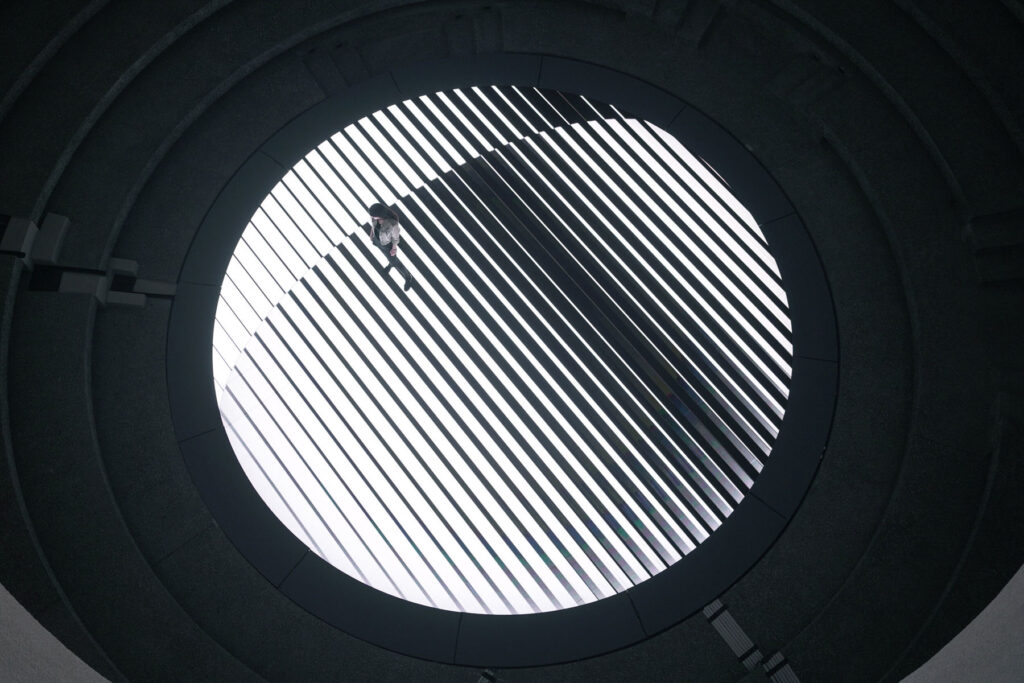

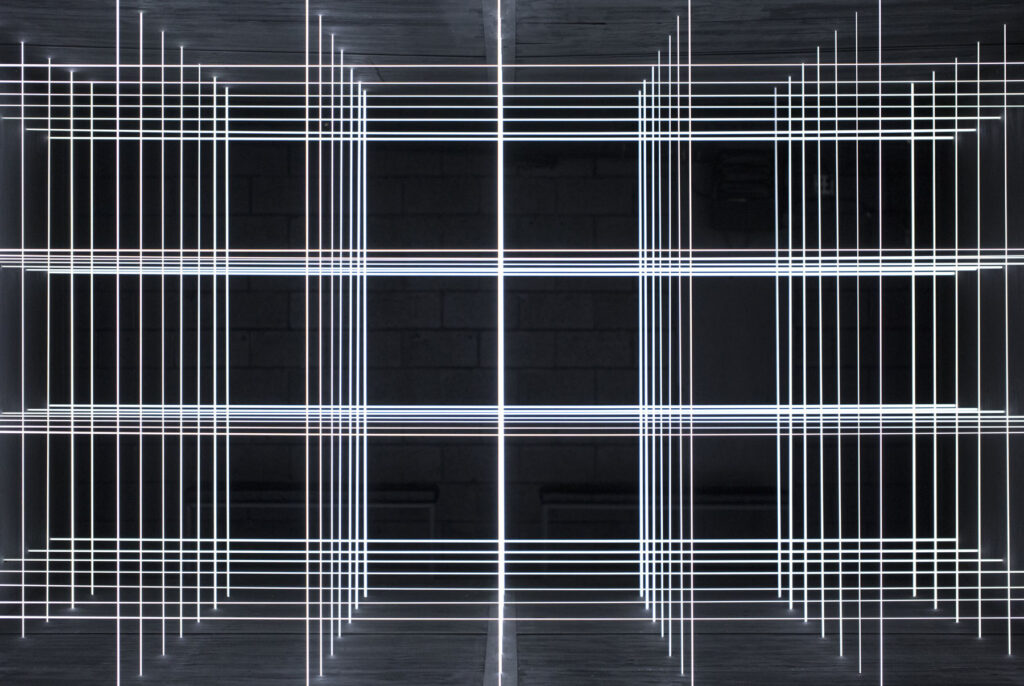

The first time we were able to experiment on this new concept was during the few days we had to set it up before the opening of the exhbition. We had preparations and expectations in our mind before coming but the first day we were there we just realise the effect wasn’t working as planned. We had to change everything, move completely the position of the projectors inside the room and start from zero all the composition of the visuals at the last minute. It learns me how important it is to be in front of the piece when you program it and how dangerous it could be to work on something by simulation when it comes to something as sensitive than light.

TN: This is actually one of these projects that really drew a line on the approach and the personal relationship we have with the work we create.

We realized that imagining projects in small scale or simulating them was helpful to visualize projects but nothing felt more real than getting to our exhibition space, spend time with our new piece and work on the composition in relation to the space. Living within the project and make it an intense experience. That’s how we like to experience our installations, and we should never forget that the reason we started all of this was because of our love for materiality in light, and we do think this can’t be replicated virtually and we treat it as a material in itself.

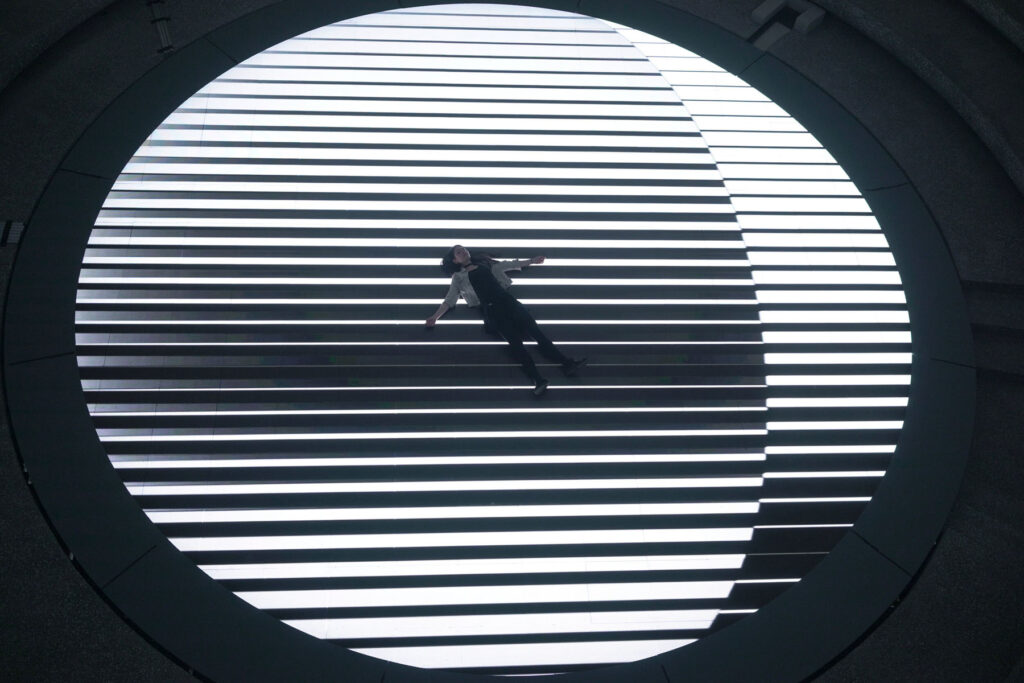

Your 40 minute audio visual piece SHIRO was ranked by the New York Times as one of the top 15 performances at Sónar Electronic Music Festival in Barcelona in 2017. I could not find the whole performance online but watched various extracts from it. In contrast to your other works, you both are taking part on stage so to speak in the performance. How did that feel? Would you want to do more of those kind of perforrnances in which the public get to actually see you?

You have performed this piece in different places over the years, was there any in particular that you keep a fond memory of and if so, why?

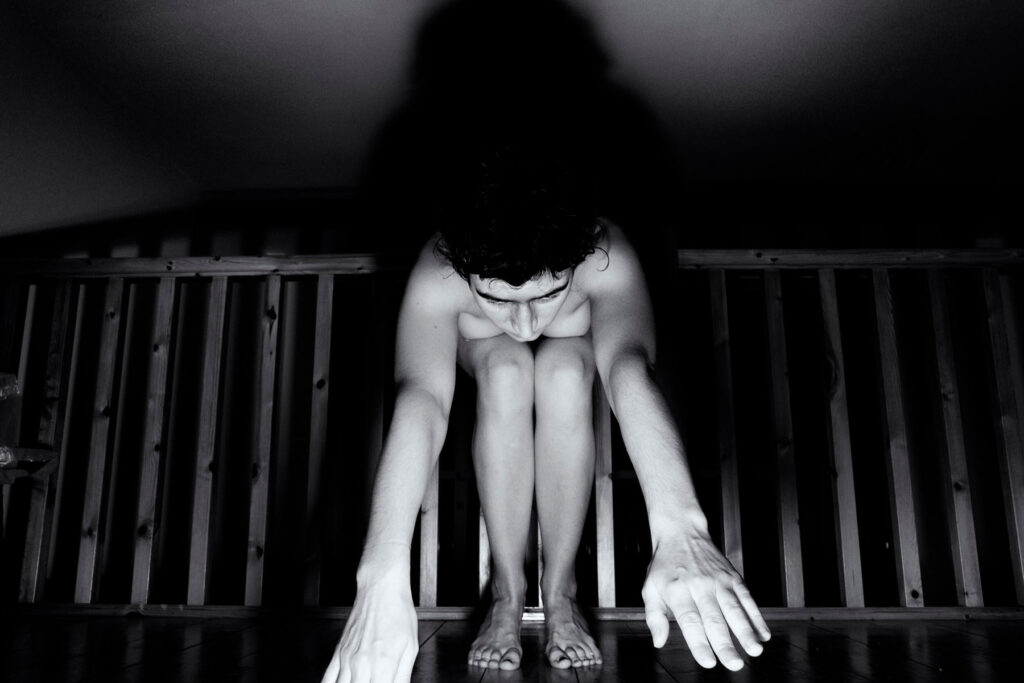

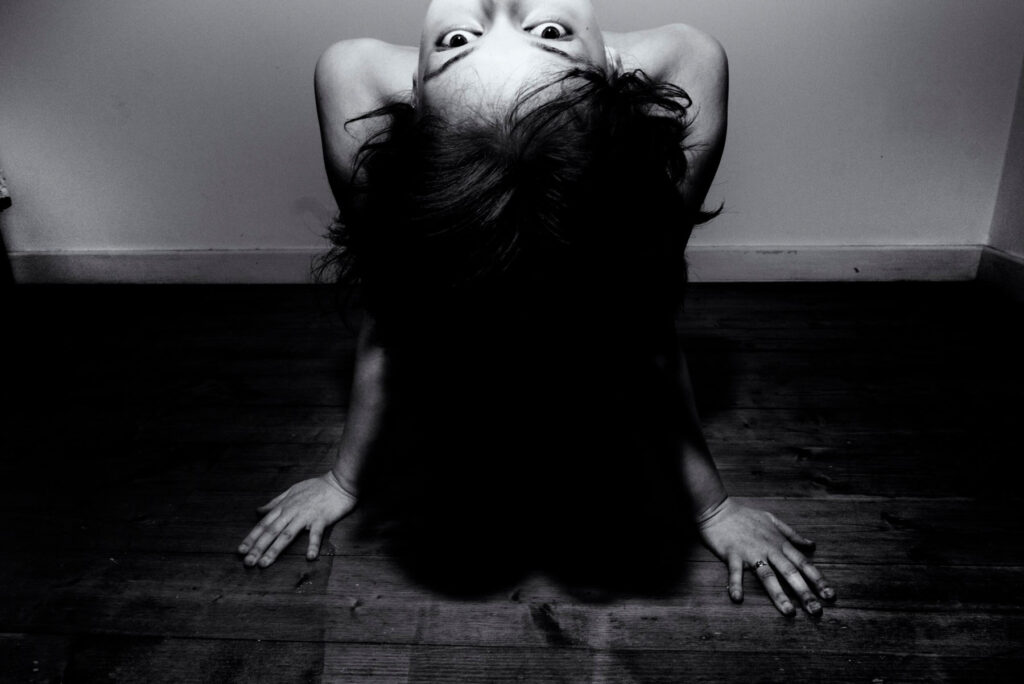

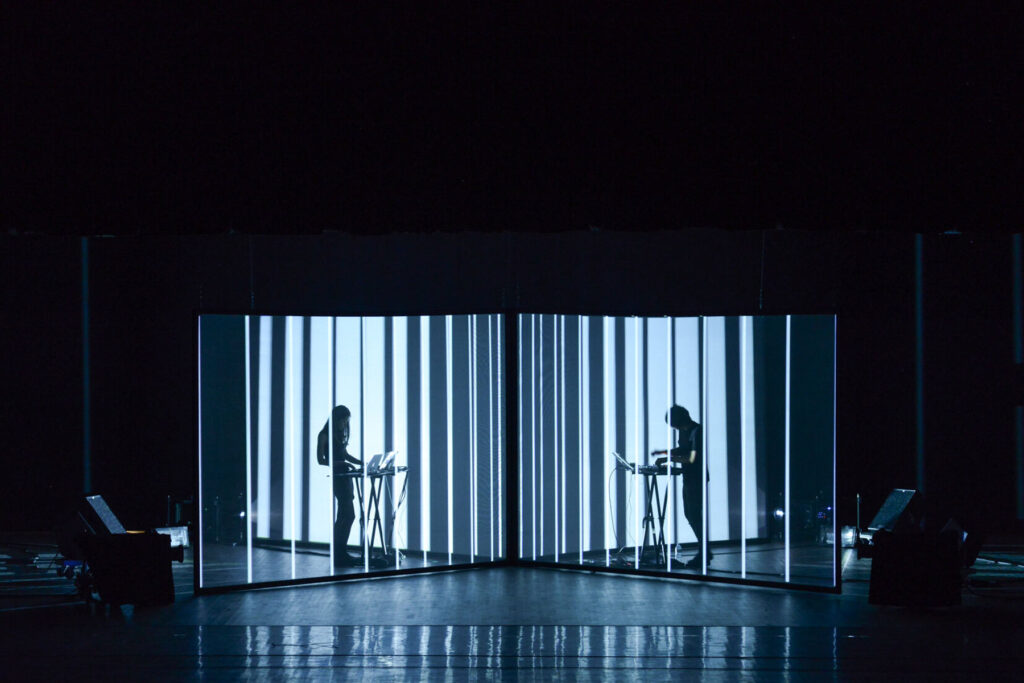

NS: When we were working on our installation we also realise it was cool to see people silhouette passing through it. The relationship with the human body scale and the installation was interesting. Tak as a musician was interested to extand his background in electronic music. That’s how in summer 2013 we worked on our first performance called LATE SPECULATION. The concept was us performing inside a translucent structure with 2 projectors and use our silhouettes as part as the visual effect. One projector was placed from the front and the other one in rear. By alternate which projector was on, we were making a visual illusion of us appearing or disappearing. SHIRO is our second performance in continuity with LATE SPECULATION.

Installations and performances are really different experiences. The first big difference is the fact that we are sharing the same moment with the audience and have a direct reaction from them. The dynamic is really different. It’s really powerful to hear the audience during the show.

TN: In addition to Noemi’s answer, I think we simply like the fact to not really limit ourselves to installation artists but also performances where music takes another dimension and also the way we directly interact with the audience and experience something in real time with them.

Stage is a special and unique place to express yourself and we enjoy switching from installation projects to live performance projects.

The 2019 pandemic in which we are still in, has obviously impacted quite harshly the arts and performances industry. The past year has definitely been difficult and for some more than others but I feel like we have all in some sort and in different capacities being able to plant the seeds for the present year. It feels as though there has been a lot of self-reflection and introspective work done at an individual level which will then enable growth, which is the theme of this issue. How do you both feel with this? How does Growth resonate with you?

NS: During 7 years we had the chance to be able to live for our art and been able to showcase it in so many extraordinary places. I would be for ever grateful for this. The rhythm of our travels, exhibitions, live shows was intense and we never really had breaks at all. When we had our first show cancelled and the first lockdown was announced I was a little bit puzzled but at the same time for the first time since years, I would have a break and time to step back about NONOTAK.

Now that it’s been a year we are in this situation and seeing how it evolves I’m more than sad and anxious about the future. With NONOTAK what drive us was the experience, the moment, to feel physically connected with a space, exchange emotions with an audience, share a stage with people. And when I see the art scene going more and more only online it deeply depress me.

TN: That “covid” crisis really affected the touring dynamic of our collaboration and it is pretty sad, but we know it is also reflecting in many other people’s lives. That crisis gave us the time to reflect on ourselves, the meaning of creating art especially in this type of context. But it also gave us the time to reflect on society and the power the government has over people’s lives and their freedom but more importantly, the way they are able to fragilise culture and normalize it out in the open.

Questioning the narrative became politically incorrect, aspiring for freedom makes you feel guilty and this is the society we allowed ourselves to live in. What kind of future does Art expression have in this “new normal” we are submitting to? I don’t really know about that. But it seems to me that being a sovereign individual is the starting point of any form of expression and we feel like we are totally losing the value of what it means to be free. It is pretty scary to me and I guess it is for many other people.

I think growth is still possible in this context. being adaptive is key to finding a path you feel comfortable with in terms of creating and growing. Since “covid” started we got ourselves in projects that required lot of learning and we at least feel like we took advantage of this a little bit. We don’t know when we would have stopped touring without any interruption if this did not happen as well.

We are doing this interview during the first few months of 2021 and the issue will be released this spring. Are there any projects you are looking forward to be taking on and that you could share with us?

NS: We are working on permanent installations that will take place in 2023. It’s a different challenge than working for events or temporary exhibitions but really exciting about the idea that the piece will last for ever.