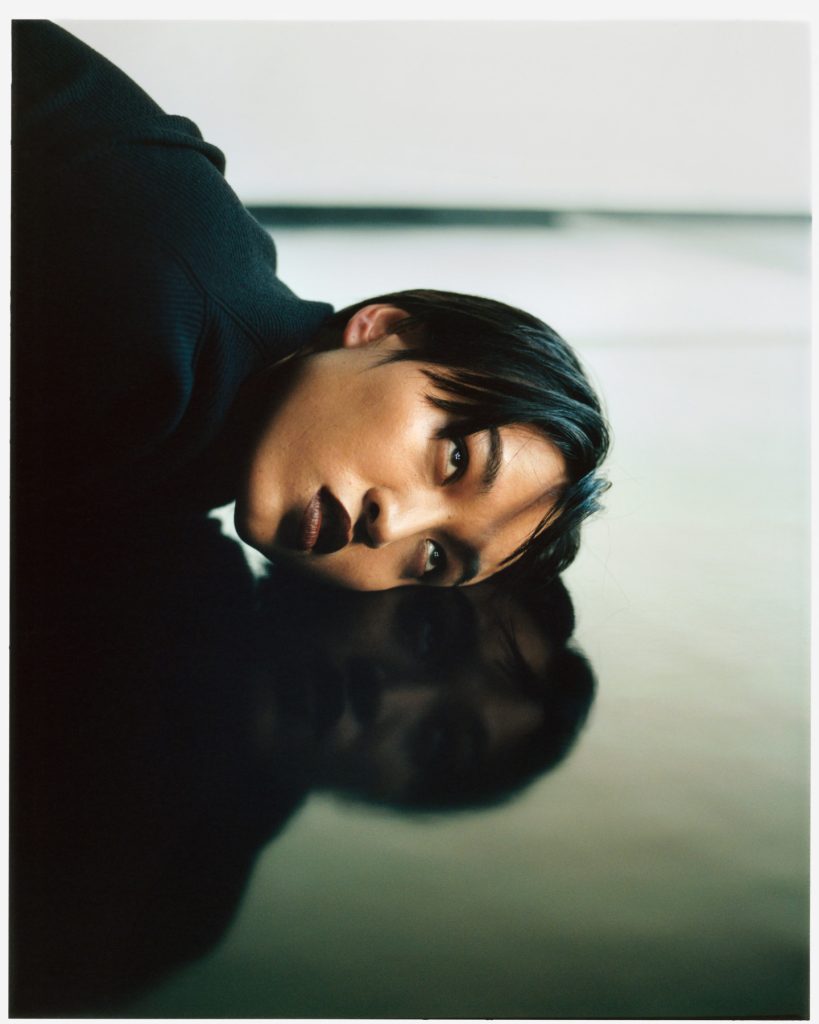

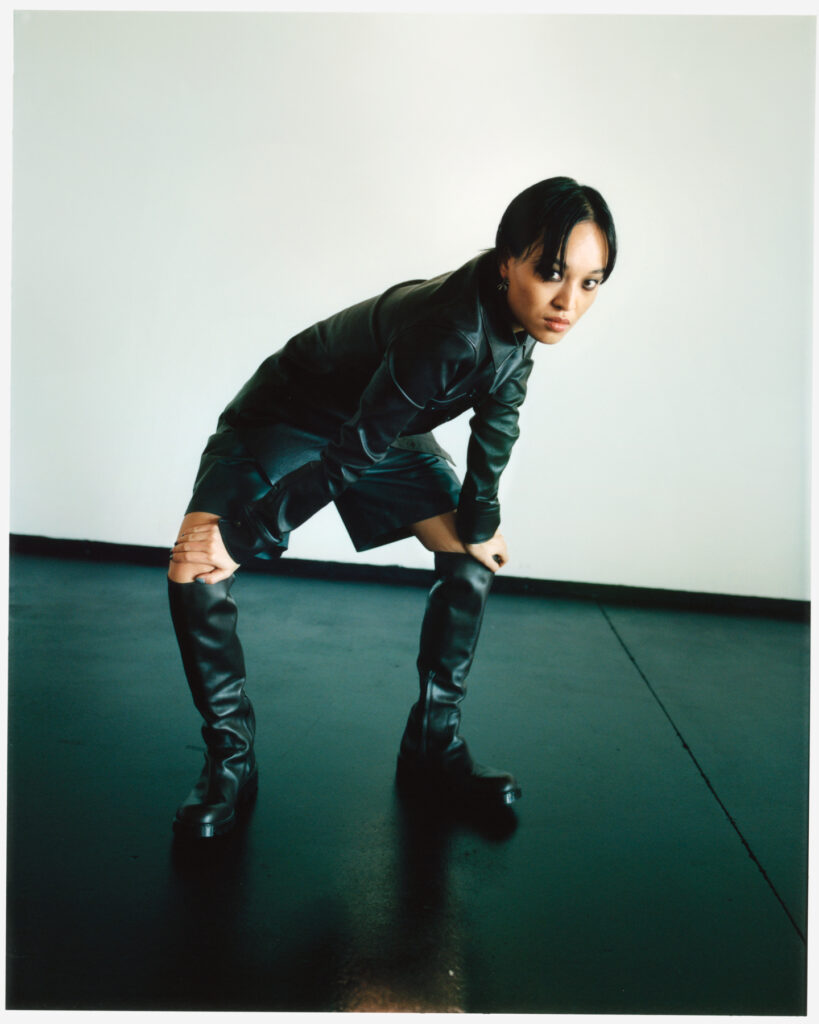

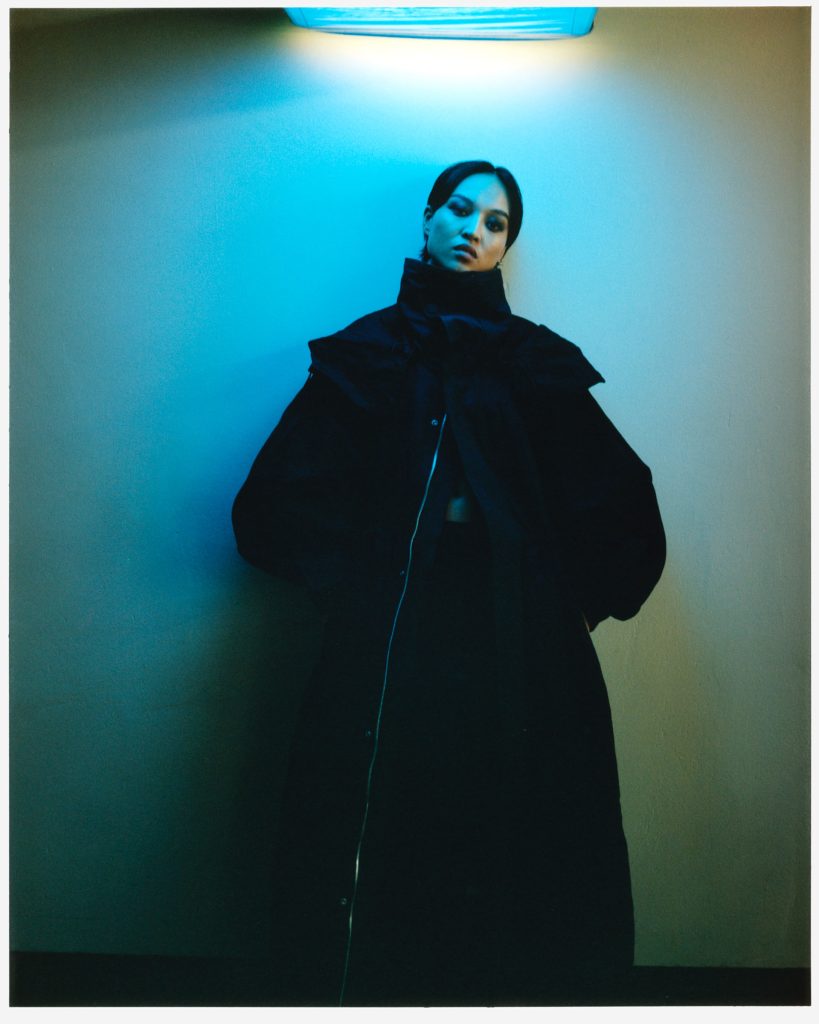

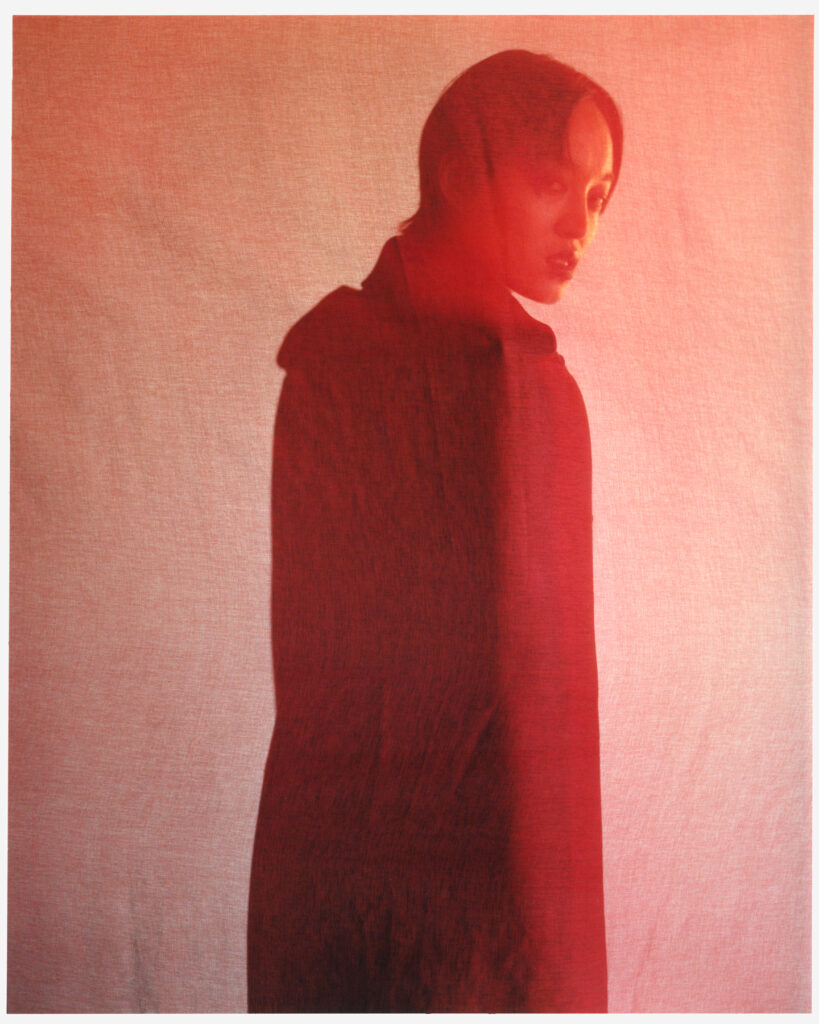

Pan Daijing is an artist and composer whose work defies easy categorisation. Earlier this year, Daijing released her third album, Tissues – an hour-long record taken from the artist’s performance piece of the same name that was shown at the Tate Modern back in 2019. The work was conceived as an opera in five acts, combining Daijing’s long-standing exploration of electronic music. In a Zoom call from Berlin where Daijing lives, the artist jokes that Tissues almost predicted the pandemic – not least because of its title, but also as a performance about hopelessness and a pervading sense of despair that seems to categorise the world we live in now. As an exploration of the operatic voice, Tissues is not immediately like Daijing’s earlier albums, 2021’s Jade and Lack (2017), which are more akin to noise music – with electronic sounds evoking the eery, isolating hum of an industrial landscape, interspersed with distinctively, sometimes uncomfortably, human guttural sounds.

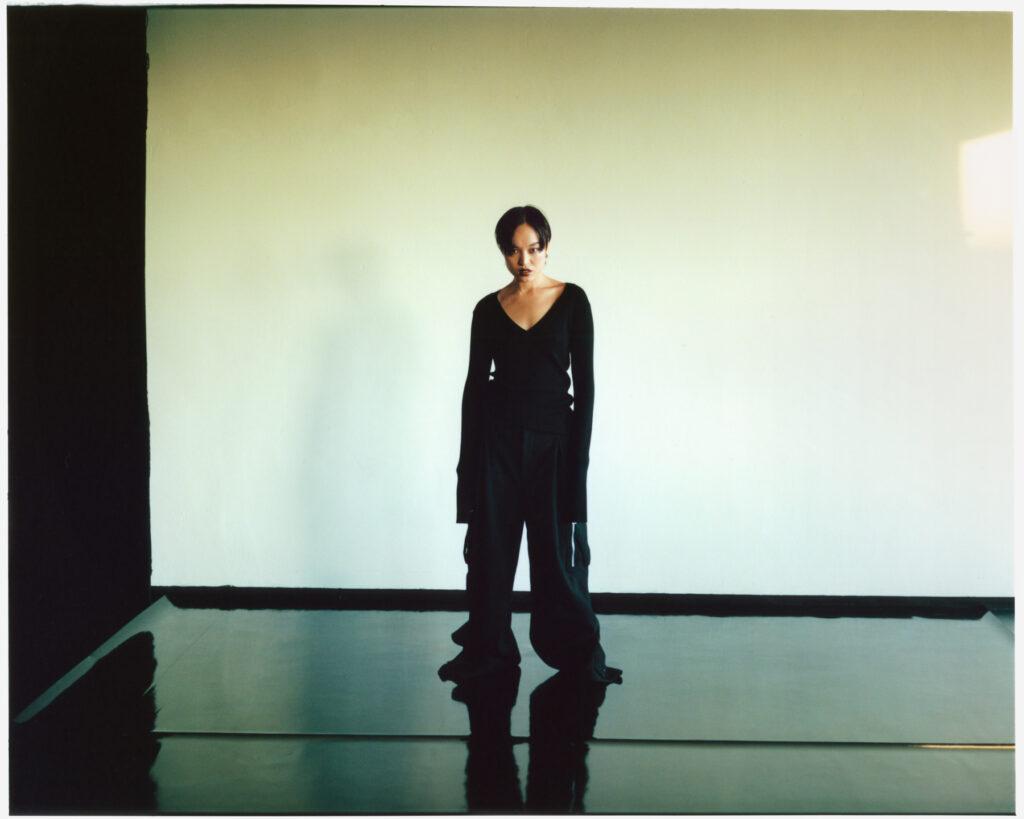

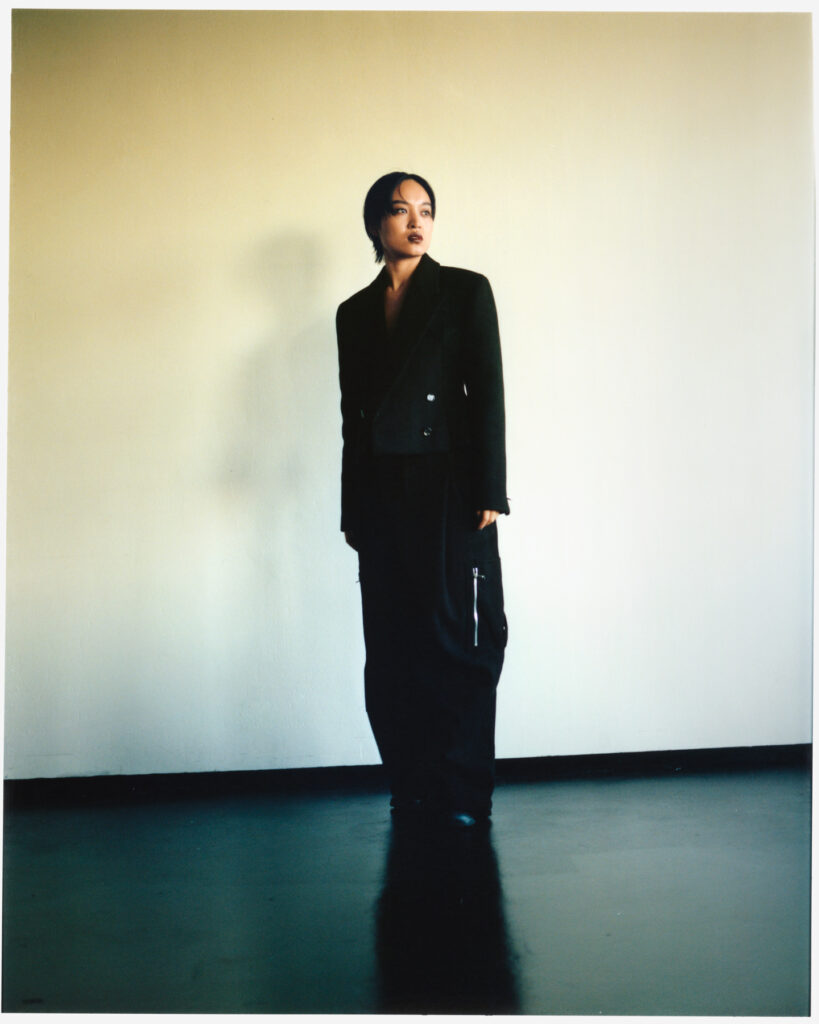

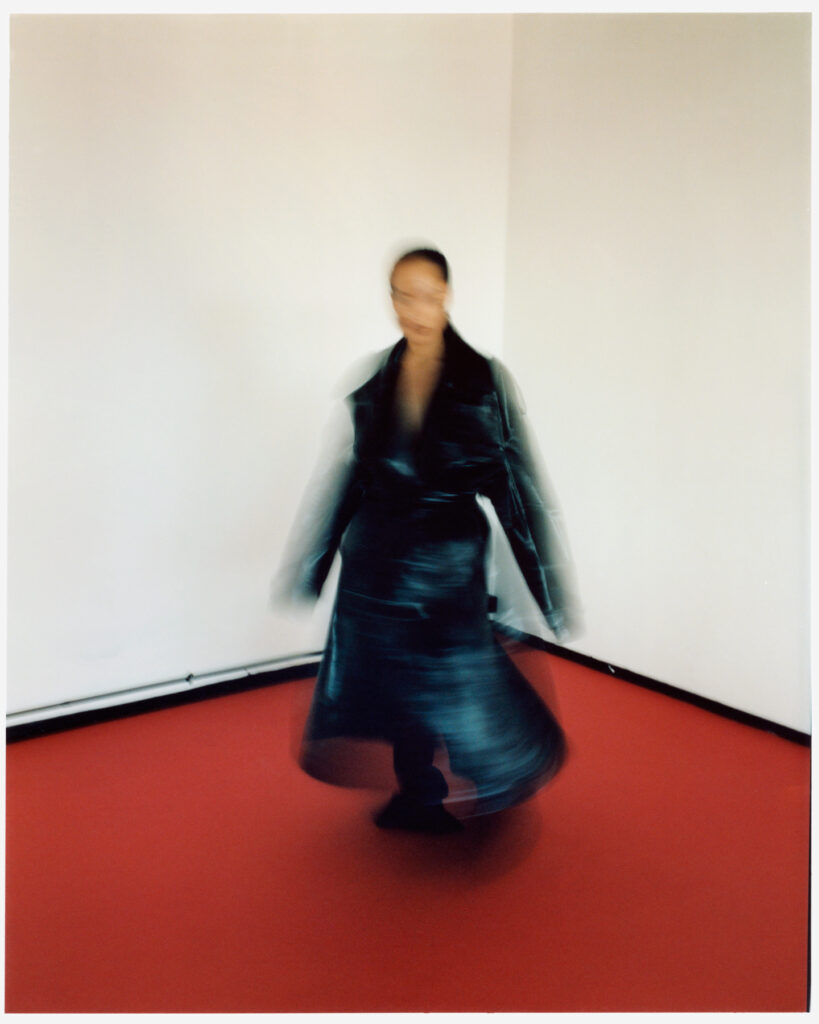

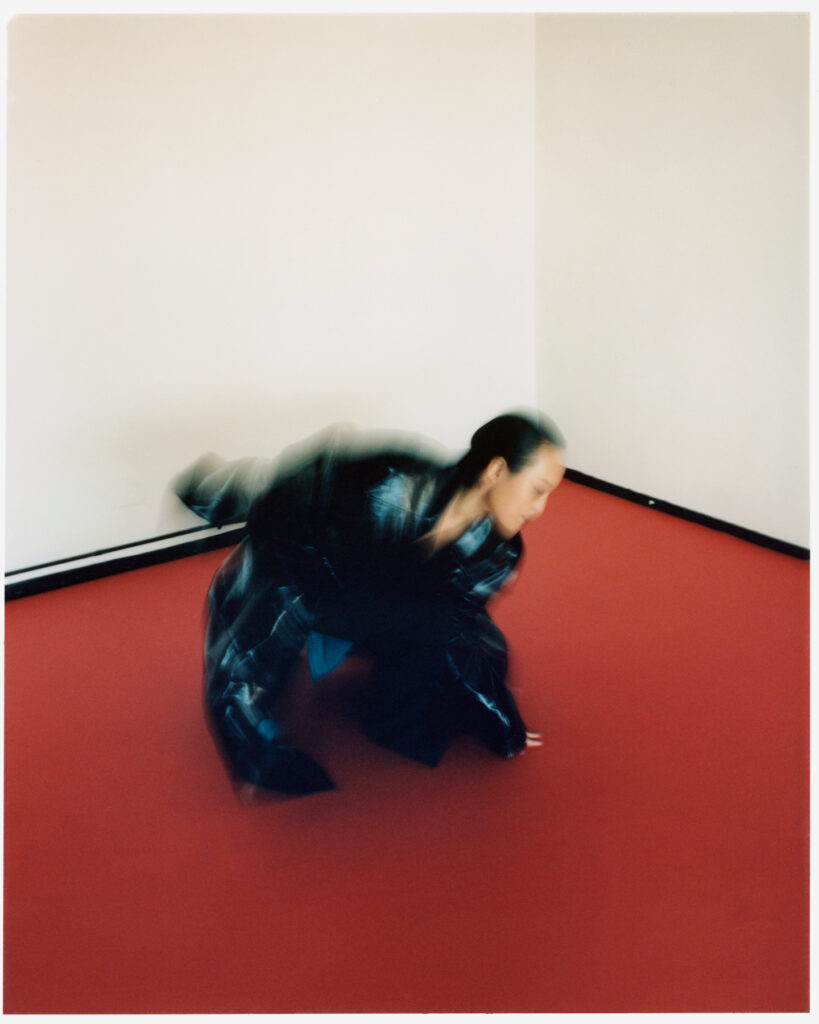

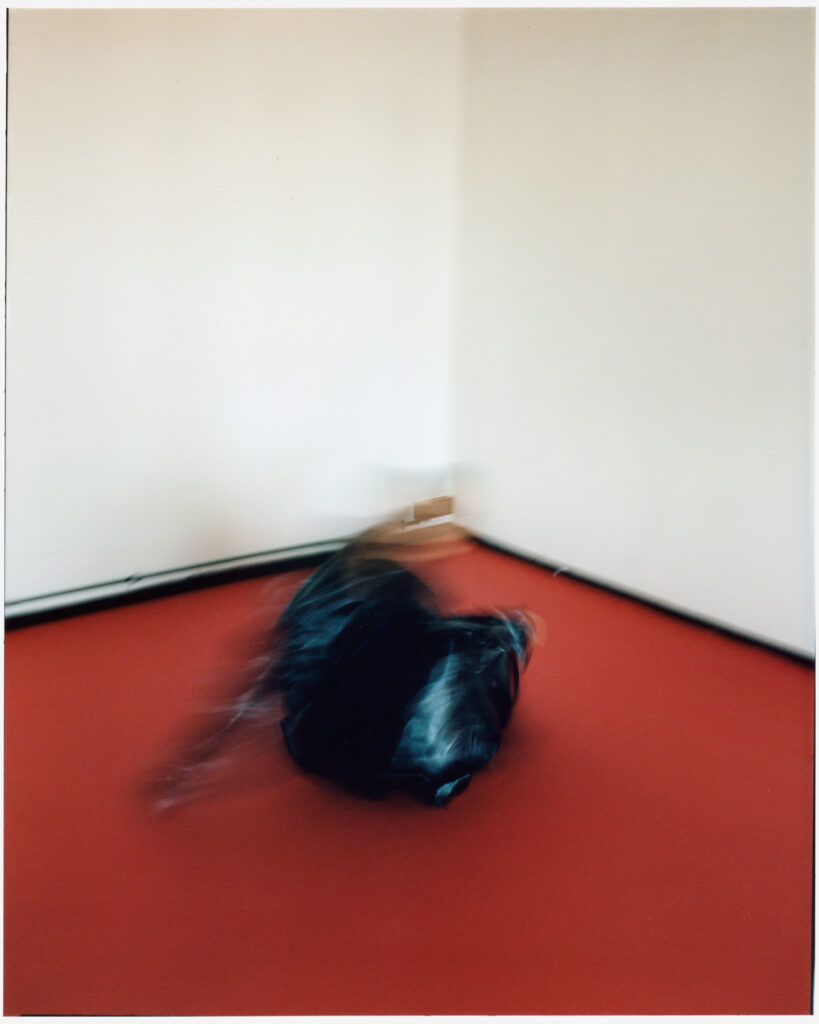

Daijing has performed, as a musician, at a string of Europe’s best festivals and at other venues, whilst also being commissioned, as an artist, to work with museums and art institutions – where sound and music remain central components within these pieces. Below, we discuss the boundaries of her work, drawing on the German composer Wagner’s notion of Gesamtkunstwerk, or the ‘total work of art’. It seems, to me, a term that aptly describes Daijing’s practice, without putting too much of a label on her, or her work. In fact, it is through music and art that Daijing aims to transcend categorisation in itself. By using music, sound, light, movement and design, Daijing creates work that explores a hybrid realm of what we often want to label as either ‘music’ or ‘art’, and thus allows the separate components to be interwoven and to communicate with one another.

Daijing describes a lifelong fascination with the human voice – as a child, she says, she would close her eyes and listen to someone’s voice, at school for example, and try to guess who was speaking. “It’s an interest I’ve always had,” Daijing explains, “and when you look for inspiration in life and in work, you always go to places that you’ve always felt fascinated by.” In essence, Daijing’s work is inextricably woven into the fabric of the space, the environment, the context, in which it is experienced – whether that is in a gallery setting, in a club, or alone – listening to her records in solitude.