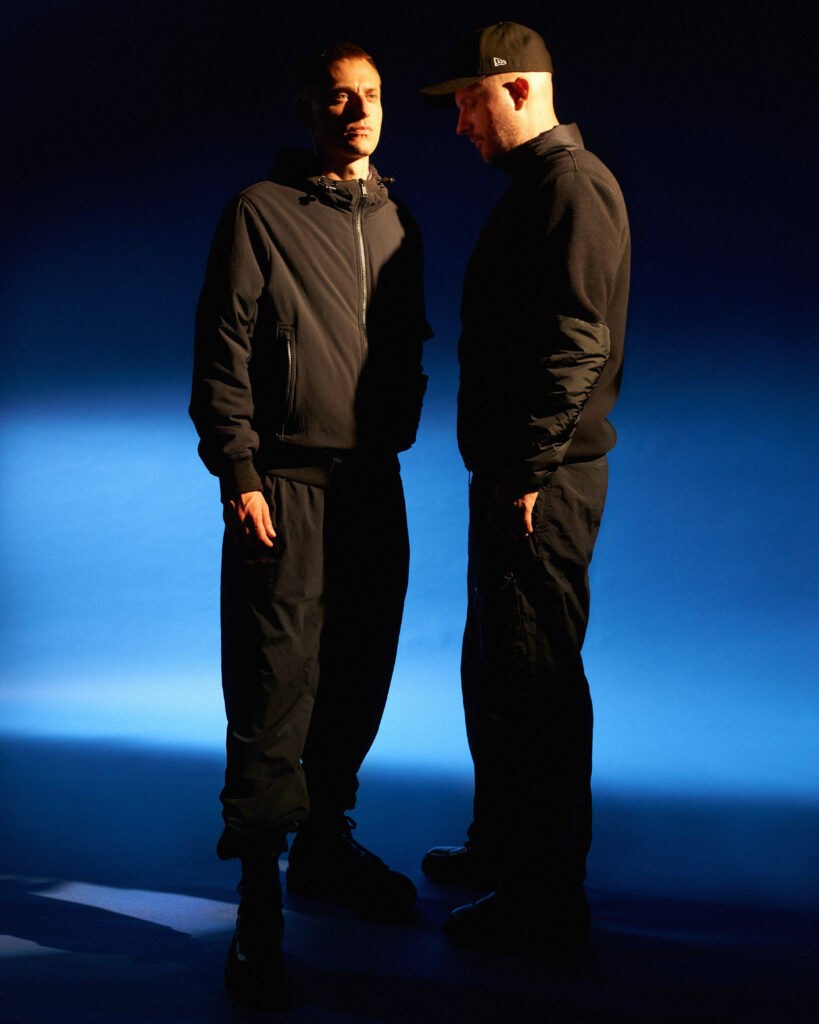

The In-Between: Overmono create a layered and boundary pushing sound that exists between emotional states.

Overmono are a UK electronic music duo made up of brothers Ed and Tom Russell. Raised in Wales, the siblings had individual success as producers before joining forces as Overmono. Wanting to reduce the influence of their individual pasts from the mix, they isolated themselves in a cottage and started to develop the foundation behind their music. Now, through a standing relationship with pioneering British label XL Recordings, they have released a series of layered and boundary-pushing work that define their distinctive sound today.

For this issue, NR had the opportunity to catch up with Ed and Tom to discuss their memories of growing up together, their experience of shaping Overmono to this point and their ambitions for the future.

Tom and Ed, thanks for joining us for this issue. I’ve been looking forward to having this conversation with you. I want to start by asking you about your memories growing up together, and what your individual influences and gravitations were because you’ve both done so much individually before Overmono.

T: I’m the elder of the two. Growing up in a house together, I was getting into rave music and Ed could hear the music through my bedroom door. I had turntables and some records and Ed got a pair of turntables when he was ridiculously young, like when he was around 10 years old. Then he was stealing records from my room, so there was some cross-pollination going on. As we got older, Ed developed his own taste and went on his own journey, and I developed mine and went on my own one, but it was all generally electronic music.

E: It feels like over the years our influences or what we were into individually were sometimes miles apart from each other, but then 6 months later we would come back and we’d be listening to the same thing.

“As we got older the distance between us got narrower and narrower, and nowadays it’s really rare that Tom plays me a record and I turn around and say “that’s shit, I don’t like it”..”

T: Haha when that does happens, I get really annoyed and I’m like you’re just not getting it!

E:Yeah haha, and these days we’re so similar in the sense of what we’re into, which from a writing point of view, makes everything pretty effortless because we both know what we like and what we want to try to achieve.

That connection is definitely felt in Overmono, but as a listener I can also hear and distinguish your individual influences feed into this project as well. Listening to your individual projects, it feels as Overmono is a cumulation of all those individual journeys. I’d love to hear more about you experience during those earlier projects – Tessela (Ed), and Truss, MPIA3 and Blacknecks (Tom).

T: I’ve always been really into Techno. Various styles of it. It has been a constant for me since my teens. I remember hearing Tanith on Tresor, it completely blew my mind and sent me down this rabbit hole. So, I just carried on doing that, and through the 2000’s I was getting more and more heavily into production, which led me into the projects you mentioned. I think for me, and I guess Ed can come back to this too because I’m speaking a bit for him as well, I felt really pinned in at the end. Because I’d done so much producing into a similar lane, I felt like that was what was expected of me. As much as I loved listening to that stuff, I felt like there were broader horizons I wanted to explore, and that inevitably led us down this path to start this project together.

E: I feel like we both started feeling that similar feeling around the same time. I remember releasing this one record and someone said to me “I’m all for artistic development, but where are the break beats?”. It got to a point that I felt like I had to put a break in every single tune otherwise people would be like this doesn’t sound right. Tom you were probably at a similar point with more distorted stuff..

T: Yeah, if I didn’t do something that was really tough and distorted it would just get no attention or traction. I could make something in 5 minutes that was distorted, and don’t get me wrong I love that sort of stuff, and people would go mad for it. But I could spend a couple of months crafting something and think it was one of the best things I’ve ever done, and nobody would care.

E: And That was a big thing both of us were going through around the same time. When you’re making music and figuring out your sound, cultivating it and honing it, it might feel really nice; to know exactly what you need to do to make something good because it becomes effortless. But after a while, when the expectation becomes “this is what you do” then, you start to think there’s so many other influences I have that I want to start to broaden what I do here. You end up feeling blocked from doing that.

“We got to a point that we were like “let’s just start making music together and see what that’s like. No one needs to know we’re doing it together, or that this project even exists. Let’s just write some music and see what that sounds like”.”

The series of first ten tracks we wrote, in a really short period of time – like 3 or 4 days – sounded quite different from our previous work but we were surprised by how cohesive it all sounded. There was no plan for it, we just said let’s take this equipment, go to this place, lock ourselves away, write some music and see what it sounds like.

T: It was so nice to be in this headspace where we had no expectations at all, and no personal expectations either. We just said “let’s go to this place, make some music and whatever happens, happens.” We had no intention to start the project at that point, we just wanted to write some new music together. The whole idea for Overmono came quite a bit afterwards. It was really amazing to have that freedom and it’s something we still try to maintain because it was so liberating.

E: It gets harder and harder the further down the road you get because the expectations start growing again, and once you put out a few records that have done well, it’s harder to come out with something that is really weird or super headsy. But that being said, we still have that same mentality that we try to go somewhere that isn’t our own studio, somewhere that is a different environment, somewhere that we can’t be contacted and we can’t contact other people. We just go there to sit and try to make some music.

“It’s that thing of disconnecting completely and forgetting about all the noise and any expectations. Then you end up writing some of the best stuff because we’re just having fun.”

Yeah, the Arla I-III series! It’s interesting to hear the process you went through to write this collection of tracks. I realise that you did projects together before this too, projects like TR//ER. To me, the Arla series definitely sounds like a more cohesive beginning or foundation to Overmono. I’d love to hear more about your process of forming your sound as Overmono at this earlier stage.

T: There was a lot of sampling in the Arla I-III EP series, and it was nice because I didn’t do a huge amount of sampling before so it was a fresh perspective in production for me, and – I learned a lot from watching Ed because he’s great at it, and for me this was cool because it was an area of production that I wasn’t familiar with and got to explore.

I was given, as a long term loan, a large record collection from my brother in law, which was a DJ in Leeds in the late 80’s and early 90’s. He had loads of old House and Techno records, and it was just in his basement collecting dust and getting a bit of mould on it,. So, I was like I can take care of it for you. But it turned out there were only a few good records in there, and most of it was utter crap – white labels that probably never made it to an official release, but it was still a pretty good archive of early British House and Techno. We decided to make something out of it, so we went through it all and started to make this huge sample bank. That was kind of the foundation of a lot of the Arla tracks. This is also maybe why they have a cohesiveness because they were recorded through the same turntable and through the same process.

E: They were so dusty weren’t they…

T: So dusty! So much crackle and noise, and it’s also why those tracks don’t translate to sound systems very well haha. A lot of it again, was me watching Ed using the sampler and also Ableton, because to that point I was mostly a Cubase user for all my life. Ed kept asking me to switch over to Ableton and I was like “Nah, I’m used to Cubase, that’s what I know – blah…-blah blah…” After a few days in the cottage writing the Area stuff, and watching Ed use Ableton, I was like holy fuck I gotta start using this! It made other stuff look so archaic. The amount of times I would try to set up a side-chain in Cubase and I couldn’t be arsed because it was so long-winded, and then watching Ed do it in seconds. Also, seeing how you could manipulate samples with warps and time stretches was really inspiring.

E: I think during this session we had a few synth lines that have been just sitting around, so we started to process them through the same process that we were using for the record collection, so that added a different dimension to them. If you listen to original Arla samples a lot of them have a late 80’s sound to them but we just mangled them over and over till it didn’t sound like that.

Because we weren’t in our studio, we just rented a cottage in south wales, we had a limited amount of equipment with us. We had a small mixing desk, two speakers…

T: Didn’t we borrow an Allen & Heath?

E: Yeah! We borrowed an Allen & Heath mixer from David.

T: Shout out to him for lending that to us. Everything went through that and we also had a Lexicon PCM 80. I don’t know if we had any other effects?

E: We just had that one Reverb, and we took a Virus C synth, and probably a compressor. Think there was another synth as well…

T: We took the JD 800, didn’t we?

E: Yeah it was the JD 800! Haha.

T: Haha it’s pretty much the heaviest synth we could fit in the car.

E: It was this beast of a synth that we only ended up using for one day. The rest of the days we were super productive and for one day we just dicked around for 6 hours on the JD 800, and we thought the stuff we wrote was super deep. The next morning we listened to the track and we were like “Jesus christ that one’s getting axed” haha!. I think it made it to some of the tracks at the end though. It was a bit fucked up and it sometime would go weird and out of tune. You would be recording a synth line and move a fader or open up a filter a tiny bit, and it would go mad! So we chopped some of those bits up and put them into the tracks too.

You could feel that, considering the amount of tracks in the series, there were different approaches between them. Going from a track like O-Coast to Phase Magenta to something like Harp Open, although there was definitely a cohesiveness, you could tell that there were different influences and gravitations behind each of them as well. I want to ask you about your first studio in Bromley, and your experience of setting up that studio together shortly after the Arla series.

E: After that time writing in the cottage, we both had separate studios for a bit. Tom had a studio in Soho and I would go there quite a lot. The studio was right across from Black Market Records, and we would end up writing a lot of the stuff at his studio. I had a studio in my flat too, and we split our time between there and Tom’s studio.

That was really good for a while, but after a bit we thought let’s combine all our gear to one big studio because we were writing so much together. It just so happened that this really big studio was becoming available in Bromley, which is a half an hour south of Peckham. It hadn’t been touched since the mid 90’s. It had this swirly paint job that was pealing off, and old school carpets with fag burns all over it. That said, it had a good feeling to it. It had this massive control room, a live room and a kitchen. It was big enough to play a five-a- side football game. So we decided to take it.

We set it up into two rooms. All the stuff that we used less often or used for our live shows one live room. There would be a bunch of synths set up with loads of effect pedals – and some random kit that we collected over the years. You could spend a day in there and have the freedom to start recording loads of stuff with all the gear, which was really fun. Then you had the control room that was properly a sound-proofed studio, which had all our gear set up in it and sounded amazing. That’s where we’d work on the tracks together. We were in that studio for three and a half years, and we spent quite a lot freshening it up. We took all the carpets off and sanding the floors back, but unfortunately the whole building got sold to developers. It was such a unique place. It was in the middle of nowhere.

T: It was the most unassuming place for a studio, just in the ass-end of absolutely nowhere –

E: There were no other studios there. It was opposite a chip shop, above a church, beneath a magazine printer, so it was so random. I remember every now and then we had someone come over to produce something with us. We had VK, a drill producer, come over and when I went down to get him, he was like “nah, don’t know about this”. You had to go through this bin store and get to these industrial stairs and I remember looking at him and he was like “this isn’t right”.

T: The previous occupant put up these weird hospital signs, like “blood unit this way” or “radio therapy that way”…- obviously trying to put people off it.

E: It looked like a really weird NHS unit and was sort of an outlier. But yeah we were there for three and a half years and it was amazing. We wrote a lot of the Overmono stuff there. Still, when we had that studio we would book times to go away. We went to a remote hut in the Isle of Sky in the Highlands of Scotland. We would get as much gear as we could and fit it into a few peli cases to fly with. We would always keep that mentality of taking some gear and go write for however many days; where all routine could go out the window, to see what we come up with. Sometimes in five days we’d end up doing what we did in three months in the studio. But yeah R.I.P Bromley studios, we really loved our time there and it was an amazing place.

T: Yeah it really was!

One of the things that really stuck out to me reading about you in the past was you saying that you always felt like “you were always looking in from the outside”, even from early on in your careers. That you grew up outside of a big city and it never concerned you what the trend was at that time. I feel that these moments where you disconnect yourselves have been so potent because it’s so close to what’s been true to you from the beginning.

A track that I listened to a lot early on when I was getting into your music was actually called Bromley, which you did together with Joy Orbison. Before we move on from your time at Bromley, I want to ask you about your experience of working with Joy O, and also discuss the tracks you mentioned you made towards the end of this period because they’re some of my favourite work you’ve produced together.

E: The stuff with Joy Orbison started when he came to the studio a couple of times. We started to hang out and record a few things, so we decided to work on something official together. I remember I sent him a rough idea before and he was into releasing it on his label Hinge Finger, but I never ended up finishing it. So we thought “why don’t the three of us try to work on this track together and maybe we can get it to something that’s more finished”. We started pulling some of the stems from the original idea and started working on it together at the studio in Bromley.

“Us and Pete (Joy Orbison) have totally different working methods. For us, we’re really instinctual and we don’t really think of rules and structures.”

T: I think we’re just too disorganised for that kind of stuff. Personally I just don’t have the patience to stick with something for too long if I’m struggling with an idea. Ed usually perseveres longer than me, and often there are times it’s the right thing to do because the track gets cracking on.

E: Pete can persevere the longest, I’d say.

T: He has an unbelievable ability to stay laser focused on something. He can make these decisions hours and hours after being at the studio, where I’m just like I don’t know what’s going on anymore. He has an amazing ability to do that.

Really interesting to hear the story of how that all came together. I want to talk to you about your more recent releases on XL Recordings like Cash Romantic. I’m interested to hear about your process of shaping the sound behind these more recent releases.

T: By the time we moved away from the Arla series, we started using samples less and less, and we actually started making our own sample bank. We spent some time making up loops, synth lines and chord progressions that make a large sample bank that we now share. So a lot of these more recent tracks, their start points are from these samples we made. Gunk, for instance, is from a synth line that we originally came up with for our I Have A Love Remix, which is actually the last ever track we made at Bromley studios. So it was a really nice way for us to start Gunk off like that because that track – I Have A Love (Overmono Remix) – was a really special track for us. I think over the years, developing this sample bank that’s made of all our own samples, is a big part of our sound and serves as an important jumping off point for us. We started programming our own drums and aren’t doing much break-beat’s anymore. For example, the drums for Cash Romantic, the title track, is made from all programmed drums from a contact multi-sample drum pack. There’s no actual old sample break-beat, but instead everything’s much more processed.

“We always want to bring out the most grit and character we can out of things. Most of the time we have to use stuff in a way that they’re not designed to be used.”

That might be, for example, using an EQ to boost stuff so harshly that it starts distorting, but once you take that in the computer you can bring it back a little bit and take away some of the harshness.

“It’s about building layers of character and a sense of physical space. I struggle sometimes when listening to music that is too clinical or clean because there is this lack of physical space. That’s something we think about a lot; how the music itself sounds in relation to its space. Even if you’re listening with headphones with no interaction with the space around you, does it feel like it’s in its own space? And I think a lot of that comes from getting it out and running it through the different cables.”

It sounds like you’ve simplified or programmed your set up so that it’s more responsive to your making process, and that creates space for you to be more instinctive and expressive when shaping your sound.

I’m curious to hear more about the story behind the imagery and visual content of your recent releases as well, and about your partnership with Rollo Jackson in creating that content.

E: There’s a few things that came together with the imagery. Mean dogs have traditionally been used in UK rave music like in old Drum & Bass records, and there was always this thing of dogs on chains snarling at the camera. It was something that became quite pastiche and didn’t age that well. Dobermans are perceived as these” vicious dogs”, but they’re not at all. That’s just how they’re trained and how people portray them to be. They’re actually really lovely and friendly dogs. So we thought “why don’t we do these sleeves with Dobermans on them?”. As soon as you tell someone “I have two Dobermans sat in a BMW on the cover of my album” they’re like “oh, that’s a bit cliché.”

T: And part gangster..

E: Yeah, haha! But they actually look quite playful and dopey, and in reality they are actually really playful.

“From a musical point of view that ambiguity of emotion is something we always gravitate towards. Something that feels like it’s between a few different emotional states. I think that’s what those dogs represent. Because of how we’re brought up to view Dobermans, when you portray them in a different way, you instantly feel like your are conflicted between different emotional states.”

You ask yourself “is this supposed to look aggressive and mean, or is it just lovely dogs being playful?”

Rollo (Jackson) has such an incredible eye and is able to see things in such a unique way. So many of the shoots we’ve done have been serendipitous. When we were shooting the cover for Everything You Need, it was in the carpark of the Bromley Football Club because we got kicked out of the other location. We showed up in a van with a couple Dobermans and a Boxer and they were like “what the fuck you guys doing?” haha

T: Haha, they were like, “get off our property!”

E: So we went to the football club and they were more accommodating. I just remember the sun coming out from behind the clouds and bouncing off the leather seats of the BMW, and we all looked at each other and were like that is it, that’s got to be the shot. And there’s still so much more to explore with that.

T: Also with Rollo, he’s so deeply involved in UK music culture. He has such a knowledge of UK dance music, specially London-centric forms of music, so he really gets where we’re coming from. Because of that we really feel like there’s a kinship there between us and we can really trust in his judgment of what we’re trying to achieve. Also, his judgment of what to avoid specially, like things that might be a bit pastiche, brings a fresh angle too while we explore things that we’re collectively into.

I think this is a good point to ask you about your live shows and how this imagery ties into it. I’m curious to hear about how your live set up has evolved over the years and where you hope to take it next, as you are now embarking on on your UK, European and US headline tour.

T: It’s a bit more professional these days that’s for sure, haha, It was a fucking mess back in day! We started with a booking request from Ireland in Limerick, and this was before Overmono even existed and before we did anything together. They were like “Would Ed and Tom like to play together?” and we were like “we’ve never done that or hinted that we wanted to do that together haha, but sure yeah why not!” So, suddenly we needed to figure out a techno live set-up. We had only released one track and suddenly we started getting a few gigs together. We were travelling around with the most insane amount of kit. We had this colour-coded pillow case system with different leads and cables in them. We had a blue pillow for our midi leads, a red one for our power cables, and a black one for our audio cables. They were all crammed into these giant peli cases with the rest of our gear. They would take two hours to set up and two hours to take down. We’d take some gear like a big drum machine and we’d only use it for 5 minutes.

E: I remember you used this synth that didn’t have any controls on it..

T: The EX, the Korg EX-800 desktop version!

E: Yeah haha, you’d be playing a pad off it and you’d want to open up the filter and you had to press this button to find the filter and keep pressing it to turn it up… it was a mess and quite lawless. We would just have to improvise and some of the shows were alright and some of them were terrible.. So by the time we started doing stuff together as Overmono we already had learned a lot. When you’re playing electronic music live, there are these pit-falls that are waiting for you to fall into and you have to spend some time navigating those from a technical point of view.

“Performing electronic music live is a big technical process that needs to be continuously worked on and refined.”

For the first few years after every Overmono live show, we would almost redo the entire live show after every gig. We would sit down in our hotel room after every show with a notepad and write down all the things we wanted to change or improve. We would write down what worked and what didn’t work, and record all the technical problems we had in the show. We would keep repeating this and over the years we started honing in on what it worked for us from a performance and technical point of view.

Now we’re in such a different spot, the set up hasn’t changed for six months, which is a new personal record for us. We feel more confident and comfortable than ever because we spent a long time developing a set up that is all properly functioning and cabled so it feels more professional. That means we can focus and have fun with the performance side of it, instead of worrying about why that drum machine went out of time again. But now our headspace can be filled with the more exciting stuff like wondering what I can make with these drums do for the next five minutes, and do something interesting and weird.

The next logical step was figuring out the visual side of things, and for a long time we were figuring that out ourselves. But generally we had no idea what we were doing, so we just borrowed a bunch of modular video gear and recorded a lot of things out of it.

T: It looked good on a tiny screen and we were like that’s killer, but then got to a festival with a giant LED screen and it looked so bad and so pixelated.

E: Now, we thankfully got more people on board to do that with us. We’re still pretty heavily involved because we have a clear idea of what it should be. So we’re more directly involved in the creative direction of the visual content, but now we have people that actually know how to use that gear. The visuals are generally split between footage that Rollo captured, like thermal images of the Dobermans running through a field, and then a lot of processed content we created with a visualiser called Innerstrings, who uses a lot of the same gear we were using but knows how to use it and he’s great with it. That’s enabled us to grow the show to what it is now, and we have ambitions to take it even further.

T: Like Ed said, the live show is something we are so deeply passionate about and something we’re continuously trying to grow. To make it more of an immersive experience in every step and try to think of the evolution of it. So that’s a big priority for us, but the biggest priority is to always keep writing and making music every opportunity we have.

“Our aim is to keep progressing and moving forward in writing music that we think is an evolution from where we were before.”

E: Going back to the live show, thinking about the covers we made with Rollo Jackson and our ambitions for the future, the live show gives us the chance to expand that into something more cinematic and the sleeve images start to feel more real.

“You suddenly feel like that whole world has opened up, so the further along we go the bigger we want that feeling to be. You see a Doberman running through a 50 meter screen, it’s just glorious and there’s nothing better. That’s what we want to keep growing and pushing towards.”

Team

Talents Tom and Ed Russell (Overmono)

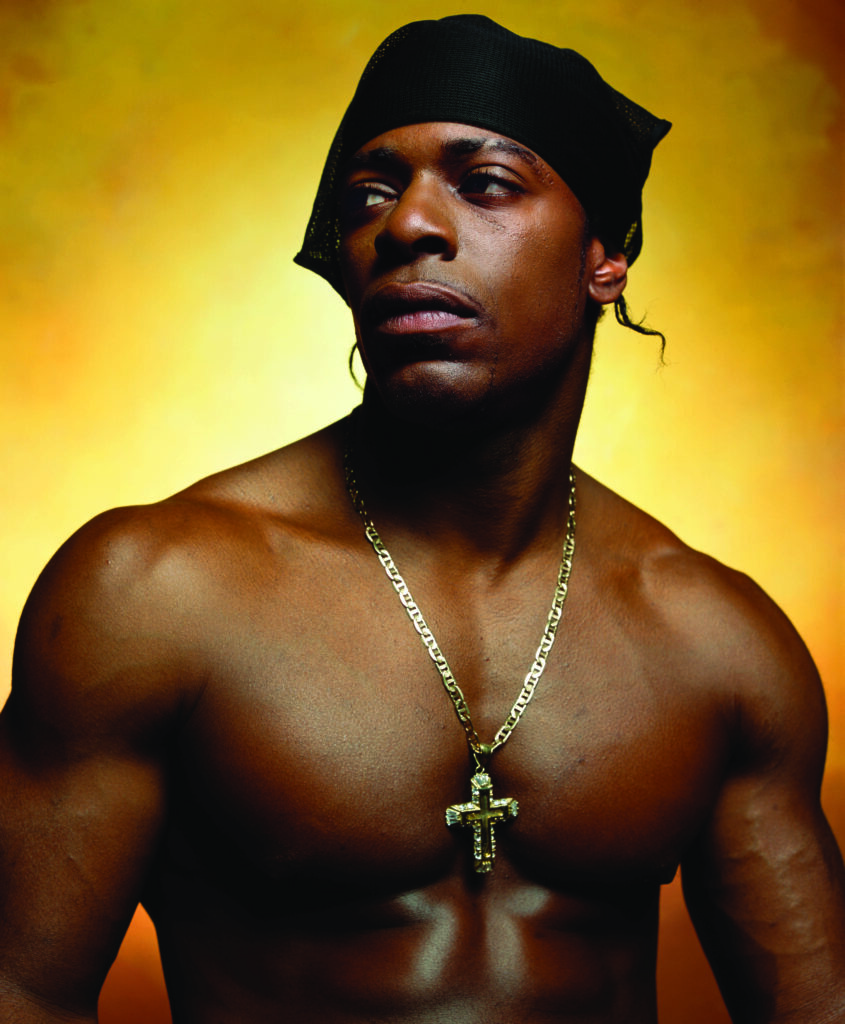

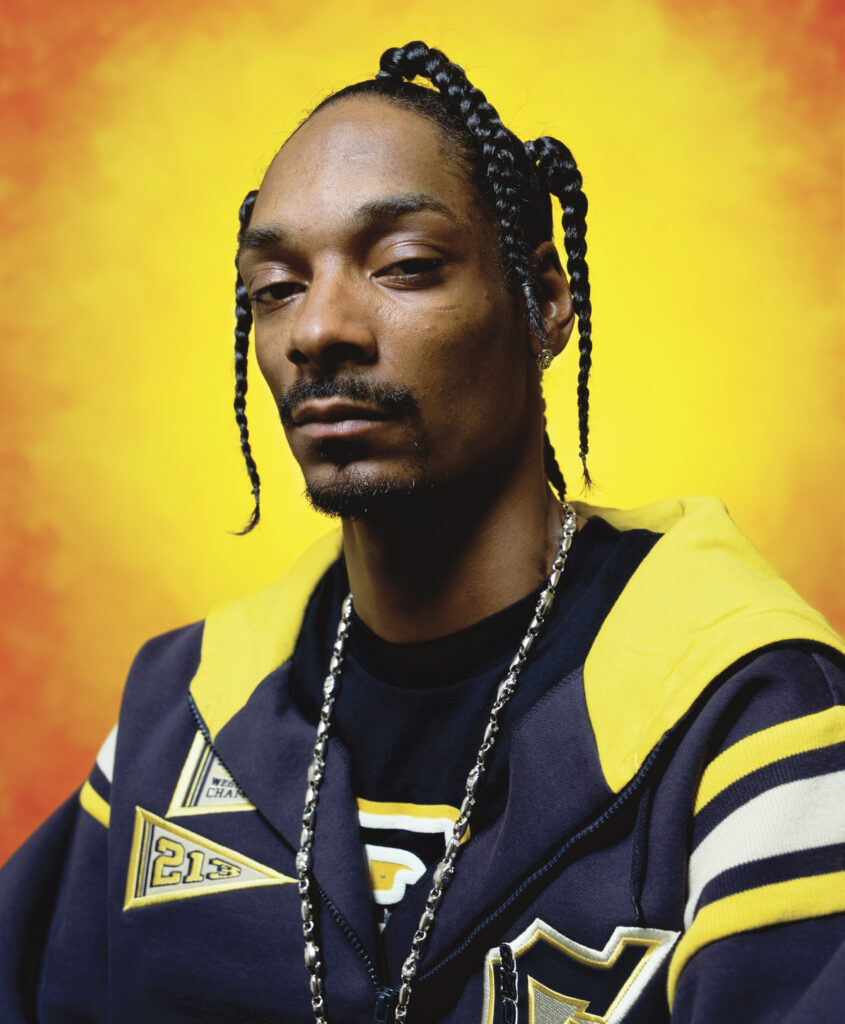

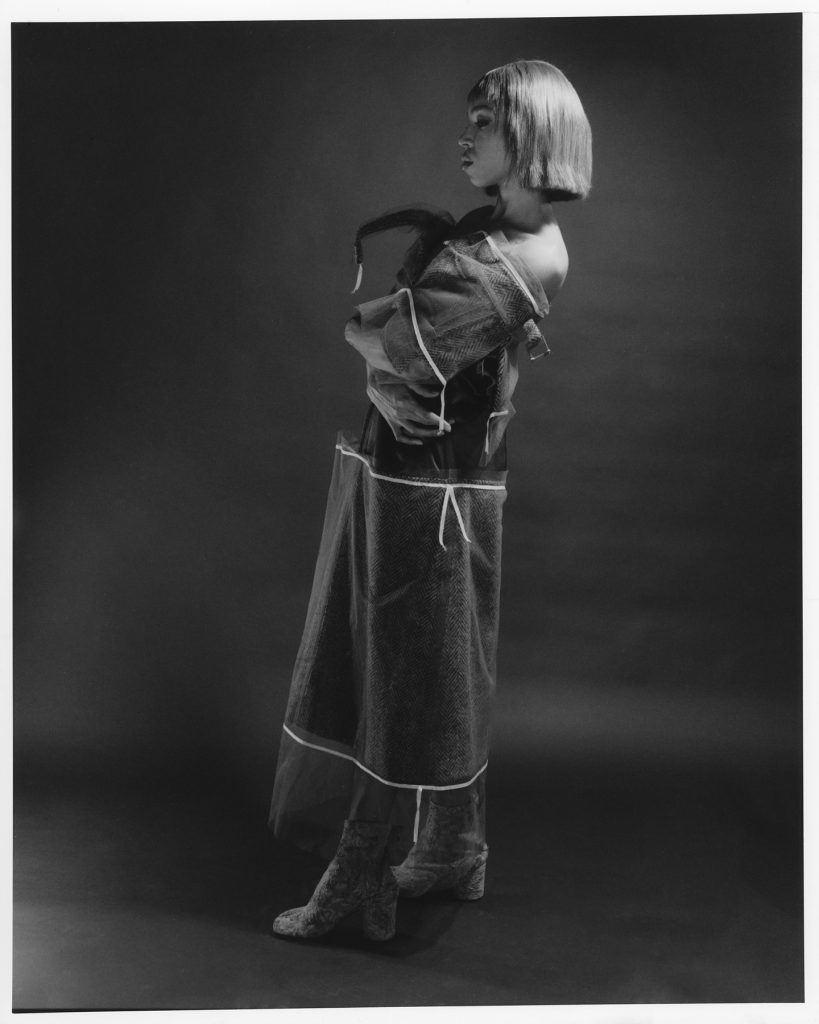

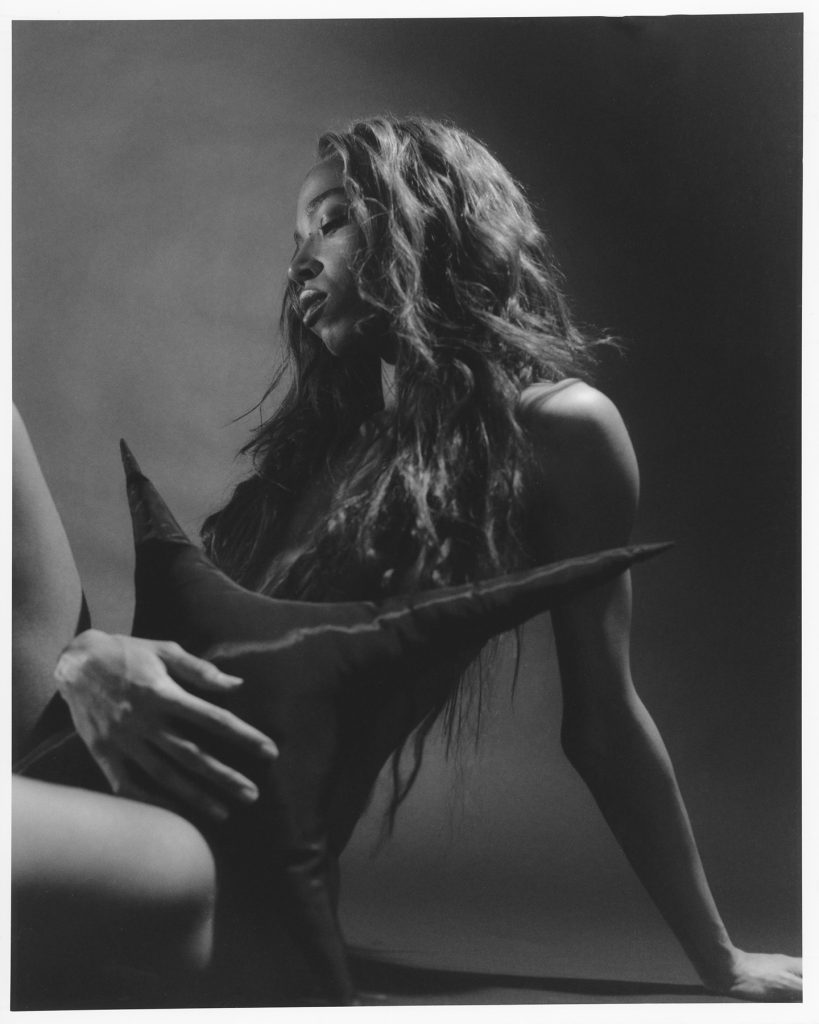

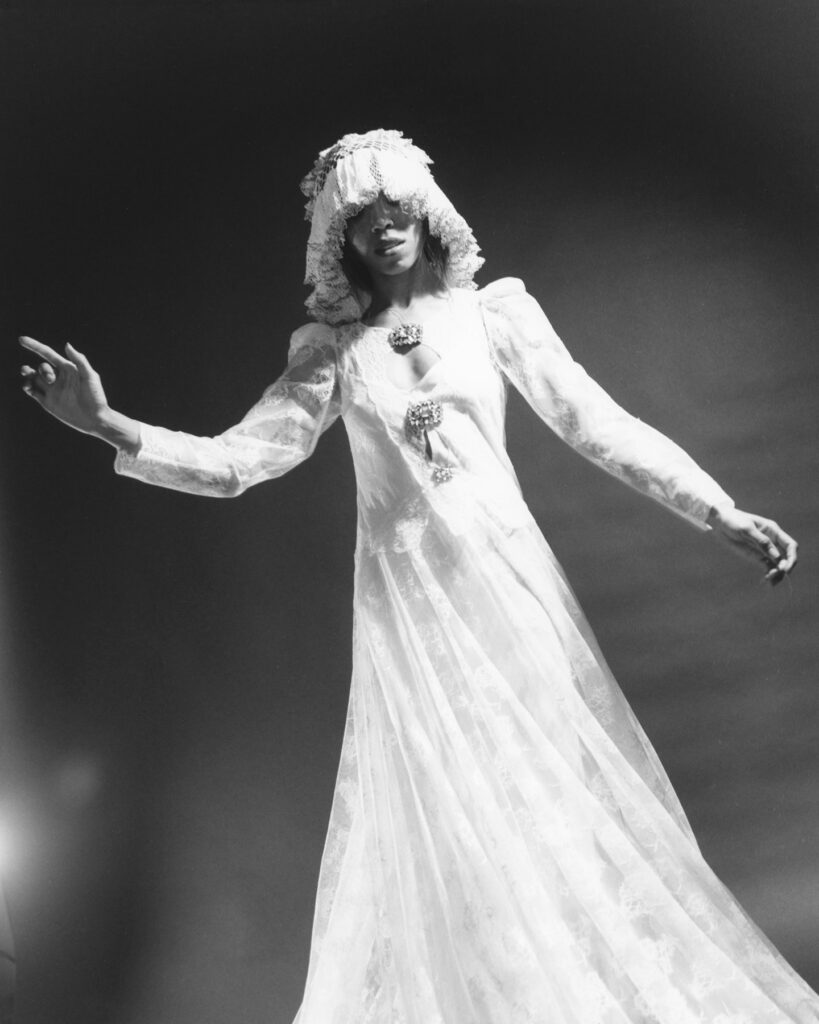

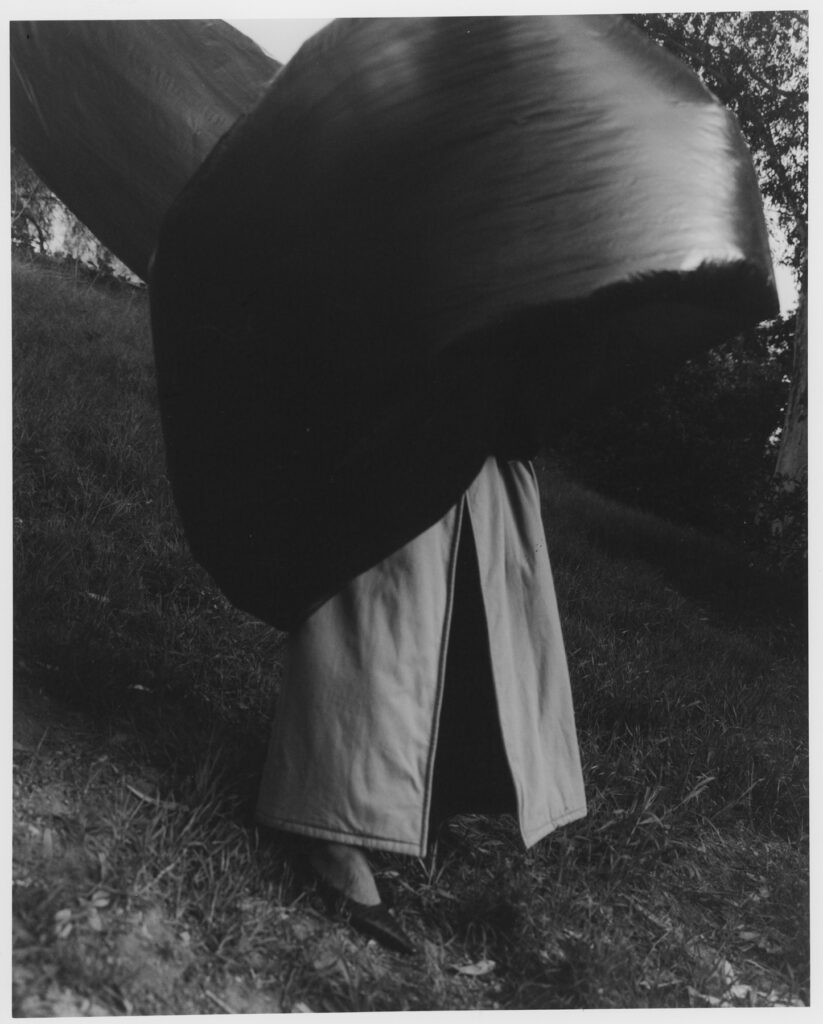

Photography · Oli Kearon

Fashion · Kamran Rajput

Grooming· Daniel Dyer

Photography Assistant · Nic Roques

Fashion Assistant · Elza Rauza

Special thanks to Abigail Jessup, William Aspden at XL Recordings and Jon Wilkinson at Technique PR

Designers

- Left to right, jacket NORSE PROJECTS and hat Talent’s own; jacket SAUL NASH

- Left to right, jacket and trousers ONTSIKA TIGER and boots ARMANI EXCHANGE; jacket CP COMPANY, trousers TEN C, shoes and cap Talent’s own

- Left to right, full look ARMANI EXCHANGE; jacket and trousers MONCLER and shoes Talent’s own