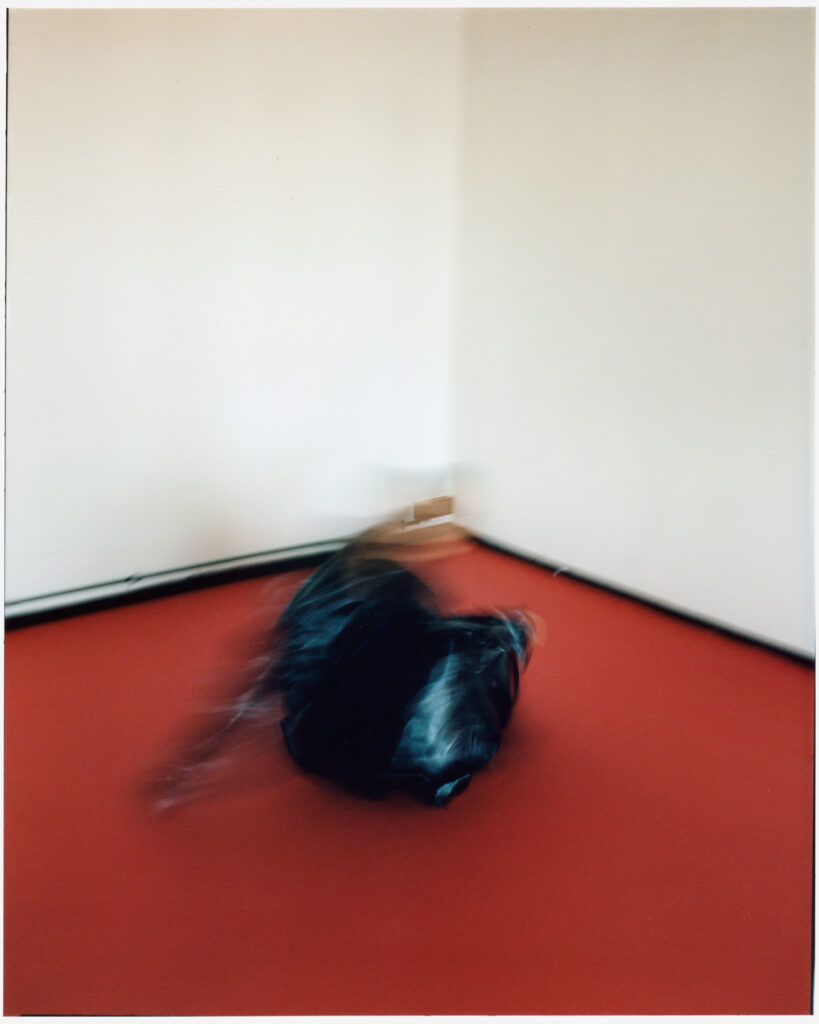

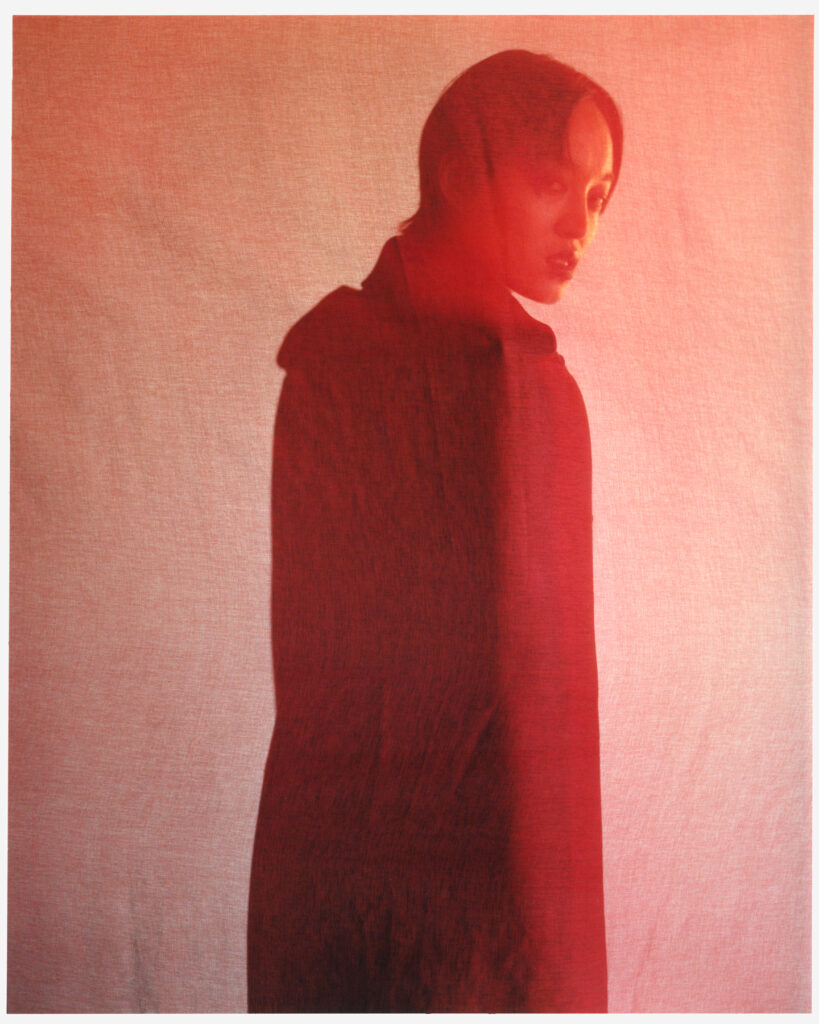

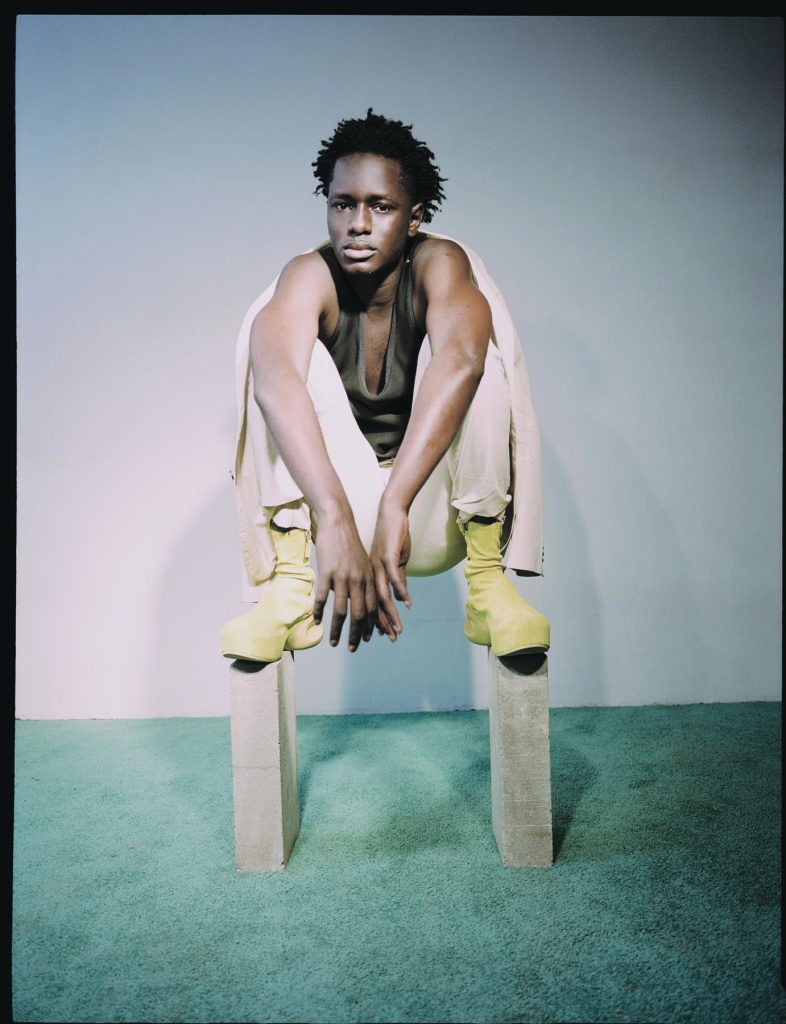

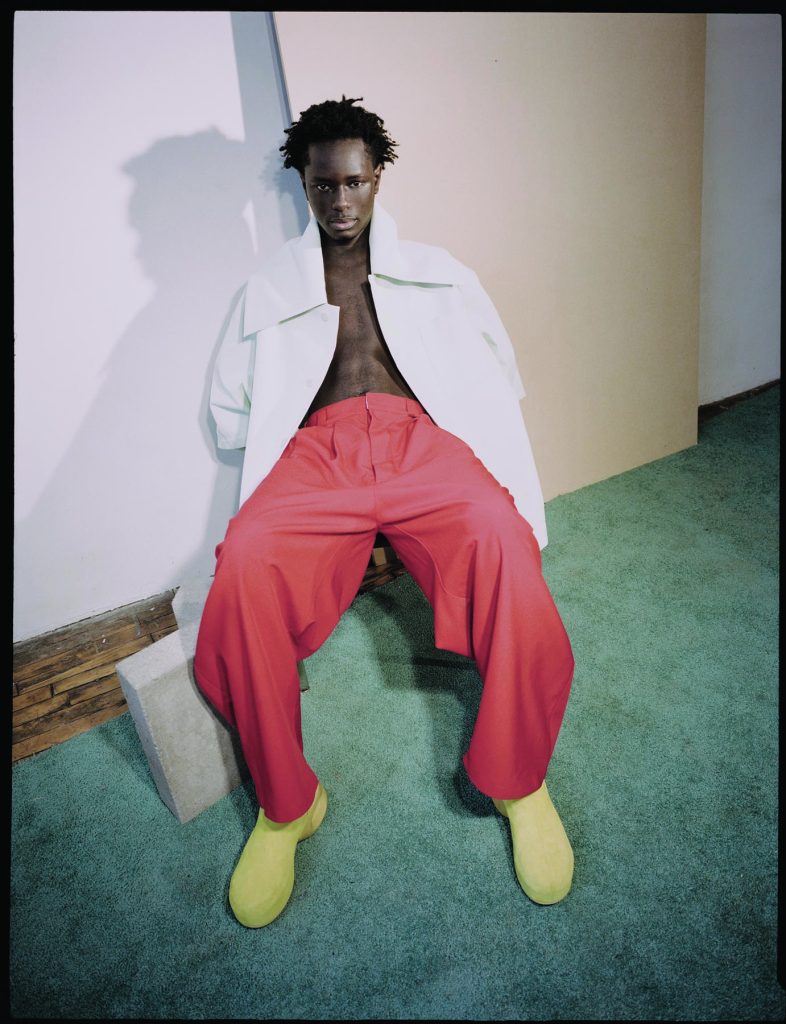

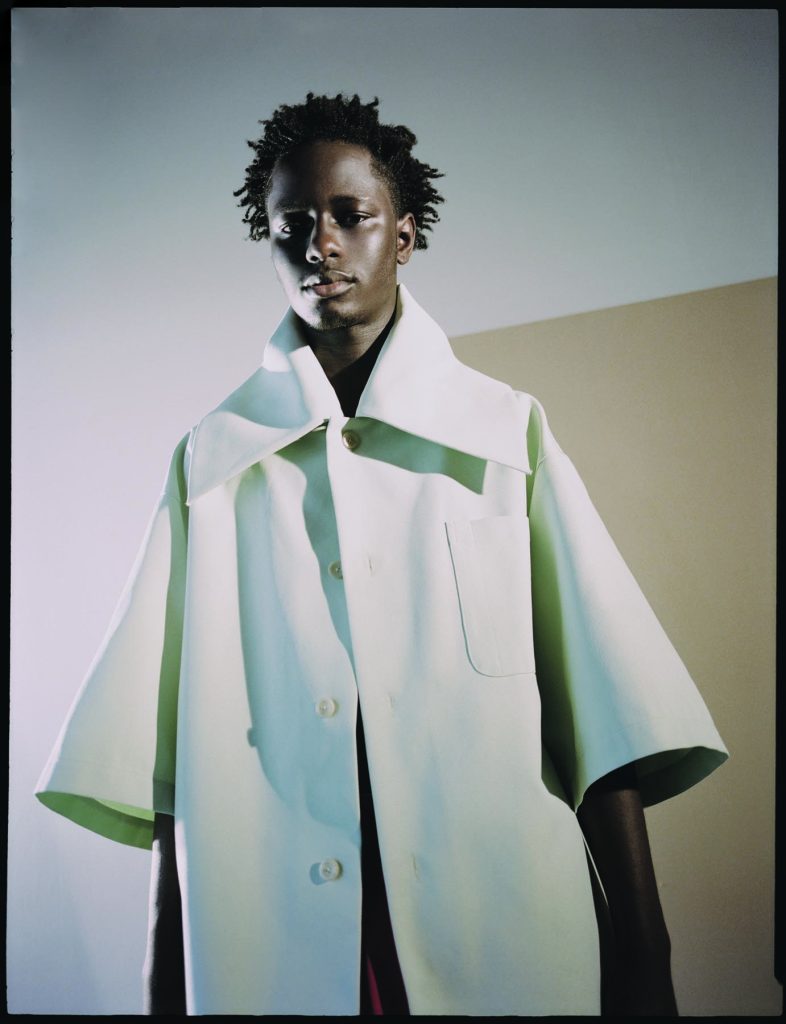

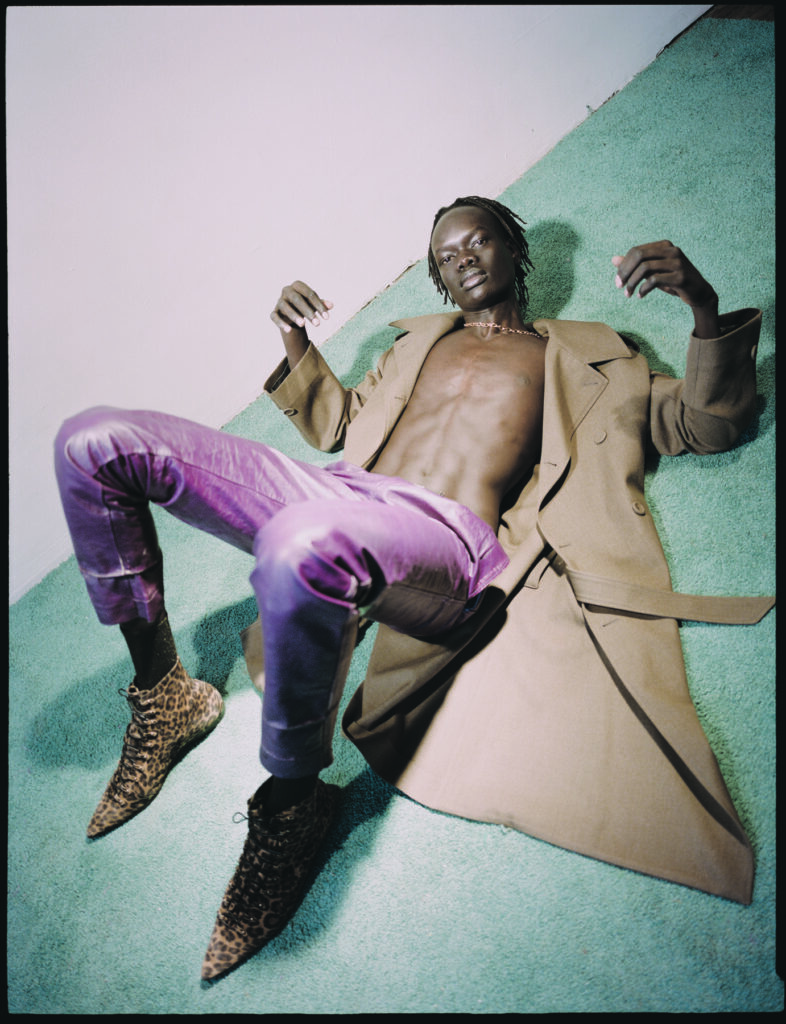

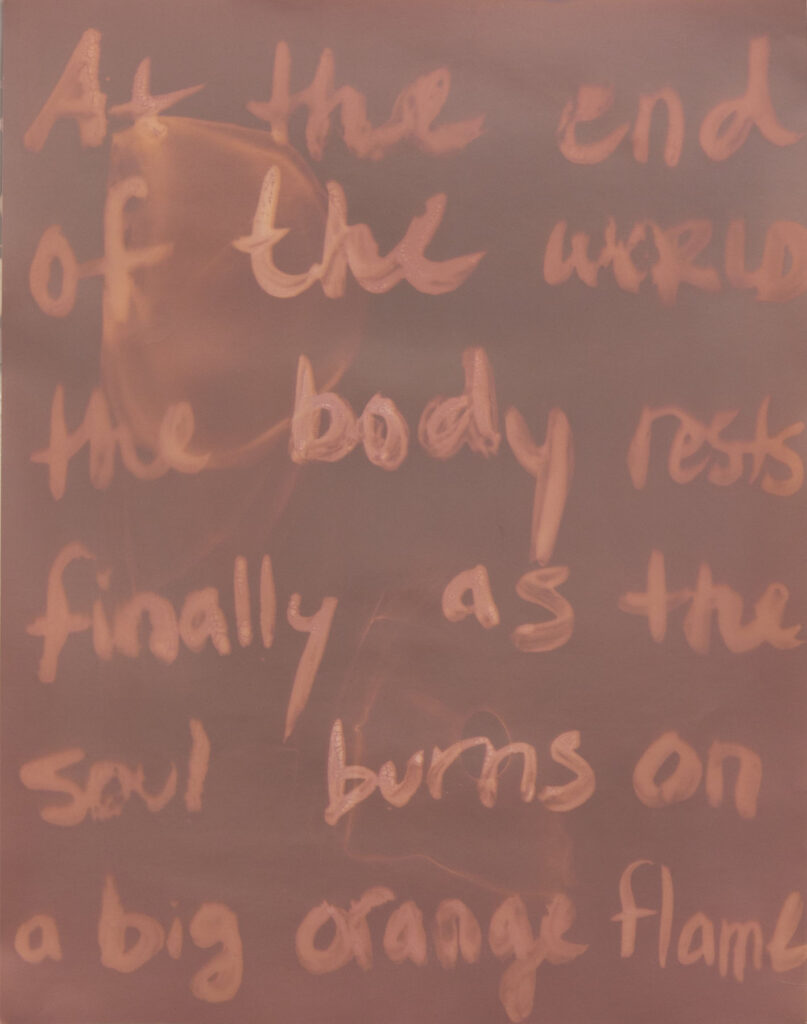

How would you define your visual language?

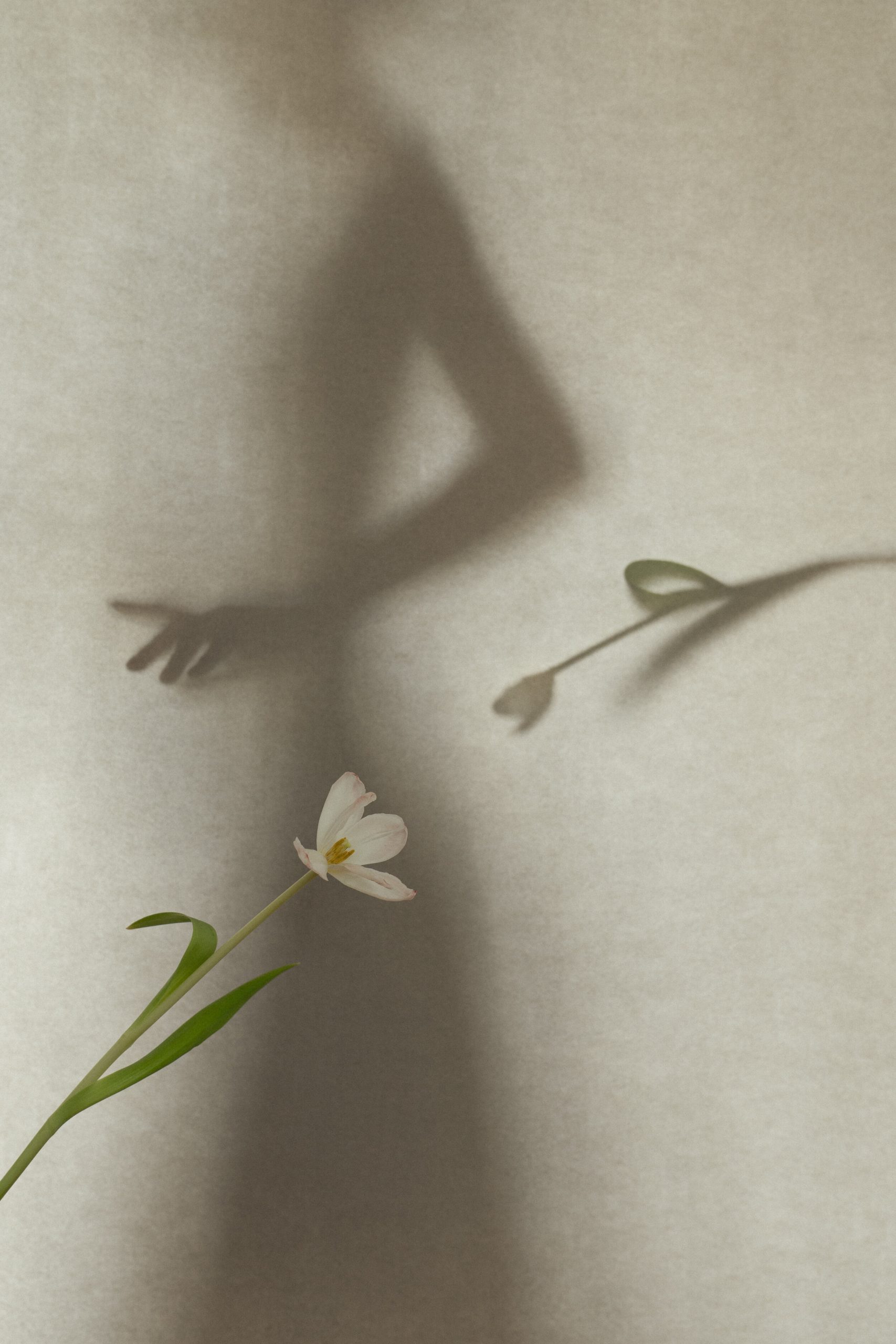

It’s quite dynamic and has a touch of camp to it. There’s something very raw and vibrant to it as well. The idea of photographing things that are very realistic doesn’t appeal to me. I like things that are a bit surreal. That’s what’s fun with photography – being able to replicate something that you don’t always see with your own eyes. I don’t understand the point of photographing things the way that you see them in real life. Why not have fun with it?

There are amazing photographers that do documentary and journalistic work. Some people are very good at that, but for me, it’s more about being able to capture something that is a little bit surreal.

What’s been the most daring or challenging thing you’ve done in your career so far?

I think generally, opening the studio a couple of years ago – that was very challenging. So far, it’s been trying to establish myself as a chef and a photographer on the same level. That was something that before I had the studio, I was really struggling to do, and my career was moving more towards creating imagery and less towards cooking, so being able to establish that has been very important. It has been challenging but also very rewarding, because I realised how important they both are, and how I couldn’t really be doing one without the other.

I think the most challenging things are yet to come. I’m looking at opening a new studio – something a bit more stable and solid, that could be running a more regularly than what I’m doing now. At the moment my studio is here, but I only open it every once in a while for dinners, so I’m looking to open something that could be a bit more permanent.