“I think the energy of being in a place that you’ve never been in before can make your brain think in different ways”

Kevin Parker’s shoot for NR Magazine came merely a few days before Los Angeles was locked down in response to the coronavirus pandemic that has, slowly but surely, turned everything we know on its head. ‘It was great to do something normal, something that I have been doing a lot of in the last few months; doing photoshoots and having fun,’ Kevin explains – now back in his native Perth, WA. ‘It took the attention away from everything that was going on. It was nice to spend three hours, just doing a photoshoot with wicked clothes.’ As the force behind the powerhouse band Tame Impala, Kevin is confident that the band has the resources it needs to weather the blow that the pandemic will have on the music industry; people still listen to his music online, ‘apparently’. When it comes to making music, it’s a well-known fact that Kevin works alone – so in that sense, business continues as usual. Yet, like many other artists who have had to abandon plans for the foreseeable future, the release of Tame Impala’s fourth album, The Slow Rush, in February has been overshadowed by this unprecedented upheaval. The band were due to play a number of shows in the US and Mexico in March, with an Australian tour following in April. ‘We’d spent so long preparing for the tour, and were at this absolute crescendo of getting ready for the shows – and as soon as we had played the first show, it was like, ‘Oh my God, what’s going to happen? For now, the dates have been postponed – which undoubtedly comes as a blow to the Tame Impala fans who have been waiting five years for a new album (though a number of fans turned to punning The Slow Rush’s exploration of ‘time’ in response to Kevin’s announcements of the postponed shows on social media; ‘it’s a slow rush’.) In its entirety, The Slow Rush is an infectiously funky record – and the influence of 70s disco and the current mainstream that has welcomed Kevin into its arms, are clear. Much of the heavy fuzz and reverb found on earlier Tame Impala albums have been slickened and given a shiny polish. Looking into the past may preoccupy some of Kevin’s lyrical reflections on the album, but there’s no reason for why Tame Impala’s sound shouldn’t move forward. It’s somewhat bittersweet that an album that unpicks the strangeness of time should come at a moment when, across the planet, we will have more time to contemplate the past and the future. It’s a heavy weight to place upon the shoulders of The Slow Rush, and if there was any kind of global crisis that was on Kevin’s mind at the time of writing the album, it would have been the climate crisis. Tame Impala partnered with Reverb, an organisation that works with artists to counterbalance the carbon emissions that are created through touring – something Kevin explains as a ‘no brainer’. Touring, especially on the level that the band are, has a huge carbon footprint, and trying to restructure the way world tours have been done for years would be a daunting task for Tame Impala to undertake themselves. But, it’s Tame Impala’s responsibility ‘first and foremost’ to ensure that the band is setting the right example, especially for a band that performs to thousands of people at every show (though, he hopes, the people that listen to Tame Impala are ‘probably not the kind of people going around denying climate change.’) During our Skype call, I ask Kevin about the prerequisites for listening to music; he says he has come to realise that his appreciation of music is shaped by ‘not necessarily the space, but who I was with when I heard it first, or what I was feeling.’ There’s a ‘helplessness’ to this reality; a ‘lack of control, from the songwriter’s point of view’ over how their music will be received. No doubt, Kevin could not have anticipated that The Slow Rush would come at the time it did; all that’s left to do now is listen to the album in solitude and await the moment when the music world comes back to life.

NR Magazine: The Slow Rush was a long time in the making – how do you feel listening to it now that it’s out there? Is it a relief to be done?

Kevin Parker: Absolutely, yeah. It’s funny because the moment I’m finished with the album, and the moment it comes out, I expect this huge sense of relief and a weight off my shoulders , but it never comes. That might just be because I have trouble appreciating things once they’re done; on release day, I didn’t get to enjoy it because I just can’t enjoy these things. I still enjoy the album, but it’s not always easy to enjoy the music when you’re aware of so many other people listening to it for the first time, and invariably judging it. When I look back, I remember thinking to myself, ‘Shit, am I ever going to finish this?’ Now, I am able to appreciate being on the other side of that. I was listening to the album yesterday; if I’m ever on Spotify for whatever reason, I’ll probably slowly make my way to the album and give it a listen – just to see what it sounds like now after a month. (It only came out a month ago, that’s crazy; it feels like a life time ago!)

What were your reasons for making an album that explores the concept of time?

It’s always been something that fascinates me – not time itself as a weird existential force – but the way it affects us. The way you can smell something, you know, if you walk past someone in the street who’s wearing cologne that someone that you were in a relationship with ten years ago was wearing, and you haven’t smelled it since then, it just sends you into an absolute time warp. The way these experiences shape our lives intrigues me. At the same time, I didn’t consciously go about making songs about all these things but, when it comes to an album, the kind of music that I’m making subconsciously informs what I start singing about. Like, when I made Lonerism, the chords and instruments I was using reminded me of times when I felt alone growing up, and so the album ended up being like that. And I feel like The Slow Rush is the same kind of thing, where the music I was making – the rhythms and cords – just made me think about the future, the past and everything in between.

I listened to Innerspeaker again a couple of weeks ago and it transported me back almost ten years back which was, like you say, an emotional time warp. Does the way you listen to your music change with the passage of time, or is the sentiment the same?

Definitely not, no! It’s funny you know, you’re saying about Innerspeaker – it’s the same for me. I hardly ever listen to the album the whole way through, but if I really pay attention to parts of it, it’s crazy because it so clearly reminds me of where I was and what I was feeling. Like for you, it’s kind of crazy; music is crazy how it can do that. I guess the other thing is, listening to Innerspeaker now, it feels like it was someone else. I just hear this naïve kid, not really knowing what he was doing, which is nice because I don’t judge it anymore. I don’t judge it in the way that I do with The Slow Rush. Innerspeaker was so long ago that any of the mistakes, any of the things that are wrong with it, just sound charming and cute, which feels weird to say…

I guess you’re so disconnected from it, with that amount of time passing?

Yeah totally. That’s also good because it finally allows me to listen to it like someone else, not as me – the person who made it. That’s kind of the dream, to be able to listen to your own work. I don’t know how much money I would pay to be able to listen to the songs I’m working on at the time, you know? To be able to listen to the album, as an outsider… I’d give anything to be able to do that, but it’s something that only time can offer.

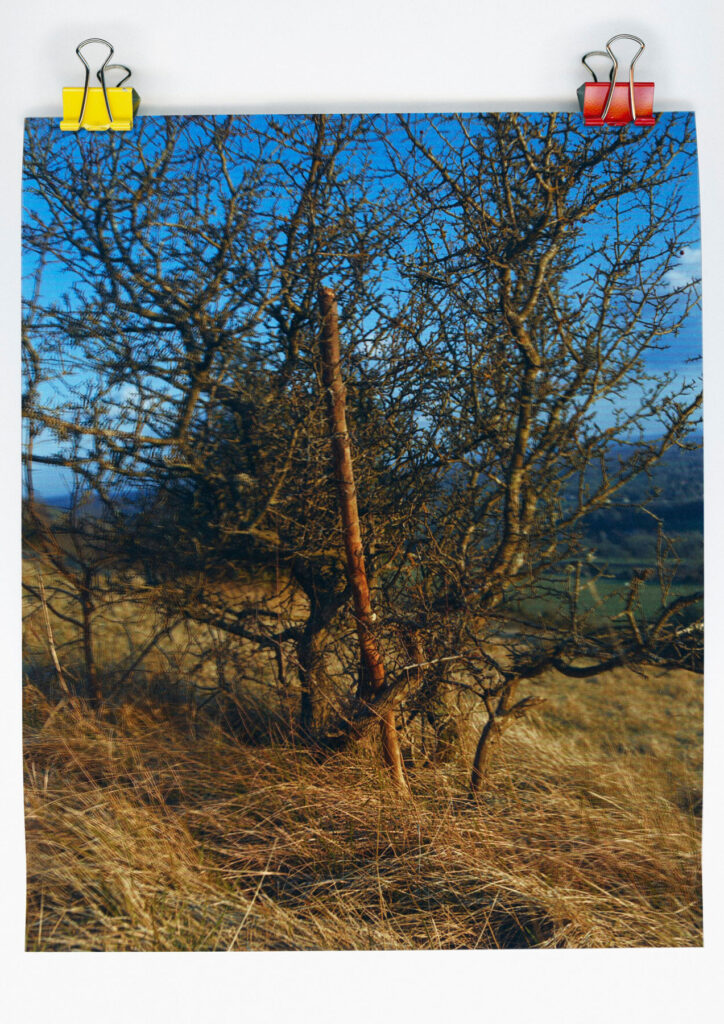

I’ve seen a few people mention that the cover for The Slow Rush was 3D-animated, but it’s a photograph from Kolmanskop, Namibia, right?

Yeah – I’m not going to lie, I was a little bit disappointed when people asked how I synthesised the image. I was like, ‘Man, I flew half way across the world to take that picture!’

I can see why people don’t believe it’s real. How did you decide on using that as the album cover?

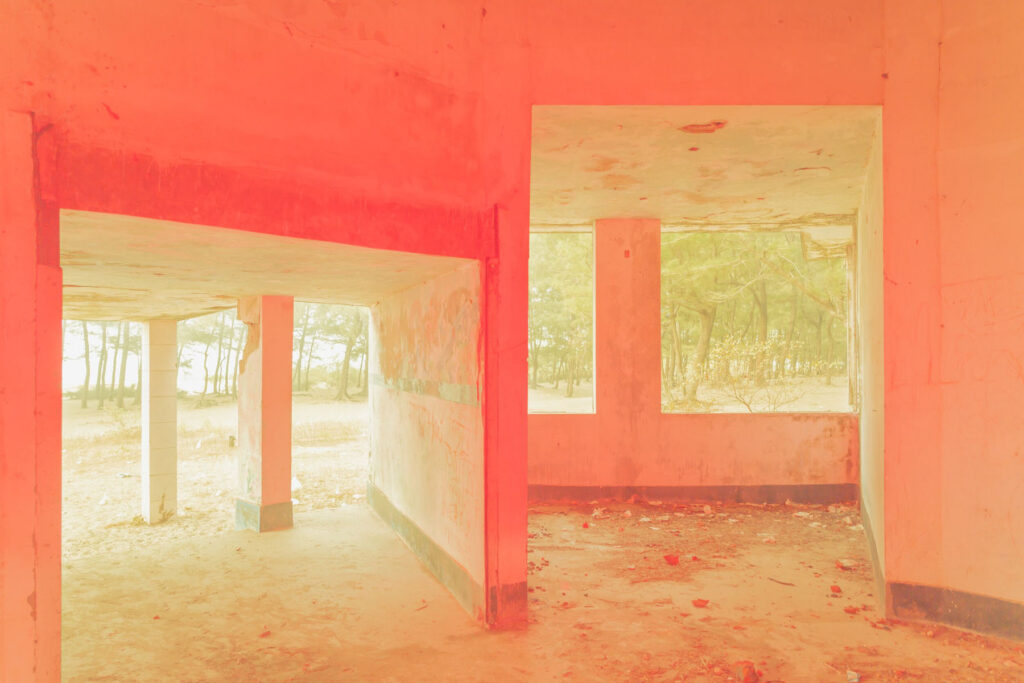

I was a little bit obsessed with abandoned places for a while, and the internet is full of pictures of these abandoned ghost towns; there’s just something so enthralling about them. I mean, probably not coincidentally, it’s like the experience of time passing smacking you in the face. I guess some people find it depressing to look at, but I just see such beauty in it. As soon as I saw that place, I knew that we had to go there. Kolmanskop is like a ghost town in the desert and it’s super windy, so sand just builds up in these amazing ways. What I love about it, is that it looks like liquid – and if you look at a picture, you can’t tell if it took the sand that’s up to the window a matter of minutes or decades to reach that point, you know? You can’t tell which it is and that’s kind of what I love about it.

You’ve previously spoken a lot about how you make music, but how important is the space around you during that process?

It’s important – not that I need to be in a particular place to make music, but I think there’s something about being somewhere new. I think the energy of being in a place that you’ve never been in before can make your brain think in different ways. So, with The Slow Rush, I tried to milk that. I was renting Airbnbs, taking music equipment with me and recording there for a week on my own. There’s this nervous tension about being in someone else’s house…

Though I guess, you got more than what you bargained for when you were staying in Malibu [when the worst wildfire season in California in 2018 ravaged the area]?

Well exactly, yeah. And I’d only been there for one night, and the next morning I just had to go. I had stayed there for a week earlier that month recording, and it’s funny because I think about that space – I started a few songs off this album there, and when I listen to something I think about where I was when I working on it. It takes me a while to realise that that space doesn’t exist anymore; it was completely burned to the ground, it was just rubble. When I listen to a song, or the chorus of a song I wrote there, I remember the colour of the walls; what the door looked like; what it was like leaning out into the backyard. It’s kind of weird to think it just doesn’t exist anymore because, in terms of memory, we never think of a space as not existing, you know? Our minds think of the space we’re in as these permanent places, not something that can just disappear in one day.

It goes without saying that Tame Impala has seen an unprecedented level of success in the past ten years – what’s next for Tame Impala and for you?

That’s a good question; I don’t know. Well, I want to get making music. One of the things I was looking forward to so much with finishing this album was it just being done with. There was so much stuff that I wanted to do, in terms of Tame Impala and not; there were things that I couldn’t do until I made this album. So now, I’m happy to be on the other side of it so I can do the things that seemed wrong before. I have no shortage of things that I want to do now. I’m kind of excited about it – whatever that ends up being.

Credits

Creative Direction · NIMA HABIBZADEH and JADE REMOVILLE

Photo · JJ GEIGER photo assistant AMANI BATURA

Fashion · SHAOJUN CHEN

Grooming · ALEXA HERNANDEZ

Interview · ELLIE BROWN

Special Thanks · Grand Stand HQ