«A slow-motion carbon time-bomb we are dropping on ourselves and all of Nature»

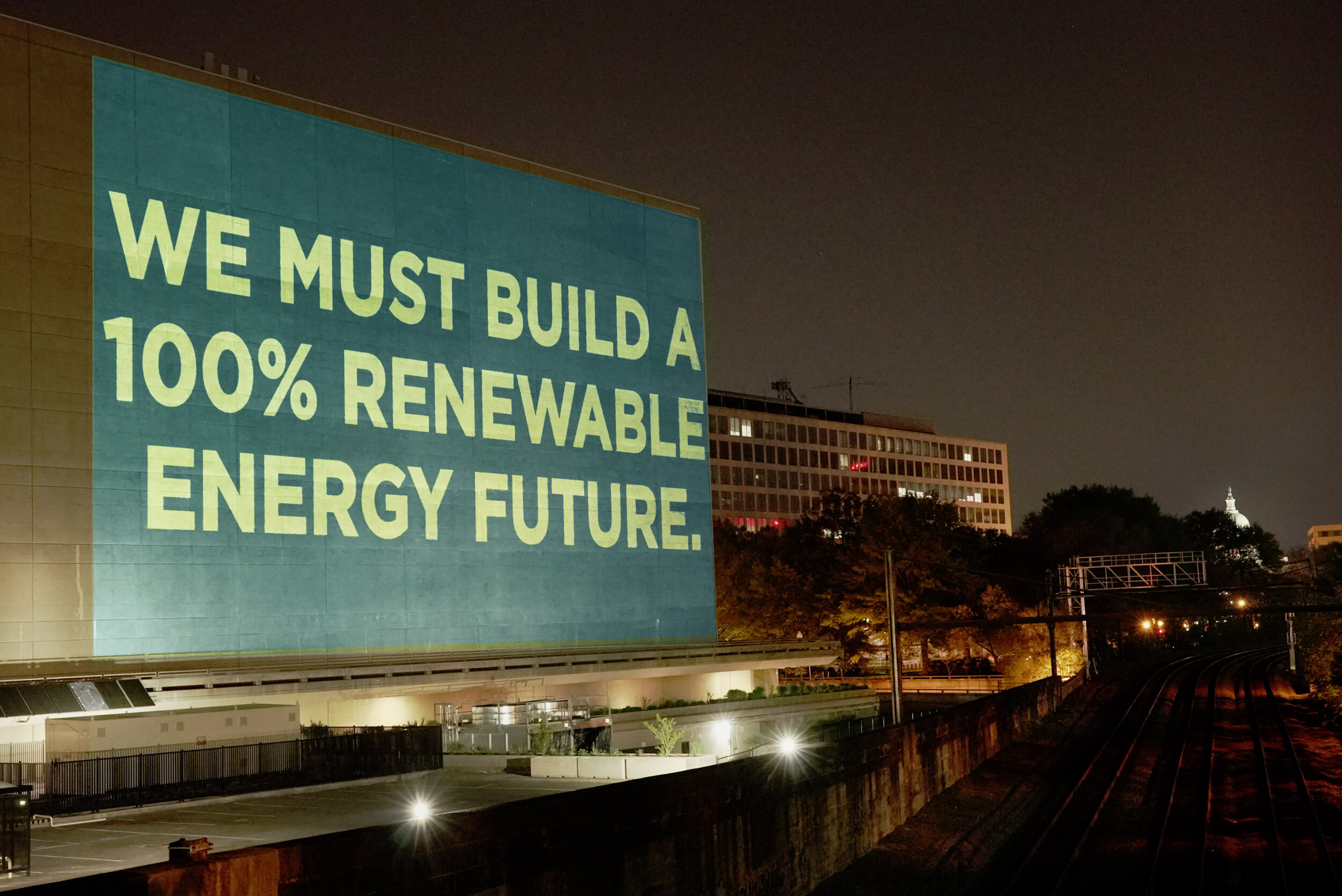

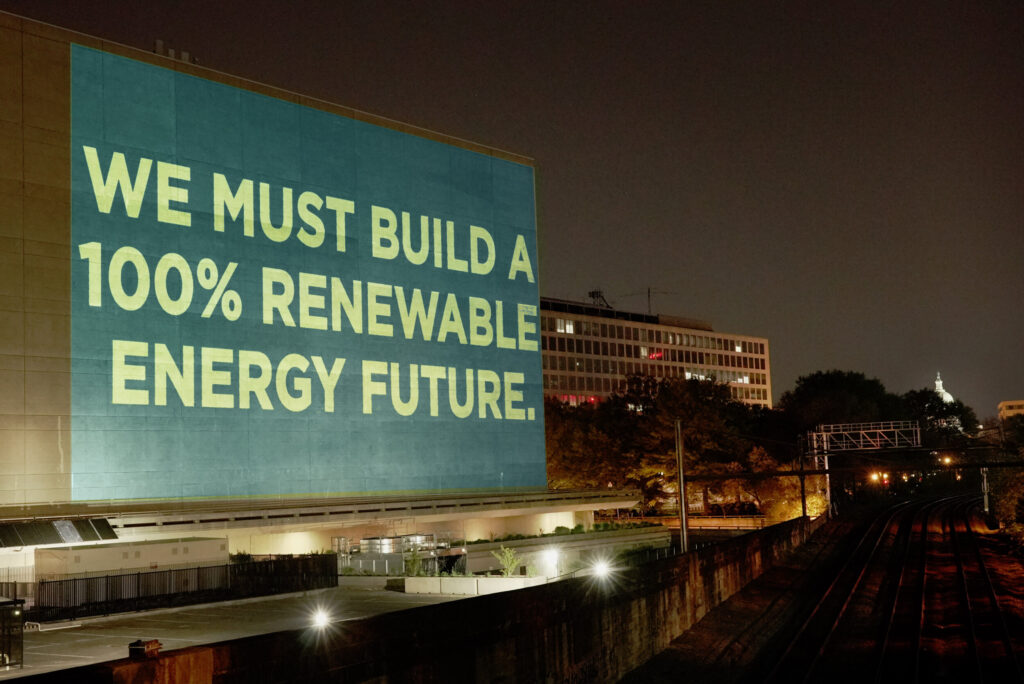

At the time of writing, there is six years, 267 days, 16 hours, 25 minutes and 57 seconds to stop the clock, so to speak, before the environment faces catastrophic events. Of course, by the time this goes to print, that number will be less. And in September 2020, when two artists, Gan Golan and Andrew Boyd, unveiled their ‘Climate Clock’ in New York, there were seven years remaining. The clock, plastered on the side of a building in New York’s Union Square, shows two figures. The first, in red, shows the time remaining to reach the 1.5 degree target, set by the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change, which would provoke devastating environmental disasters around the world. The second, in green, shows the percentage of energy produced using renewable energy; our lifeline, as it were.

The clock replaces Metronome, an LED public art installation unveiled in 1999 by the artists, Kristin Jones and Andrew Ginzel, that shows the length of time to, and from, midnight in a 24 hour cycle. As it happened, the artists behind the original public artwork had been looking to address the climate crisis through this work. Utilising the existing technology, the display was temporarily reprogrammed for the duration of Climate Week, ending on 27th September. For now, the Climate Clock remains in situ – that is, of course, unless it reaches zero.

Following the birth of his daughter (igniting a sense of urgency around the climate crisis) Gan Golan approached Andrew Boyd, to collaborate on the project. They had previously made a Climate Clock before, but on a much smaller scale. Nine days before the activist, Greta Thunberg, appeared at the UN Climate Action Summit in 2019, the pair were approached by email. “Greta wants a clock,” it read. They were able to band together enough coders, designers, artists and the like to make the clock in time for the summit, which was ultimately barred from being brought into the event by UN security. As the affair is summarised on Climate Clock’s website: “Oh, come on! It’s just a block with LED digits furiously counting down. Does that really look so much like a bomb?! Oh. Right. Well, that’s probably because it is a bomb! Or at least the symbol of a bomb. A slow-motion carbon time-bomb we are dropping on ourselves and all of Nature.”

The launch of the Climate Clock in New York chimed with the world in a much bigger way than Gan and Andrew had perhaps anticipated. And in the six or so months since its unveiling, smaller Climate Clock initiatives have launched across the globe. The first clock in Kazakhstan was turned on in January, another is planned in Glasgow to coincide with the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in November, and there are plans for one in the Bay Area – to name just three. Climate activism is not a recent phenomenon, but the past few years have undoubtedly seen an acceleration in their coverage, influence and engagement.

The first Earth Day was marked on 22nd April 1970, during which 20 million Americans mobilised to voice their concerns for the direction in which the climate was headed. Every year since, Earth Day has taken place on the same day. The origins of Earth Day date back further, however, arguably to the publication of Silent Spring in 1962. The books author, Rachel Carson, rang the alarm bells that the twentieth-century way of life was having a devastating impact on the environment. Petrol guzzling engines; the acceleration of mass-production; the use of pesticides. Up until that moment, the world was somewhat unaware of the consequences of their behaviour on the environment, the eco system and on their own health.

Ahead of Earth Day 2021, NR Magazine partnered with Gan, Andrew and the Climate Clock team to highlight the urgency of addressing the climate crisis. We spoke with representatives from three of the satellite projects, in Kazakhstan, Glasgow and the Bay Area, to learn more about what drew them to the Climate Clock, and how their involvement is creating change within their local environments. The full video discussion, which took place over Zoom, will be unveiled on 22nd April, but below is a condensed and edited summary of the issues covered.

The three representatives, Meruyert from Almaty, Kazakhstan, James from Guildford, UK, and Kim from San Francisco, US, are all at different stages of their Climate Clock journey. ‘I saw the clock that they’d set up in New York over social media […] and it caught my attention,’ James explains. He recognised its huge potential to raise awareness about the upcoming COP26 summit throughout the country ‘because,

«not many people in the UK actually know it’s happening or what it is, which is not a good sign because that means that people around the world probably don’t know it’s happening either.»

For Meruyert and Kim, seeing the New York clock on social media helped sow the seed amongst their teams, too.

‘One of the team members, Galiya, found out that we could also put a Climate Clock in our city – in our country,’ Meruyert says. They began as a team of four, working to put up the ‘third biggest Climate Clock’ and the first in Asia. ‘It was crazy, it was huge […] And now, we’re doing new movements [and] projects in our community and getting into the eco activist life.’ Not long before the Zoom call, the Kazakhstan team welcomed their sixth team member. For Kim in the Bay Area, though, it’s currently just her and her friend, Hannah, involved. They’re still early on in the process, but are committed to doing something about the Bay Area’s lack of any ‘[real] substantial symbol of action towards the climate crisis’.

Though the ultimate goal of Climate Clock is to “flatten the climate curve” it’s interesting to hear the immediate concerns of the respective teams. The shadow cast by Silicon Valley over the Bay Area is one that needs to be addressed, quickly, for the local environment, as well as the world. ‘[These areas] have a such a large sphere of influence. There’s so many corporations and companies that can work towards a more sustainable future.’ Kim hopes a ‘butterfly effect’ will occur, and so her goal is to put pressure on those companies.

For both Meruyert and James, their action is aimed more at politicians. As James explains, the hopes for the Glasgow Climate Clock around the time of COP26 is that it will address the ‘huge disparity between current levels of political ambition and what needs to happen.’ The idea being that the clock will help mobilise the public, and put pressure on politicians to draft up seriously-considered strategies and policies; words that have actions behind them.

«We have a big problem, in the UK at least, with politicians talking the talk and saying things at these international summits, but then actually, domestically, not really living up to that.»

That’s a sentiment Meruyert shares, and it was the empty words of political leaders in Kazakhstan that energised the team to get to work. ‘The interesting thing is the people in political power say that they need to take action, but they want us – the younger generation – to save the world, to save the country. But they’re the decision-makers.’ This disconnect spurred Meruyert and team on; ‘that was the urgency. And after researching all the information we were like, “We must get it. We need to do it.” So, we did it.’

Another issue that all three teams have had to address is criticism that, if real change depends on political power, the Climate Clock only scares and intimates the public. ‘We’ve definitely had some tough questions and concerns raised,’ Kim recalls, adding that a community college she contacted about adding the Climate Clock’s widget to their website were worried it was ‘too similar to a Doomsday Clock and would actually push people away.’

After the installation of the clock in Almaty, Meruyert’s team approached officials in Nur-Sultan, the capital of Kazakhstan, about installing a clock there. The response was that they didn’t want ‘negative energy in big public places.’ But as all three point out, what’s more terrifying is the fact that the 1.5 degrees threshold could be crossed due to global inaction. ‘I feel that the climate issue [is at] a point where such an urgent symbol is needed,’ notes Kim. ‘We don’t have forever to fix the issue, and I think that the Climate Clock is meant to be intimidating because it’s supposed to pressure people to take action.’

Collaboration comes before fear-mongering, within the Climate Clock community and beyond. The teams meet virtually every Wednesday with Gan and Andrew and have access to training and mentoring to help them get their local campaigns off the ground. Kim mentions that herself and Hannah, for example, received advice from the Kazakhstan team on how to reach out to local partners. Unlike Kim and Meruyert, James has been a climate campaigner since the age of 13, and the team in Glasgow have also had discussions with other climate activist groups in the city and beyond, including Fridays For Future and YOUNGO, the UN’s youth climate constituency.

Acknowledging his relative experience as a climate campaigner, James asks Kim and Meruyert whether they’ll continue to be involved in similar work after Climate Clock. Both agree that, in one way or another they will – because the issue isn’t just going to disappear. But as we approach Earth Day 2021, what do the three team members hope to have achieved by Earth Day 2022?

‘I hope we’ll have managed to successfully use [the Climate Clock] to mobilise young people in the UK ahead of COP26, and managed to push for ambitious enough action – and start to have that filter through into policy around the world. But hopefully, we can still use it to continue to generate momentum around the country and the world to hold politicians accountable to the decisions they’ve made at that summit, and make sure that actually translates into physical action rather than just words that were spoken that once, in November in Glasgow.’ – James

‘To change people’s minds at the local level. All around the world, people want to change the climate crisis. But a year from now, I guess, first of all, on a local level, we want as many people as we can to join our movement; to know and to educate themselves and to realise that it’s real. And second, is to get our team bigger and bigger. One year from now, I hope our movement will grow to a bigger movement, to bigger projects and to stop climate change.’ – Meruyert

‘I really hope to grow the Bay Area team too. Right now, it’s just a team of two people, so having that help would be great. But, on a local level I think there needs to be more education, especially for the younger generation. Our goal with the Climate Clock on a local level is to educate those people and bring awareness to these issues. In a larger sense, the corporations and companies that I talked about earlier, just helping them, pushing them, towards a more sustainable future is […] one of our main priorities.’ – Kim

Credits

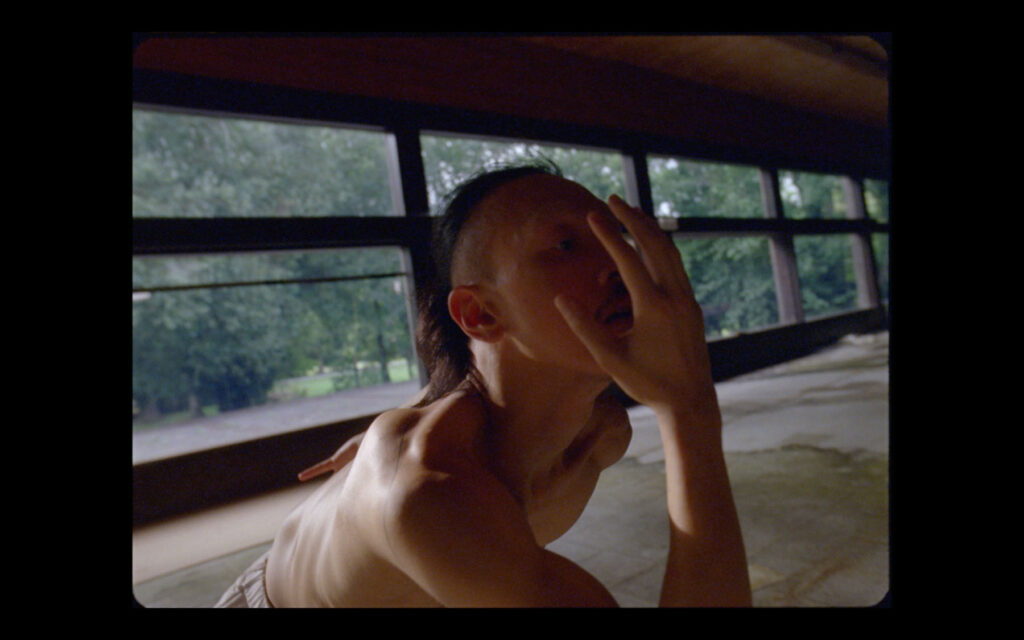

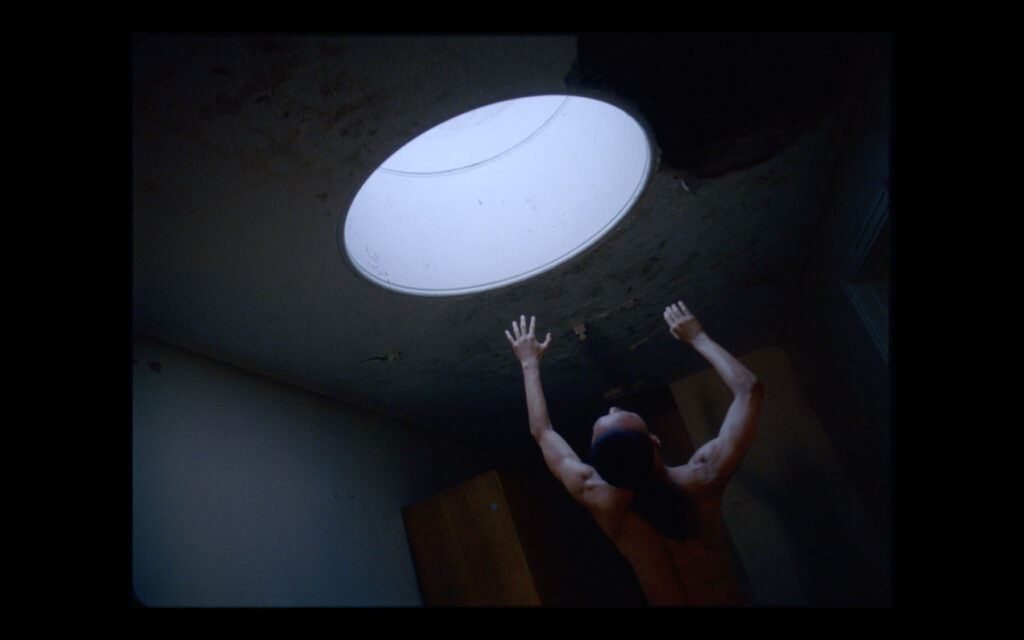

Images · THE CLIMATE CLOCK

https://climateclock.world/