When Sumayya Vally founded the Johannesburg-based architectural studio Counterspace in 2015, it was against the backdrop of a deeply entrenched narrative of western hegemony. As an architectural student in South Africa, at the University of Pretoria and then the University of the Witwatersrand, Sumayya found the curriculum pivoted around a western worldview. And as the name implies, Counterspace seeks to redefine such a narrative, to amplify the lived experiences of those who have, historically, been overlooked. Earlier this year, Sumayya’s efforts to incorporate marginalised and underrepresented architectural ideas into an existing lexicon were internationally recognised when she was included as one of the TIME100’s most influential people.

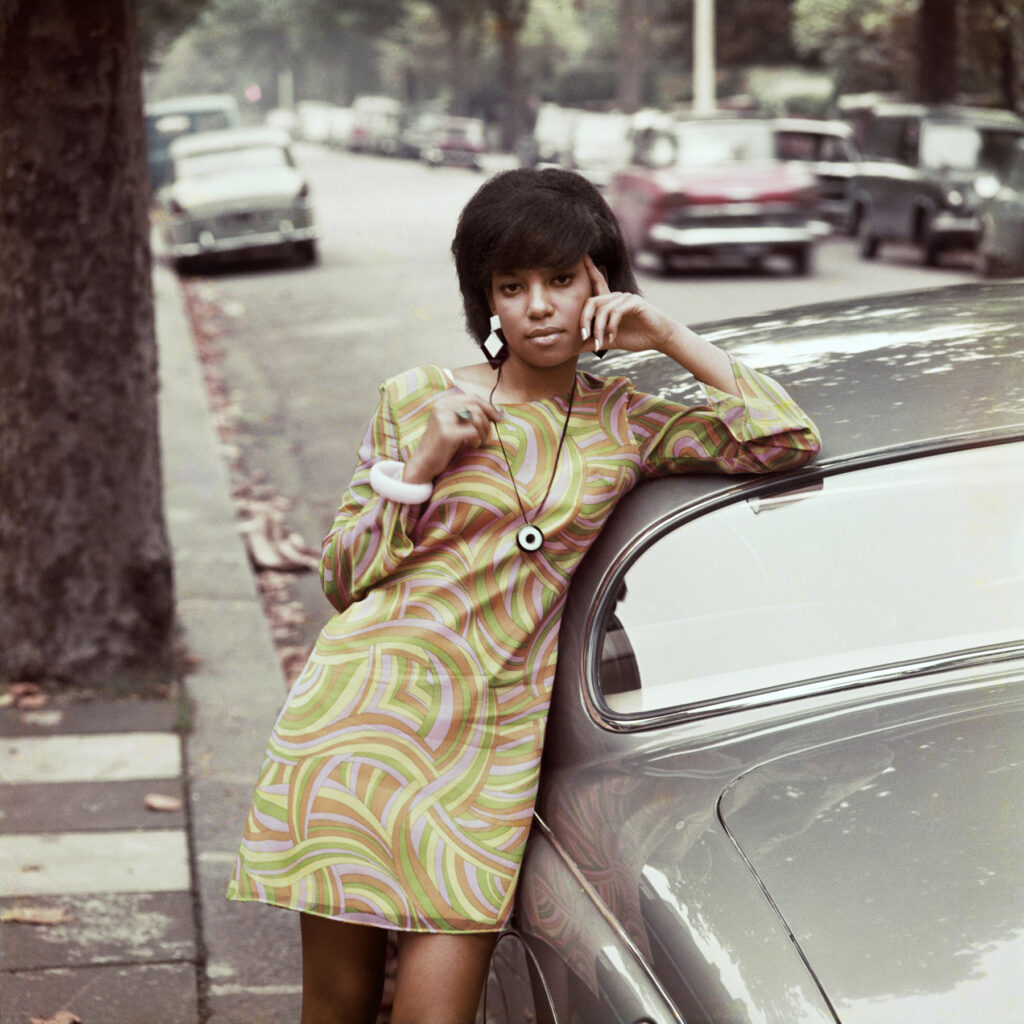

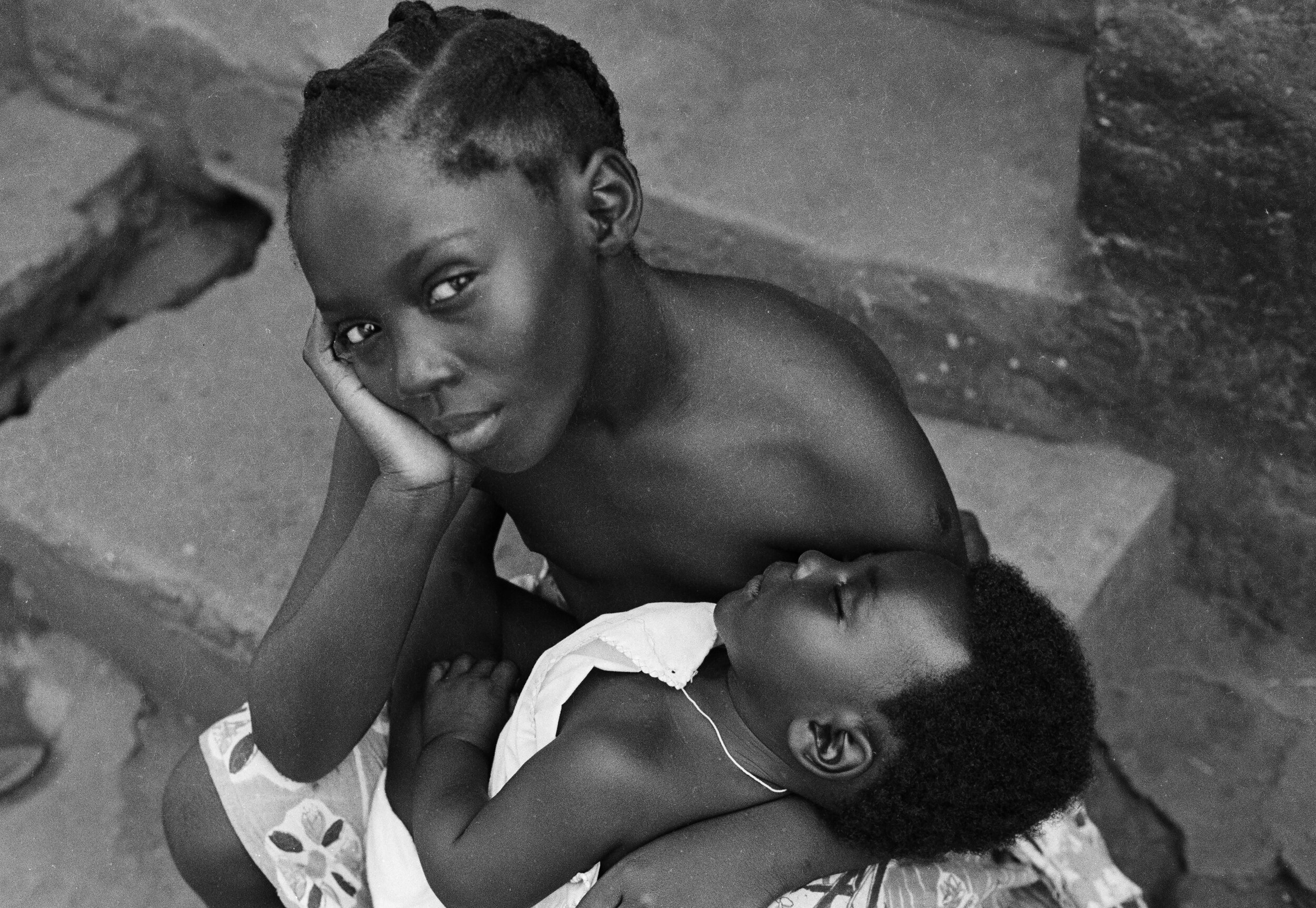

Sumayya’s architectural perspective is one shaped by her experience growing up in a place less openly inclusive, though equally diverse. Now 30, Sumayya’s early life was spent in the final years of Apartheid-era Pretoria. And as child, she experienced first-hand the impact that architecture and design can have on people’s lives. As South Africa nears 30 years since Apartheid’s end, it’s a country that remains deeply segregated by race, class and wealth. Architecture and city planning is not an innocent bystander here and have been used throughout history as tools for control, subordination, and exclusion. Sumayya’s exposure to this complicated reality informs the interdisciplinary, and often imaginative, work that Counterspace does.

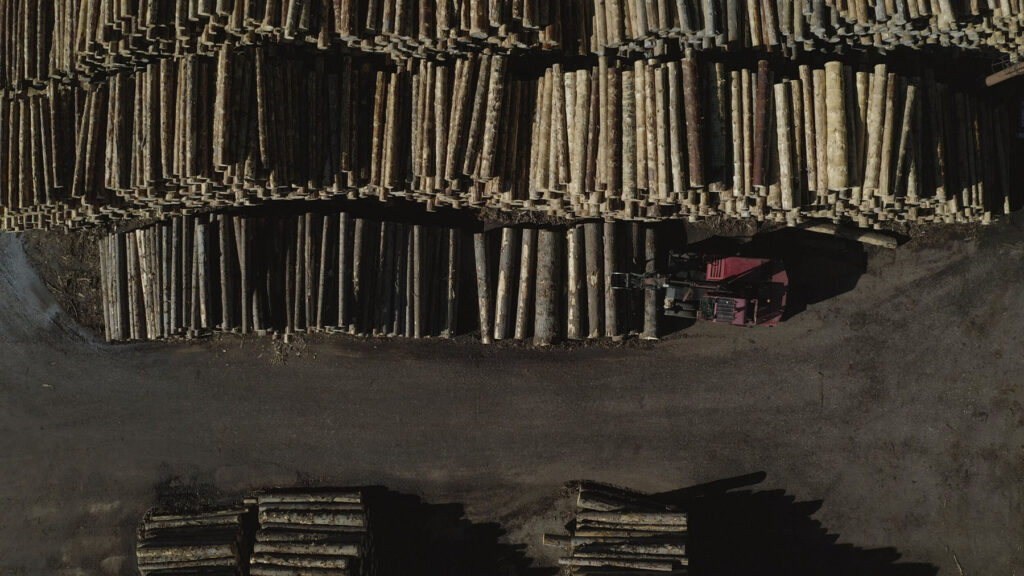

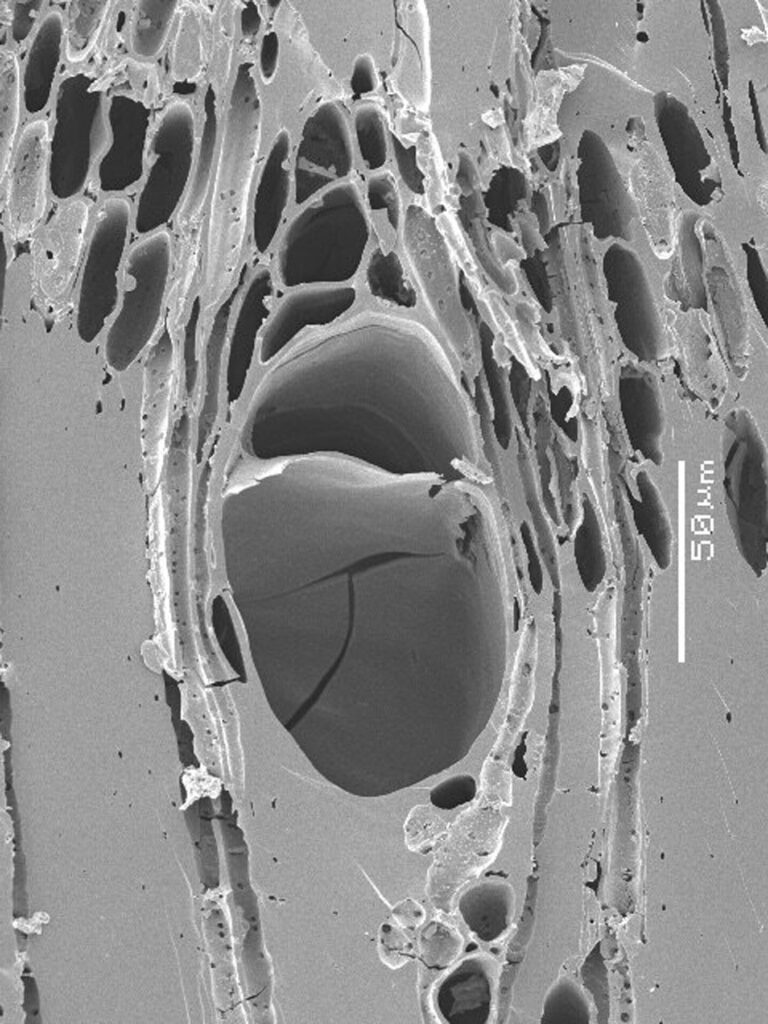

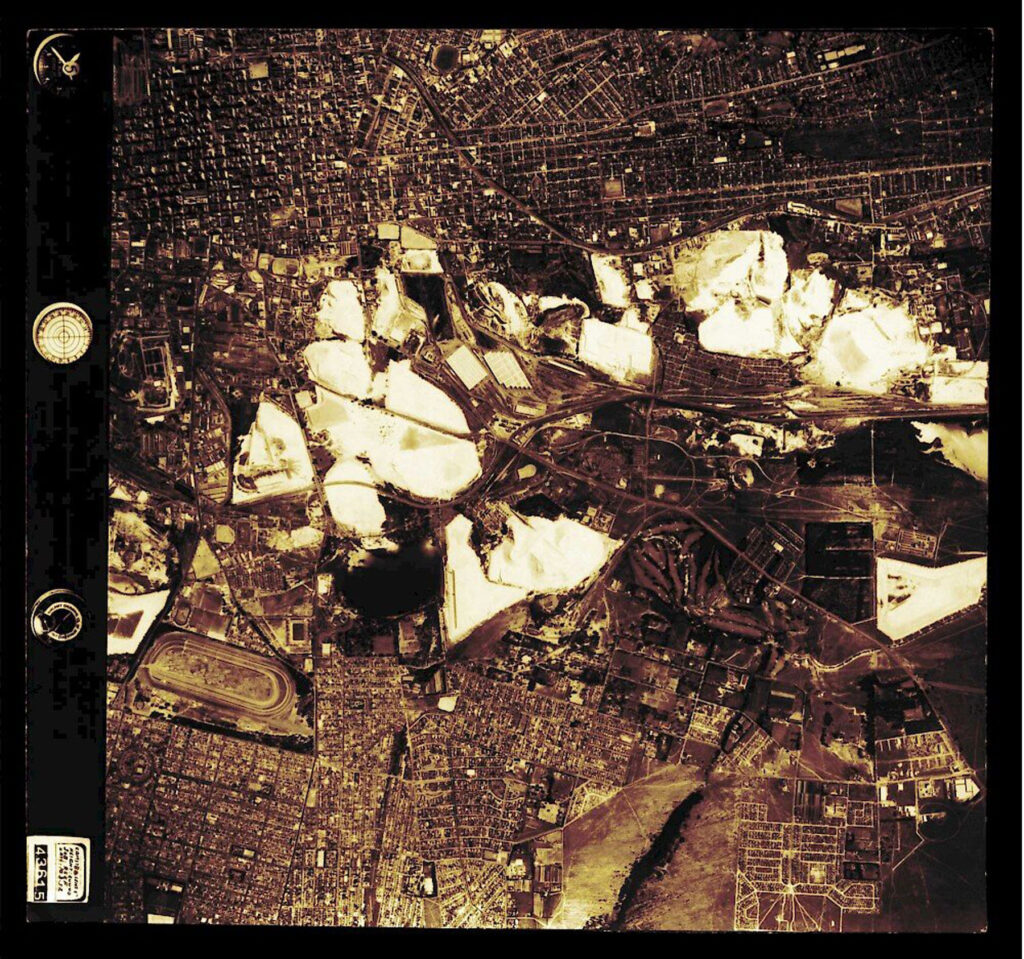

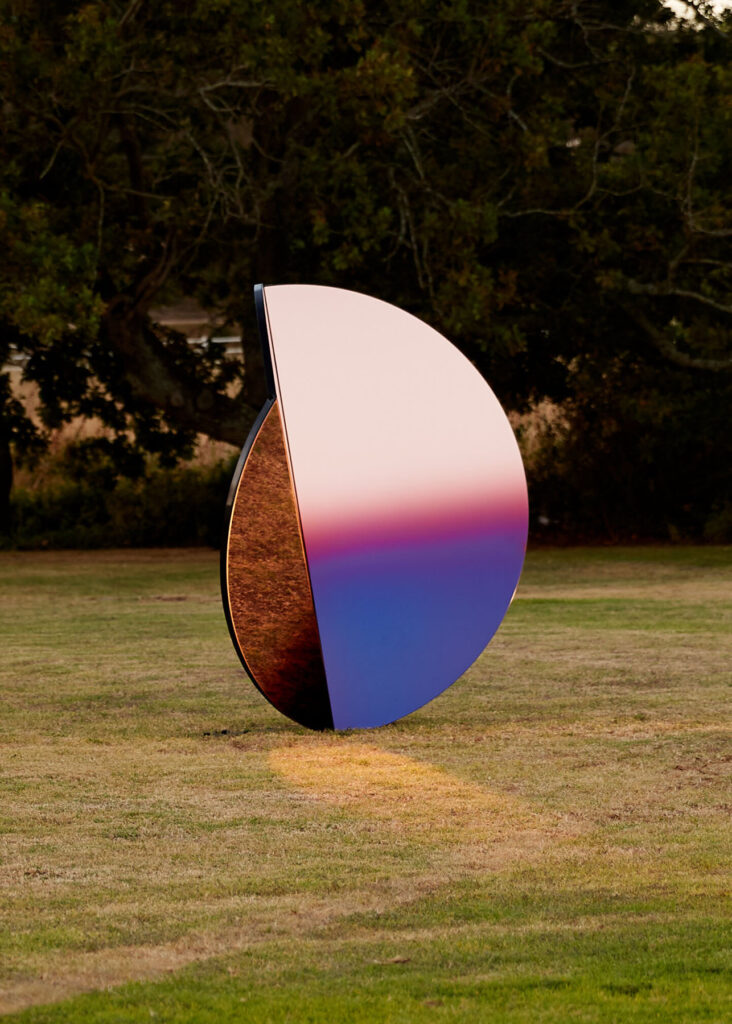

In 2019, the studio unveiled Folded Skies – a series of three sculptural structures made from interlocking tinted mirrors. The iridescent glow captured in the surfaces of the structures appears to represent the history of a city built on the vast gold deposits discovered in Johannesburg in the 1880s. While the legacy of this glittering past is reflected in the city’s colonial architecture, Folded Skies recalls instead the ecological aftermath of the gold rush. The city remains blighted by toxic pollution emanating from the equally vast number of waste dumps left behind from abandoned gold mines. The presence of these dumps is a reminder both of the aphorism that ‘everything that glitters is not gold’ and of the country’s history of segregation and suffering.

Johannesburg was a city divided right from the start, with mine-owners, wealthy from the gold rush, living separated, then segregated, lives from a black population who were eventually forced into townships in the city’s suburbs. The hangover of that gold discovery continues to wreak havoc. The large domineering heaps act as a physical barrier between rich and poor, black and white neighbourhoods; a reminder that segregation still exists. Toxic fumes from the dumps, which are themselves now being mined for the fragments of gold they may contain, are carried south by the wind, poisoning the black communities who live in their path – environmental racism in practise. Though human-made, the waste heaps demonstrate how materials can be used to control, to divide, to enslave people; as tools to construct a built environment, or as resources to build global trade.

By engaging with Johannesburg’s complicated history, Sumayya and Counterspace’s practice is as much social history as it is about designing for a better future. Uhmlaba, a film made in collaboration with the Guggenheim Museum, will explore South Africa’s history of segregation using soil (as land) as both its catalyst and focus. The studio often uses film and photography (archival and contemporary) to animate their ideas; visual evidence to demonstrate the fluidity of life and people in an urban environment. And if Johannesburg exemplifies how the architecture is used to control and segregate, the architect’s plan cannot always anticipate the unpredictability of the lived city experience. Counterspace celebrates, and designs, with small acts of subversion in mind. And so, as Sumayya explains in our conversation below, a new approach to architecture and the way we look and engage with urban spaces begins with interweaving unheard and overlooked histories into the fabric of our built environments.