WARP

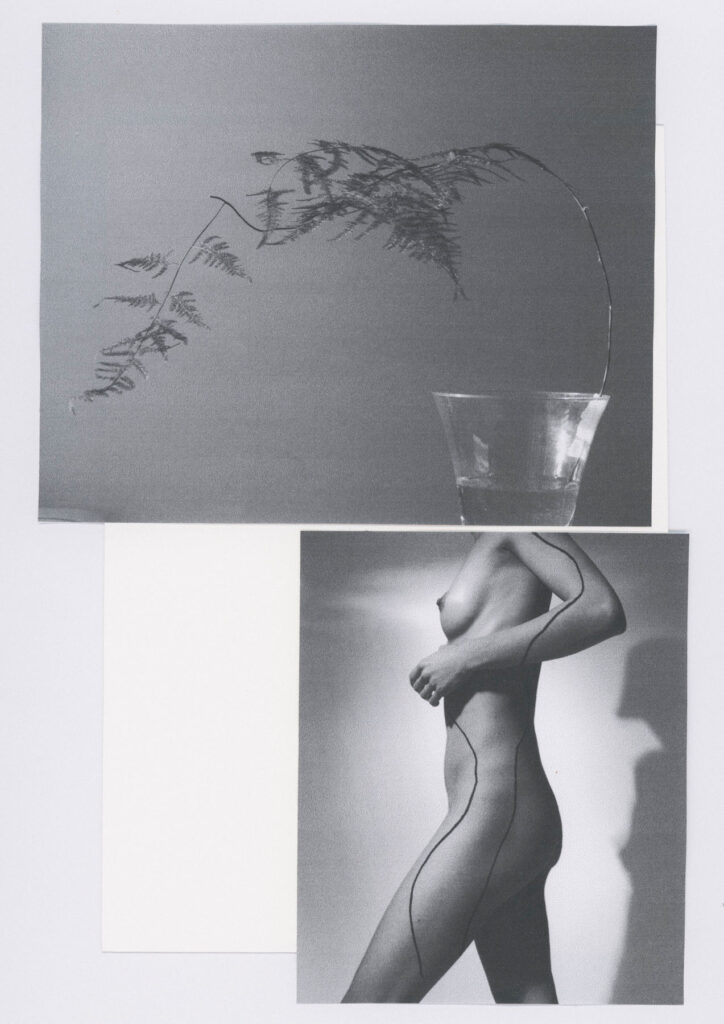

NR presents Soundsights, Track Etymology’s sister column: An inquiry into the convergence between sound, its visual expressions, investigating music’s intrinsically visual narrative quality.

Hello guys, thank you for being here, it must be pretty late now in Japan. How are you feeling about the upcoming release? It is your first LP since 2016! It’s been quite a journey! Global tours, several collaborations, a lot of experimentation. There is this restless component to your work, always evolving and shifting both sonically and conceptually. Is this record your way of crystallizing what you’ve been up to these last 8 years? What made you finally settle down?

Our music has always flirted with genre-bending, but for this record in particular, we aimed to incorporate various genres into our sound more than ever. Perhaps what has changed the most is that this time, we aimed to capture what we think is the essence of our live shows, rather than focusing on a specific sound, having toured a lot since the release of our previous album —Our main inspiration for this record stems from physicality and the ways our audience interacts in a live setting with our sound. Of course, Techno and Black Metal are still our two sonic compasses, but this time we drew from a wider plethora of music genres like hardcore, noise, and industrial. It is also the first record where we have a female lead vocalist, Zastar, the last member to join us!

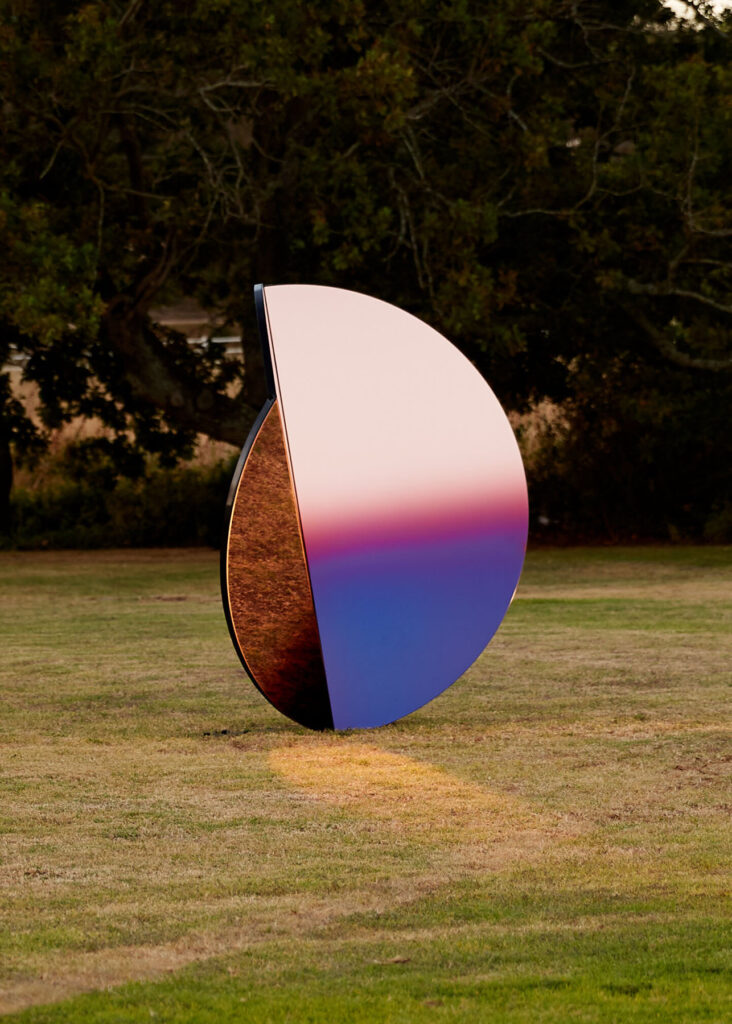

The experiential referentiality of your music is definitely felt in the new record, and its presence makes even more sense considering that you describe yourselves as a performance art collective. I was listening to Warp while watching the visuals Rafael Bicalho created for it, and I almost felt like I was in a 3.0 musical drama. There is a sort of lingering quality to it, those almost fading vocals mixed with the track’s physicality and the alternating moments of calm and soaring. It was as if I was listening to source music for a film. What was the concept behind it? Is it one act of a longer narrative that continues throughout the whole record?

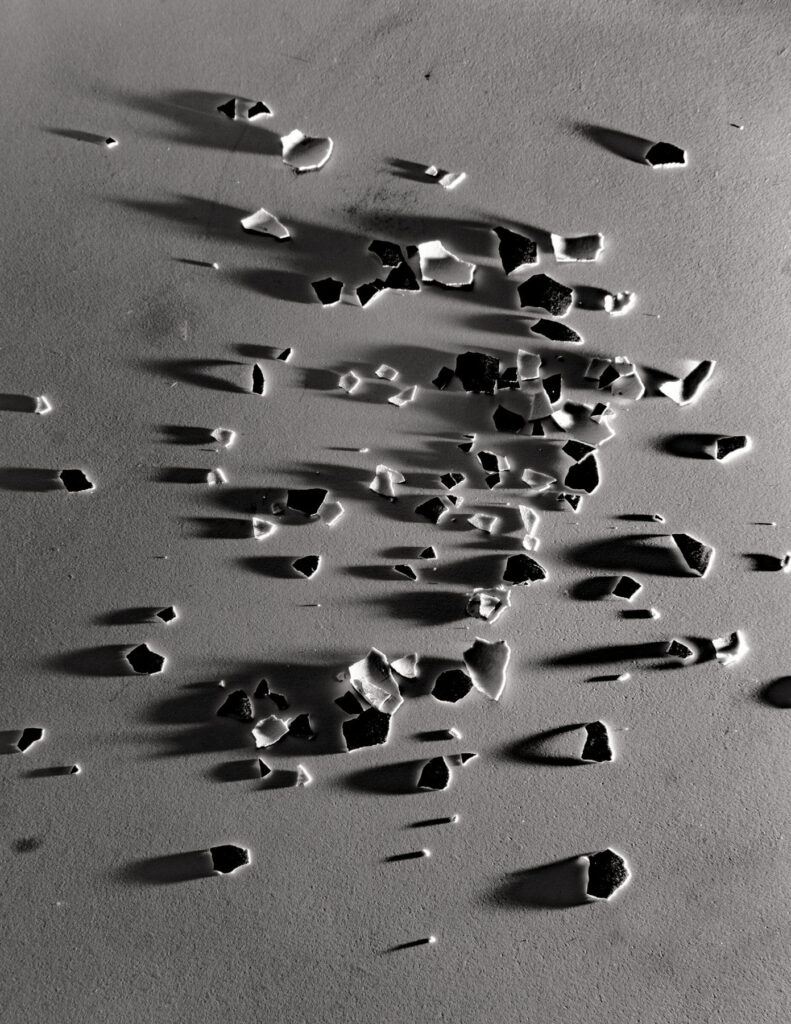

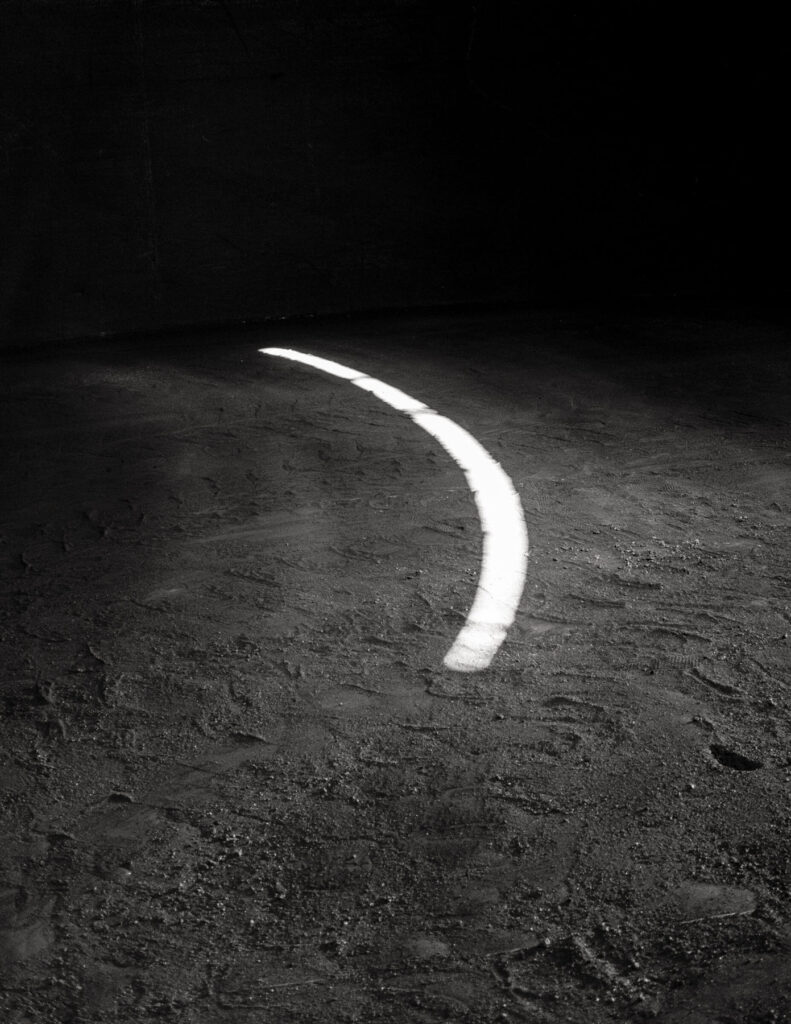

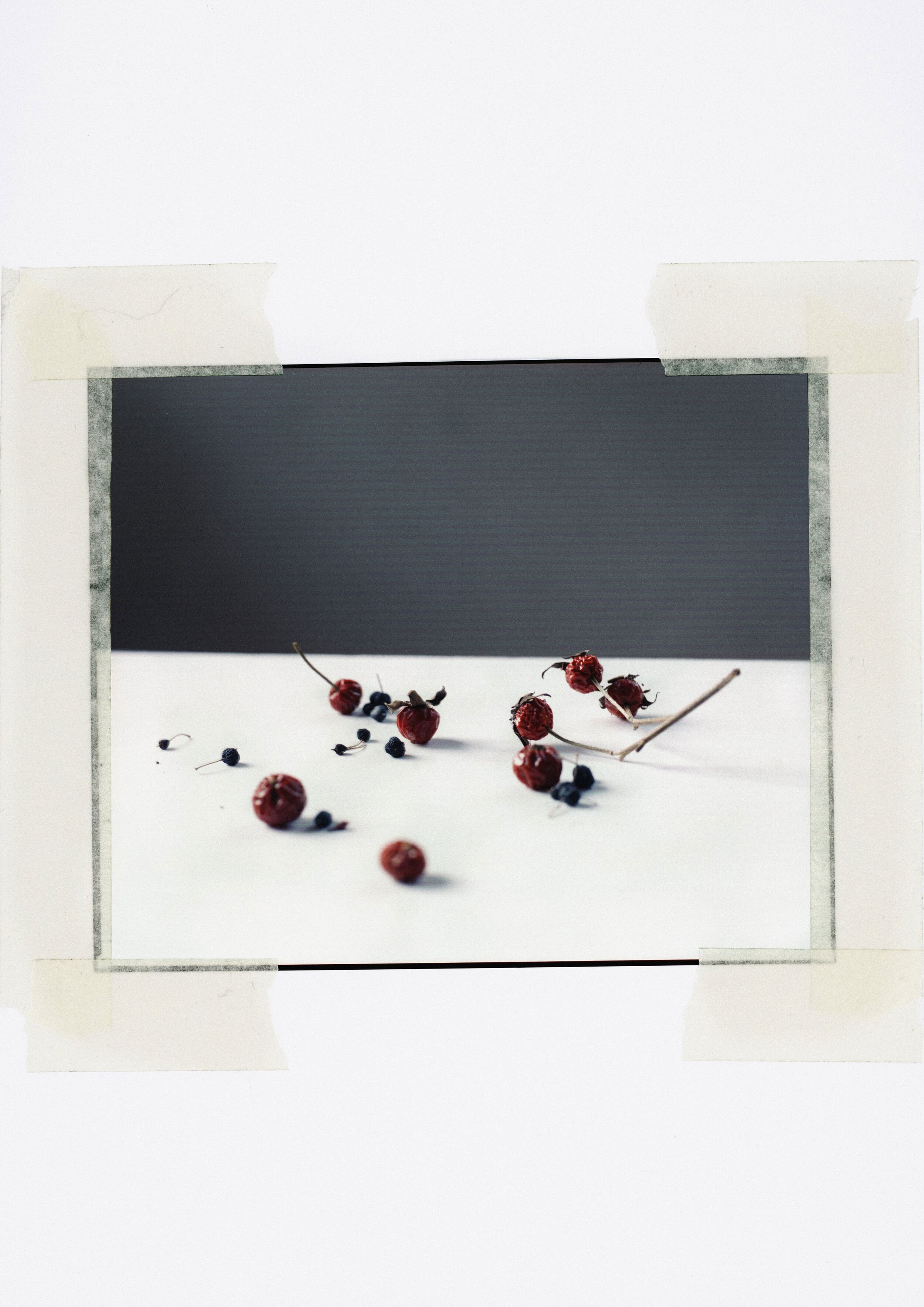

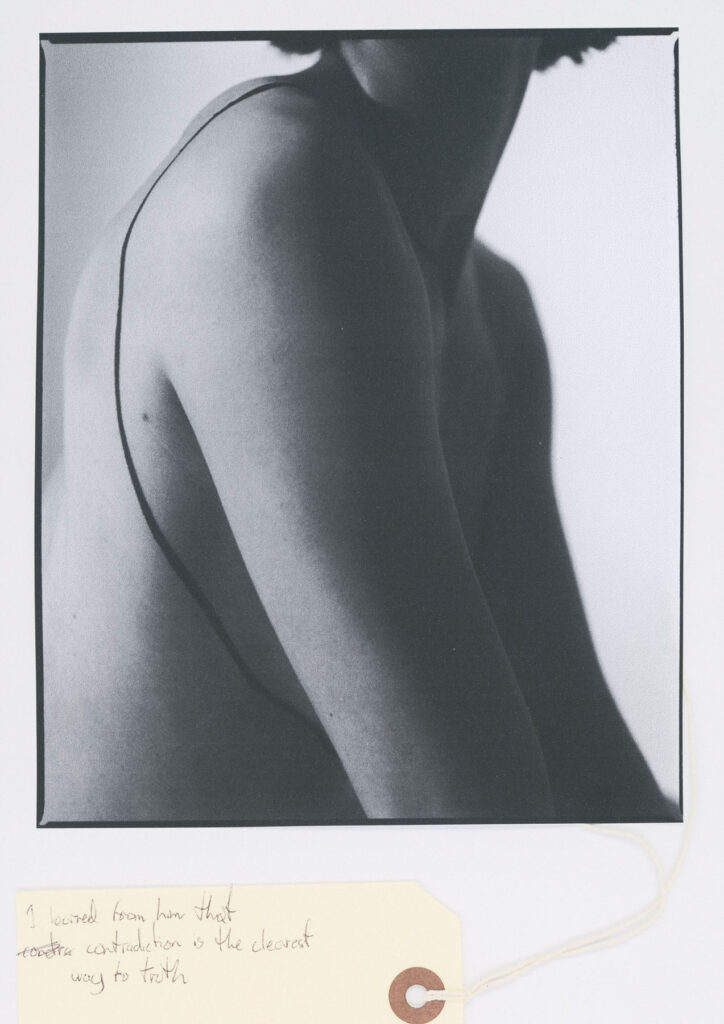

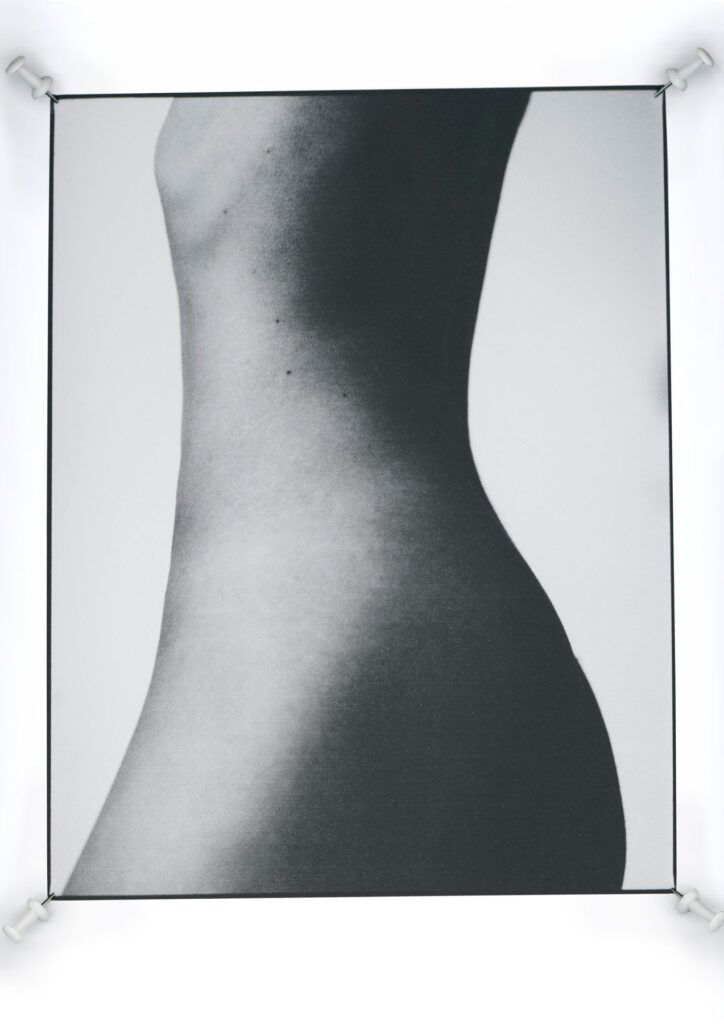

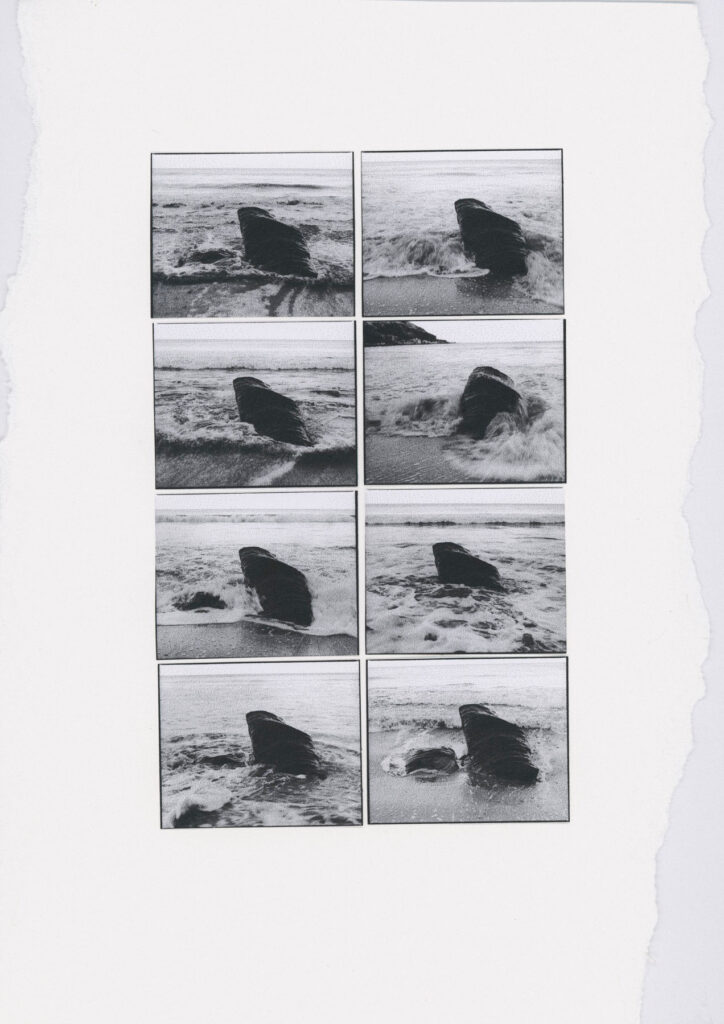

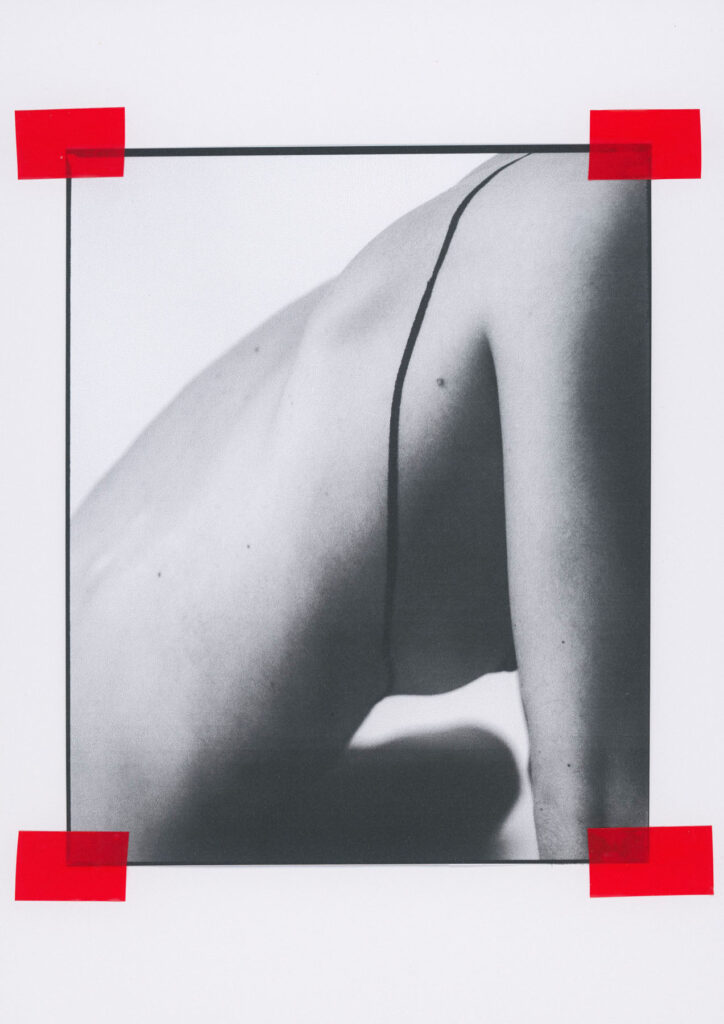

Self-consciousness is definitely a recurrent theme throughout the record, at least in its narrative aspects. In “Warp,” we depicted Zastar swimming in an abstract, undefined space, searching for objects to anchor her sense of reality and body. The goal we had in mind was to convey the feeling of a mind and body that had been separated and are now attempting to reunite in a quest to reinstate a feeling of individual wholeness. Rafael is one of the many visual artists we collaborate with; it is very important to us working with these incredible artists who help us give a visual body to our ideas.

I am very curious about the artistic direction of the release. There is an incredible emphasis on the aesthetic component of all your projects, your live gigs, the way you communicate online —All these visual elements seem to form a unicum with your sound, and, as you said, you collaborate a lot in order to achieve it. What fuels this curatorial approach that you have?

We always check Instagram! Scrolling, exploring all the time. We usually brainstorm a lot so that very precise images of what we want form in our minds. Those will then inform our research, and down the rabbit hole we go. The same thing applies to our collaboration with other musicians; we want to keep aesthetics and sonics parallel, informed by the same general idea.

You describe VMO as a multimedia performance art project. How do you approach creation? Does music come first or Is it about feeling and aesthetic rather than songwriting?

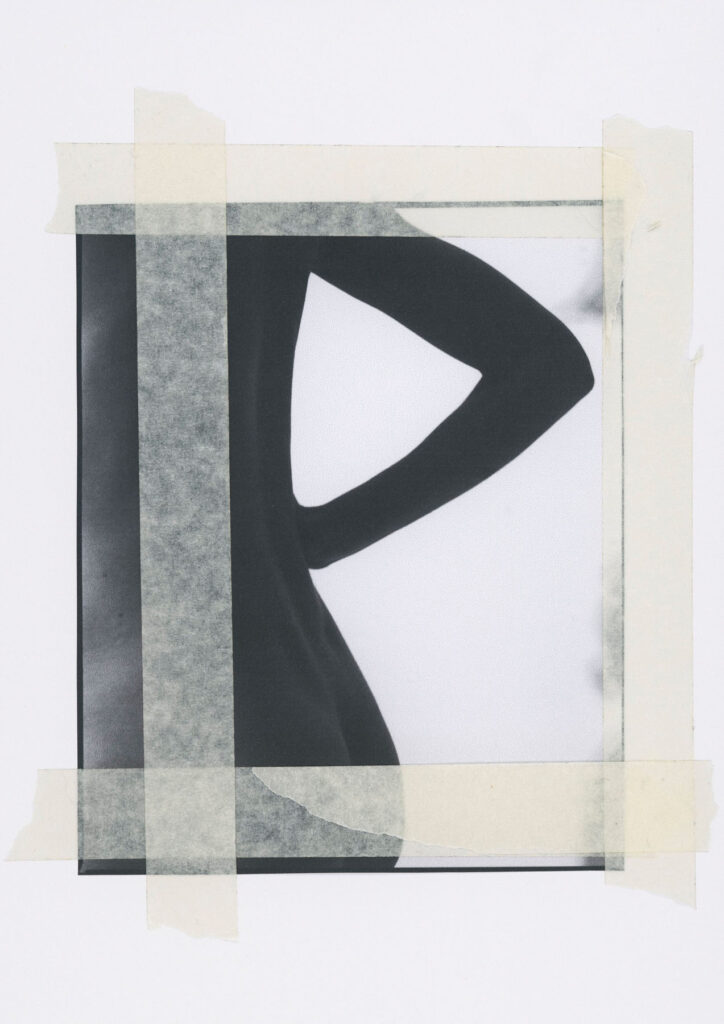

We operate precisely as an art collective, only our media is primarily music, trying to aggregate conceptual structures to sonic palettes. Visual and music, concepts and sounds. Everything usually starts with a visual idea of what we want to portray, and then from there, we work it into a sound and choose the people to work with on that overarching concept, musically and visually.

Interesting. Considering the multitude of influences you have and the collaborative nature of VMO, how do you function as a collective?

We work, well..collectively! [they laugh.] We usually gather inspiration from a variety of sources, books, poetry, films, music, nature..anything really. K, who functions as a sort of “chief curator” explains his influences and what he wants to do to all of us and then we work together to achieve the final result we want to go for.

You mentioned movies, literature, poetry. What were some of the extra-musical references for this particular record?

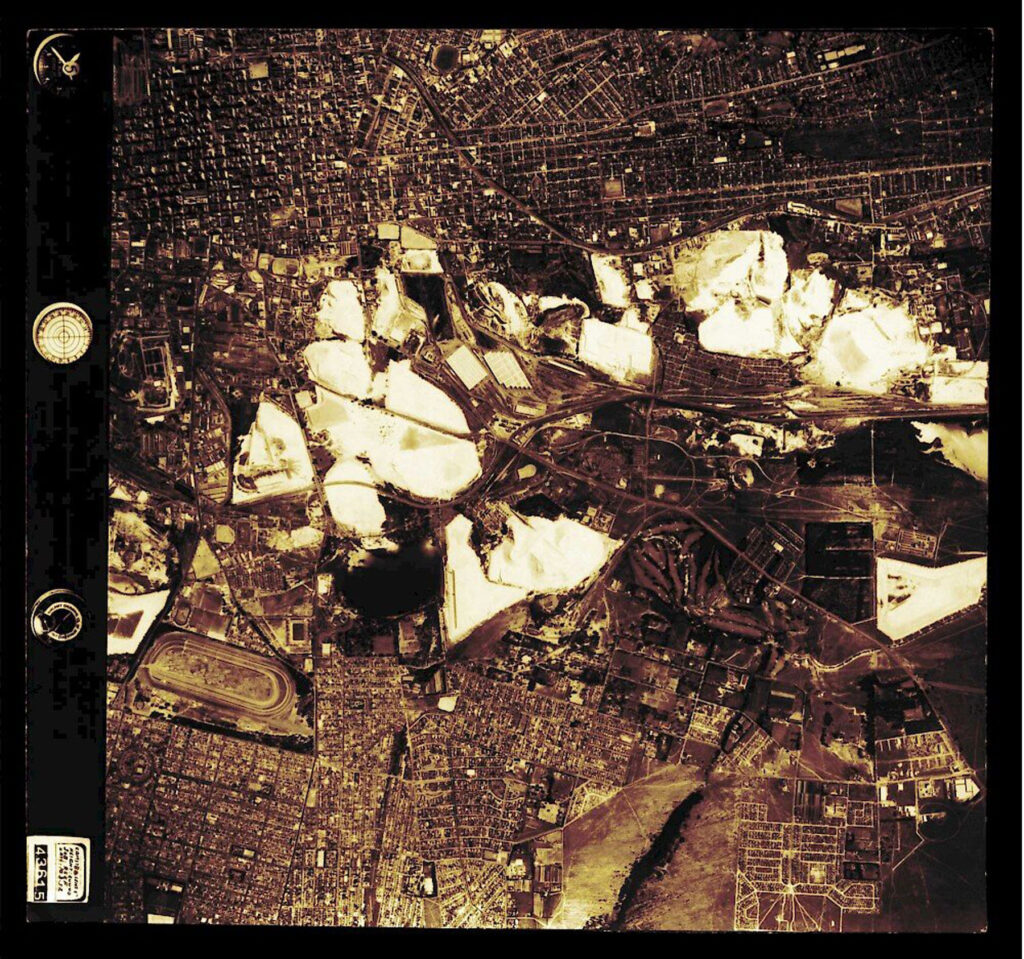

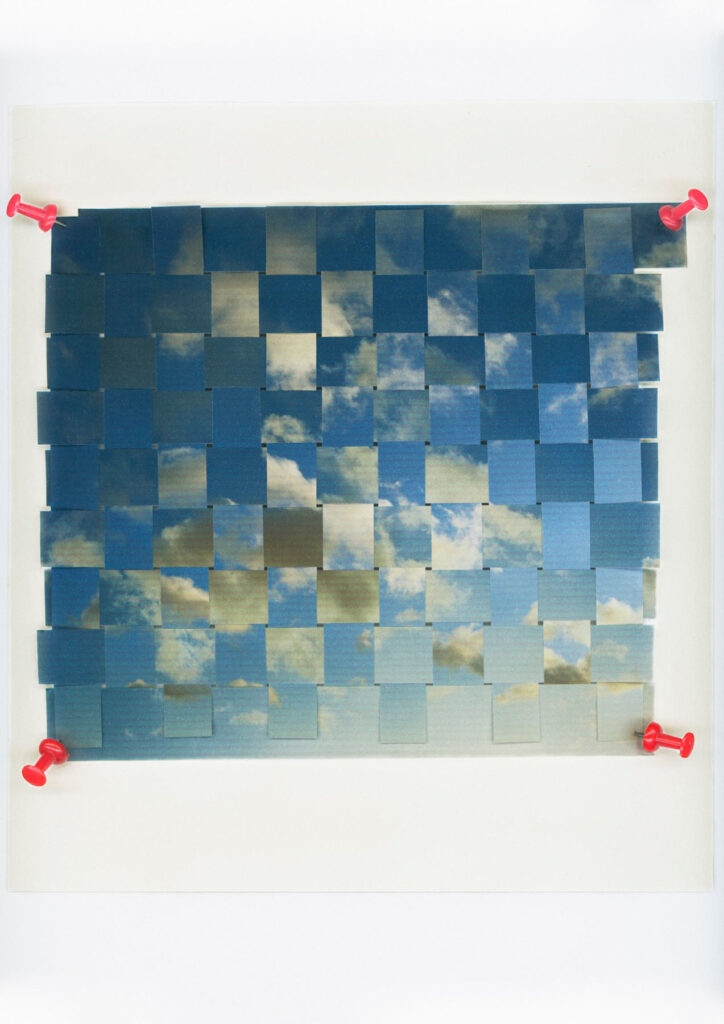

Each of us has his own individual inspiration, of course; we have a lot of different interests and media, drawing from various inspirations that manifest in our work. There are numerous histories occurring around the world all the time. For instance, Black Metal is influenced by Christianity, Afrofuturism is deeply ingrained in Detroit Techno —Different histories influence each other and are simultaneously distant yet close. Cross-pollination might very well be another of the main themes of the record. Think of “Stranger Things’ ‘; An incredibly pop show presenting a clear 80s aura, but mixing it with horror tropes in a quotational yet twisted manner.

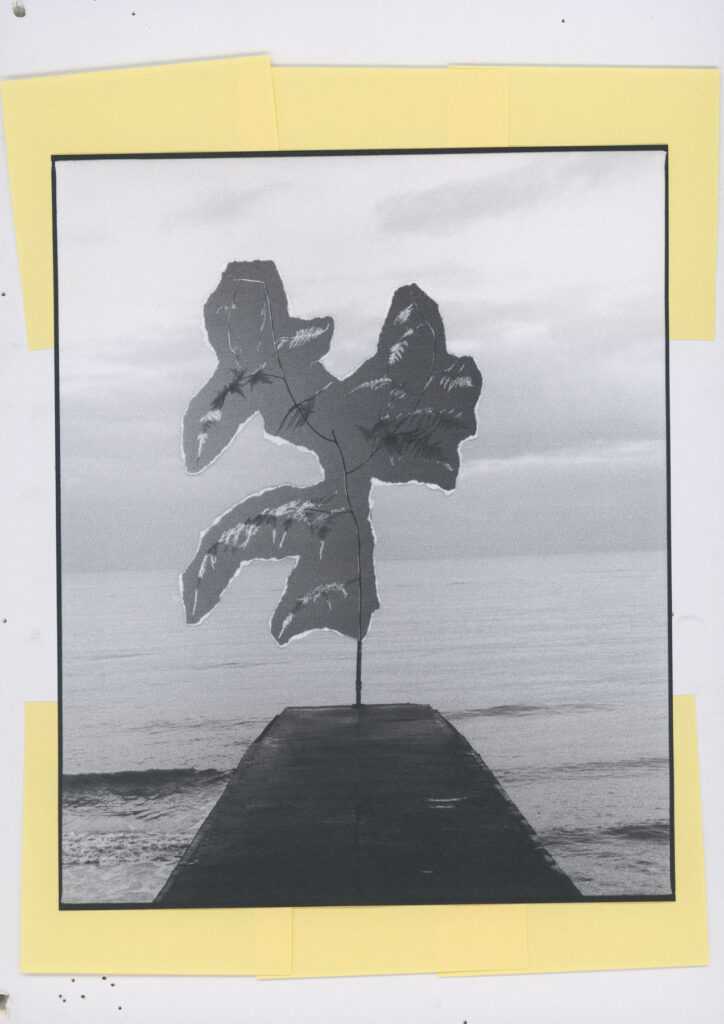

There’s an almost reassembled-collage quality to how you operate, exploring sonic dichotomies, musical and visual tropes, featuring elements that are at the same time disorienting but familiar —Yours is an almost unheimlich sound. How do you manage to keep all these different inputs together in a coherent result?

In a sense, it’s almost complete experimentation, and there’s a lot of trial and error. We take the time that we need to create something we believe its worthwhile, mixing focused work and abstraction. We try to convey abstract idea in precise sonic and visual coordinates, mixing the two up from time to time.

Another very important element in your work is saturation, both musically and visually. Your music challenges the listener, and I mean this in the best possible way. What made you gravitate towards such a confrontational sound?

We always were drawn to the physicality of certain music genres. Metal, gabber, techno: It’s kind of a natural thing for us to seek abstract ideas expressed through “violent” music. It is what we have always liked as listeners and artists.

Before we say goodbye, I wanted to ask: What’s a VMO live experience? Prepare us for the upcoming world tour!

We aim to create an environment that everyone can enjoy, almost like a theme park. However, we also improvise a lot, as every crowd is different and reacts differently, and we always try to go with the flow. It’s curious that we have this very, at times, complicated sound. However, what we want is to present and offer our performances to audiences in the most accommodating way possible. We aim to provide people with the easiest way possible for them to enjoy the experience itself.

Interview · Andrea Bratta

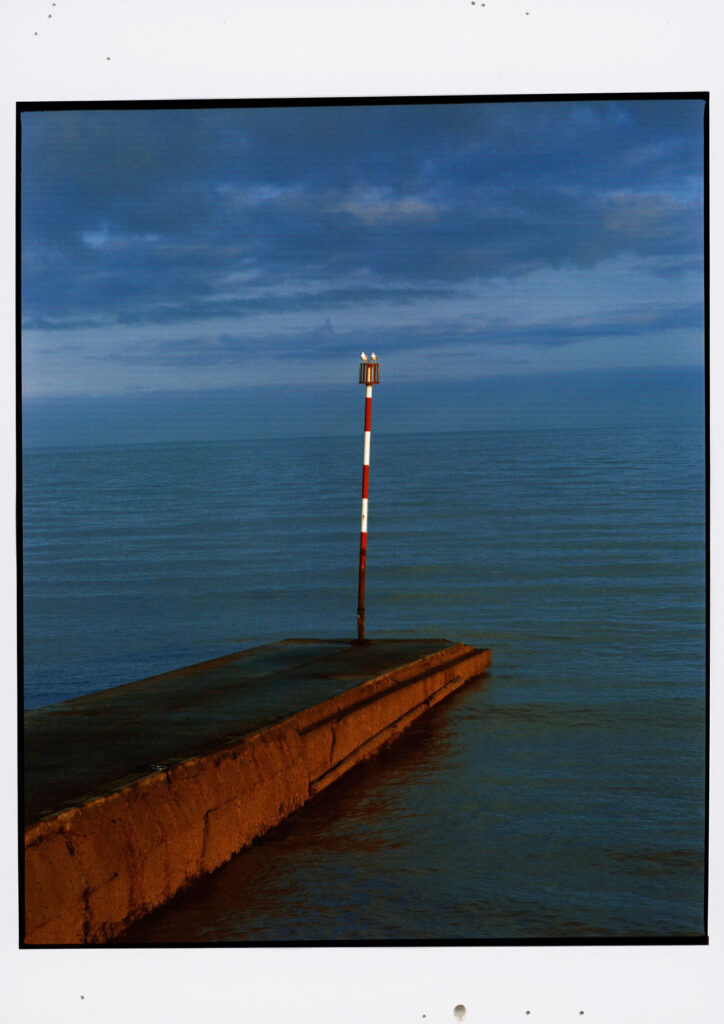

Photography (in order of appearance) · Genki Arata and Tatsuya Higuchi

Follow VMO on Instagram and Spotify

Follow NR on Instagram and Soundcloud