“The relationship with physical forces has an eloquent capacity that can be very big; it has the kind of expression that is universal.”

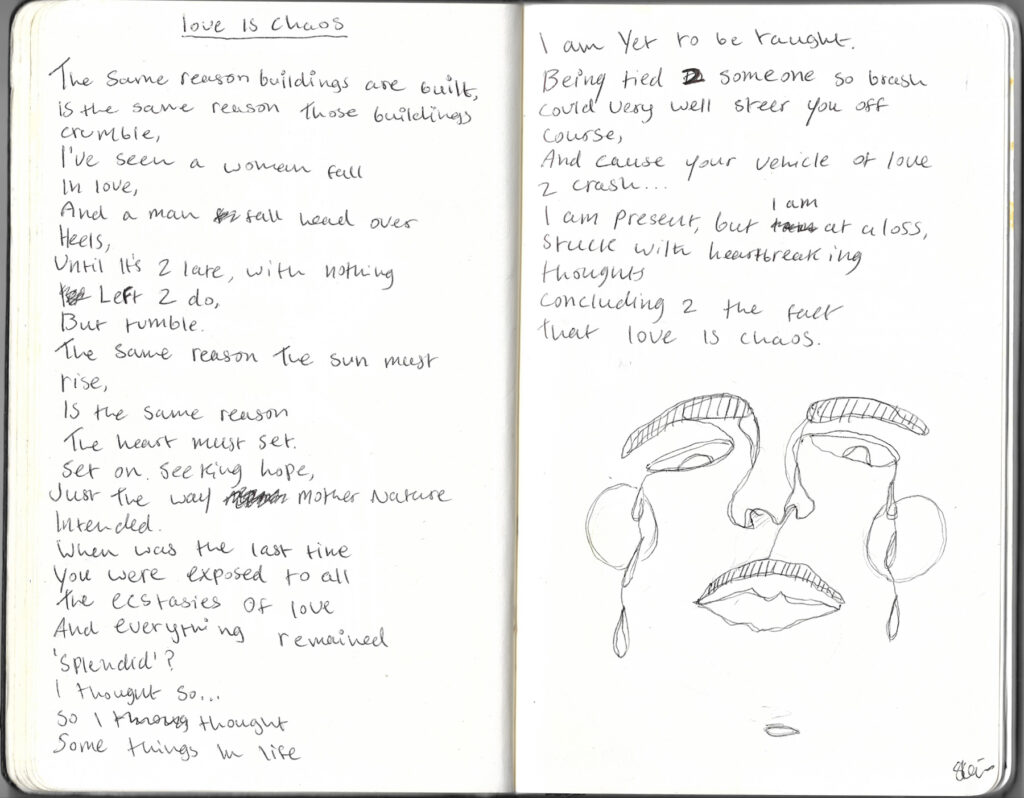

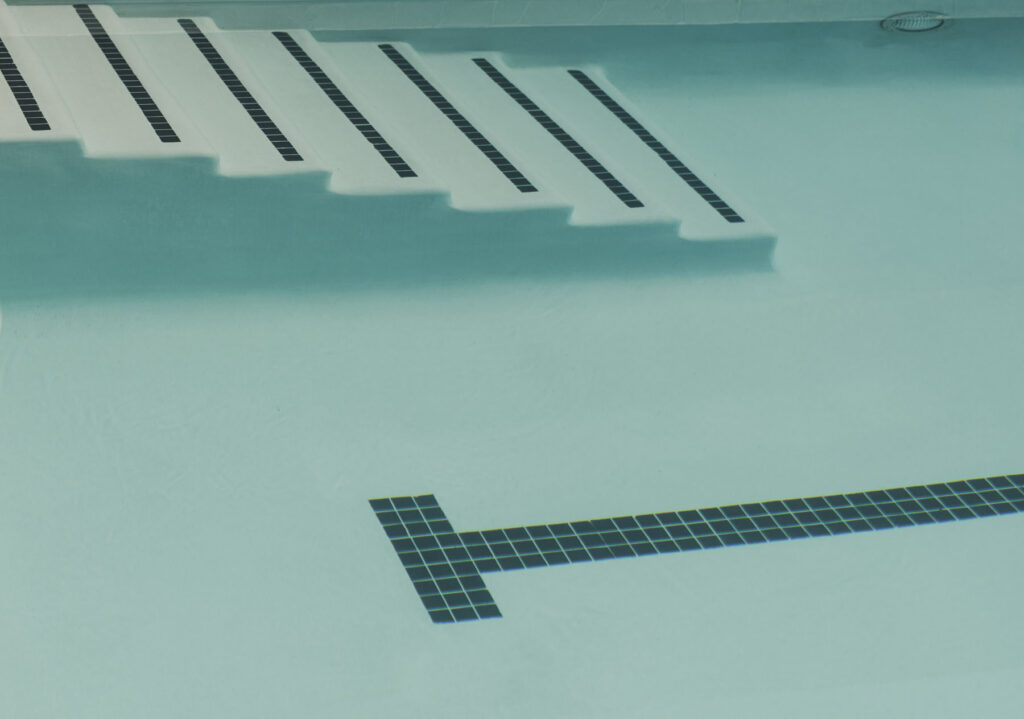

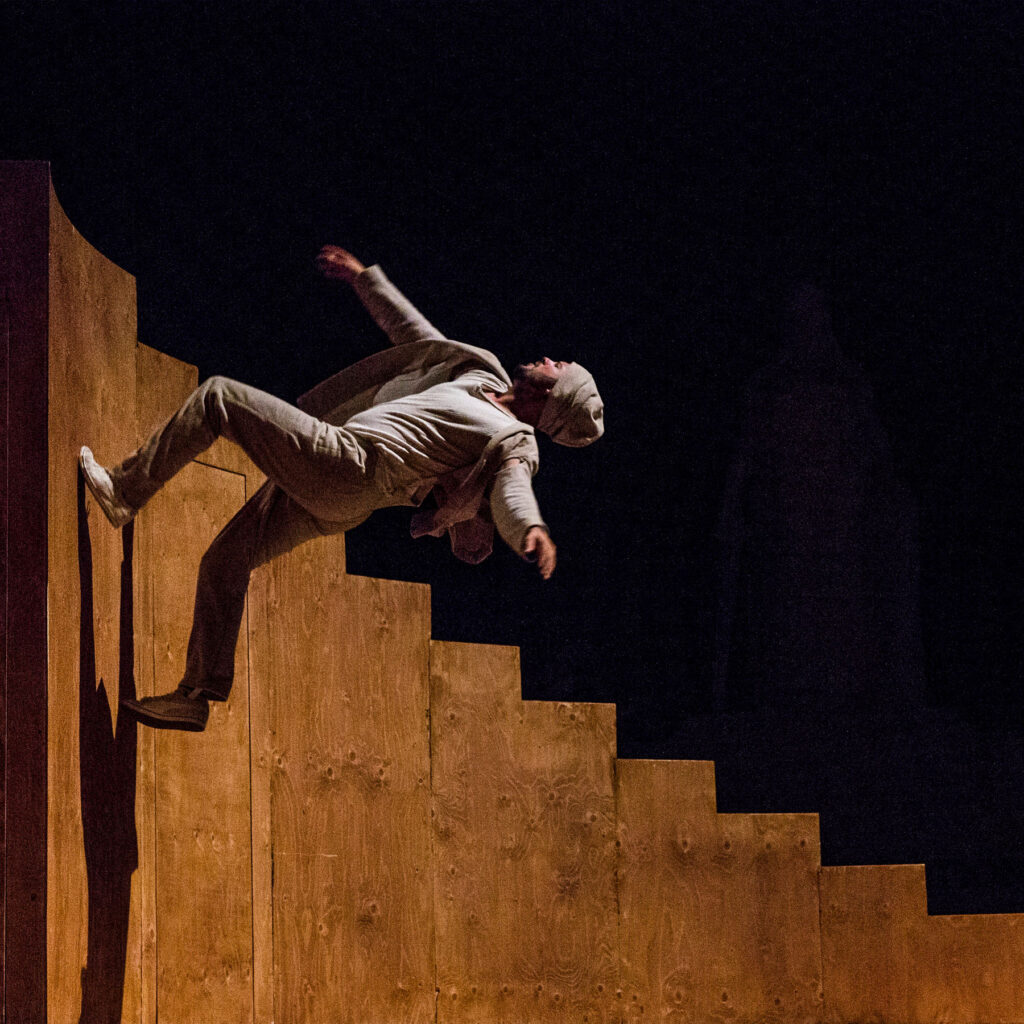

Online footage of performances choreographed by Yoann Bourgeois, such as the 2014 piece, Celui qui Tombe, can be disorientating to watch. Six performers navigate a suspended platform which moves and tilts at varying, and at times, uncompromising, angles. At first, the six are disengaged from one another but, as they become increasingly restricted in their movements, begin to interact as a group. At moments, members of the group fracture off, only to realise that they cannot go it alone; at one point, the six appear increasingly discombobulated as Frank Sinatra’s My Way plays eerily in the distance. Celui qui Tombe becomes, like many of Bourgeois’ performances, the universe – society as a whole – in a microcosm. There is something quite fantastical about Bourgeois’ work, as is the case in La mécanique de l’Histoire, an instalment at the Panthéon in Paris in the Autumn of 2017 – the third edition of the annual ‘Monuments en mouvement’ event organised by the Centre des Monuments Nationaux. Within the interior of the Panthéon, a series of separate performances take place simultaneously; like the dancers in Celui qui Tombe, these performances are detached, but not unconnected. In front of François-Léon Sicard’s monument to The National Convention, four performers, clad in grey, climb a spiral staircase, each taking turns to fall off the steps onto a trampoline enclosed below within the rotating structure; which, in turn, springs the fallen performer back onto the staircase. Ad Infinitum.

Nothing is left to chance in Bourgeois’ work – not the choice of the four figures in grey who, from, from a certain angle, seem indistinguishable from Sicard’s figures, nor the precision of each movement. For Bourgeois, who was trained in circus art at the prestigious Centre national des arts du cirque, it is our relationship with time, space and the physical forces that is central to his practice. His performances unsettle the equilibrium and, often, induce a sense of vertigo, but it is through this process of exploring the constraints of the physical forces that our humanity is brought to the fore. Though it can be almost reassuringly soothing to watch as a figure repeatedly falls and rises on a rotating structure, it also brings to mind an endless stream of questions.

Namely, given the importance of site specificity in Bourgeois’ work, can watching footage of performances of La mécanique de l’Histoire come close to capturing the overall experience? The question of recording presents its own set of rules, Bourgeois believes, as different mediums present different possibilities; ‘I think, if we try to transfer living art into video, we will only be disappointed, but that goes both ways; things can appear in the video that aren’t possible to see in real life.’

How did you develop your practice?

It starts with where my practice came from, as a child who had this desire to never stop playing. There’s a moment when a child chooses a direction, as part of growing up, and that is a step that I never managed to take. Fortunately, I found the circus, which allowed me to remain undisciplined. Within circus, I realised that what really resonated with me was the relationship between physical forces. Of course, circus isn’t just about this but, personally, I wanted to be able to make closer contact with these forces. So, I worked with a team to build structures that would enable me to research the interactions that we have with the physical forces.

What is the relationship between the body of the performer and the structure of the set?

I would call it a device rather than a set; it’s through this device that the individual becomes a subject. The devices amplify specific physical phenomenon. In science, we’d call them models – they’re simplifications of our world that enable me to amplify one particular force at a time. So, the individuals, when they become the subject of these particular model worlds, they are able to engage with forces in a new context. Together, this ensemble of devices, this constellation of constructed devices, tentatively approaches the point of suspension. And so, this makes up a body of research; it’s a life’s research that doesn’t have an end in itself.

Is the space that surrounds a device important to the overall performance?

Yes it is; all the performances are site specific, so when I talk about ‘suspension’, that also involves the relationship that the device has with the environment. As such, the art work is poetically enhancing the environment, and vice versa; the environment is poetically enhancing the device. I’m looking for something that works both ways, and it’s also through this that I’m looking for the point of suspension.

La mécanique de l’Histoire, performed at the Panthéon in Paris, embodies that relationship between the device and the environment – would you be able to explain the concept behind that work?

So, it was following the same line of enquiry as global research into the point of suspension. The Panthéon is emblematic of our history, and so I wanted to make something that would be appropriate to that space. It’s a place that embodies the footprints of our history, a history that is both eventful and full of conflict. So I presented a series of devices which could be seen in 360 degrees; the audience could move around the devices because they were all placed in spaces that would allow for that circular movement. In the centre of the space, there was Foucault’s Pendulum, a device which, in the nineteenth century, provided tangible and visible proof that the earth turns. At the heart of this work was this fascination with movement.

What is the relationship between physics and performance?

The relationship with physical forces has an eloquent capacity that can be very big; it has the kind of expression that is universal. This is something I look for through my work, because the physical phenomenon is something that happens across cultures.

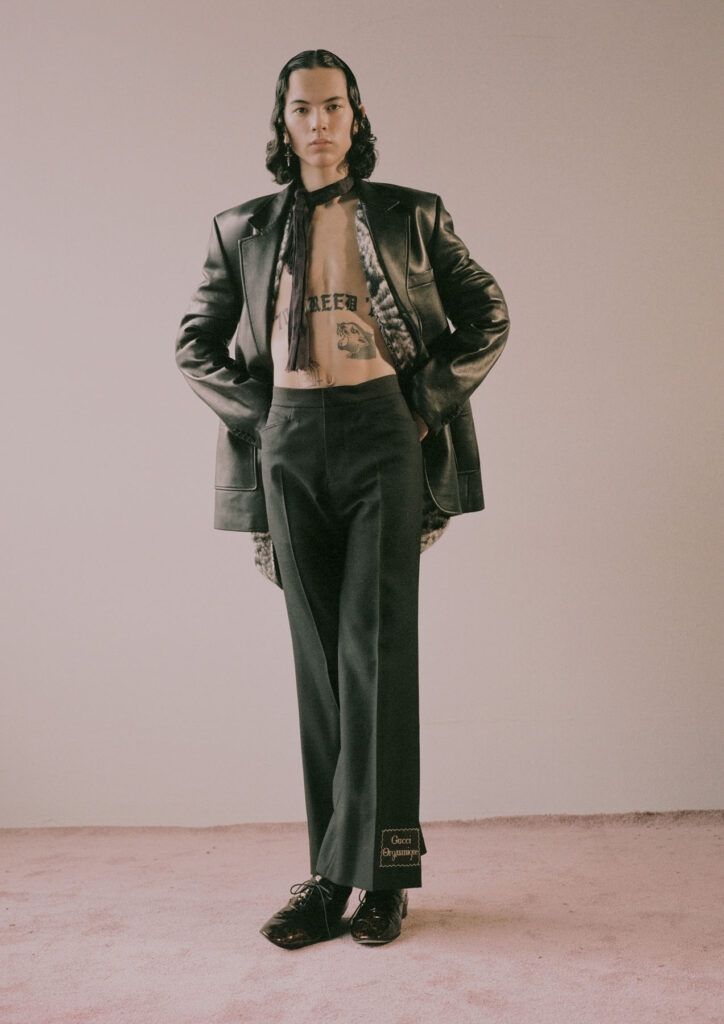

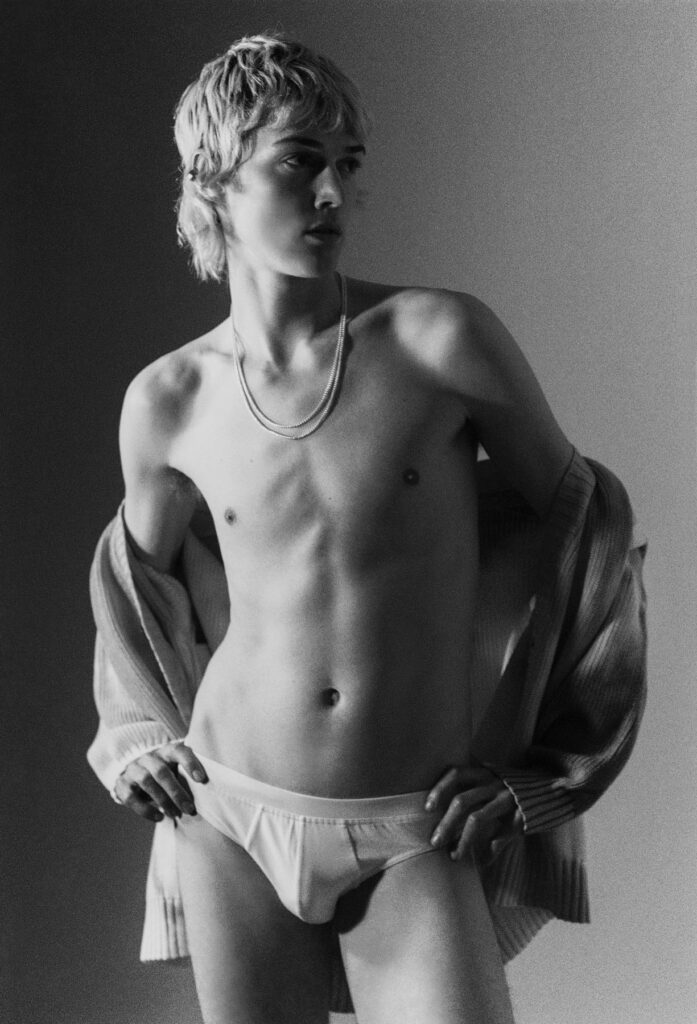

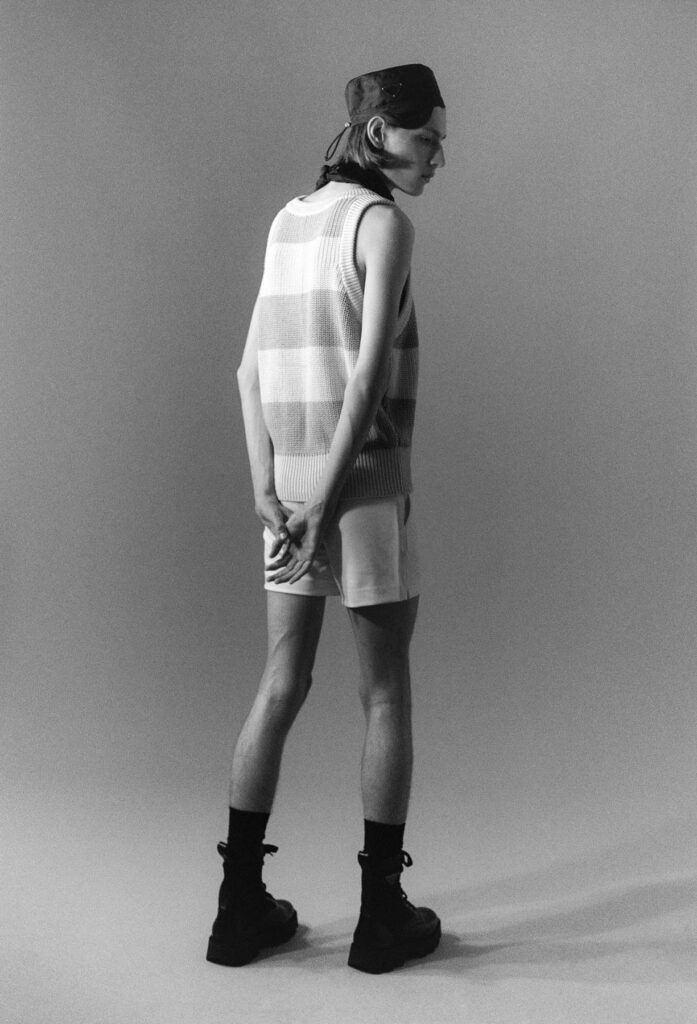

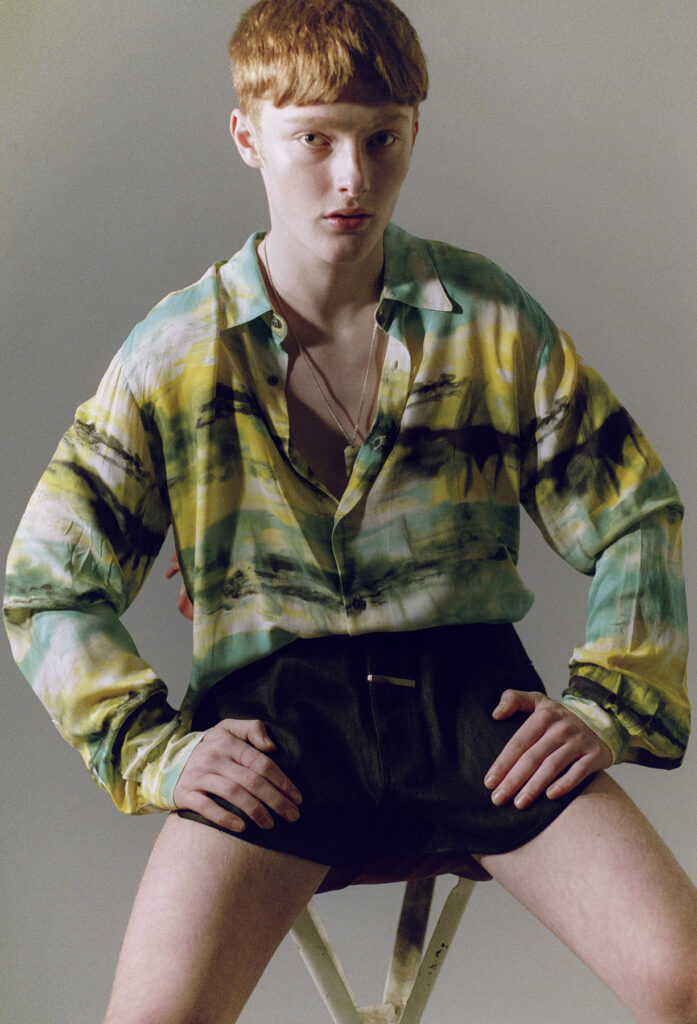

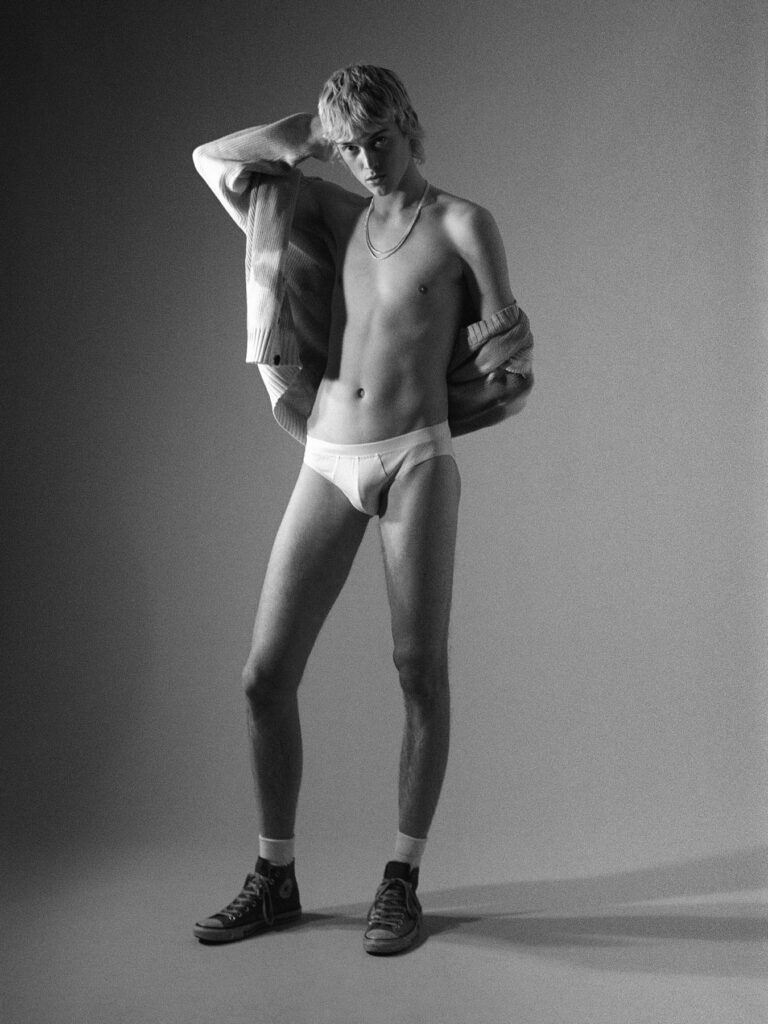

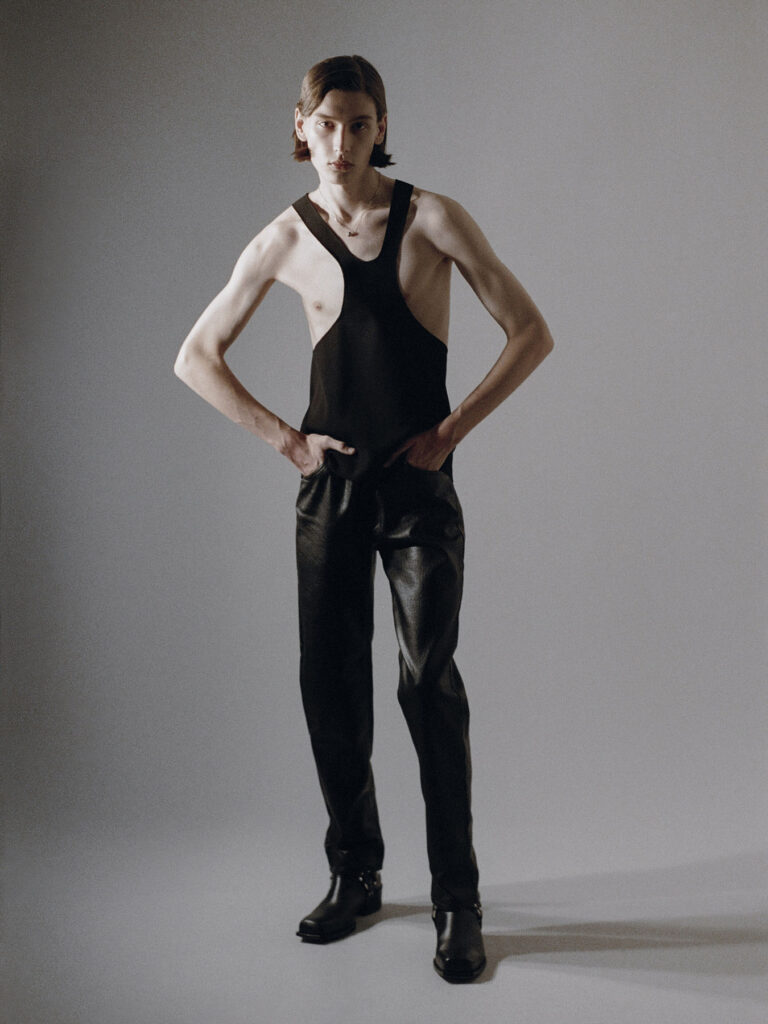

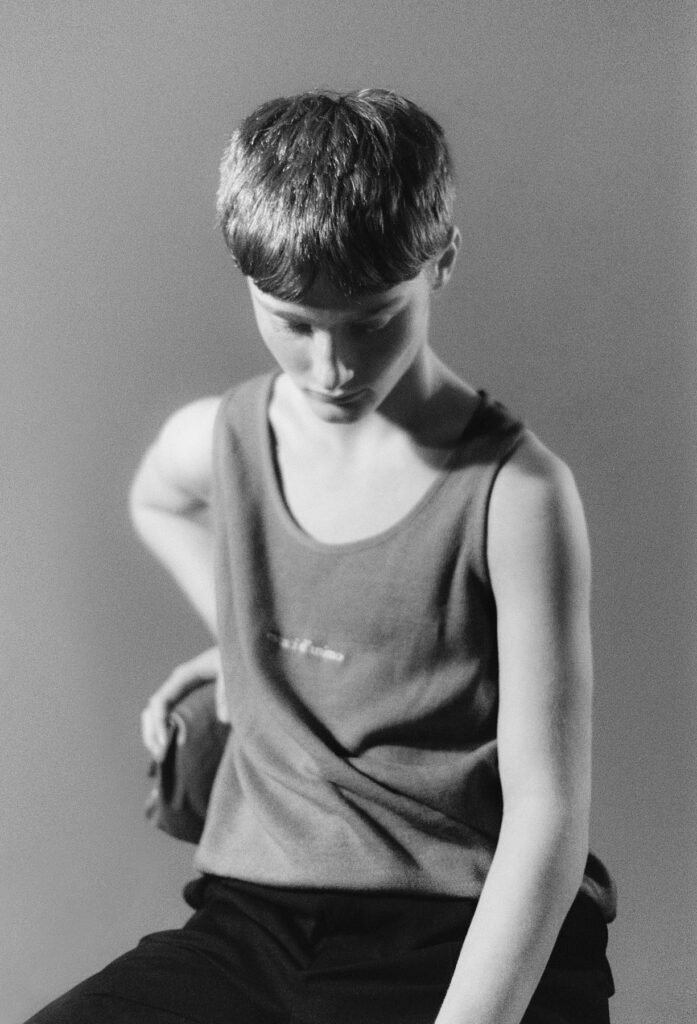

Are the costumes of performers important or secondary in a performance?

No, the costumes are actually quite important for exploring the relationship with the physical phenomenon. The costumes help to create something concrete. I’m trying to make our humanity visible, it’s not about being a specialist acrobat or a dancer. I’m playing with the most elementary gestures of our daily lives – like, just standing up, for example. The costumes work to enhance this elementary simplicity that I’m looking for.

How do you want viewers to engage with your work?

I think it links a bit to the previous question, in the sense that I’m trying to generate empathy from the audience. The essential question is one of relationships, I’m considering the idea that, as beings, we are about relationships. A performance is something that only exists through the relationships of the present; it exists only here and now. Something that is extremely important to me is seeing our relationship with the universe, in times of ecological catastrophes, looking at our relationship to the earth. And it’s here that the poets have their role to play.

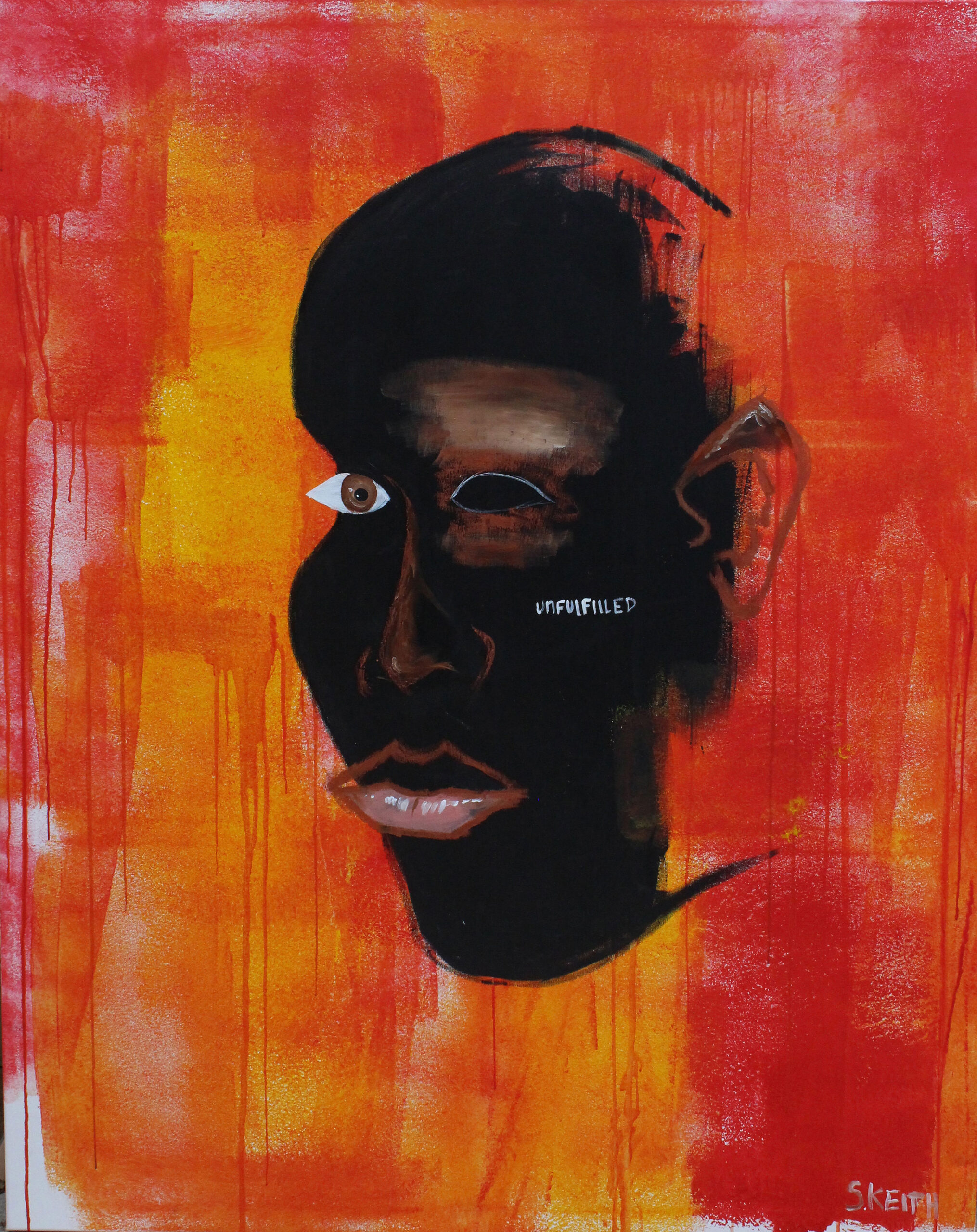

Credits

Photography GÉRALDINE ARESTEANU

www.instagram.com/yoann_bourgeois

www.instagram.com/celuiquitombe

Designers

- La mécanique de l’Histoire (All photos)