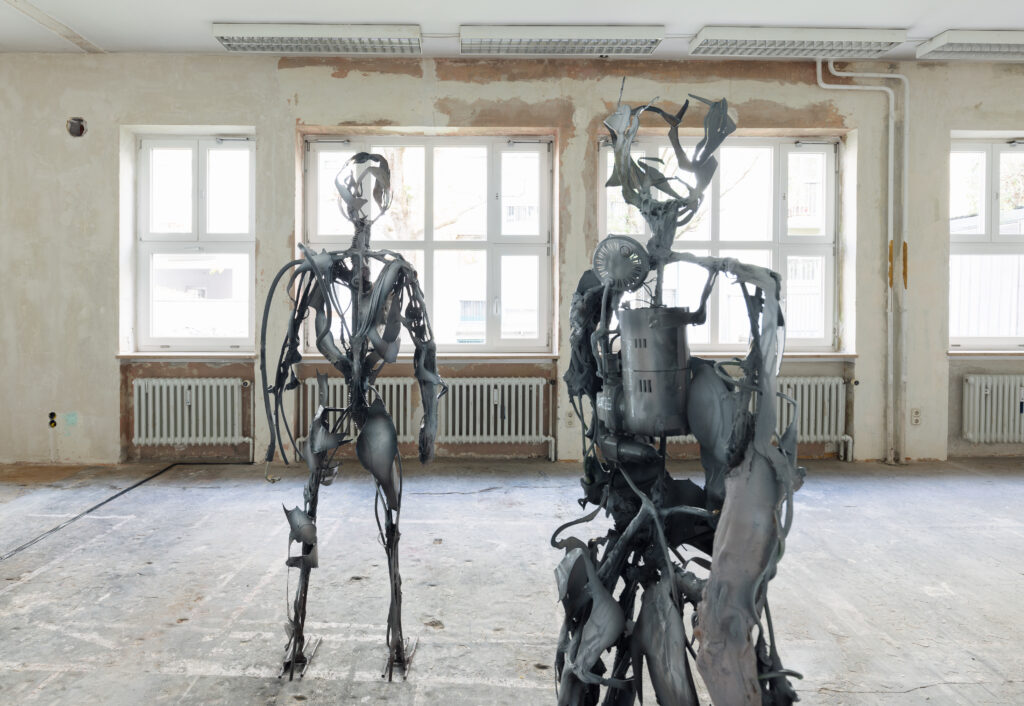

Lee’s biomechanical forms

After completing her Bachelor of Fine Arts in Seoul, South Korean-born artist Yein Lee went to the Academy of Fine Art in Vienna, Austria. She stayed there to live, refining her technical prowess into an intensely profound body of work. And she is far from done.

Combining her past experience, dexterous innovations and interest in advancing technology, Lee has exhibited her work in numerous locations, showing her work ten times just in the last year. Her sculptures have approached the world with the strength of a cyborg. Their creator has constantly developed alongside them, her mind evolving with the same creative mental software that transforms these objects into personable, breathing beings.

Her work has an unrelenting originality. The sculptures are crafted into augmented forces. Lee approaches the overall composition with creativity in mind; she creates the presented proportions, and her treatment of the fabricated flesh can be felt through panels and poles. Lee installs biomechanical forms that brush against the fabric of a wall. The dark, drooping and dagger-sharp bodies poke out of the white walls of a gallery. Xylophoned rib cages jerk out with splayed bones, like arachnid arms reaching around a polymer and epoxy heart. Loose limbs fall like sinuous vines bleeding black and stretching into nothingness like the electrical wires that they are. These forms are obscure and anything but human. However, they hint at a humanity that can be found within ourselves, only with multiple jabbering mouths sealed in polymer paralysis. If humans are contorted in hate and loosened by drink, Lee’s hand-made creatures are intensified with the cold glitter of a PVC plexiglass and wires that twist like wilted willows.

These are not merely artworks in stasis. They transform over time and have a life of their own. Lee transfers the essence of being into objects with an actuality and reality at their core, giving the pulsations of a creature with a soul.

You originally studied traditional painting in Seoul and then moved to Vienna. Since finishing up at The Academy of Fine Art, you have continued to live there. It has been almost a decade since you graduated from University in Seoul. Why did you stay?

I had no idea about the city at all. Soon, I decided there was a young, active scene going on, and there were many spaces for artists to produce, especially considering the smaller scale of the city. Many artists were around the city, and everyone was working around me, and I enjoyed this input and movement. Now I really have a sense of community here.

Did this sense of belonging come immediately or over time?

My friends are here, my partner is here and my studio is here. I now know how to source my materials, and I know how it works here when it comes to running my studio. This usually takes some time. You have to get used to a German-speaking country and then deal with the art bubble (which is all in English).

Your material practice has branched out from the norm and has spread into the realms of technological components, metals and alloys, and plastics and organic materials. At what point did you move towards sculpture?

Through my BA in Seoul, I focused on Asian painting, and then for my Masters, I followed a more modern path with Contemporary Art Direction. I went to Berlin and then went to Vienna for the Academy of Fine Arts, where I continued in the painting class. I struggled a bit as I couldn’t find my own visual language through paint. At the time, the whole Zombie Figuration discourse was going on (in the mid-2010s), and there was an overwhelming overload of paintings.

So, what did you do?

I tried to forget everything I had built so far, and I decided to leave Vienna and go to Shanghai for an Artist Residency Program. But I didn’t bring any material with me, on purpose. In the program, there was a lot of leftover material from the previous residents, so I just collected it all and began using these random materials that artists had left behind. Leaving my old studio behind and starting with new tools was really helpful. I started using hot-glue guns, plastics, acrylic colours and polyurethane. I started working with these new materials, and after that, my painting became more sculptural. When I returned to Vienna, I kept experimenting with different materials and processes, and learning casting and welding helped me get closer to what I was looking for.

The scale of your artwork varies, yet the forms depicted remain relatable. One can see a drill-motor heart and limbs of steel, a chest with spread combs like fork prongs and body positions that feel so human. When you returned to Vienna, how did you start collecting the materials for your sculptures? Are there human elements you search for which operate as surrogate body parts for the forms?

I like that it feels human. In 2018, I really started getting into sculpture. I turned to casting and melding metals out of curiosity, but soon I fell in love with it. After using these plastics and metals for painting, I began making the frames for the works, which later became structures in themselves. As I explored these forms of matter, I knew I needed an anchor to communicate with the viewer, as my visual language of monstrosity tends to be less communicative and more framed. Using the human form was a translator. There has always been a presence of organic matter in my work. Even before I went to Shanghai, I had always used bodily elements; when I returned, I deepened my research on organic structures and was influenced by pop culture and movies. This all helped push out my creativity, and body machine parts started working as surrogates, but sometimes they just expanded on body parts.

Technical skill is a quality by which sculpture is evaluated. Does your practice involve meticulous working and reworking until you are happy with the result?

Every time I work, there are millions of possible next steps to creating the sculpture. For example, how much should I bend this piece of metal? But I like that. It is nice to explore these possibilities and refine the options for finality.

«Finding what’s ‘right’ is a thrilling feeling.»

And how do you know when to stop?

I could pretend to be a genius and say, ‘I just know’, but there are rules to follow for basic forms; I have an individual formula, focusing on the completeness, content, consistency of form and ratio of texture to balance in the composition. When everything fits into what I want to talk about, I know it’s done. I’ve definitely grasped more of an understanding of finality, which came over time and through more experience with my materials. The experience gives me more choices in what I can do. The experience makes it easier to see what is possible.

«The point of arrival for artwork is the ability for the piece to be presented.»

However, for many artists with a strong technical focus, the mastery of a process can be overlooked for a purely aesthetic interpretation; it can become cold. Despite this, your pieces have a lucidity, a sense of being which can speak.

How do your technical skills allow you to grow such a concept?

Coming from a painting background, I came into sculpture with quite a messy and dirty technique, but I let it be like that, and it turned out that I liked doing it the ‘wrong way’. For instance, with latex, I was supposed to pour it carefully into the mould, but actually, I did it the wrong way to try something new. It gave me a more instant expression. At times, being used to traditional techniques makes the work enter a certain frame, whereas what I wanted to say about sculpture and how I wanted to expand my work was more fluid; let it drop and overflow. I thought, ok, let’s break some rules, see how far they can be broken and how I can use the pieces, whether they are ‘failures’ or not.

Do you wish for your sculptures to communicate with the audience somehow? Do you want them to breathe like us or remain objects for opinion?

I always have my own intentions and ideas about my sculptures. Sometimes I have favourite parts of a work and what it is supposed to be. However, once the sculpture is out of my studio and leaves my hands, it is not mine anymore. Sculpture should have its own agency, and it should be able to deliver certain things to different people but without the arrogance of a god. I like to leave it up to viewers with what they see. Sometimes it is very different, and I think, ‘that’s ok’.

How does it feel to separate yourself from them? And how do you feel about your work as a whole?

I feel strange. I do a lot of drawings, but they are not necessarily related to the outcome. Some parts of a drawing can be involved in this outcome, but the journey is only partially planned. Once I have finished a piece, I think, ‘what are you?’. Sometimes I feel alienated from the sculpture, and other times I feel attached to it. It’s a weird mixed feeling because I never planned to make this sort of work. After completing a sculpture and it is sitting in front of me, whether it is the scale or material elements, It still takes me by surprise.

They also possess a depth that seems personal. Rather than being shells or a disregarded snakeskin, they could almost be seen as extensions of your personality. Is your working method related to this emotional connection?

I make my sculpture in a way that fits my personality. My working method is who I am. I am always slightly rushing, determined and sometimes slightly clumsy and rough. But my character is shown throughout my work, and it’s funny to see it, but the gestures do show.

Are they autobiographical?

They express how I feel, but they aren’t autobiographical. Many artists take inspiration from their experiences, so some of my experiences are embedded into the process and final outcome. But then, for me, it often gets separated; the initial idea that exists when I start a work sometimes changes while I’m working as my thought process goes into a meshed structure rather than a linear method.

When you are in the process of making these artworks, what do you feel and see? What sort of environment do you put yourself in (besides the physical surroundings of a studio)?

Not too often, but sometimes I get into a trance. It feels like a buzzy, feverish and floating sensation when I really concentrate, but that could also be the caffeine and exhaustion. When I get highly focused and concentrate so much, I get absorbed into the process so much that my body disappears and it is just my brain and hands.

How do you want people to react to these works? The sculptures are hardly embodiments of peace and harmony. At least in the conventional, Edenic sense. Sci-fi characteristics emerge when words like ‘hybridism’ and ‘cyborg’ are thrown around. Still, your work takes a step further by removing the past and melding present silhouettes into alien forms articulated to a raw framework you have created. How do you react to sci-fi labelling and labelling in general?

Hybridity has been such a significant term that has circulated, but it is now a natural concept at this point. With sci-fi, the concept is a current metaphor for our imagination and society. It is a present-term idea that moves around our dreams and narratives. There are many bodies today that are very attached to artificial material, and I see the hybrid concept as a phenomenon that already exists. I was always more into manga and animation, so I got more ideas from these magazines than from traditional sci-fi; I didn’t grow up with it, but lately, I’ve been watching all the classics, but only as an adult. My works are about what I see and observe, but people can receive them as one ‘type’ of art. It is the same with science fiction: it gets categorized as one thing. The artist Ivan Pérard says, ‘Sci-fi’ is a modern fable’, which I very much agree with. Animism and mythology operate around nature and culture, and science fiction mirrors society just as much. It is about our life as it stands now.

And what do you want to change this attitude?

It is essential to keep talking about art in a way that doesn’t limit terminology and simplifies the language that describes it. In my work, there are lots of languages of monstrosity, and people immediately think of the artist, H.R. Giger and how many monster-esque forms are coming back in art.

«The sculptures embrace distinct ambivalent emotions.»

For me, the works are in a status of becoming. I want people to discover hope in the form of reflection on our current society. It is necessary to focus on the details and have more sub-categories to be aware of.

Do you think your work promotes that concept?

I hope so. I have been trying to find a way to communicate it with metamorphic presences, blending the ‘me’ and ‘you’ and ‘us’. For that reason, I worked more into the human form to express a language of monstrosity that is less misunderstood and more anchored. Making these forms relatable makes them beings you can communicate with. Components resembling human body parts communicated and specified what I wanted to say.

These sculptures have their own weight. They possess a dense mass that stands perfectly. They support themselves just like Francis Bacon’s creatures in his Crucifixion paintings did. There are various rods and stabilising factors involved. However, these prodding protrusions make the artwork whole by grounding the body and creating a proportionate form. How do you want your work to stand?

Through wires and steel supporting the sculpture’s weight, they can look weightless and rooted to the ground at the same time. Being in the air is a nonhuman thing, and my works take components of human anatomy beyond bodily function. I want them to stand with natural and artificial elements growing from this body coexisting.

And towards what environment do you see them moving?

I want to explore all sorts of locations. I don’t just want my work in white cubes. I’m working on this sculpture park exhibition in the Netherlands which will be interesting; the surroundings there are radically different, which will also dramatically affect how the sculpture behaves and how it is interpreted.

Your production has led to your works avoiding the limbo between weightless futility and a heavy, immobile mound. In many senses, the fact that these works float yet are still weighed down by gravity makes them appear as embryonic creatures captured in stasis. Do your choices in materials and proportion impact the presentation/display of your works and their ultimate impact on audiences?

Proportion is only one part of the decision-making on form, so it’s hard to say it’s the ultimate effect, but it is crucial that my works have a certain openness. With Devouring Chaos (2022), I liked having a balance between the human anatomy, electrical wires and wooden branches that poke out of the skins. The branches make the piece float in the air and, at the same time, stay rooted to the floor as if it were a plant. I like having a duality and coexistence of weight and weightlessness, a growing and wilting being. I find that concept really interesting, and I want to explore it further in a different direction.

A word that sparks to mind when observing your work is protuberance. Not only in the content of your subject matter, (as it juts out of a human shadow with the suddenness of a razor-sharp guillotine) but the context of these protrusions. Do you want your artwork to jut out from the norm?

«I want them not just to jut out of the norm but to stretch out the norm and expand normativity. These forms convey that we are all simultaneously different and alike; it is the form that decides the content just as much as the content decides the form.»

How do you decide what form these sculptures will ultimately take?

In the beginning, the size of the works themselves is planned. Because of shipping, the scale is regulated for practicality. When I started working on my latest pieces, I fixed their average size first. However, the forms then develop and grow out of my imagination, and with Devouring Chaos, I got the idea of this fazing face and legs frozen in motion from a long exposure picture. Showing constant movement across frames in a particular image was an interesting visual element that led to a transition in the movement process.

Your expertise in gleaning used and disregarded materials comments on the extremes of consumerism and assists in communicating the issues regarding the state of the environment today. How do you see your art playing a part in the way we move forward?

I would like to embody specific thoughts and concepts in my sculpture. They are metaphors and suggestions. Let’s say a viewer could see a broken iPhone cable as part of my work and wonder, ‘Yeah, I do have a couple of broken smartphone cables somewhere at my home, too’ Then it’s a good start.

And the ultimate goal for them?

Being born abroad and living in a foreign country is frustrating, and you sometimes feel like you do not belong. Even the concept of nationality is weird for me here, and within Vienna, I live in a bubble where I only speak English. It is weird but interesting. I want to explore the possibilities of representing the body in this way. For example, the issues of hyper-consumerism and the ecological crisis come up in my sculpture with aesthetics and materials providing belonging in an extended body. I want to embrace more possibilities of the body. I am not just ‘me’, but I am a human. I consist of thousands of cells, fluids, and microorganisms living with me. This comes out in the work with not only the mechanical components and broken machines, but also branches and formed figures that look like microorganisms and then faces. I try to use macroscopic with microscopic imagery to comment on both the body as an individual entity and the world as a whole.

There’s no missing one of your works. Not only do they jump out with their presence, but they are wholly yours and could be produced by no other artist but you. The structures you make are transformed into a veritable presence that catches the eye in a second. Is there more to be done?

I want to keep creating and working on my career. The practice I want to promote is one where humans are not in the centre of the world, but I want my sculpture to coexist with the world in a way that expands certain areas of thought but not in a ‘core’ social sense. I am happy with what I have been able to make, and I try to give credit to myself instead of just being a perfectionist and asking myself every time, what more should I have done? But sometimes, you just can’t push it further because of budget, time or energy.

Are you confident in the artwork you produce?

There is always room for improvement, but the best thing is to be able to learn from your work and improve upon it the next time. Looking back, I did my best work within a limited time, and although it is difficult, I always want to improve. However, I am happy with what I have done and what I will continue to do. Sometimes you have to move on and keep working on the next piece.

«My confidence is in my desire to explore more possibilities.»

Credits

- Yein Lee & Nour Jaouda, Installation view 2022, Paulina Caspari, Munich. Photography by Thomas Splett

- Detail, devouring chaos – growth of reconstructed time, overflowing bodies, and static electricity. Photography: Courtesy of the artists and Loggia, Munich/Vienna

- Yein Lee & Nour Jaouda, Installation view 2022, Paulina Caspari, Munich. Photography by Thomas Splett

- Yein Lee & Nour Jaouda, Installation view 2022, Paulina Caspari, Munich. Photography by Thomas Splett