For the second edition of Sónar Lisboa, a music and visual technology-driven art festival and sister event of Barcelona’s annual happening, which celebrates its 30th anniversary this summer, I had the opportunity to interview Gustavo Pereira, the main curator of the Portuguese team. With years of experience in the music industry and as a well-known DJ and promoter in the city, Gustavo closed the festival with a b2b DJ set alongside the legendary Rui Vargas, delighting the dedicated dancers.

As the festival season opens in Europe, it is fitting that it begins in Lisbon, one of the most beautiful and vibrant cities of Europe, which is also undergoing the most dramatic gentrification on the continent. Festivals have the potential to shape the cultural and social landscape of a city, and in this interview, we explore their responsibility to consider their impact on the local community and create a more inclusive city. Together with Gustavo, we discuss how responsible and inclusive programming of influential cultural organisations and promoter groups can impact the development of cities, gentrification, and support for local artists.

In our conversation with Gustavo, I am curious about Sónar Lisboa’s mission to promote forward-thinking culture, technology, and lifestyle while shaping the authentic side of the Portuguese edition, preserving Lisbon’s diversity and tackling homogenization. We also discuss Sónar’s approach to featuring local talent and its role in supporting the local music industry in the face of gentrification challenges.

As an experienced raver yourself, what changes have you seen in the Portuguese scene in recent years? And what inspirations and influences from the other scenes and cultural spaces have become more prominent here?

I’ve been going to parties and live shows ever since I was really young. First, I went to live shows with my parents, then around 13/14 years old, with my brother, and later on my own. When I started clubbing, I mostly went to clubs and raves around Portugal and Galicia in Spain. I’ve seen lots of live shows, clubs, and nightlife in different genres and settings. Nowadays, I feel we’re going through an identity crisis because of the massive amount of music available today. People get used to that and look for all kinds of music and events, which, of course, is not a bad thing. In a way, it was easier to identify who listened to what, and that’s not happening anymore.

Portugal is a melting pot for diversity and influences from other countries and cultures, and that reflects in the number of amazing artists we have nowadays producing incredible and extraordinary music from what’s been heard before. There is also a lot of respect for the origins and the music foundations. Personally, I try to get a nice balance between the old school and the new school: experience and creativity.

What direction and guidelines in the curation do you share with Sónar Barcelona? And what makes Sónar Lisboa unique and worth travelling to?

We work together on the line-up, but it’s always very important to present a balanced line-up with local talent, live shows, advanced music, and a contemporary vision with a touch of the foundations. Just the fact Sónar Lisboa is happening in a different city makes it unique and gives it a different touch. The local talent flavour, the gastronomy, the venues, and the experience are different here. Barcelona is the sanctuary, of course, and you can’t compare both. Just assume our differences and make it also special.

Lisbon is going through heavy gentrification, people are being pushed outside of the city, and young local creatives can hardly afford to live in the city, which is, of course, a significant loss for the city’s cultural development. Is there a way for Lisbon’sLisbon’s music industry to have a say in this development and think together with the city about how to make this situation fairer for the locals (I noticed the festival had been supported by Turismo de Portugal, Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, and Turismo de Lisboa, so I assumed such conversation might be a part of the discussion within your team)?

There’s no interference in the work of those institutions from Sónar Lisboa. We have main concerns, and of course, we try to fight to promote the local culture and give everyone some voice and promotion as much as possible. It’s not an easy task, but the support from these institutions is also essential for our job here and shows their interest in it. At the moment, only the Lisboa city hall is supporting us, and we really appreciate it, but of course, the initial support from the other institutions was really important for our kick-off.

Due to its long history of immigration and colonisation, Lisbon is home to a diverse and vibrant mix of cultures, contributing to the city’s unique cultural identity. The city has been a port of entry for people from many parts of the world, including Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Gentrification can lead to a homogenization of the city’s culture, making it difficult for underground creatives to find audiences and venues for their works. How can Sónar, as an establishment for a forward-thinking culture, technology, and lifestyle, contribute to preserving the city’s diversity and tackle the problem of homogenization?

Sónar Lisboa is part of the private cultural sector that helps promote and disseminate multicultural and diverse artistic talent. We have in our backbone the will and passion for exploring the heterogenization of national and international culture as much as possible, especially in the music and visual sector.

The Portuguese artists featured on this year’s Sónar line-up, such as DJ Nigga Fox, Rui Vargas and Gusta-vo, Violet and Photonz, and Sensible Soccers are significant to the local club scene and also made an essential impact on putting Portugal on the global map, and thus, of course, are essential to be a part of your booking. Yet, from some recent conversations with friends from the underground music scene in Lisbon, I learned that the smaller collectives feel underrepresented by the big festivals in Portugal, such as Sónar, that could potentially offer them financial support and opportunities to build international audiences and gain recognition. How do you, with your curatorial team, approach featuring the local talent in your program?

We try to balance our work and actions as an organisation as well as possible. Of course, some of the names are already recognised but new and fresh names from smaller collectives as well. We keep our ears and eyes open but unfortunately don’t know all of them as we wish, and also, we don’t have slots for everyone all at once. We try not to repeat many artists from one year to another to give space to different artists to be part of Sónar Lisboa.

One of the central features of this year’s program of Sónar is the AI-generated image campaign. The fast-growing advances and use of AI technology have caused considerable anxiety in creative communities. There’s a growing sense of the digital and physical becoming blurred and reality becoming increasingly subjective. What role does the discussion on the AI influence in the music and visual art production play within your team and the scene you represent?

The discussion makes the intangible more tangible, and the conversation allows an ongoing dialogue within a community that can help regulate, find solutions, and even integrate responses to problems from our everyday life.

Sónar focuses not only on music but “Music, Creativity and Technology.” In your view, what trends and developments are driving the evolution of electronic music?

Definitely machine learning is interacting with all forms of music and visual development in this industry. A lot is being done with new ways of processing these two separately and in an integrated way.

There’s been a growing competition among fast-emerging artists, many of whom are becoming popular over social media. Social media is also a result of technological advancement, but it often exploits its consumerist side more than its unlimited possibilities for creativity. Sometimes the artists who mostly invest time in developing their production and DJing skills find it hard to keep up with the artists who are more affine to social media and know how to keep their audiences entertained on Instagram or TikTok. Considering these developments, how can creativity be encouraged and nurtured more evenly in the electronic music industry today?

Social media occurs on and by the use of platforms, and they can allow us to show creativity to an amplified audience. You can see that on the best brands and pages you follow, so we should condemn the vehicle but the way we use it or not to showcase our creativity and talent. Of course, there’s social interaction at a bigger scale, but I believe that we can input social media with our best craftsmanship and use it in a good way. In a non-paid setting, it’s a recreational space for the electronic music scene.

How do you see Sónar Lisboa grow in the next few years? Are there any specific themes or new formats you want to explore, such as networking events, workshops, discussions, etc.?

I believe Sónar Lisboa’s growth and evolution will be dependent on the core of its context, and by that, I mean the team that makes it happen, Lisboa’s own evolution and growth, and the way the industry evolves we will mirror our own perception of this reality and try to keep things interesting for our audience.

Credits

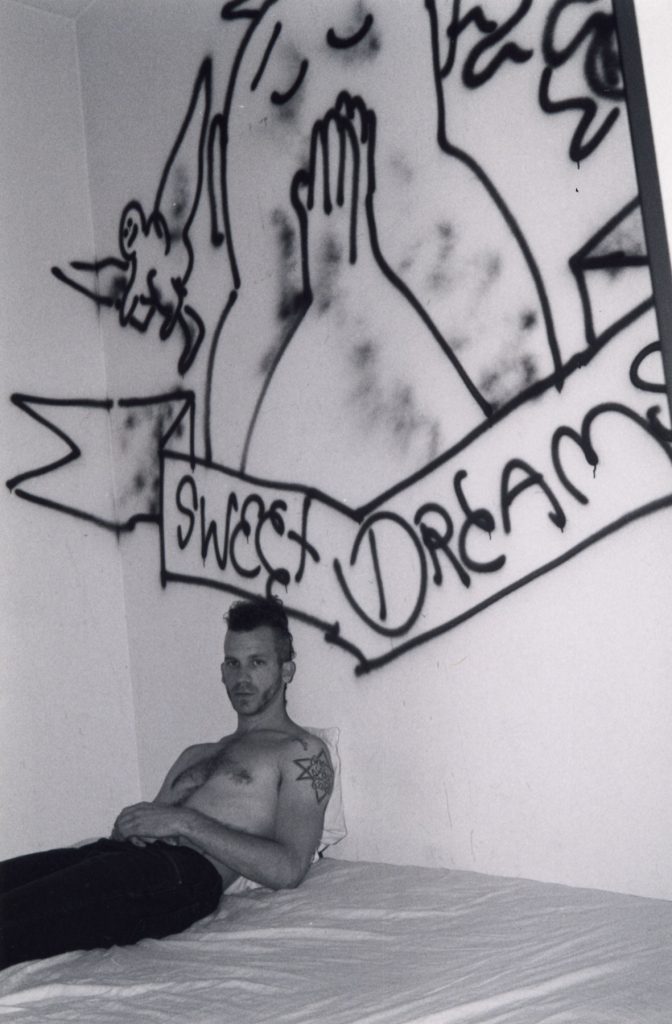

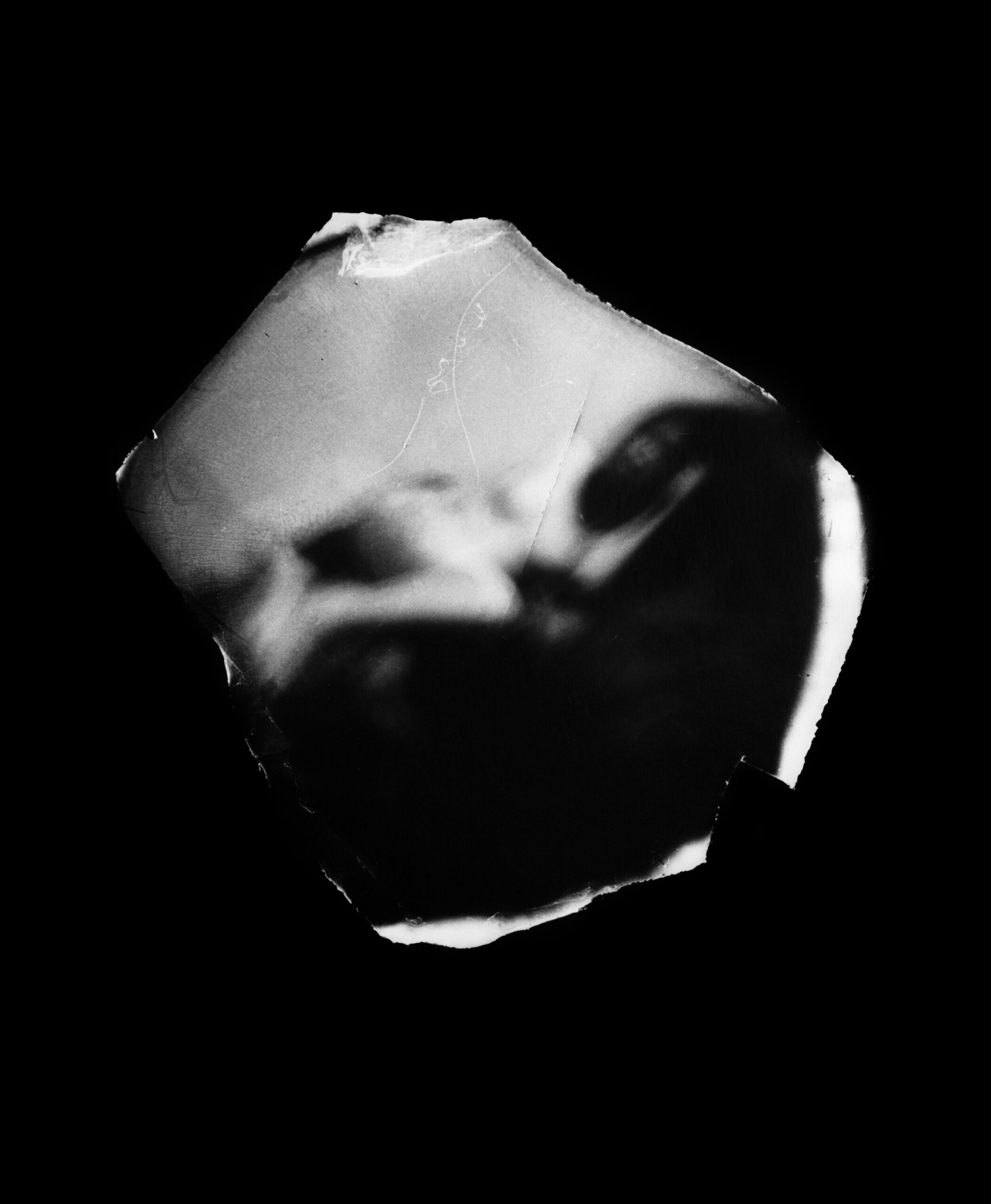

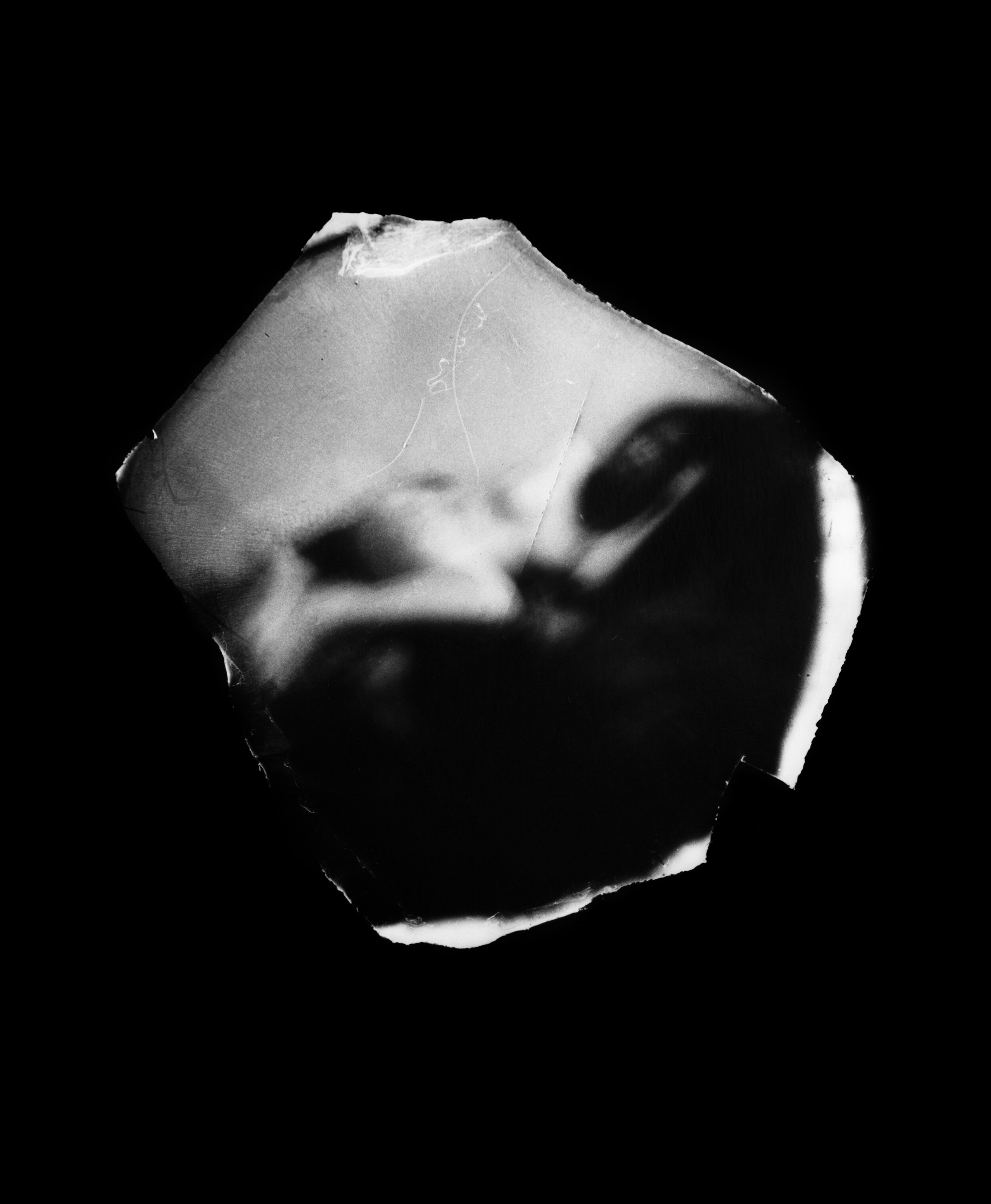

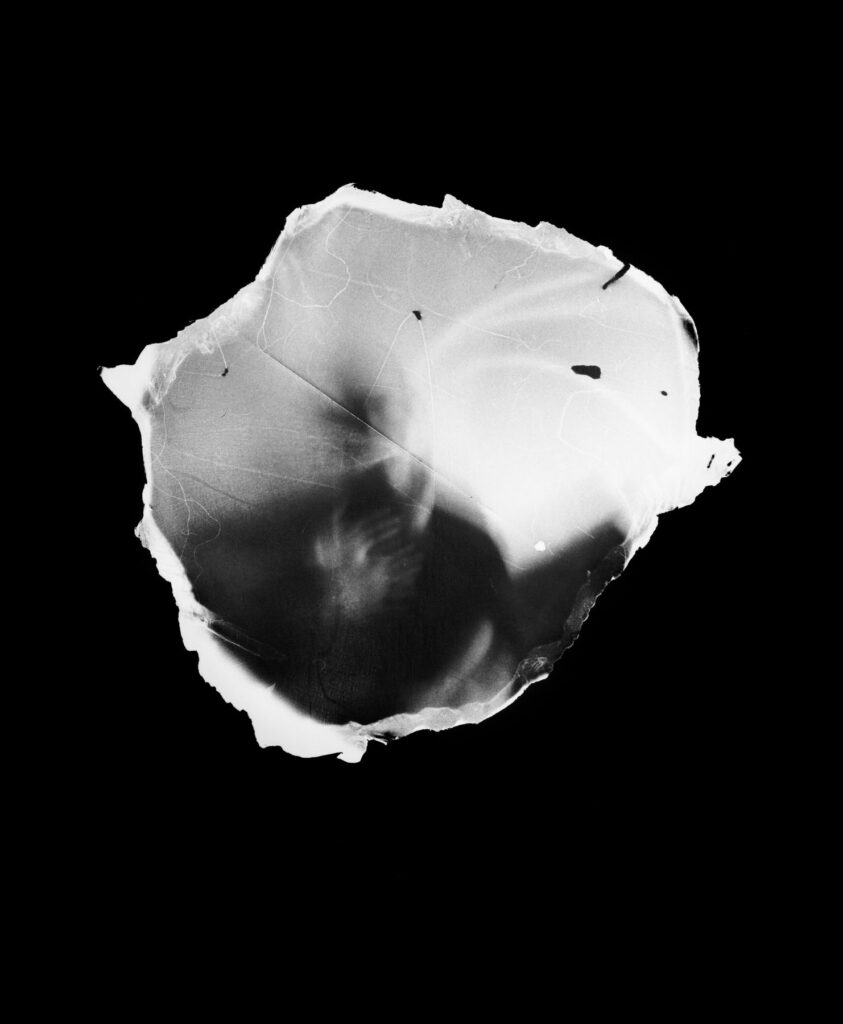

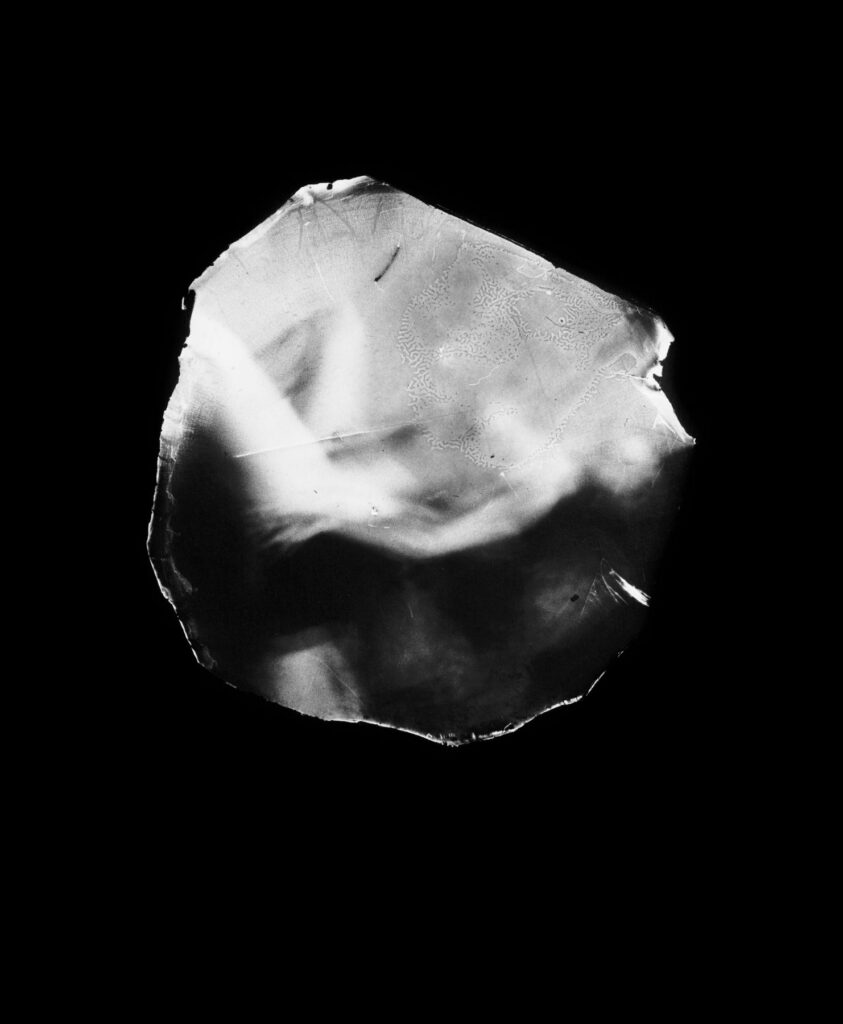

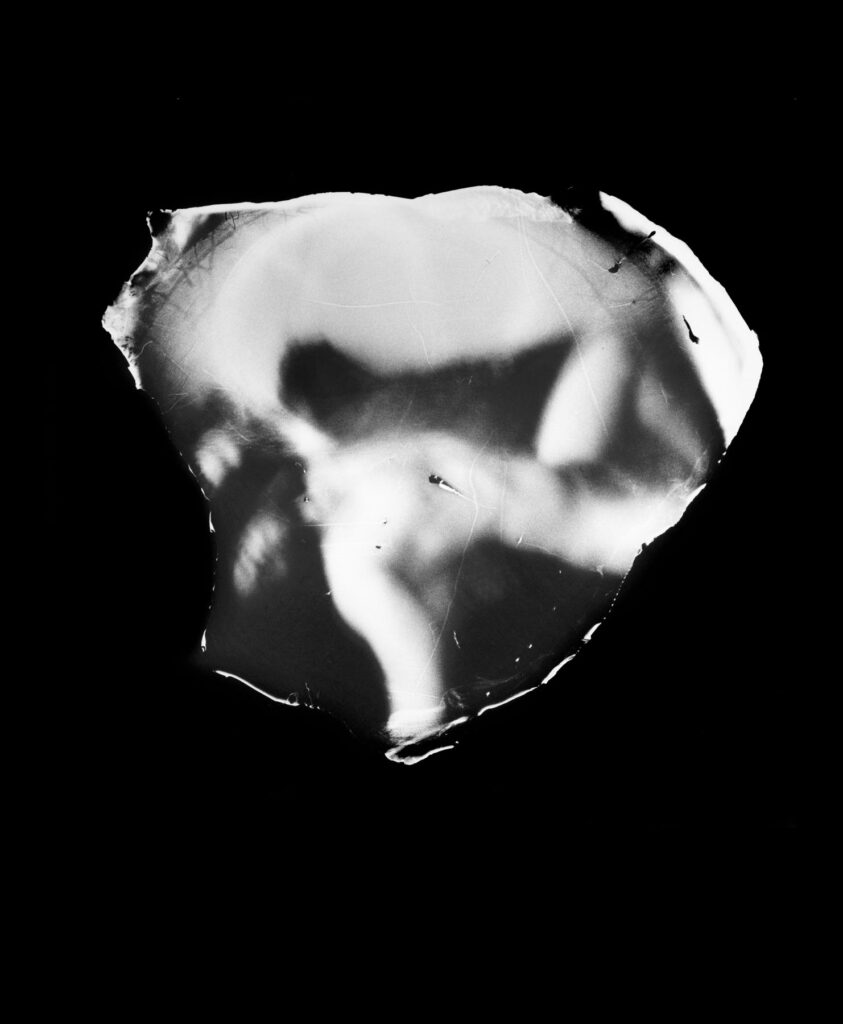

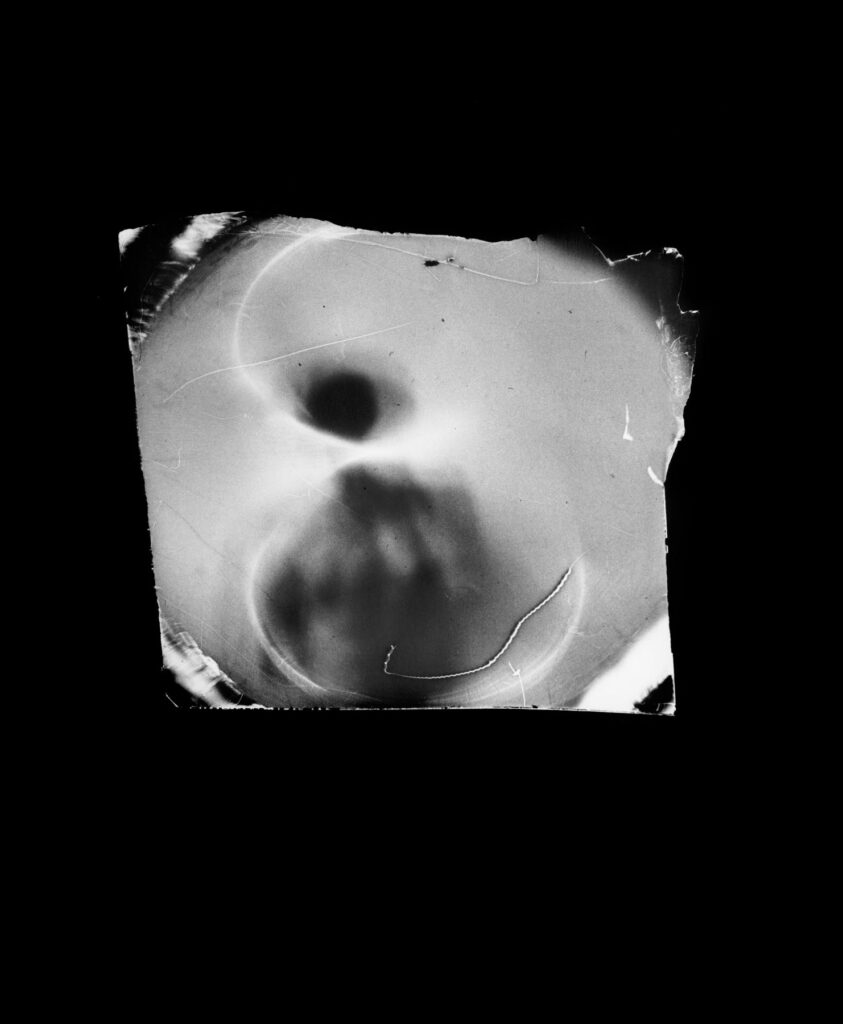

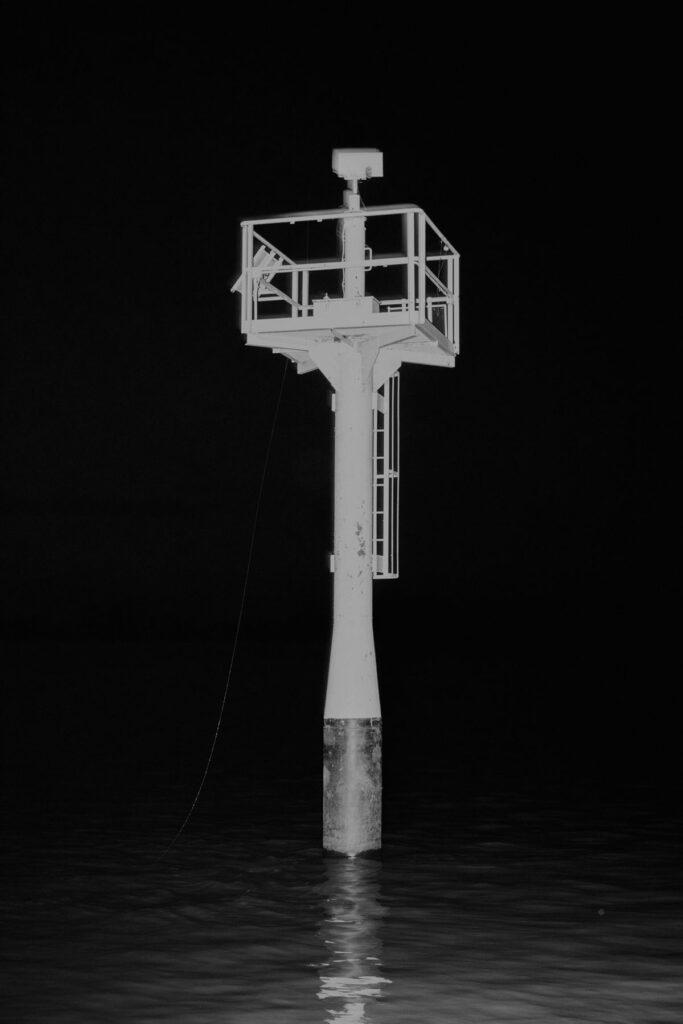

- Luisa, Sonar Park, Lisboa 2023. Courtesy of Pedro Francisco

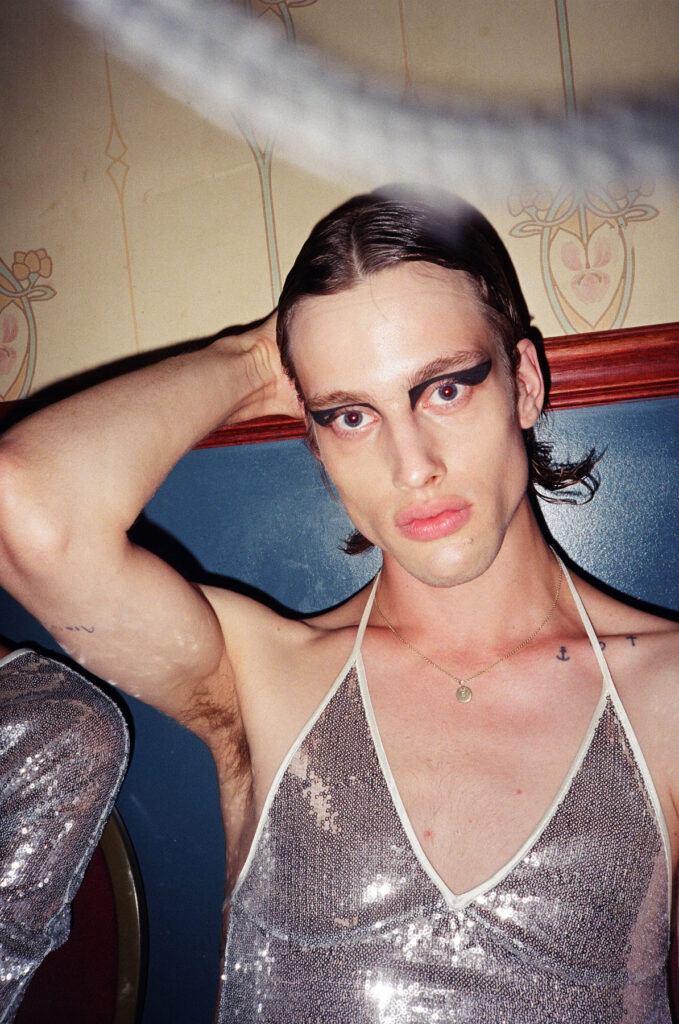

- I hate Models, Sonar Club, Lisboa 2023. Courtesy of Pedro Francisco

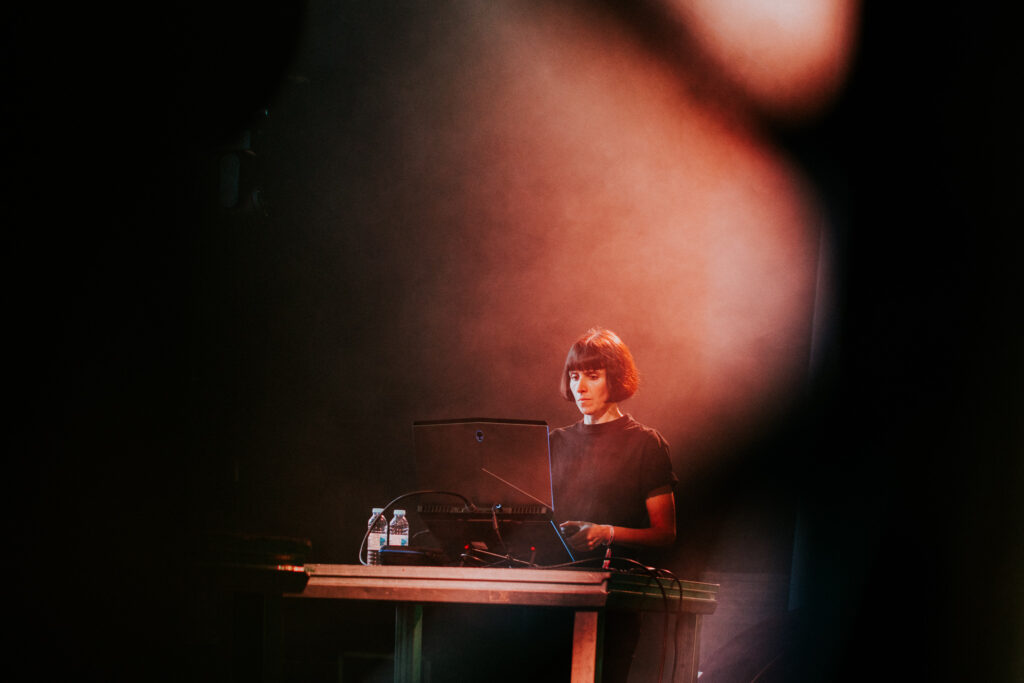

- Sofia Kourtesis, Sonar Club, Lisboa 2023. Courtesy of Pedro Francisco

- Conference, Plaça de Barcelona, 2023. Courtesy of Neia

- Entangled Others, Clothilde, Sonar + D, Lisboa 2023. Courtesy of Pedro Francisco

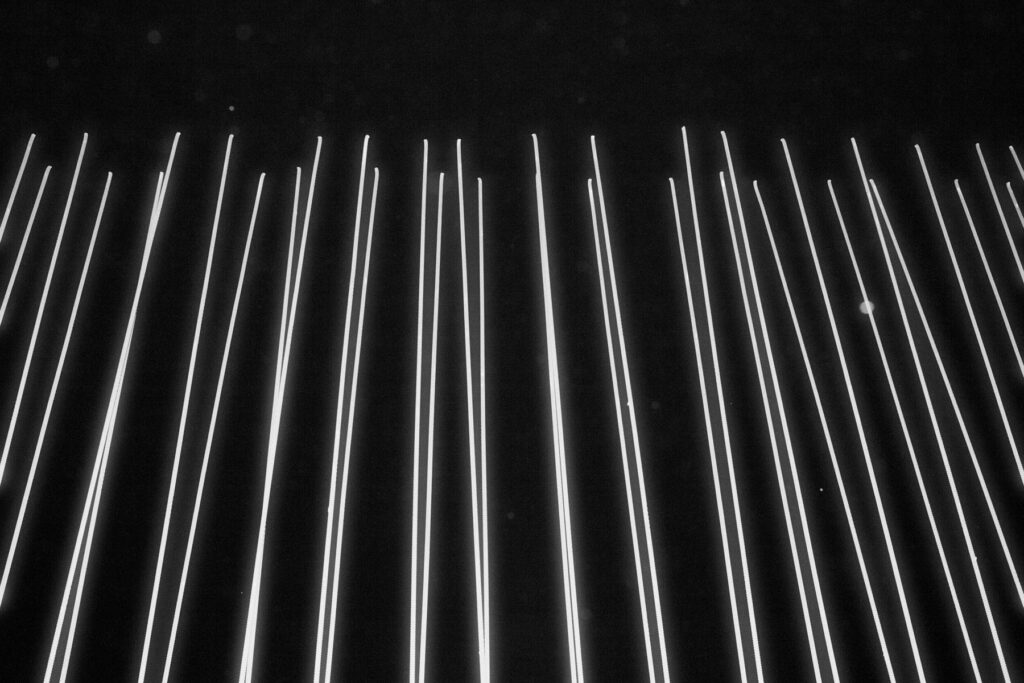

- MetaAV, Sonar + D, Lisboa 2023. Courtesy of Pedro Francisco

- Peggy Gou, Sonar Club 2023. Courtesy of Neia

For more information visit Sónar Lisboa

Special thanks to Rosalie De Meyer