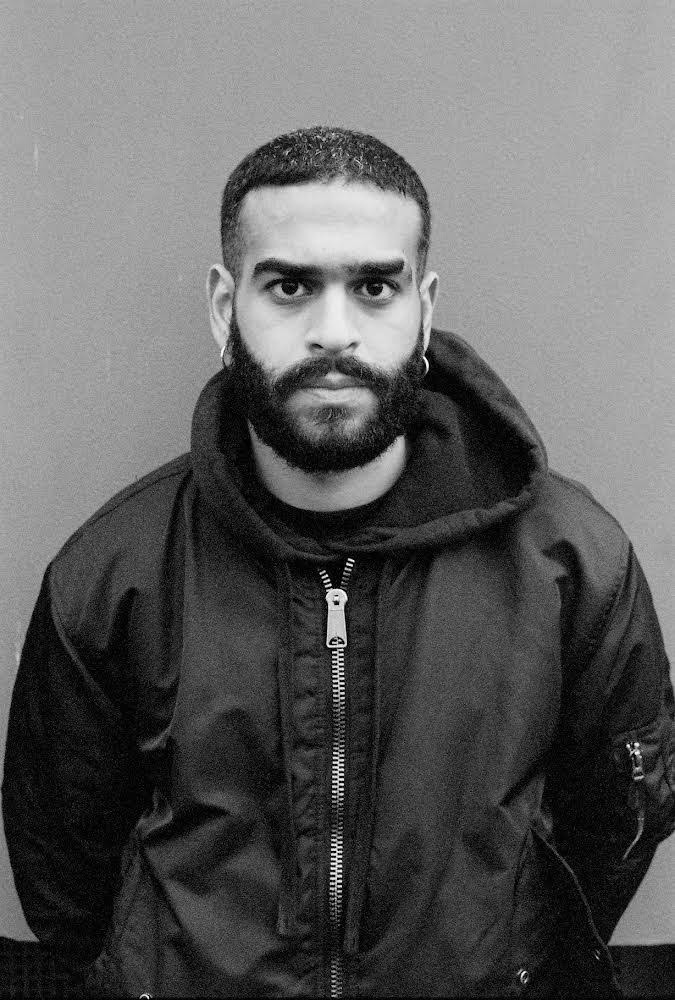

Adam, Thanks for joining me today. We’re lucky to have you for this issue and I’ve been looking forward to our conversation. I want to start by asking you about how you all met. I’d love to hear about your individual backgrounds and journeys, and how you came together as OKOLO.

Of course. We really appreciate it too. It started when I moved to Prague in 2005. I moved here to study Art History at the university, so my background is in Art History. I’ve always been a curious person. I’d always go around and try to meet people. At that time I was, of course, studying, but I was quite into BMX bikes, actually, bicycles in general. This is quite a strong connection between all of us. I went to my classes in university and after that, in the evening or afternoon, I always went to some skateparks or street spots to ride my BMX. One day I met this group of guys that were even younger than me. One of these guys was Matěj, Matěj Činčera, who was still in high school. He told me I’m interested in art and want to study graphic design. We realised we liked a lot of the same stuff. So we started to go out for beers and taking about doing some projects together.

«This lead to the idea of OKOLO coming around because OKOLO means “around” in Czech.»

We wanted to express that we were interested in the things that we find in everyday life, things that we like and admire . Whether it’s the design of bikes, furniture, artwork or architecture, anything. So we said, ok, let’s start some projects. We started to make t-shirts with some illustrations of real design objects on them. These t-shirts came with a text, with a story of what was on the t-shirt. So these t-shirt’s were a curated selection of some specific objects from design history. This was the beginning of our approach, and I think it’s still rooted in the same idea that we always want to present something from design history in a new way, through a new contemporary curatorial and graphic approach. Then we made our first issue of OKOLO Magazine in 2009. Basically that’s the year that OKOLO started, and at that point it was Matěj, My brother Jakub and I. My Brother was is crazy for bikes. He’s probably one of the most knowledgeable guys around bikes and bike design.

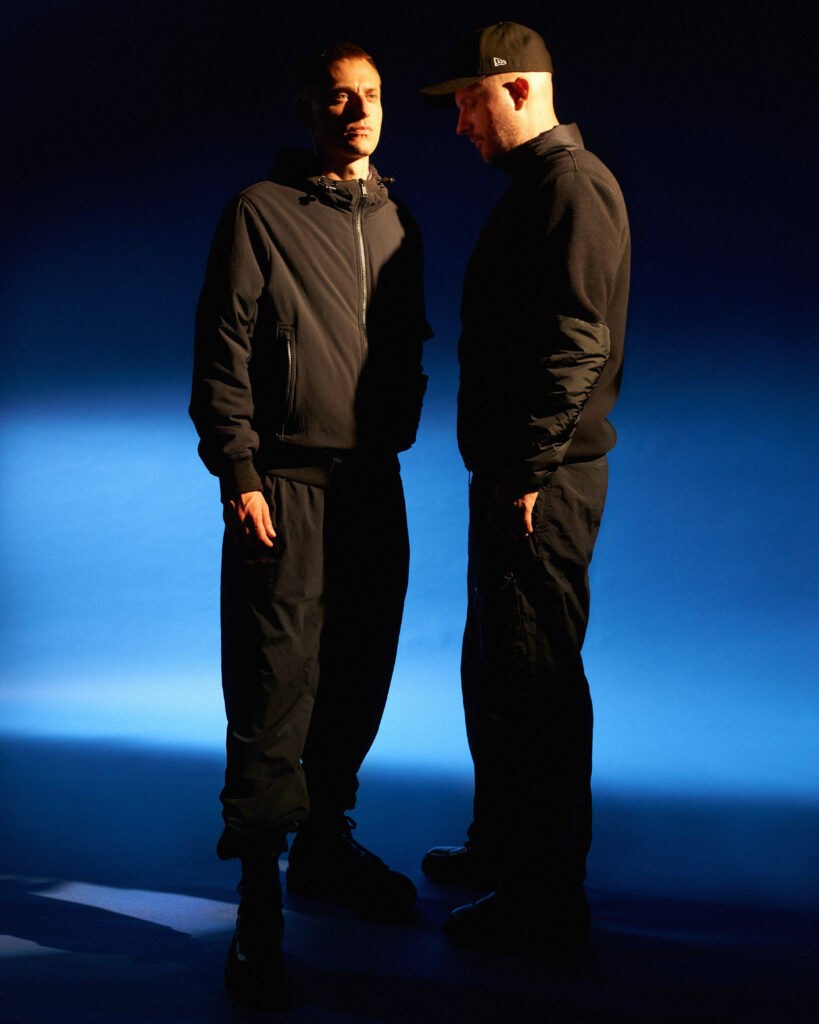

A few months after we met Jan Kloss. Jan wasn’t really from the BMX community but he was more into skateboarding and rap music. Both of these are also very close to me. I loved skating for its lifestyle, and we were all really into rap, groove, funk and soul. It was really great that we all met like this and had a similar vibe and sense of humour, and had the same values in our lives. What was important was that we each had different skills. I’m the curator. I’m the guy who writes the content and comes up with concepts for our projects. And Matěj and Jan are graphic designers, but slightly different from each other. Matěj’s much more into working with materials. He works with paper to create handmade installations, but also makes objects out of paper. He’s really skilful in this because his father was a packaging designer as well. And Jan’s more into the visual side of graphic design, not only creating logos but coming up with visual concepts for our books and visual features for our projects. So this is a perfect match, as each of us brought something different to the table. This allowed us to work independently as group and create everything in-house ourselves. This, I think, is our biggest advantage. But we’re really open as a collective, and do different projects on our own. I’m teaching and doing books with other publishing houses. Jan has a sneaker brand called PÁR, which means “pair” in Czech. Matěj is also teaching. So there’s projects that we do completely independently, but if there’s an opportunity for all our skills to connect and it would benefit a project, we always connect and do it together.

It’s interesting to hear how far back you all go and what interests your relationship is rooted in. I can visualise a trajectory of the different points and happenings that connected you all, it’s meaningful to hear how that relationship has built up to shape the dynamic you share.

Exactly! it’s really nice that we’re really good friends. We can really party together, we can see each other and hang out in any situation. It’s really like we’re kind of family. But In the last few years we don’t get to see each other as much. Jan has a family and Matěj lives a bit outside of Prague, so it’s nice that the bond between us is very strong.

It almost sounds like a mechanism that you’ve developed together, that you can rely on. It’s an established dynamic that you can activate when something comes around that you can all work together on. Even if you’re all doing different things and living in different places.

I’d say it’s basically a system, you know, If someone approached us with a brief, we already know how to process it, how to approach it and start developing concepts together. So it’s really an intuitive process for us.

We talked about your interest in BMX bikes, but I also wanted ask you about your lager brand and your exhibition about bottle openers. One of the things that I found interesting, which you touched on, is your approach to curating your shows. You seem to have a collective emphasis to re-introduce objects in a new context or alongside other objects, to give them a new meaning or narrative. Can you explain why you gravitate towards this approach when re-introducing these objects?

I think mostly the topics we are curating, we are choosing just because we love them. You know, for example, this bottle opener, this idea was born sitting having beer because we really love drinking beer, you know, and we laugh and have a good time during that. Also, this idea connected with the opening of our new gallery and studio space. So it was perfect idea to open our new space with the exhibition of bottle openers. Small things, you know, nicely designed, which have value and are everyday life objects. But they are really beautifully made and beautifully designed.

«For me as a curator, it is interesting to always choose a topic, do research and then show the broad spectrum of the topic. All the versions of all the incarnations of this topic as possible. It’s always based on this process of choosing something familiar, but to show it in a selection, which nobody would’ve put together.»

We like to really make this effort to choose different examples. Bottle openers or lamps or whatever, and to make a story, that somehow links in between them and then presents them in, let’s say, a fresh way.

I’m coming from an academic background, but I’m not really academic. I don’t like it so much, this academic environment, which is very traditionalist and old school in many ways. We always wanted to educate, to bring this academic information, interesting information that is not well known, and to present it in completely not academic way. To present it in an almost new contemporary way to the public. Because our public or our people who follow our work and they are not academics, they are basically designers. But of course, designers, they do their own work and they don’t always have time to study books and read books as I do for example. So I always wanted to spread this information, which I have in my memory, in my design research, and to present this information in a catchy new way that is also understandable to people who are in the scene, but also people who are completely outside of our discipline.

It’s almost like you’re creating a new vocabulary to re-introduce your research that feeds back into the system you talked about earlier.

It’s also very personal. We always have a lot of passion. It maybe can sound a bit cliche but the passion is the most important thing that you can have in what you are doing, whatever you are doing. It’s something that drives us. Even it’s a small exhibition in our gallery in Prague, where few people come to, or if it’s Triennale di Milano, like one of the most prestigious events in design. Basically, all our projects are on the same level, let’s say, because we love them all. We’re presenting this interesting information and stories of design through our personalities.

I think that reflects what you mentioned earlier that you love all your projects and that passion in a way is weaved through all your processes, whether it’s for bigger or smaller projects.

I know one of your passions is modernist architecture. I’ve been following your instagram account for a while and you have a nice collection of modernist gems on there. Where did this interest start and how does modernist architecture as a global movement but also in the Czech republic influence the work you create. I’d love to hear your scope on why it was pivotal as a movement and how it has evolved through different happenings over time.

Mhm, I think the 20th century’s the golden age of design and architecture. It’s the time when all these amazing movements came from and they were really idealistic. They were utopian and were very optimistic. I think it’s seen and felt through the objects. I kind of miss a bit this idealism in contemporary design. This idea of a bigger goal, and to create really the new society, the better world. Modernism is basically about that. It’s the movement which originated as a tool, used to show us how our society could grow better. The tool that was accessible to more people and they could afford quality products which help them in their everyday life. So, this is what I think is really extraordinary about the modernist ideas.

I’m kind of a retro person, so I’m not really as interested in contemporary architecture as much as the 20th century because there’s something in it, some special atmosphere, some charm, which really attracts me to it. You can tell these stories. You can read the stories. So for me, it felt natural that I focused on the 20th century design because you can feel the diversity of design. What was done in Scandinavia is different, and what was done in Brazil and in Japan is different, but everything is somehow connected under this big idea of of modernism. It’s like picking some chocolate from a bonbon. You don’t know which is better, and you want them all basically haha. For me, modernism is this period that I can really find so many beautiful forms, shapes and materials, and all its architects and designers across the world. And it’s basically an endless source of of stories for me.

For 15 years, basically even more, like 17, 18 years it’s been a constant for me. A constant study of 20th century design and architecture. In my head I have a huge archive, and it’s something that you can always find something to explore, something new. I think in last ten years, and maybe because of our work a little bit, it’s got a popularity among the public, and suddenly you see that brutalism now’s quite trendy. People are travelling and taking photos. Now it’s become a thing our generation has started to re-discover, and it’s great that even the people who aren’t really geeks like me are discovering this, and they find some beauty in it. Social media and digital publications have had a big part in this as well. I think it’s a good time now to continue in this because it suddenly has much more of an audience than before.

Although at first, your instagram account focusing on modernist architecture seems separate from your work as OKOLO and from your separate studio account, once you look deeper you realise that some of your projects find their roots in this obsession. For me Mood-boards, and of course, your publication Modern Architecture Interiors are evidently bringing these two worlds together under one umbrella. I want to ask you about your process and experience of putting these projects together with Jan and Matěj.

You mean Mood-boards for Vitra?

Yeah exactly!

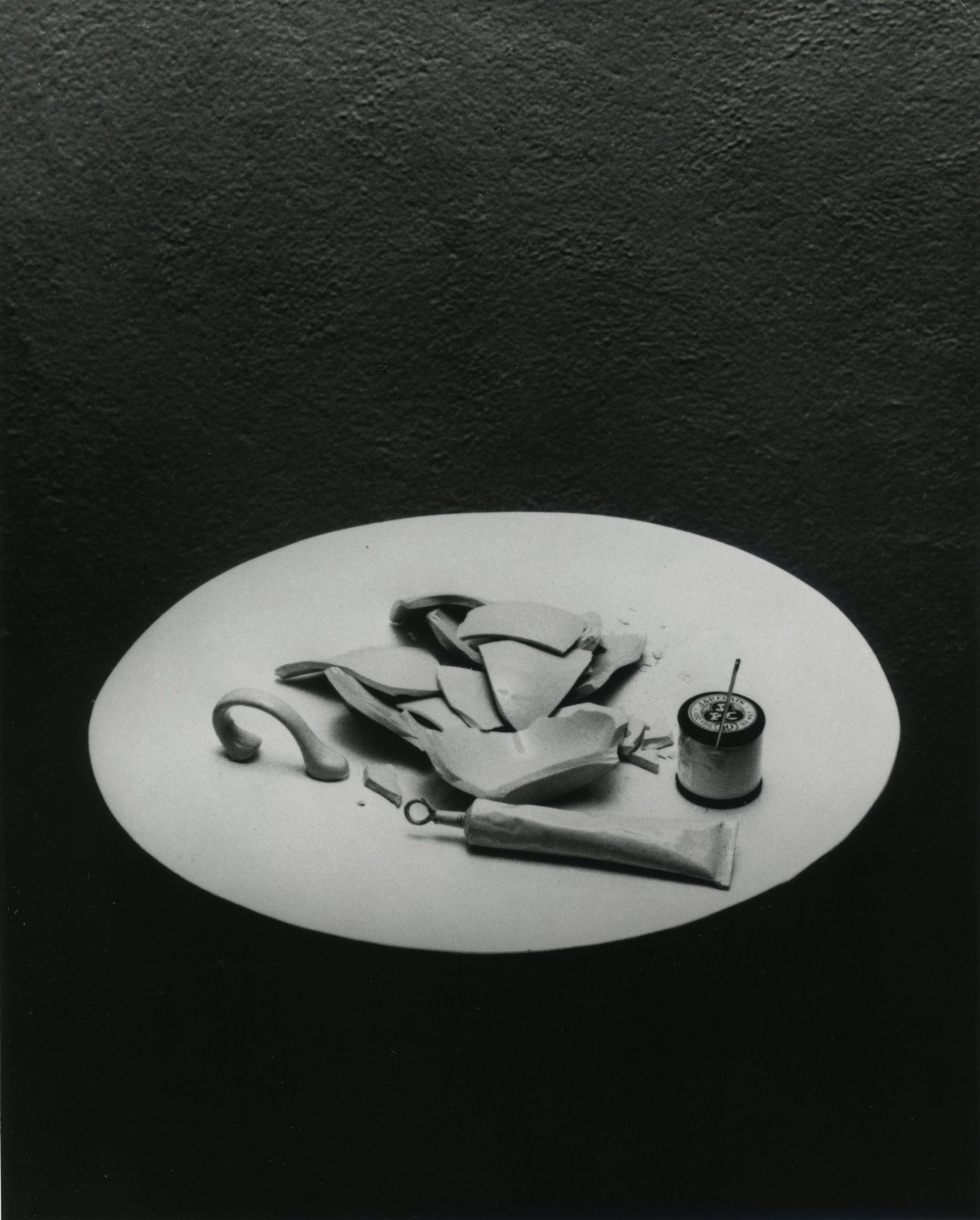

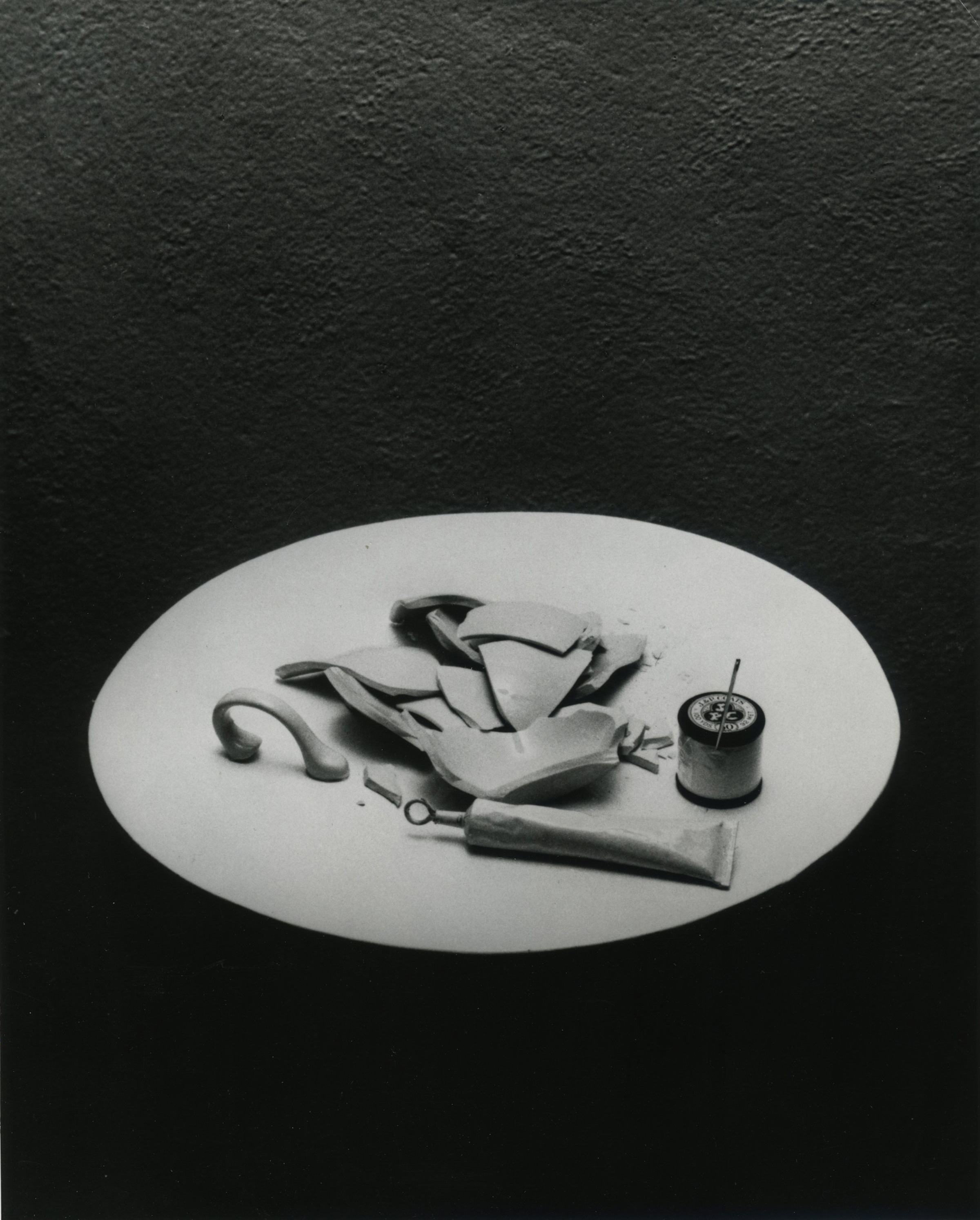

Yeah, that’s the perfect example of how we can connect our skills. Because the “Mood-boards” project came up because I was asked by a curator in Vitra Design Museum that they’re doing this exhibition called “Home Stories”. It was about interiors set in different periods and different countries showing the evolution of the domestic space. They asked us, so you’re a curator and a theoretician, but you work with your colleagues. Maybe you could do a project that will be on the edge of research and some form of artwork. So these mood-boards were really a great idea because I could connect my knowledge from visiting houses to them. We chose three houses, which were “Villa Tugendhat by Mies van der Rohe”, “Villa Müller by Adolf Loos” and “Villa Beer by Josef Frank” in Vienna. And I visited these houses properly once again to research all the materials which were used in them. Then we tried to get samples of these materials, as many as possible, and create some kind of collage out of them.

This part was more the work of Matěj, because he really was able to work as a sculptor, to put all these samples together in a nice collage structure, which you can put on your wall as an artwork. But if you read the caption that comes with it you find out that it’s an exact imprint of a real iconic interior. So this project is a really nice example of how we connect our skills. For example, this project took about ten months to complete, and for the first months I traveled all around visiting these houses. I took all the pictures and documented all the details. Then I also visited some experts who would really tell me, yes, this marble’s this kind of marble. It’s not Carrara marble, but it’s a marble from Switzerland or so on. I gathered all this information and produced this research and I passed it onto Matěj and he created these mood-boards as a visual and as our art piece. It’s nice that these projects have different timelines for each of us. Mostly, I always work in the beginning on the concept and on the research and then the work of guys is starting in the second part of the process, when they’re starting to do the graphics and how this research will be displayed or how it will be conceived.

Regarding the book for Prestel – “Modern Architecture and Interiors”, this book’s kind of a Bible for me. It’s my little Bible. It’s 15 years of travelling and visiting architecture. It started with me travelling and visiting many, many houses. I always wrote some articles or made some small exhibitions about it. But I never put it all together. So in 2018, I started thinking, okay, I have so many buildings which I’ve visited, so maybe it would be nice to put everything together and do a really huge book. Then we met Lars who is really nice guy, Lars Harmsen. He is editor in chief of Slanted magazine. It’s a graphic design magazine. Very strong magazine.

Yeah I know it. It’s a great magazine.

Harmsen told me, Oh, if you have such a big archive you should do a book for Prestel. I have some friends there, I can connect you and maybe they’re interested. I reached out and they said they were interested. So we said, ok, let’s do a book and I started gathering everything, all my archive. I realised that I have maybe 1500 houses already documented and I selected 1000 of them. I decided to approach the book as a starter pack in the sense that you don’t have too much information there, but it can motivate you to find out more. So it’s kind of a crossroad for different readers, suitable for deeper research for every single reader. We decided to do a book layout that would be understandable, which would also be efficient. We discussed it together – as OKOLO, and we said, okay, let’s do one building per page from A to Z – in alphabetical order. Jan created this layout, which I found to be quite universal. Then everything was ready to print, and Prestel told us we can’t print a 1000 pages and we needed to reduce it. They said you have to reduce it by 200 pages. That was a really sad moment for me, so now it’s just under 900 pages. I also had some issues with copyrights. Of course, all the pictures are my own, but there are some architects like Le Corbusier or Frank Lloyd Wright, which charge you a lot of fees, so I quite often have to edit out a lot of these pictures I took because the fees would exceed thousands of euros.

Yeah that’s always a bit frustrating. This book to me incapsulates such an extended period of time of research and a beautiful form of obsession, even if it’s a reduced amount. Hearing you talk about these two projects, you can understand how you individually initiate projects and later in the process come together to collaborate on the delivery of the project. They also highlight your relationship with the community of creators and collaborators around you.

I guess this would be a great point to ask you about your ten year anniversary book. I found the layout of the book quite interesting and very much in tune with the story behind the process you just explained for these projects. Half of the book showcases your work as a collective. The other half your individual work and personalities, and also your relationship with your community and collaborators. Can you please speak about the story behind choosing this format and your experience of putting this project together.

For sure! The format was actually Jan’s idea. We had our anniversary party in 2019, and it was quite big. Many friends came and it was fun. After we said, okay, that’s it. We did a party. We won’t do a book. We were thinking about a book, but we said we have a lot of work and thought we didn’t have time to do a book. But then, like few months later, Jan came because he’s totally a workaholic, and said “hey, I was thinking we should do this book, let’s do this book! I have a really great concept. Let’s do two parts for the book. One part will be about our work, and the other part will just be about our life, our friends and the people we’ve met. I said, that’s great, I think we should do it!

So we gathered all the projects we made, even some really small ones we almost forgot about. Also, we all went through our photo archives and found these crazy pictures from the parties, from the openings and from travelling. It was really great that each of us had different pictures from different memories and projects. I think this is what exactly characterises us. That we love our work and we can even sometimes show it off, you know, and that we did this nice book. But I think maybe even more important are these moments meeting amazing people that share the same values and the same interests as us, who have many stories to tell. So all these great people, it’s so joyful, and we’ve been very lucky to visit and work with such amazing artists and designers. It’s really something that will be in our memory forever. When we sometimes go out for a beer together, we always talk about them. these rare memories are very, very valuable to us. This book is perfect for when someone’s visiting our studio, and we’re like we did this book and you can see our projects. But the most funny thing is from the other side, where they can see our photos from the from the parties and from back in the days when we were much younger. You can see it’s not a really difficult concept to do this, it’s basically very basic. Maybe in general, We really don’t like very complicated curatorial concepts. I think we’re kind of straightforward in this way.

It’s crucial this idea of going with what’s closest to you, because so often when designers try to showcase such an expanded period of their practice and careers, it becomes a very serious conversation. To me, this can result in over complicating the conversation and making it less digestible for a broader audience.

Also, I think there’s a lot of value in the side of your book that exposes your personalities and interactions with your community over this period. As a reader, viewer, designer, or whatever, I find this humane side of your book much more tangible and relatable. I appreciate that you’ve opened up this side of your experience in such an honest and simple way, and dedicated such a big portion of this book to it.

It’s also visible when we go somewhere to do an exhibition or something, and we arrive and they see three smiling guys, and I think we have a bit of a charm. I think they can see the passion in us, that we are dedicated to what we love, and this somehow opens doors for us. That we’re authentic and we aren’t pretending something. We can be at some crazy posh design week party, and we’ll still act like us. Super chill guys from Prague that like to drink beers and hanging out with each other. We gravitate towards the same people who are authentic and true. I have to say I’ve been super lucky that the people I’ve collaborated with were all really good people, and I think this is something that truly imprints into your mind and into your heart. Sometimes, you know, there are so many pretentious things in our discipline. This is something I’m really not interested in, and as I get older and older I kind of get angry at these people, like what the fuck, be normal, you’re not the star, haha.

I definitely get that haha! I think the reason you’ve connected with the people you have has a lot to do with where you stand individually and as a collective. Over time your position and work asks the questions that interest you and attracts like minded people and partnerships. As someone that is only at the beginning of that journey it’s inspiring that over 15 years you’ve managed to keep your values so close to you and how that’s surrounded you with a community of likeminded people.

Yeah, thank you very much, I really appreciate it! I really do.

Touching on your collaborators and relationship with your community, I want to ask you about your work with Maria Cristina Didero and the exhibition, Designers, and the publication, People, you created together. It’ll be great to hear about the research you and her did together, and how Matěj and Jan visualised this research.

It was funny. We were in touch with Maria, but very lightly. We knew each other somehow, and we were in touch via email. For our gallery in Prague, we always like to invite designers that we’ve met before to come and exhibit there. We’d say we don’t have any money, but we’ll cover your flight and accommodation, and we’ll give you this space to do some cool project together. We’ll have a nice opening and have fun during the party. Basically, all of these designers that were invited were like yeah why not, let’s do it! And when I see them again, sometimes years later, they always remember those memories, and say they had fun in Prague with us doing these projects. It was the same with Maria. We were like let’s invite a curator, instead of a designer. It would be interesting. So I wrote her an email saying that I wanted to invite her to prague for a lecture and an exhibition, and she said “yeah, I’d love to! But what is the exhibition that you want to do?”. I had a spontaneous idea and I said because you’re not a designer but you’re a curator and writer, you can showcase your writing. What if you choose your favourite designers that you’re writing about, and we’ll – OKOLO, choose a specific part of the text and we’ll make some graphic posters out of them. And she said I love it, let’s do it! So I kind of became a curator that curated a curator haha. I curated Maria’s writing and it was so nice. I shared this with Jan and Matěj and we decided to do some posters and visualisations of the designers work that Maria was writing about, and these came as a visual representation of Maria’s work. It was a really fun opening during Designblok – Prague-based design festival.

A year after Maria asked us if we could do a version of this exhibition in Milano, and we did “People” as a catalogue publication for this exhibition. We added some more designers for this exhibition, and we created more illustrations. And also we completely changed the media. Instead of posters shown in Prague, we decided to to a special publication with these illustrations. We did this for Mostro, which is the graphic design festival in Milano. We invited her first to Prague, and this resulted in her inviting us a year later to Milano, and it’s really cool that this lead to this project having some kind of evolution.

That’s really interesting to hear how this partnership lead to a friendship and an on-going collaboration.

I want to finish by asking you about what you’re working on now, and also about what you’re looking forward to in the future.

The Triennale is the project we’ve been working on for the past year. It’s the official Czech presentation at the Triennale di Milano, which is a legendary event going since the 1930’s. The main topic is “Unknown, Unknowns; Introduction To Mysteries”.

We were asked by the Czech Museum of Decorative Arts, which is the organiser of the Czech Pavilion, If we’d like to curate something under this topic. So we created an exhibition that we’re opening next week, which is called “ Casa Immaginaria: Living In A Dream”. It’s about the phenomena of “Dreamscapes”. During the pandemic there was quite a rise of this new digital phenomena, of creating fictional interiors of fantasy-like living environment, as a form of visual perfection or even fetish. You can relate that we were sitting in our homes during the lockdown and we were dreaming and fantasising about these dream-like environments that we wanted to be in and escape to.

And I think that’s part of the reason why this Dreamscapes phenomena came about. So I got in touch with some of these designers that create these Dreamscapes, which mostly call themselves digital artists. I thought this was a great topic for the theme of this show, focusing on this idea of escaping to some unknown world through these images. We did this installation that we printed these large more than 2 meter format prints mounted on light boxes, presenting this new phenomena of Dream- scapes. We added real metal constructions in-front of the images which work as an extension of the fantasy world into our reality, which symbolise the border between reality and fiction. Also, we’re presenting some historical context of fictional houses and interiors, in a similar process to our previous curations. We made a catalogue as well, and next week is the opening of the show. It’s going to be a big event with the minister of culture attending, which we’re really excited about.

That’s super exciting, and it touches on a feeling that we all collectively experienced and a period we all went though. This imagination that came out of our isolation, and presenting this section of work in this format is introducing them to us in a new light.

Yes, exactly. So this was our last project and now we’re doing a museum exposition for the Czech furniture company TON, which was born out of Thonet. It is a company that is now based in the original factories founded by Michael Thonet in the 1860’s. They produce handcrafted bent wood furniture using steam. We are curating a retrospective of their portfolio. I actually did a book for them and that’s were this project started – the book was not an OKOLO project, it was done with their own graphic designers, but this exhibition is our collective project.