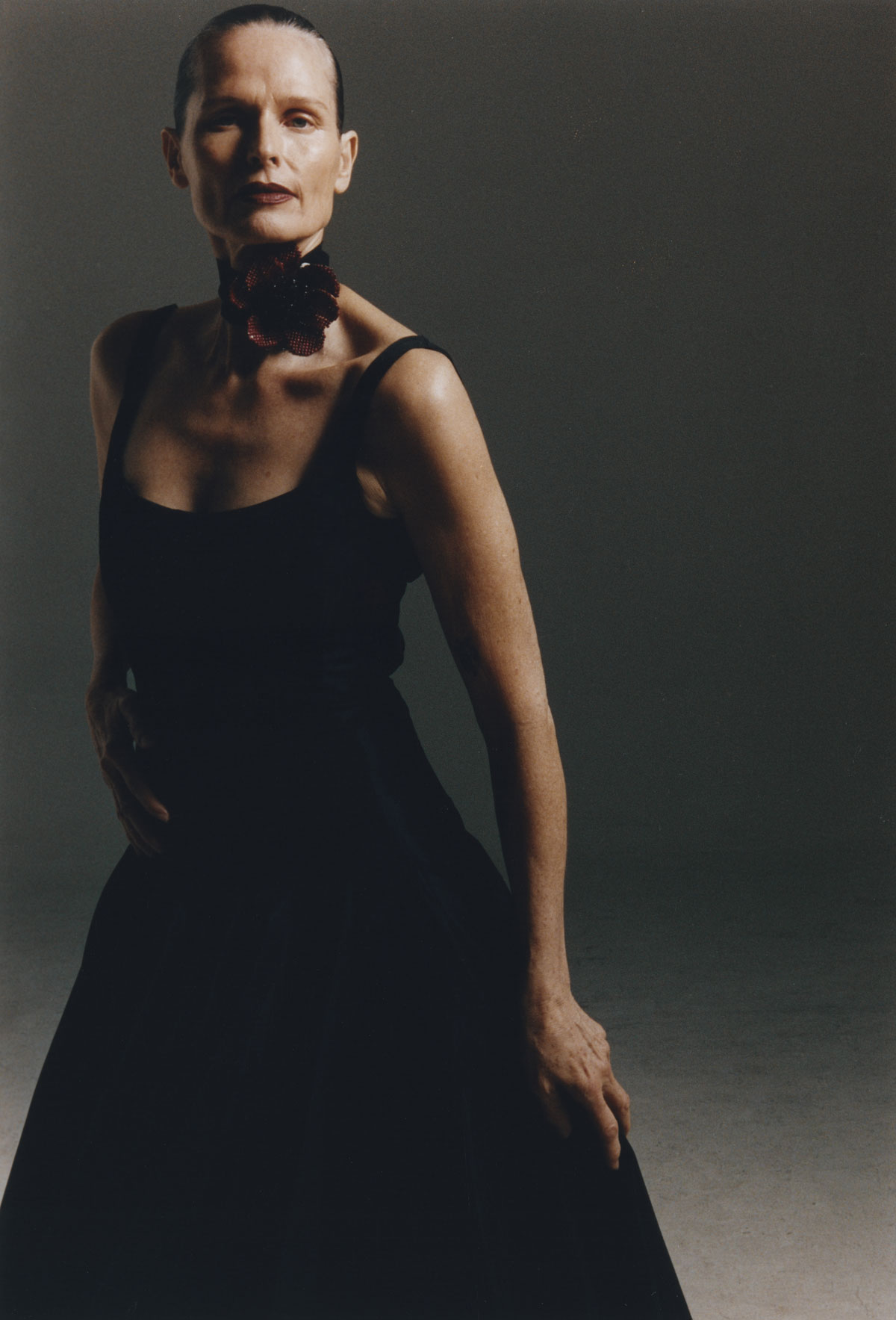

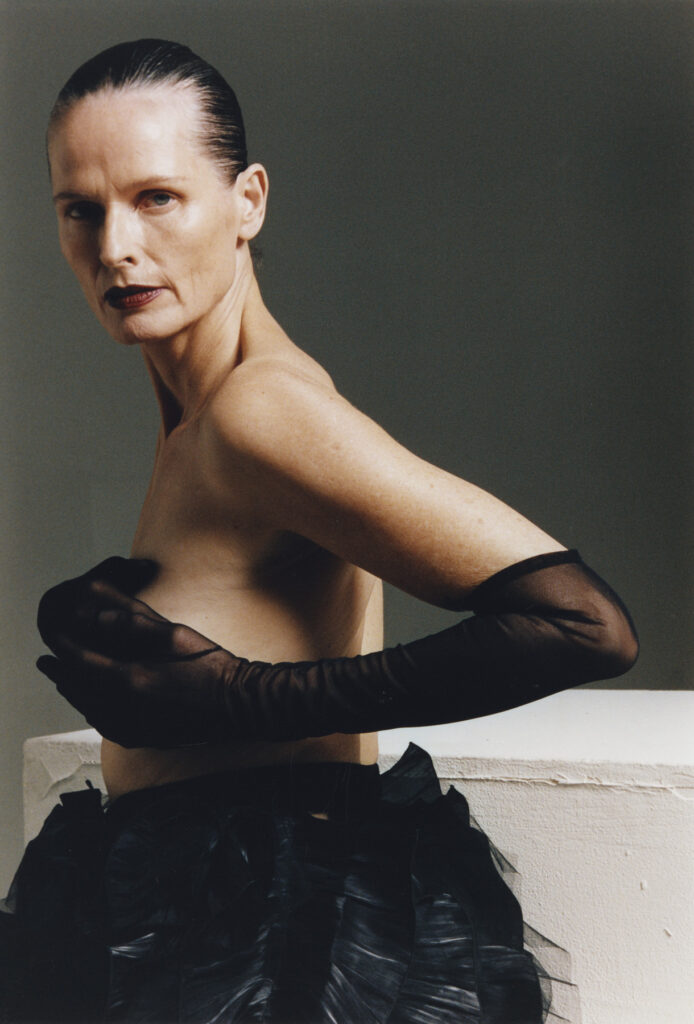

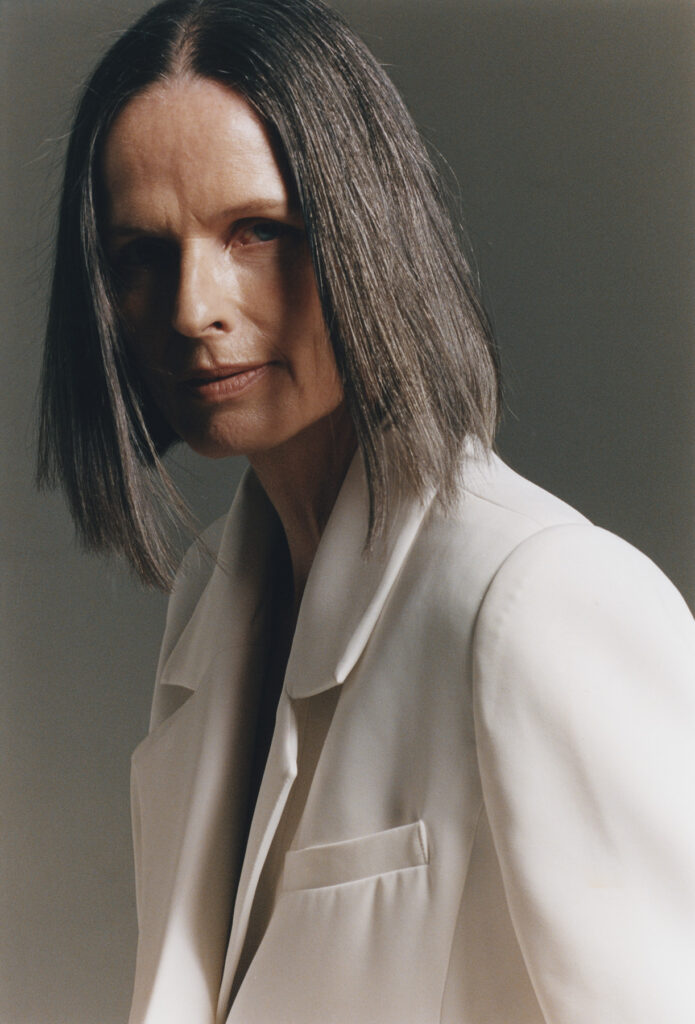

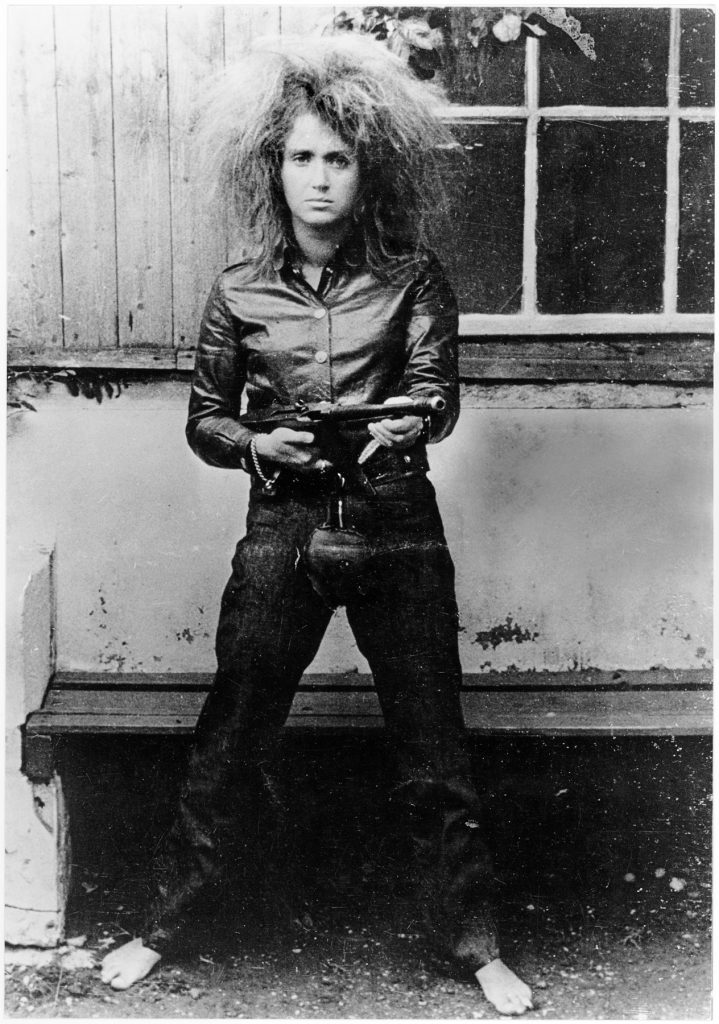

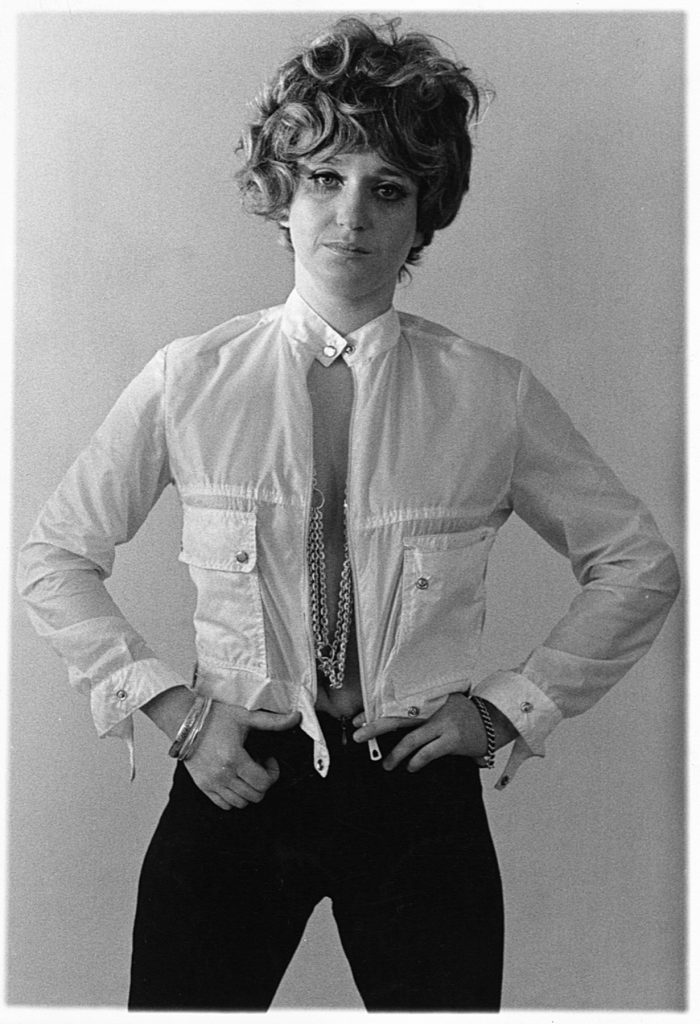

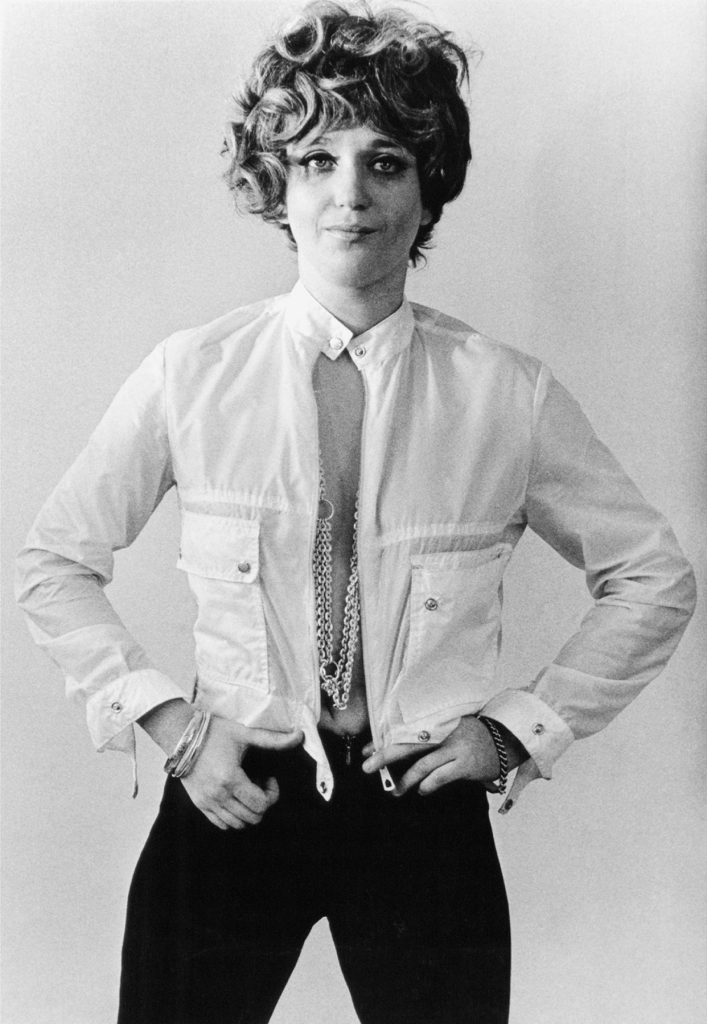

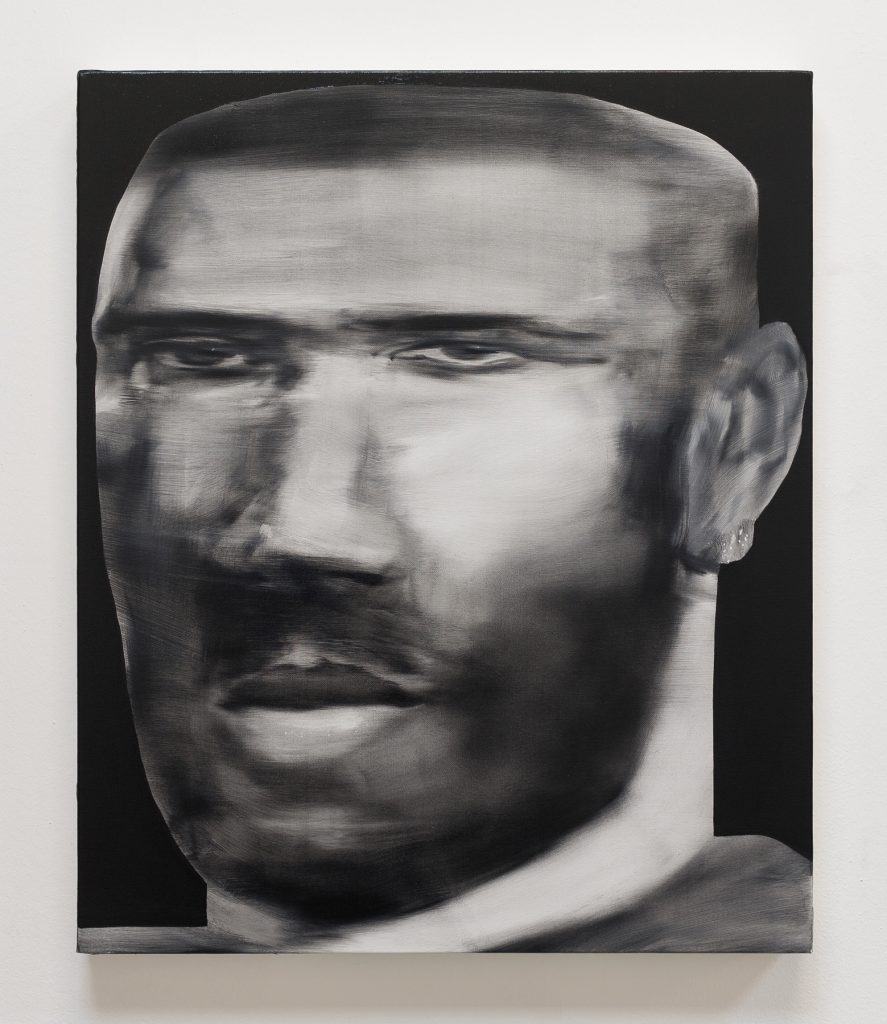

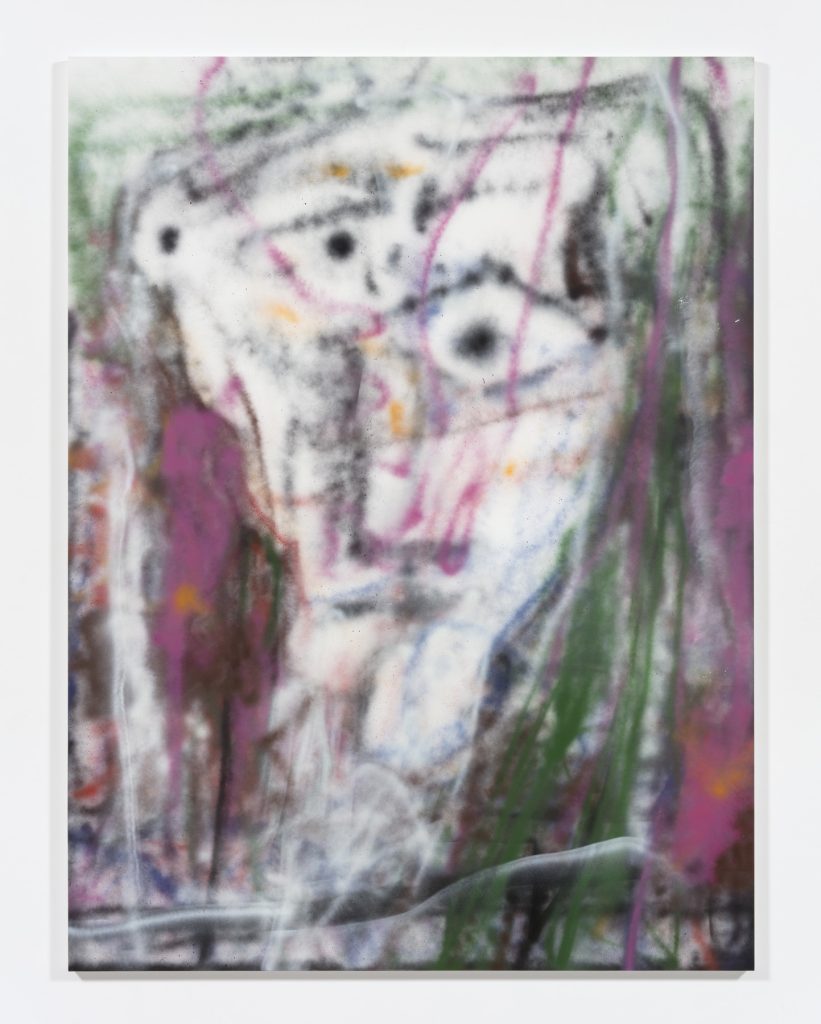

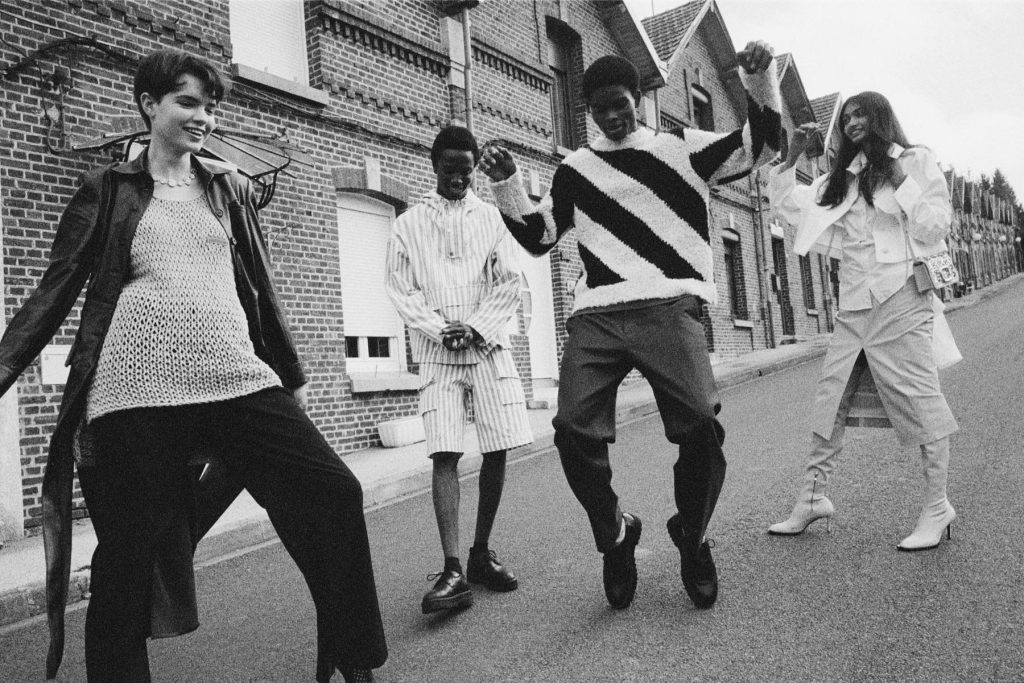

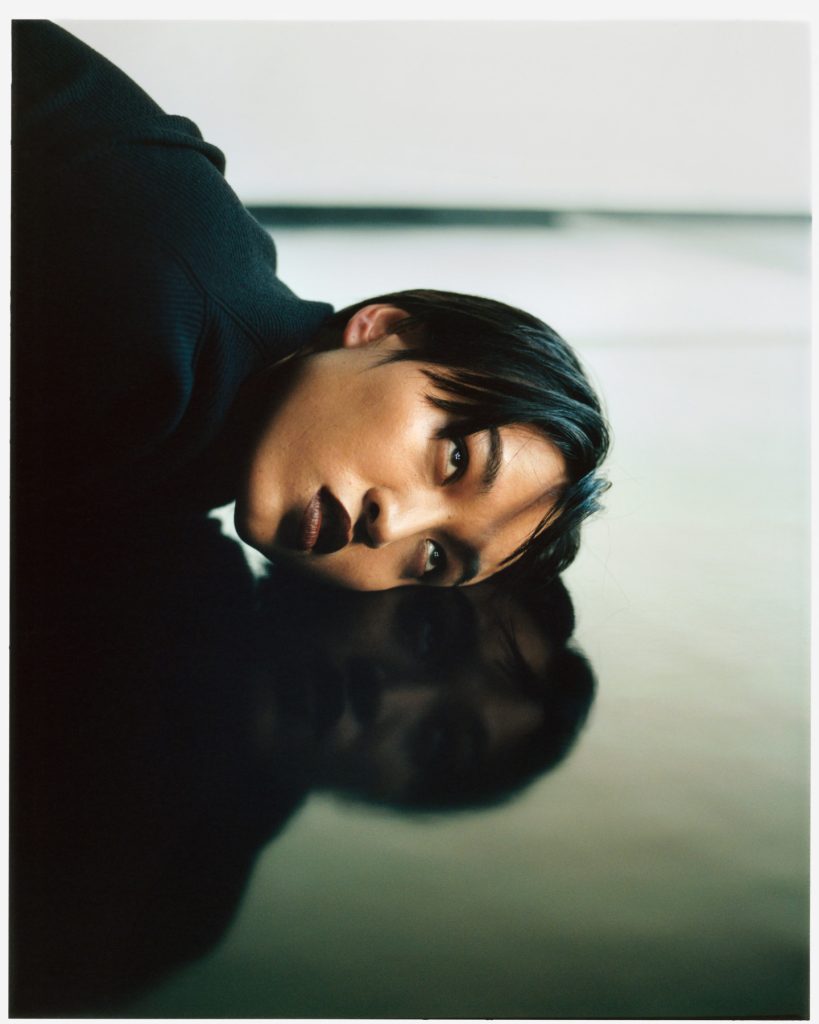

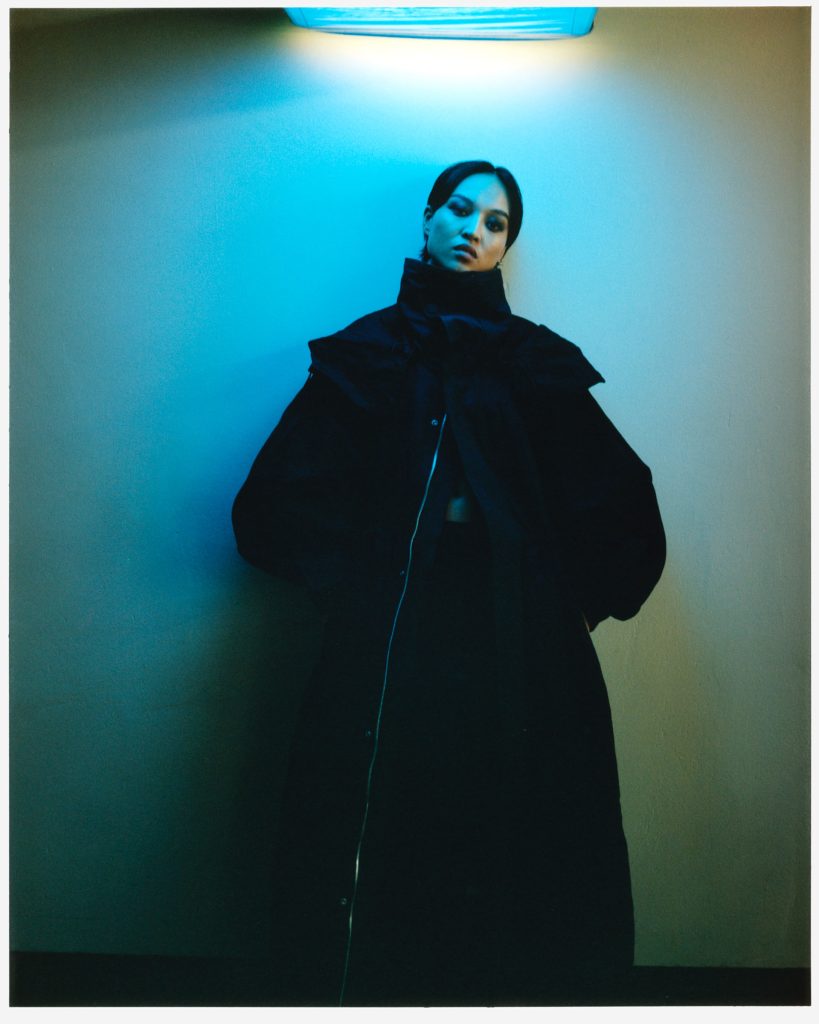

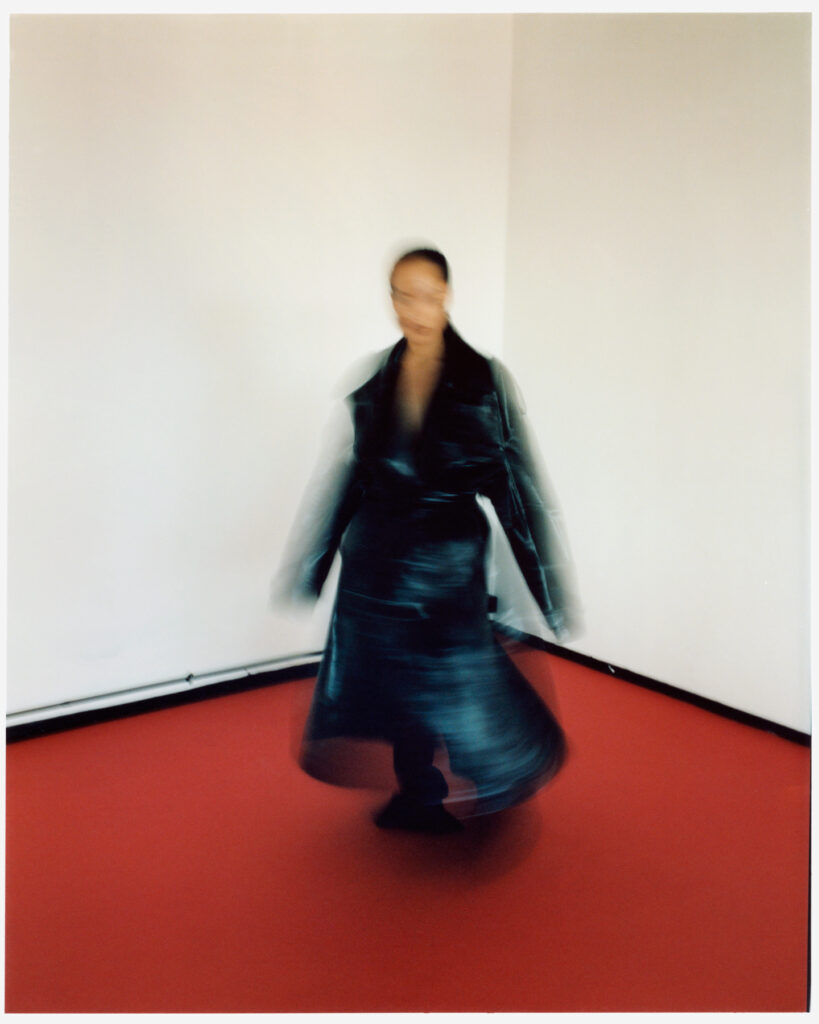

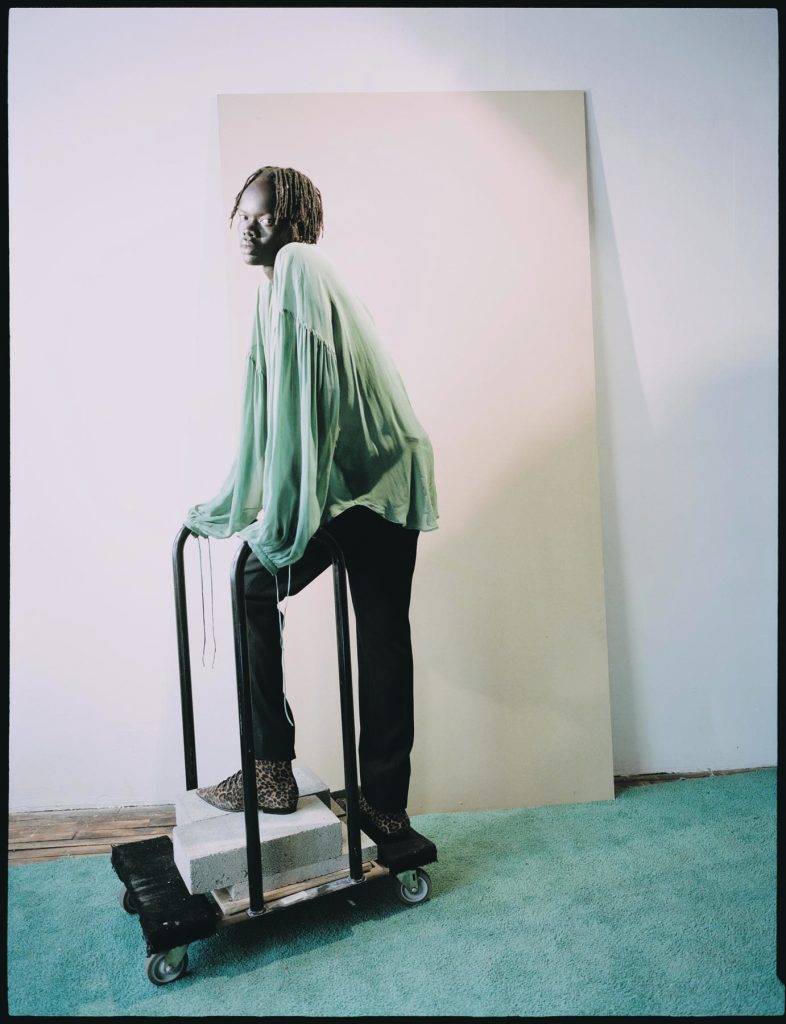

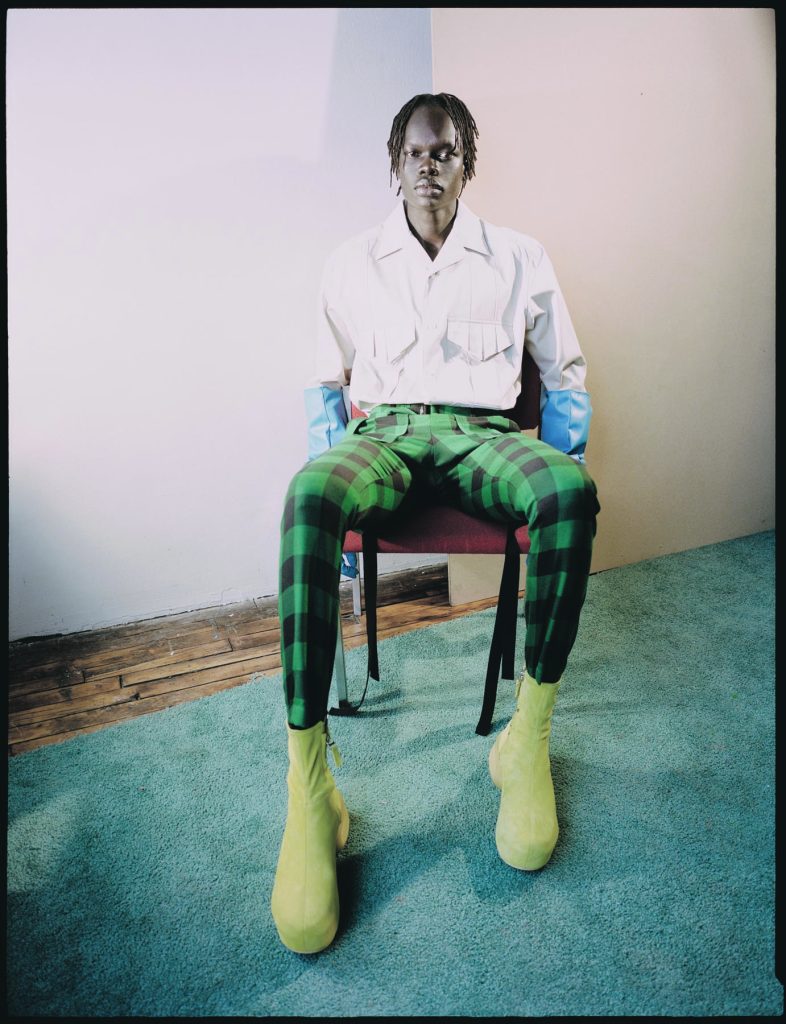

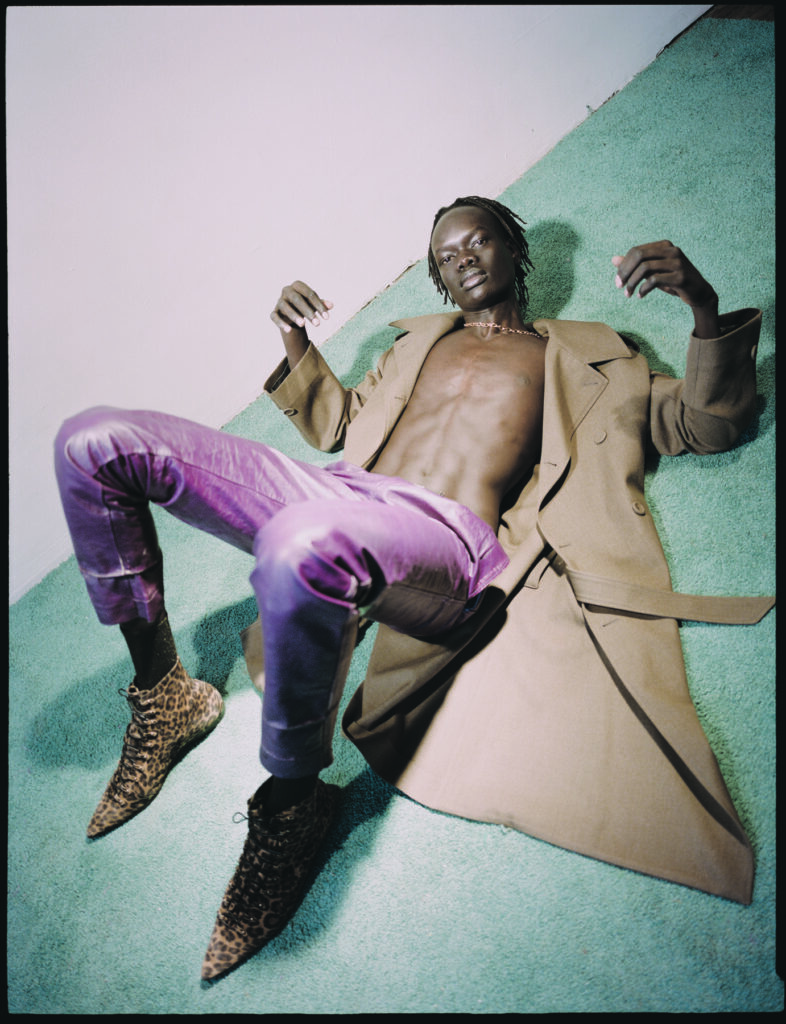

Exploring the ambiguities of life through the rapid shifts the present feels

The first three-dimensional, physical object that multidisciplinary artist Illya Goldman Gubin made comments on the everyday obstacles creatives face in a world dominated by consumerist logic. From the descriptions, several images may come up – glitching computer screens, broken doors, burned bridges, thrashed rooms, or maxed out credits cards – but Gubin built his storyline around an object famed for the hierarchy metaphor: a ladder. “The sculpture is a physical manifestation of the internalized struggle to climb the proverbial social ladder, our personal hopes, dreams, and challenges manifesting in a sculpture of rough materiality,” says the artist. Soon, viewers will find out the interconnectedness of everything Gubin works on.

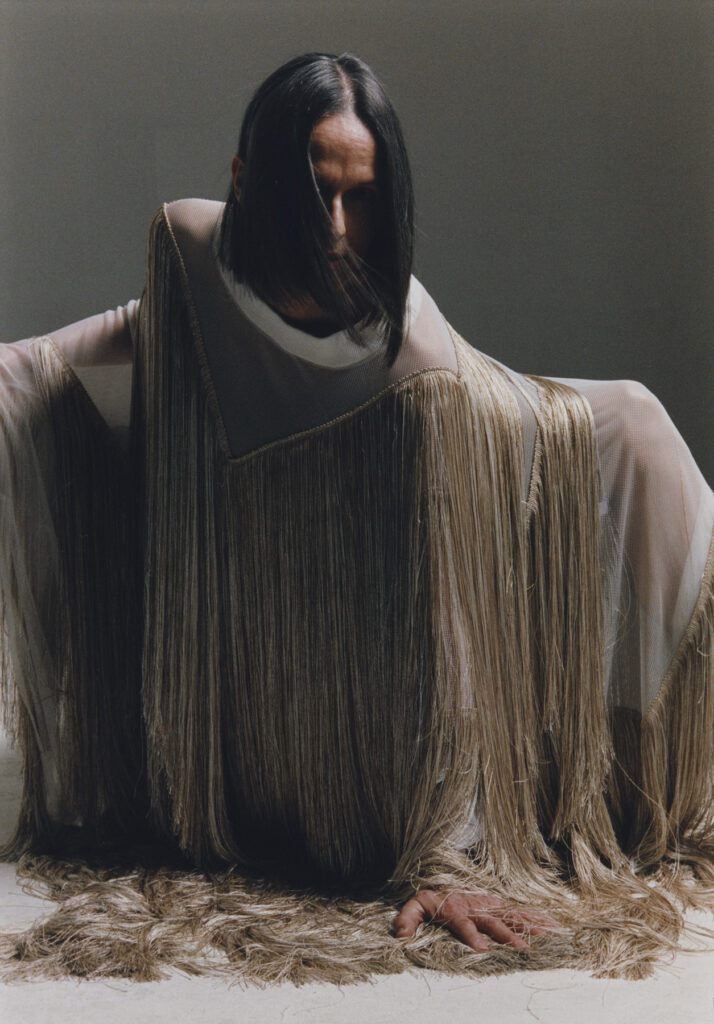

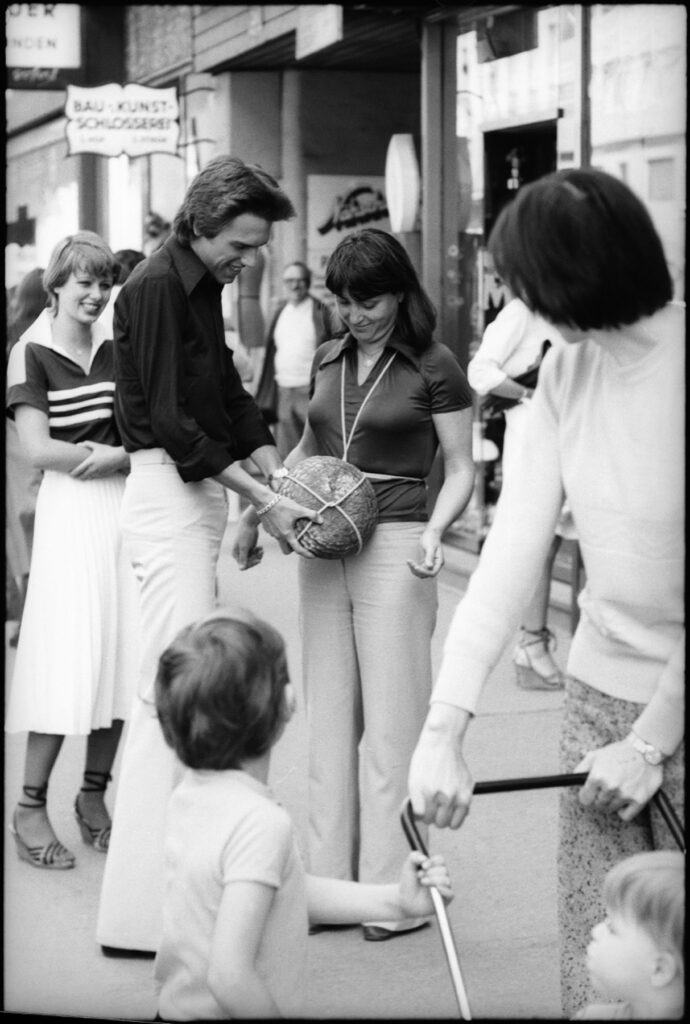

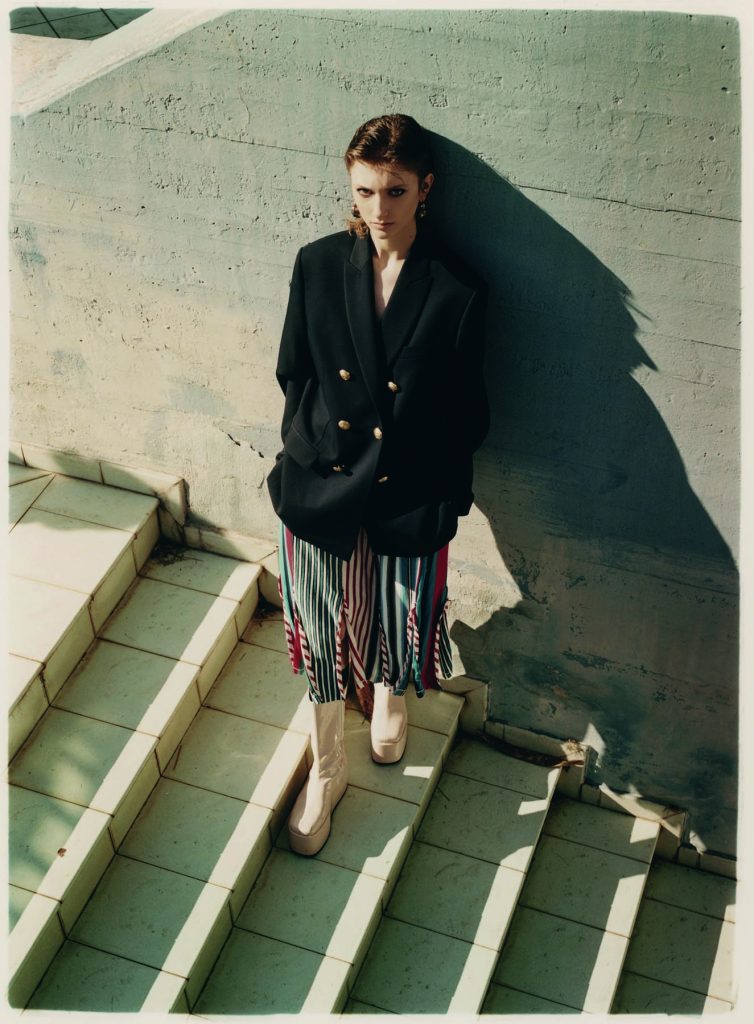

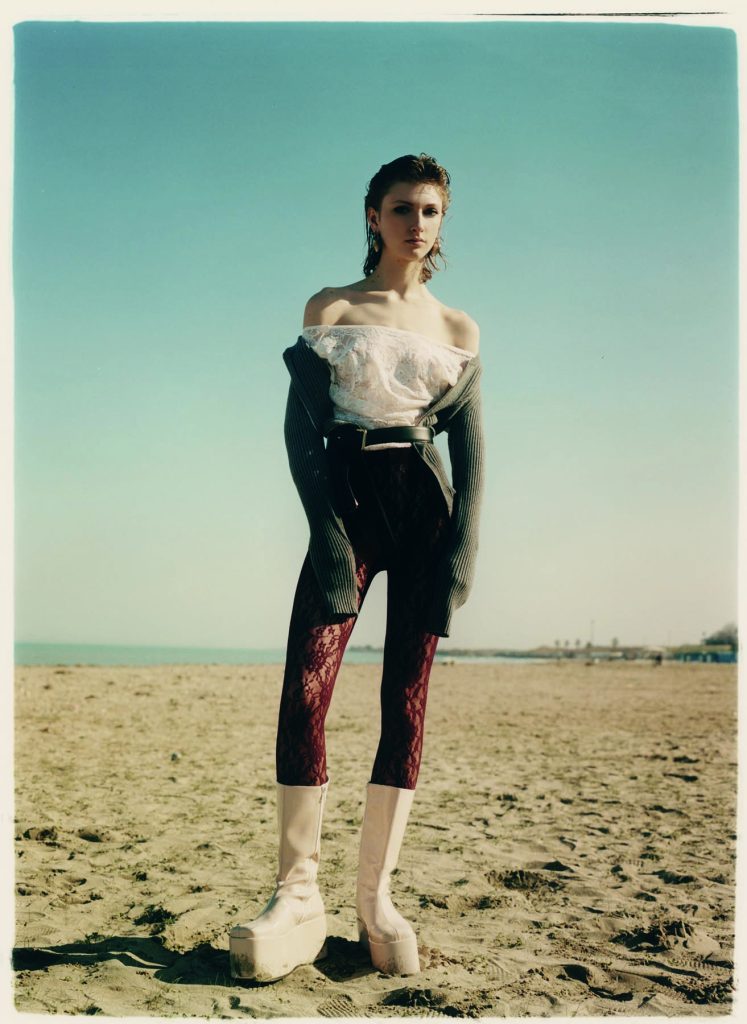

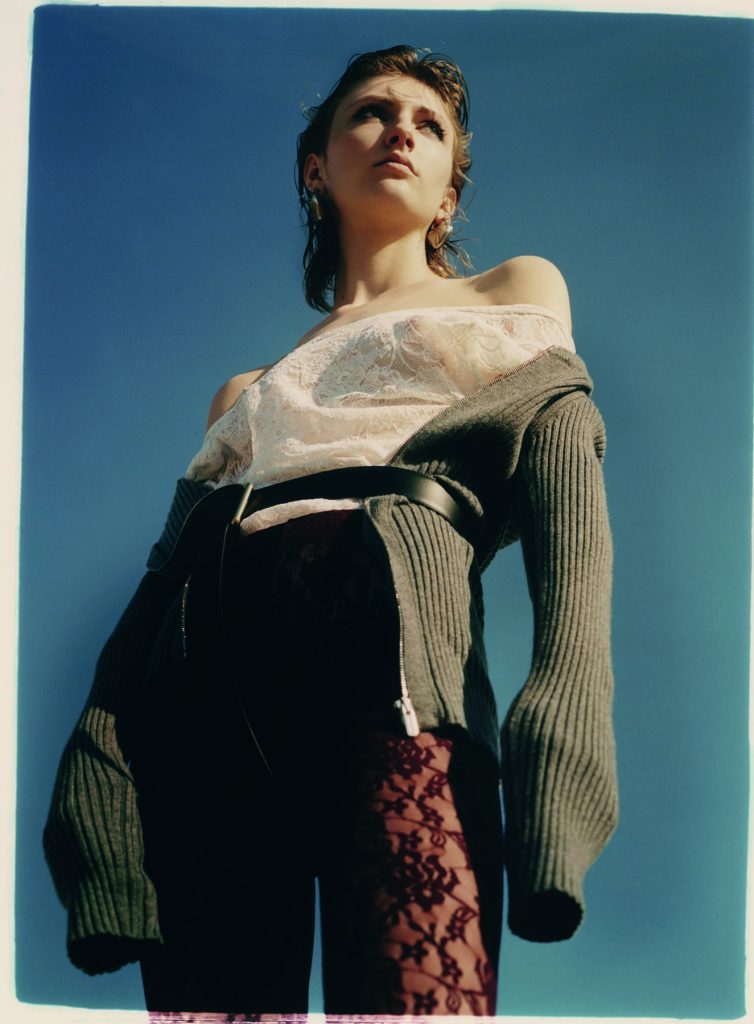

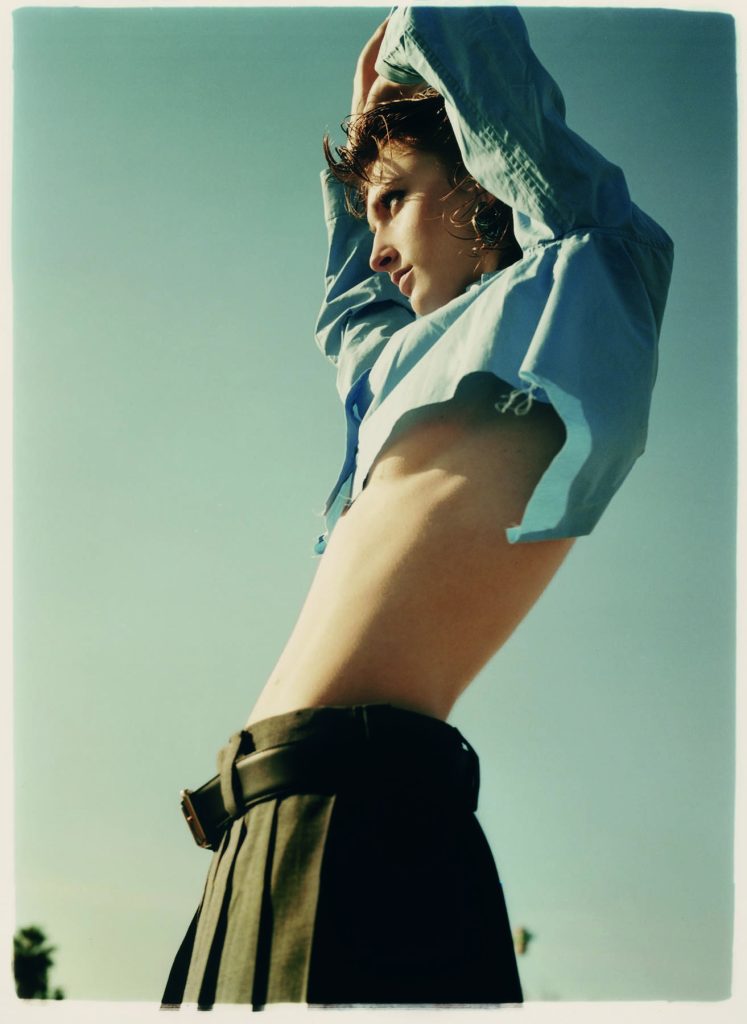

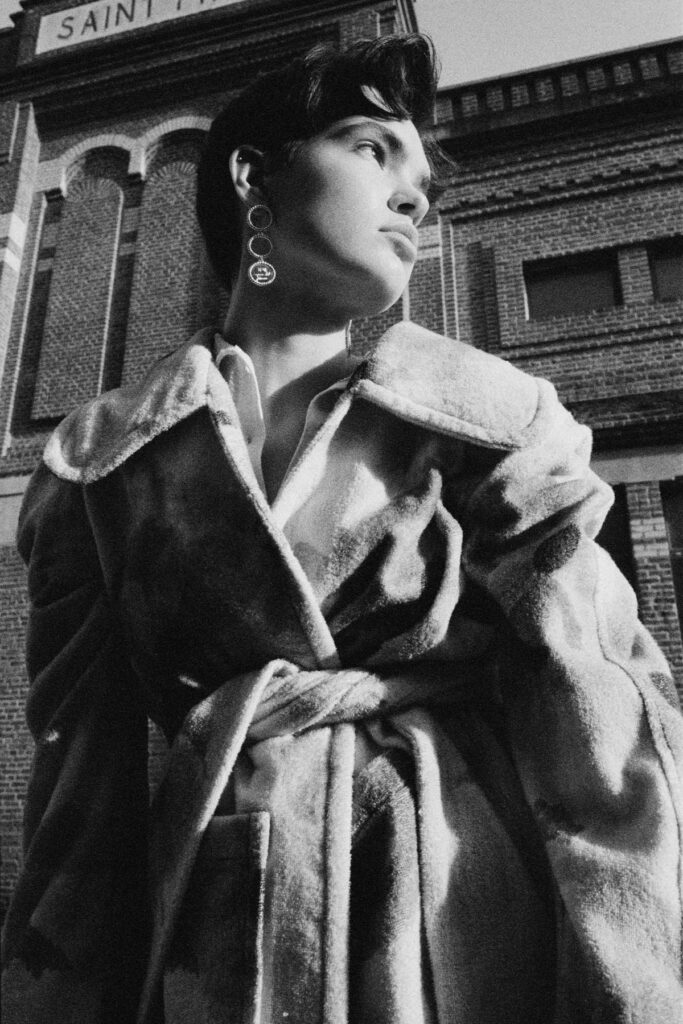

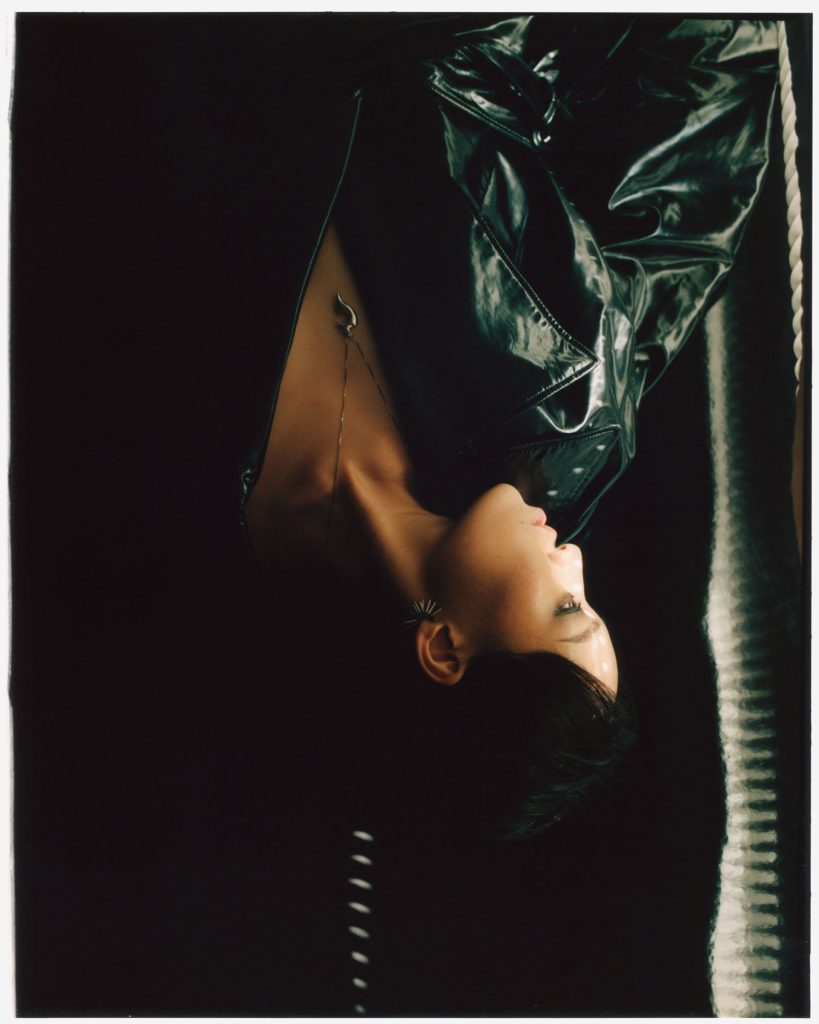

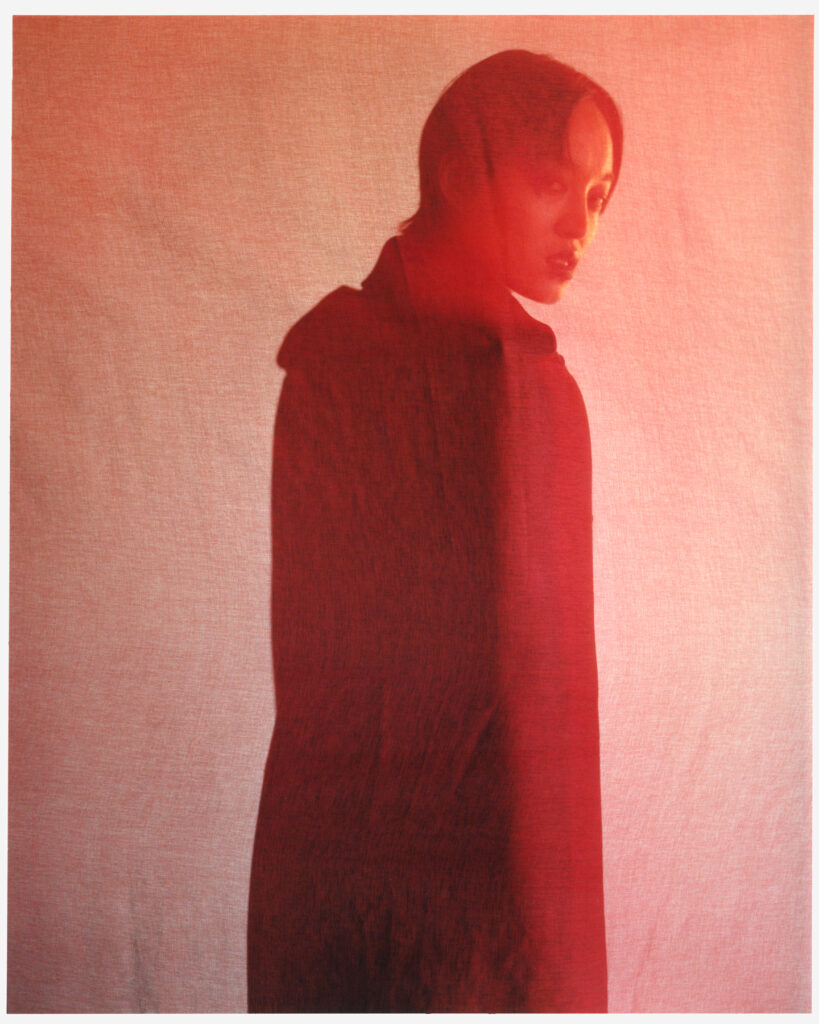

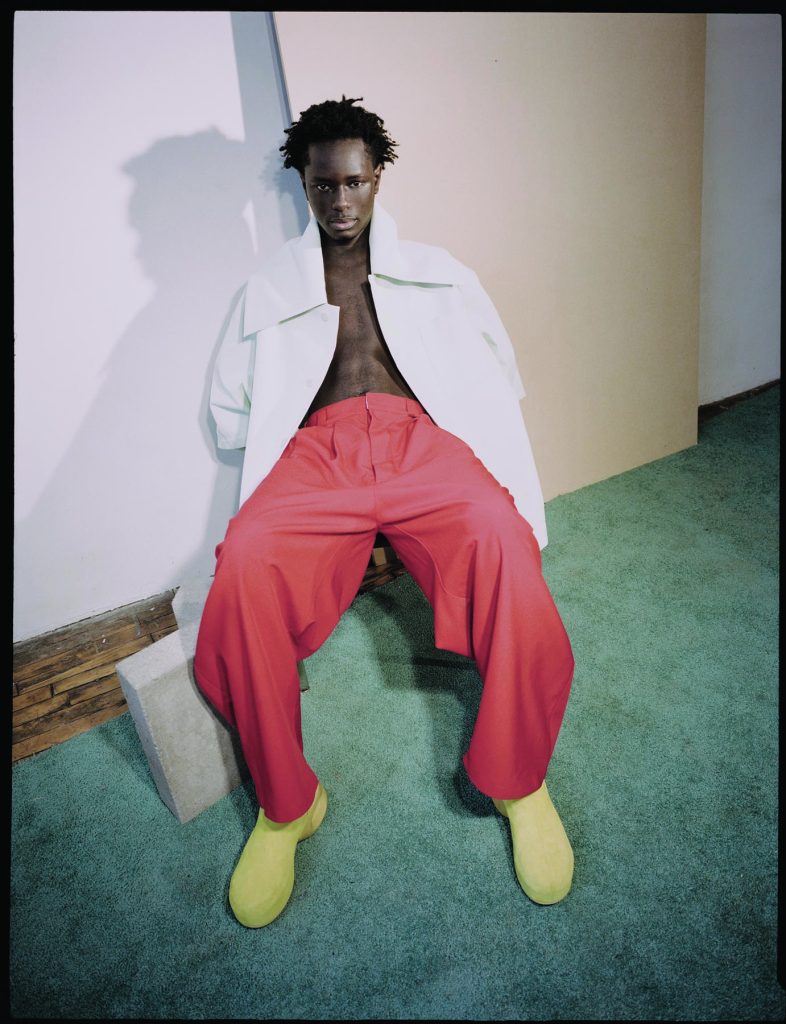

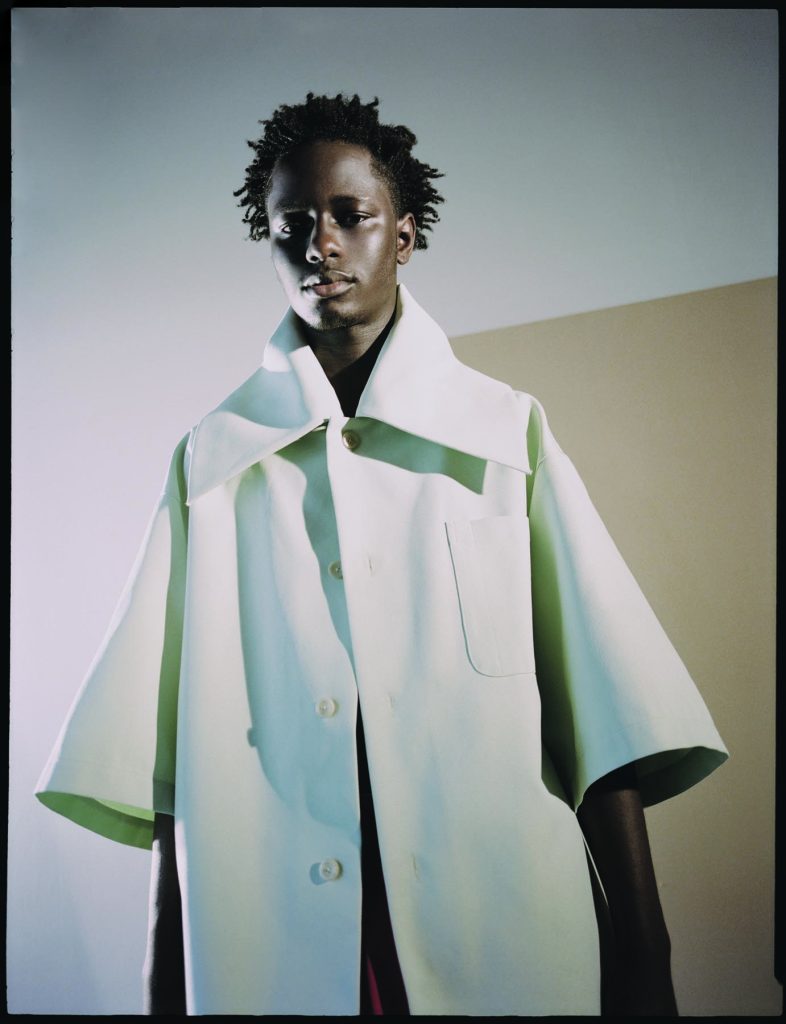

An atelier and an art shop define the homes of Gubin. The first sees the continuation of his artworks, a deviation from a fashion line or merch and a journey towards works of art created from works of art. “The greed for a dialogue between clothes and artworks becomes a study. The clothes are created with the Japanese idea “Ichi-go, ichi-e”. This means ‘One Time, One Meeting’ which reminds us of the ephemeral nature of everything around us,” the brand states. It lies upon the idea that one can never dip their toes into the same lake twice as the water flows – always moving, never settling.

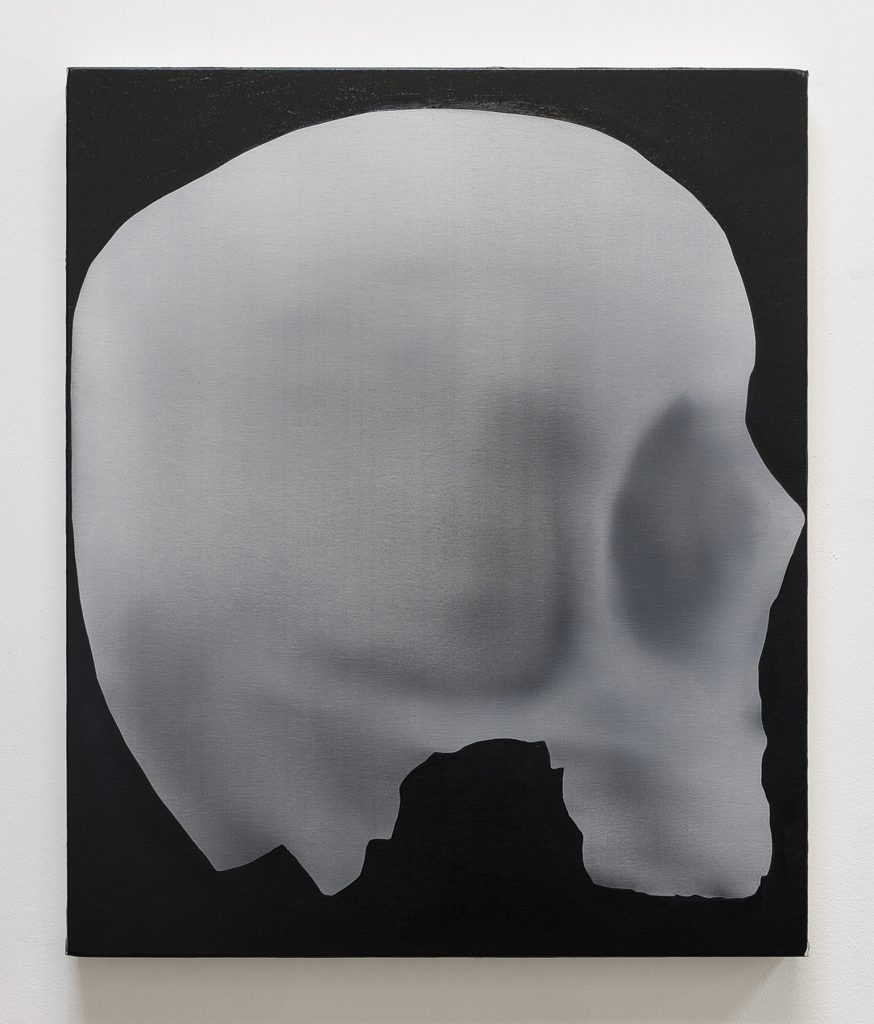

From this ethos, the atelier comes to life. It breaks the binary continuum of thinking and feeling, science and mysticism, tradition and innovation, handmade and luxury goods, and perfection and imperfection. Gubin’s installations underline the complexity of human consciousness to unearth the depth of self-understanding. He borrows terms from Judaism and infuses them into his words, serving as reminiscences to the cultural imprint. For the artist, the culmination of multiple perspectives, fused with self-reflection, gives birth to a realm of new sanity, a marriage between codes of the past and newly acquired knowledge.

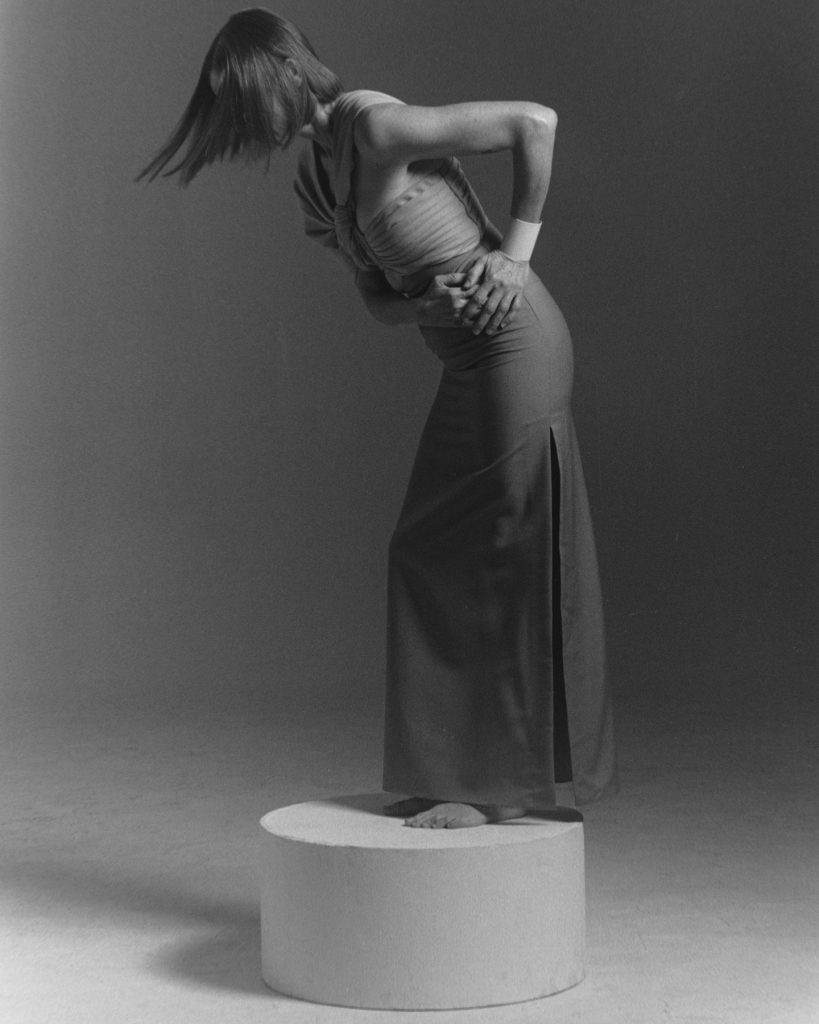

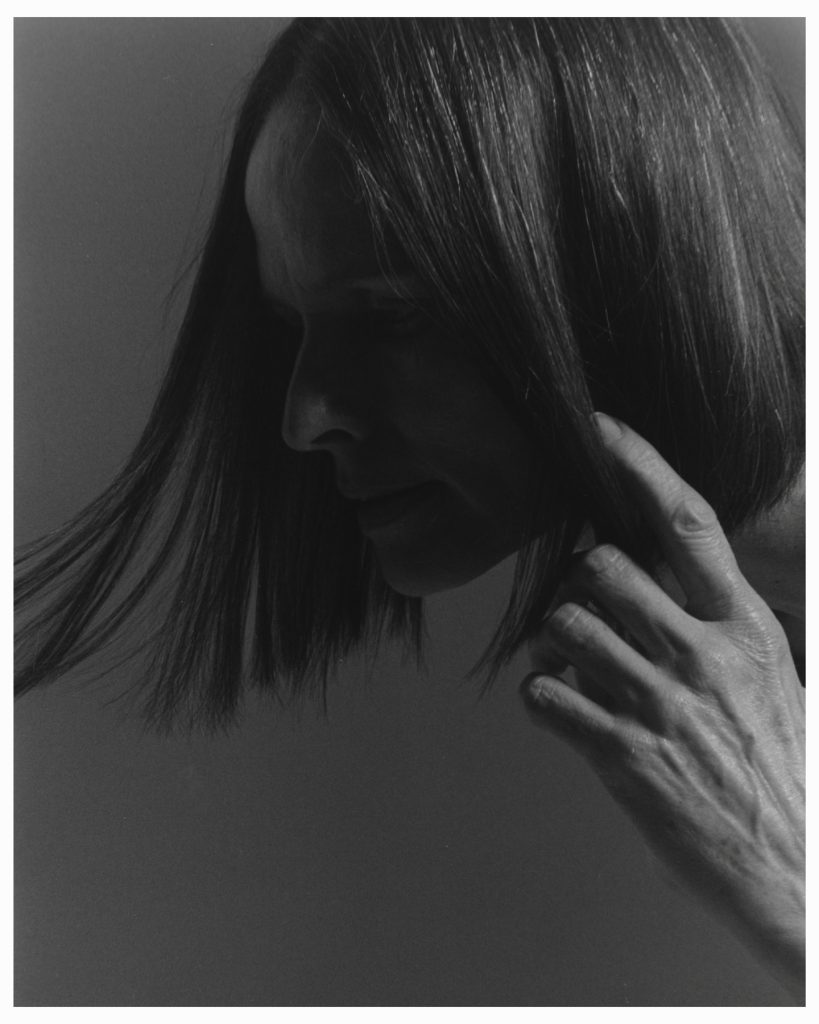

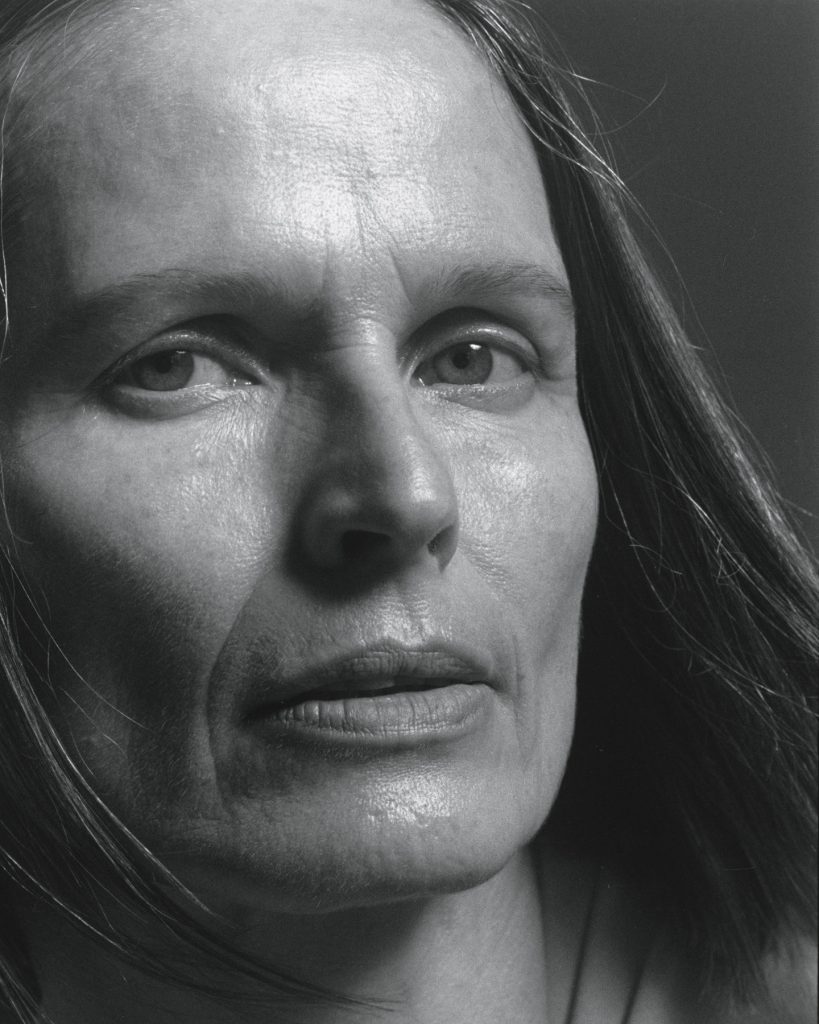

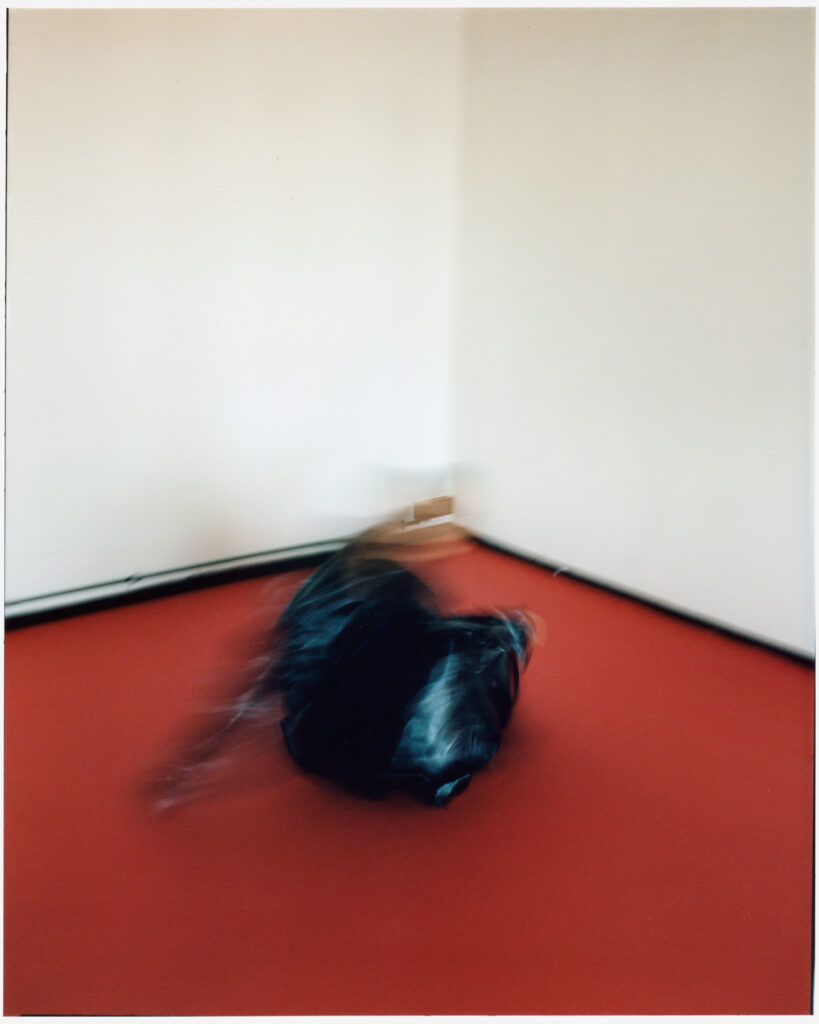

Gubin not only explores the ambiguities of modern life, challenged by the rapidly shifting conditions of the present, but also creates multi-layered reflections of everyday perception. He transforms paradigms, materials, space, and time into works that usher the audience into a sensorial experience, an invitation to think, feel, see, hear, and meditate. From that cocoon of meditation, Gubin captures the zen and essence of perpetuity and mold them into sculptures, canvasses, furniture, bags, bowls, t-shirts, lamps, soils and so much more. His body of works remains in a constant state of flux, moving in and out of the spirit to understand the self, to open the mind and heart, and to liberate one’s spirit.

For NR, he celebrates his voice and visions as a multidisciplinary artist through a tone he knows best: poetic, philosophical, polished, and pragmatic.

NR: Where and how did your fascination with “breaking the binary continuum of thinking and feeling, science and mysticism, and blurring the line between tradition and innovation, handmade and luxury goods, perfection and imperfection” start? What personal experiences nudged you to found I G G?

IGG: It started from questioning my inner self and finding answers in different areas and philosophies. I wanted to bring ideas and questions together. I wanted to start an open dialogue.

“It is all done for energy and the closeness to the earth.”

Your atelier is divided into an art shop and a catalog. Starting with the art shop, you reiterate that “it is not a fashion line or merch, but works of art that are created from works of art.” Is there a reason you’ve stressed this?

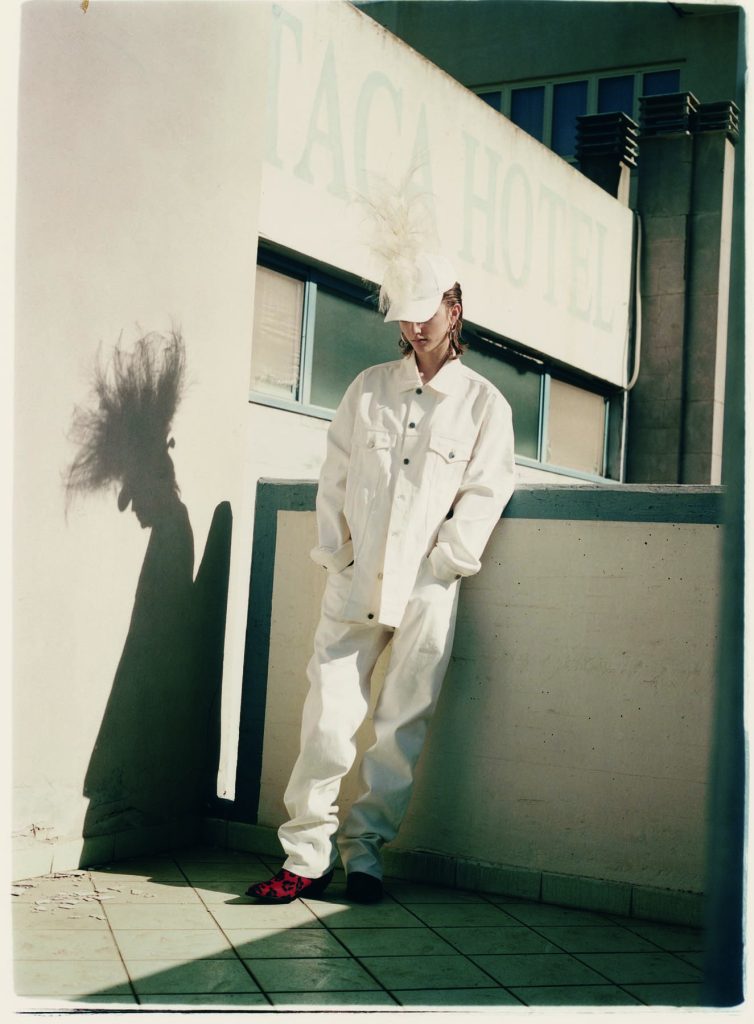

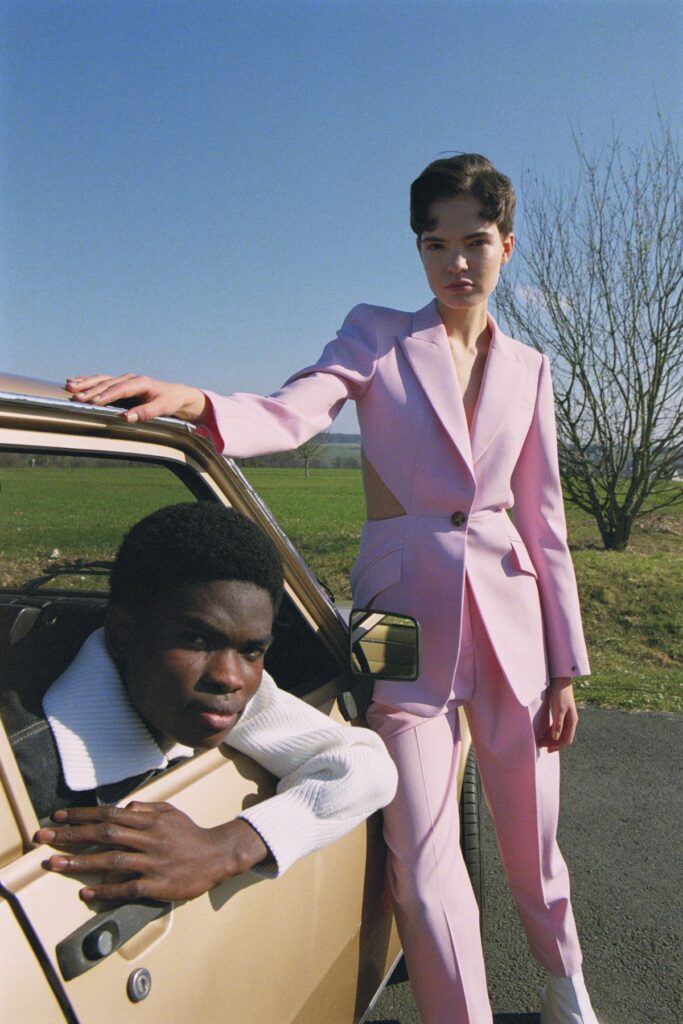

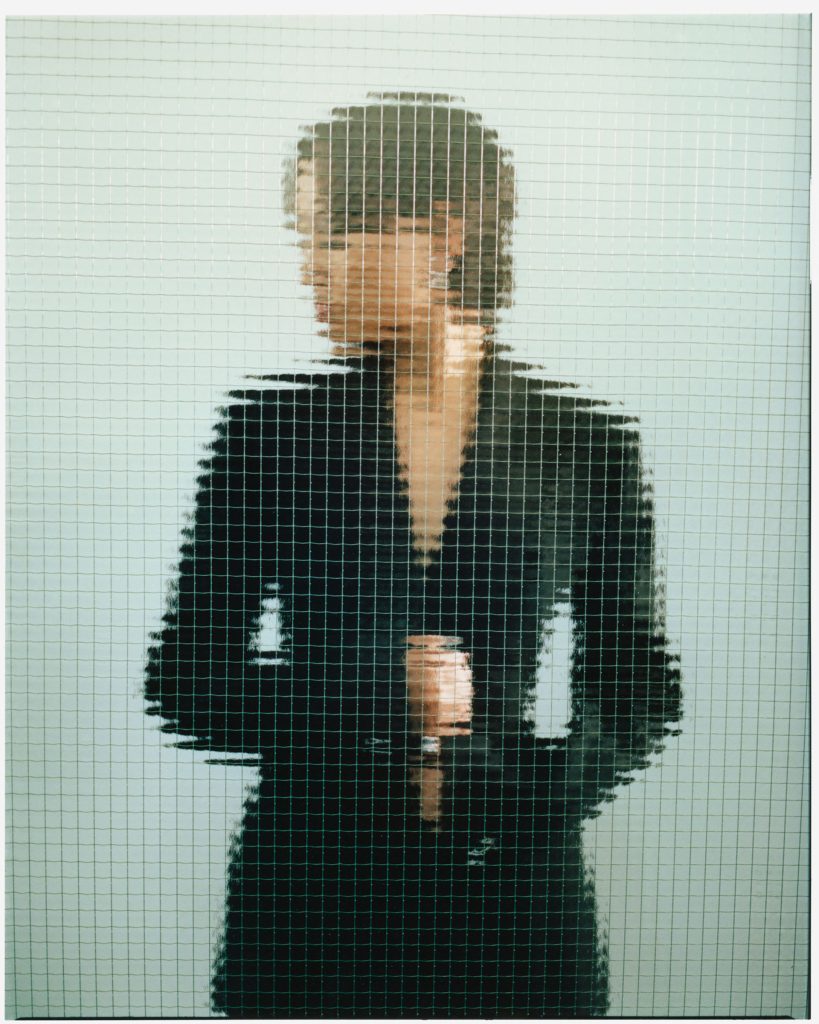

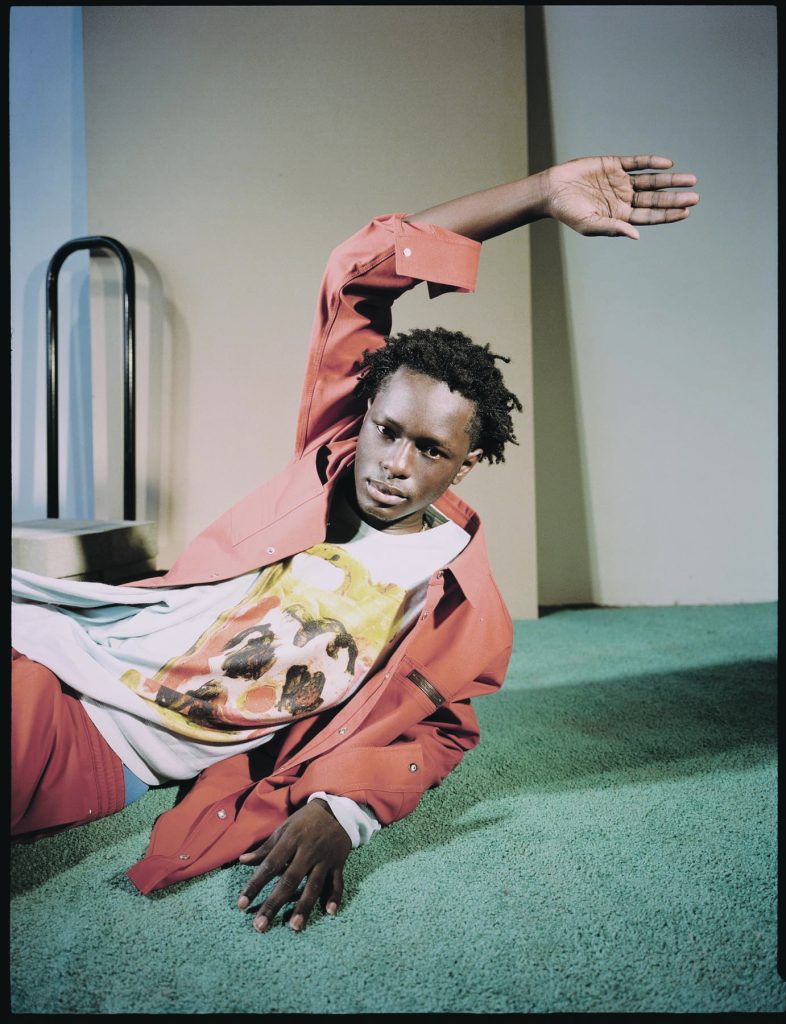

Yes. I try to push the boundaries of a clothing piece by combining and intertwining it with my artistic practice which, as the result, becomes a significant enlargement of my work.

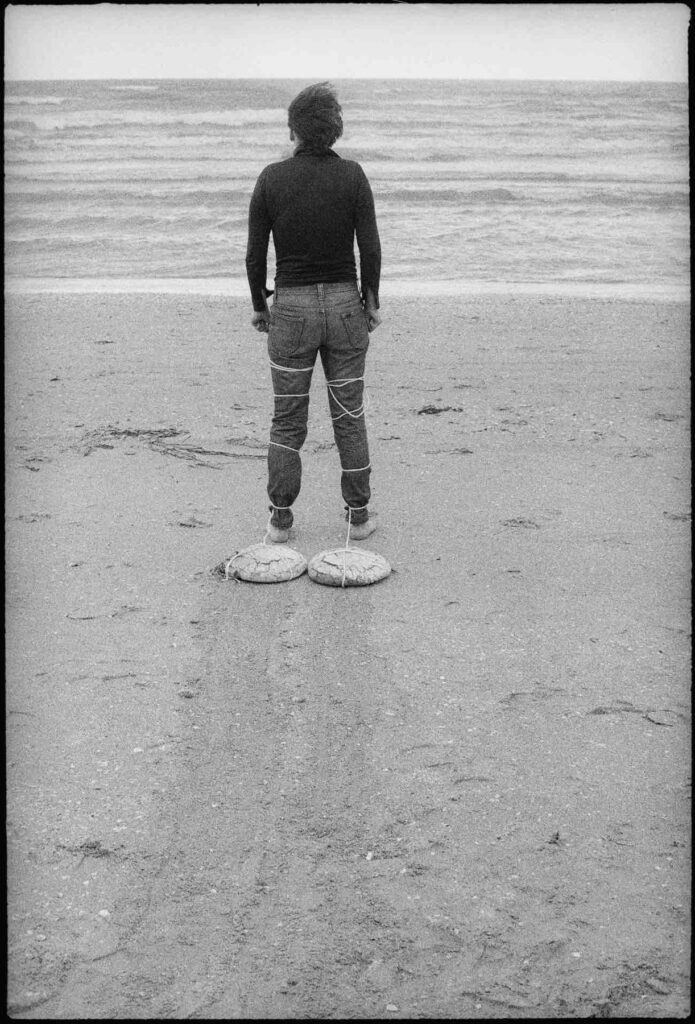

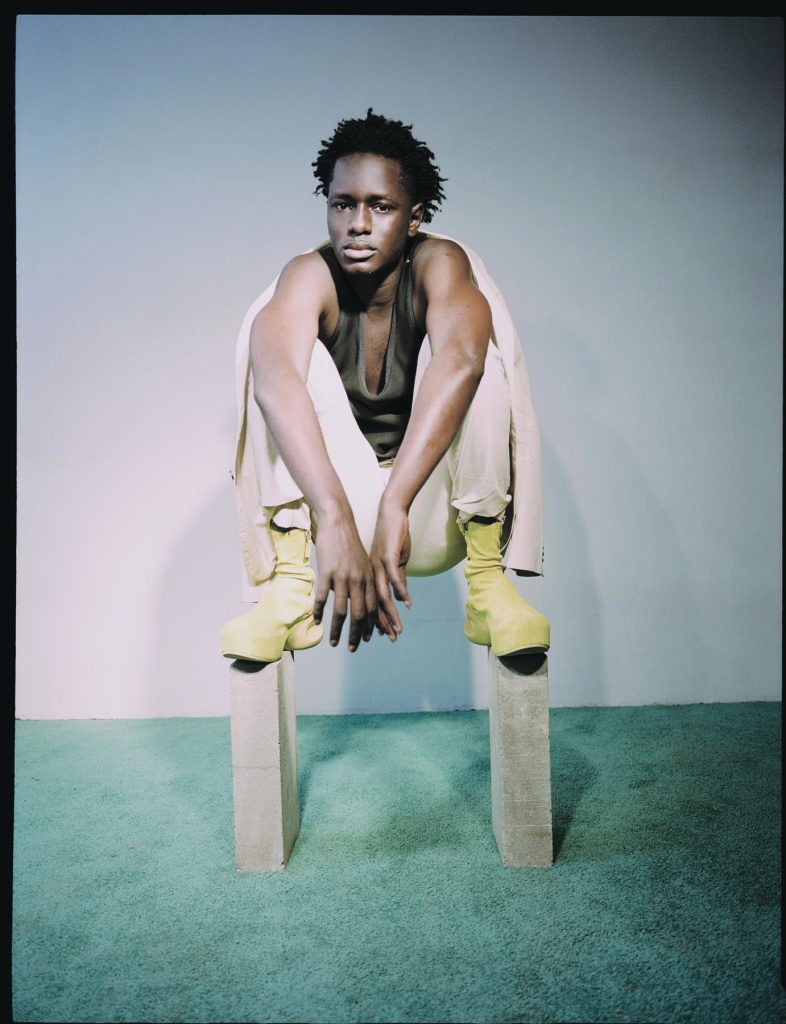

For instance, the surface of the Struktur shoes is ‘hand-worked’ with the same medium as the ‘Struktur’ artworks. Additionally, the shoes are physically attached to a ‘Struktur’ artwork, which has an indirect invitation to be removed by the owner by force. The end result is a state of wearable artwork.

As for your catalog, I am looking at your first project (“Ladder”) and your recent (“Karton Vase”). Between these years, what changes did you make and experience in your artistic, creative, and business style?

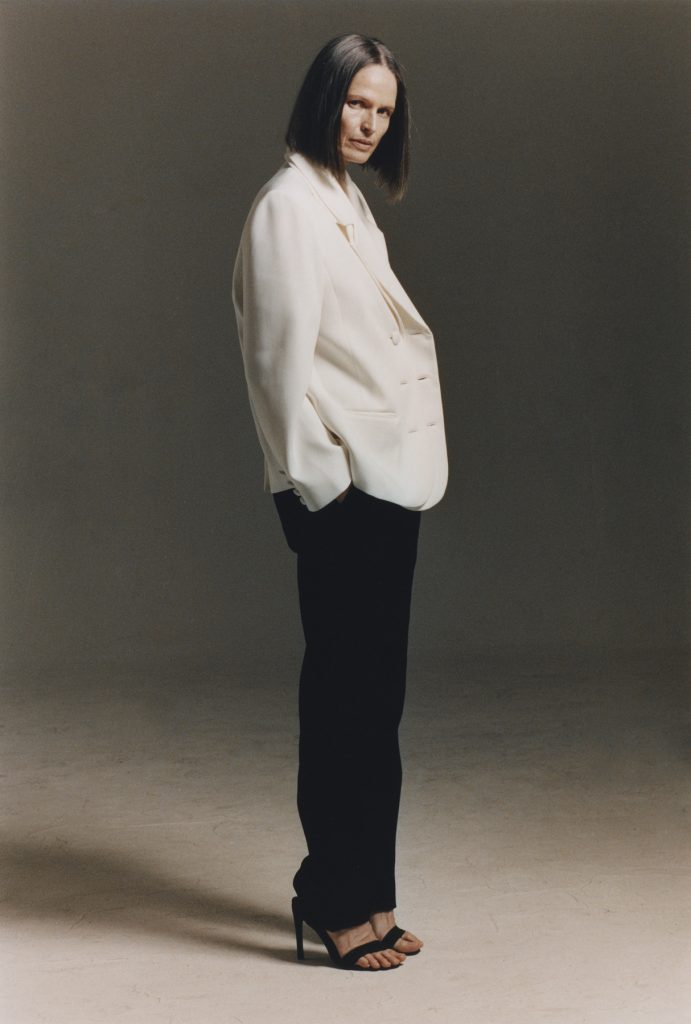

My mind became more balanced. My visions are clearer, and the narratives become more conscious. An artist is a student of his own studies trying to find an answer to a question of one’s personal experience.

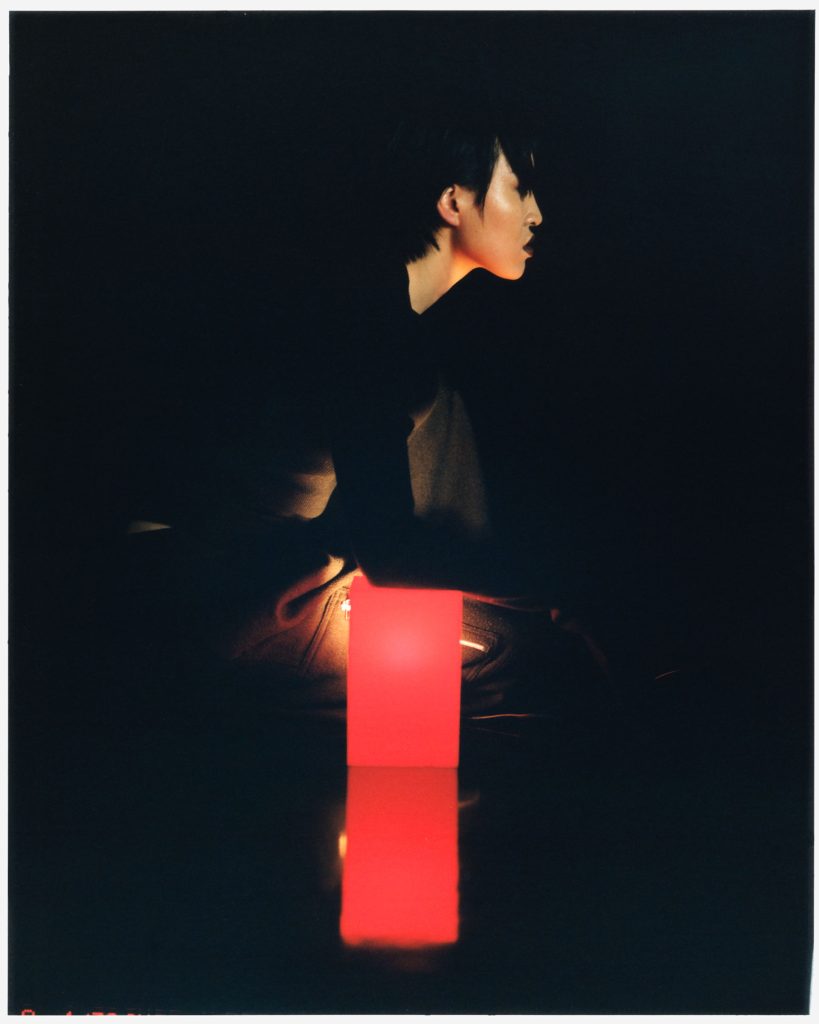

How do you perceive timelessness during the shifting conditions of our present?

My own beliefs, interests, and paradigms are guiding my open-mindedness. Timelessness is still influenced by the Zeitgeist;

“the only difference arises from how you process the flow of information from the observation to the understanding, a contemporary way of thinking.”

Could you share a few projects that resonate well with you, projects that seem to converse with you? What are their backstories?

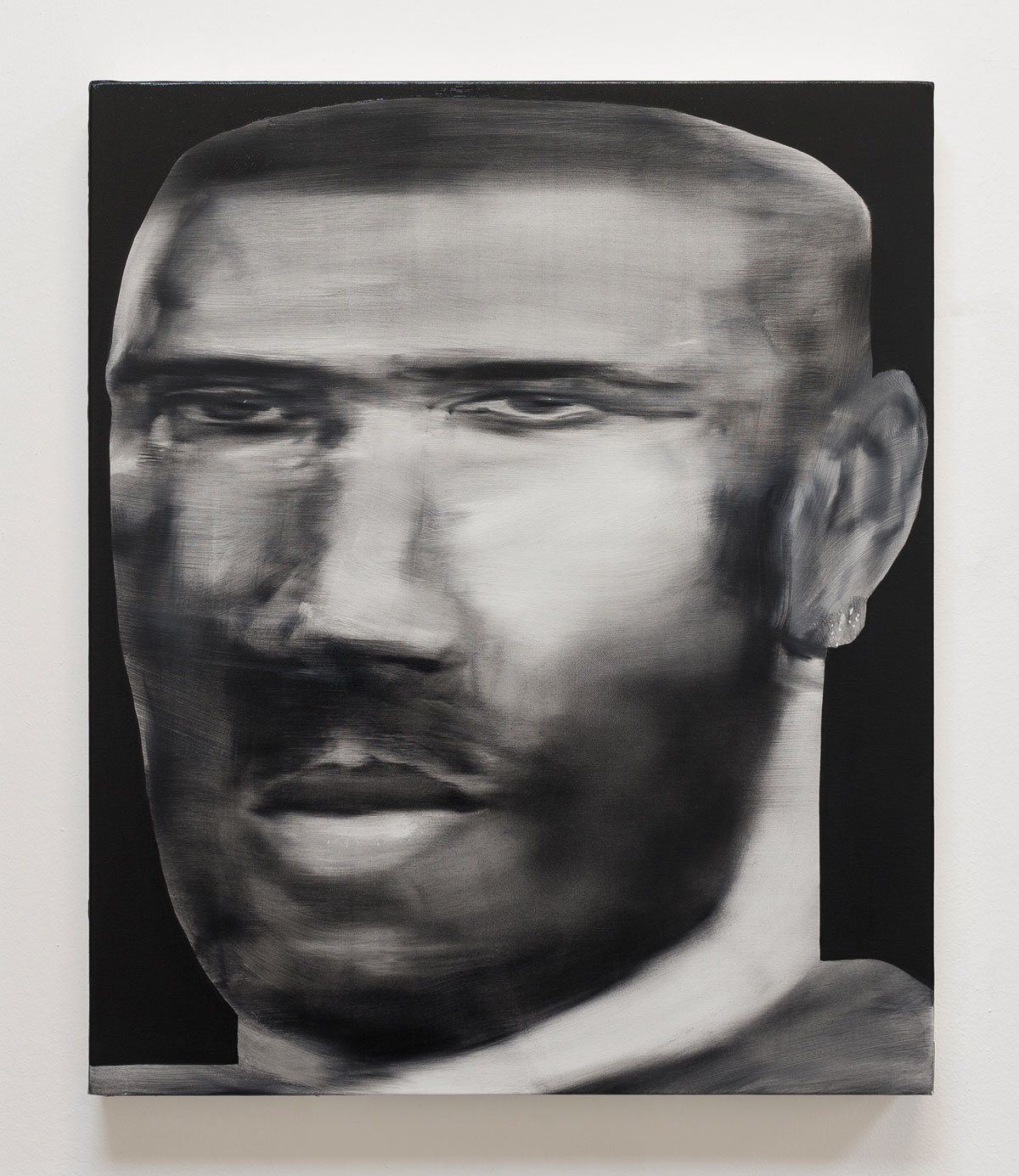

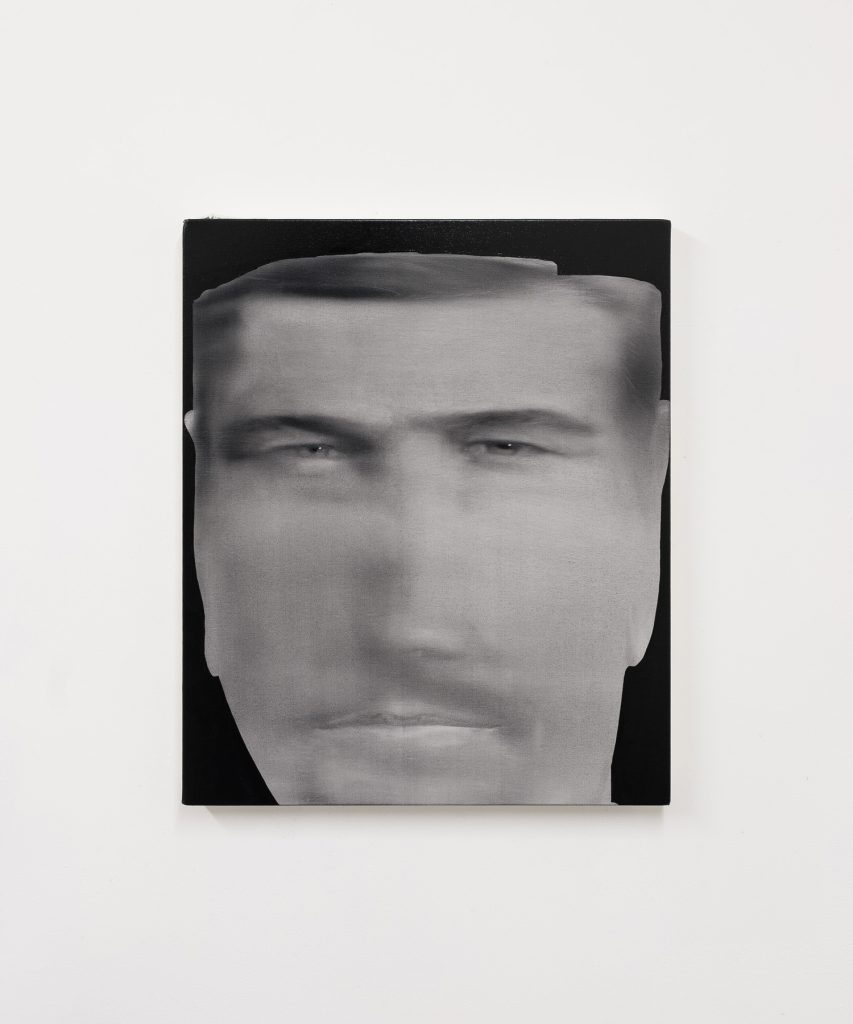

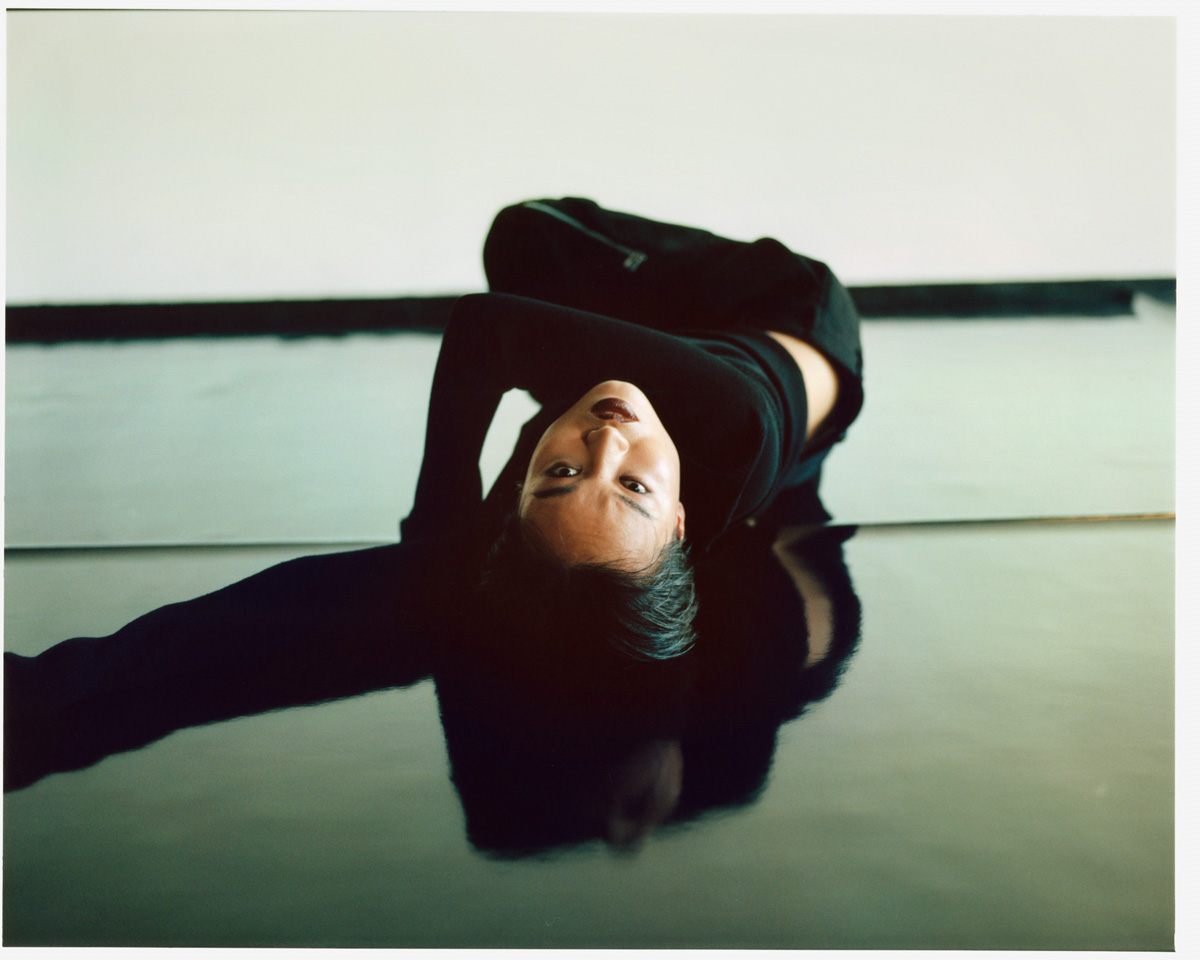

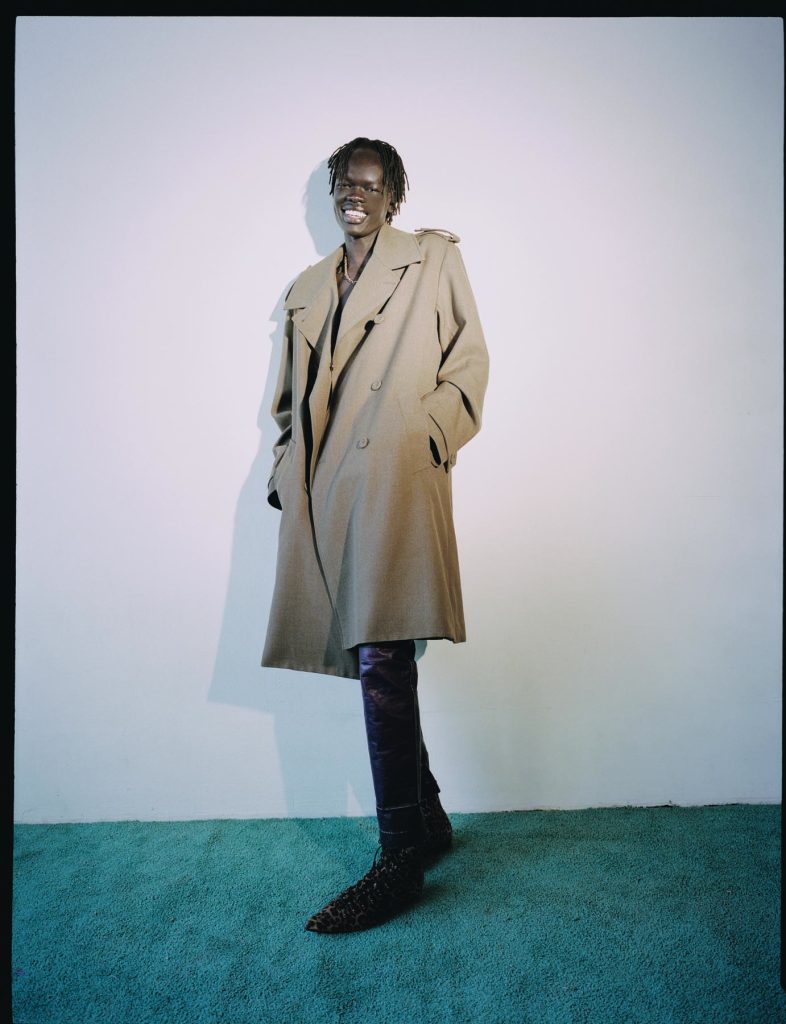

My latest projects cannot be really examined separately. They all share a similar spirit, a similar beginning, and a similar aim. My aim is always to heal my spectators’ precoded opinion and/or thinking which is given by their experience.

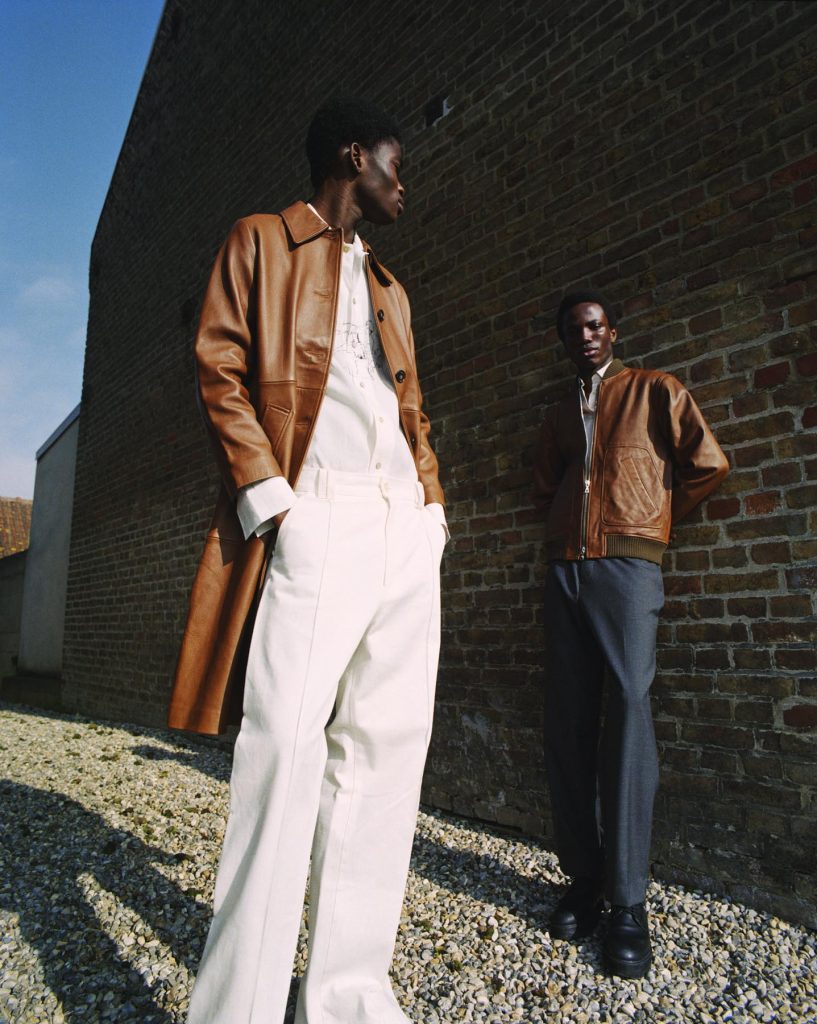

My ‘Karton’ furniture evokes a non-useable feeling, a forgotten childish dream. ‘Profil’ sculptures give spectators a distinctive look of regular fabrics hanging from the ceiling. My ‘Juxtaposition’ piece revokes a human act of protecting objects for their longevity.

All of these do not appear to be what they look like at first glance. I always encourage the spectators to interact with my work.

“I believe that only through the physical dialogue can my work achieve an ending. The idea is bigger than the outcome.”

In line with our theme Celebration, how do you celebrate yourself as an artist, a designer, and a creative? What joys outside your work do you live up?

To be honest, it feels very difficult to acknowledge the point where one can put a checkmark on the work. The work is always in the process. However, I am trying to learn to celebrate every day. The sum of the process is the outcome of the work. Living in the present can help one to realize happiness.

Is there anything that we should look forward to from you in the upcoming months?

At this time of answering the questions, I am in Los Angeles. In April, I will participate in a large group show at Side Gallery where I am excited to show my ‘Karton’ furniture series.

When I think further from here, I do not know what is coming next. Probably this is being in the now?

Credits

Images · Illya Goldman Gubin

https://www.igg-atelier.de/